Deck 14: Competing on Marketing and Supply Chain Management

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/23

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 14: Competing on Marketing and Supply Chain Management

1

In supply chain management, what are the differences between agility and adaptability?

Agility refers to ability of a firm to react to expect shifts in demand and supply as today things are very uncertain thus it becomes very important that supply chains should have agility. Companies now a day uses just in time and lean approaches which requires agile supply chain. To manage this various firms use trucks, ships and planes of the suppliers and carriers like warehouses.

In uncertain conditions an agile supply chain can rise to the challenge while a static one pulls a firm down. Agility focuses on being flexible to overcome short term fluctuation in supply chain.

Adaptability refers to ability of an organization to change supply chain configuration in response to long term changes in environment and technology. It is associated with decisions on whether to produce in house or to outsource. It requires a continuous monitoring of geopolitical, social and technological trends and accordingly reconfiguring the supply chain. It has long term impact.

In uncertain conditions an agile supply chain can rise to the challenge while a static one pulls a firm down. Agility focuses on being flexible to overcome short term fluctuation in supply chain.

Adaptability refers to ability of an organization to change supply chain configuration in response to long term changes in environment and technology. It is associated with decisions on whether to produce in house or to outsource. It requires a continuous monitoring of geopolitical, social and technological trends and accordingly reconfiguring the supply chain. It has long term impact.

2

Pumping out fancy clothing, handbags, jewelry, perfumes, and watches, the luxury goods industry had a challenging time in the Great Recession. In 2008, banks were falling left and right, unemployment rates were sky high, and consumer confidence was at an all time low. In 2009, total luxury goods industry sales fell by 20% globally. How did the industry cope? Marketing to Chinese emerged as one of the leading coping strategies for the luxury goods industry. Since 2008, Chinese consumption (both at home and traveling) had been growing between 20% and 30% annually. In 2009, China surpassed the United States to become the world's second largest market. In 2011, China rocketed ahead of Japan for the first time as the world's champion consumer of luxury goods- splashing $12.6 billion to command a 28% global market share. Everybody who was somebody in luxury goods had been elbowing their way into China, which appears like the New World to old European brands.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

Using the four Ps of marketing, explain how luxury goods makers can enhance their effectiveness in marketing to Chinese consumers.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

Using the four Ps of marketing, explain how luxury goods makers can enhance their effectiveness in marketing to Chinese consumers.

Effective marketing of the business depends on how you position it to satisfy your market's needs. The four Ps are the critical element in marketing product and services.

Product: focus of the organization should be on creating the right product which can satisfy the needs of your target customer. In this focus should not be only on physical product itself rather other elements like packaging, quality, features, options, service, warranties and brand name. Luxury goods should be focused on creating the right image for the consumers who have everything.

Price refers to how much will be charged for the product or service you offer. Organizations should use the price which could reflect the appropriate positioning of your product in the market and should also include the cost of item along with a profit margin. Luxury goods should not be priced at a lower cost as that signify the product to be of low quality and also the consumers who buy luxury goods are willing to pay a premium for the brand.

Place refers to the distribution channel which the organization will use to make the product available to consumer. How the product is distributed has a great impact on what your product is thus the luxury goods should use exclusive distributors for their products which will also ensure the genuineness of the product.

Promotion refers to what means the organization will use to make consumers aware of their products. Various channels like radio, print, electronic media, word of mouth, personal selling etc can be used for promotion of the product. Luxury goods should be promoted using advertisements which will create an impact on target consumers and should convey the message pride of possession.

Product: focus of the organization should be on creating the right product which can satisfy the needs of your target customer. In this focus should not be only on physical product itself rather other elements like packaging, quality, features, options, service, warranties and brand name. Luxury goods should be focused on creating the right image for the consumers who have everything.

Price refers to how much will be charged for the product or service you offer. Organizations should use the price which could reflect the appropriate positioning of your product in the market and should also include the cost of item along with a profit margin. Luxury goods should not be priced at a lower cost as that signify the product to be of low quality and also the consumers who buy luxury goods are willing to pay a premium for the brand.

Place refers to the distribution channel which the organization will use to make the product available to consumer. How the product is distributed has a great impact on what your product is thus the luxury goods should use exclusive distributors for their products which will also ensure the genuineness of the product.

Promotion refers to what means the organization will use to make consumers aware of their products. Various channels like radio, print, electronic media, word of mouth, personal selling etc can be used for promotion of the product. Luxury goods should be promoted using advertisements which will create an impact on target consumers and should convey the message pride of possession.

3

In aligning the interests of various players in the supply chain, what is the role of power and trust?

Alignment is the integration of interest of various players involved in the supply chain. Each of the players involved is a profit maximizing stand alone firm and thus conflicts arise. To achieve alignment the two key elements are power and trust.

In a supply chain each player has different levels of power and accordingly exercises bargaining power. A more powerful player in supply chain will exercise greater bargaining power for e.g. DB in diamonds facilitates legitimacy and efficiency of whole supply chain. Trust arises from perceived fairness and justice from all players of supply chain. Modern approaches like JIT or low inventory and more geographic dispersion of production has also created a need for all the players to invest in trust building mechanism so as to foster more collaboration.

Both power and trust are vital in alignment of interest of various players in supply chain for e.g. if there will be no particular player having more power in supply chain the result will be excessive bargaining among various players of equal or more standing. Thus power creates efficiency in whole supply chain similarly trust creates collaboration which is necessary for alignment of supply chain.

In a supply chain each player has different levels of power and accordingly exercises bargaining power. A more powerful player in supply chain will exercise greater bargaining power for e.g. DB in diamonds facilitates legitimacy and efficiency of whole supply chain. Trust arises from perceived fairness and justice from all players of supply chain. Modern approaches like JIT or low inventory and more geographic dispersion of production has also created a need for all the players to invest in trust building mechanism so as to foster more collaboration.

Both power and trust are vital in alignment of interest of various players in supply chain for e.g. if there will be no particular player having more power in supply chain the result will be excessive bargaining among various players of equal or more standing. Thus power creates efficiency in whole supply chain similarly trust creates collaboration which is necessary for alignment of supply chain.

4

ON CULTURE: Canada has an official animal: the beaver. In 2007, the Canadian prime minister suggested replacing it with the wolverine, and stirred up a national debate. Does your country have an official animal? If you were hired as a marketing expert by the government of Canada (or of whatever country), how would you best market the country using an animal?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

What are examples of how formal institutions affect marketing and supply chain management-i.e., examples of government-imposed rules of the game?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

Your company has developed a dominant global supply network that has contact with nearly every country in the world. However, recent internal initiatives have encouraged managers to reconfigure your company's supply network to increase efficiency. As a part of this process, you must use established logistics performance metrics to identify the country that has the highest logistics competence on each continent (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America). Prepare a report that indicates your recommendations and rationale for each continent. What can explain the results of your analysis?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

How is the issue of the "value" of some traditional marketing resources being affected by changes in technology?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

ON CULTURE: What cultural issue could be involved product decisions in terms of localization versus standardization?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

In your opinion, are manufacturing and service separate issues, and can one of the two be considered more important than the other? Explain.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Pumping out fancy clothing, handbags, jewelry, perfumes, and watches, the luxury goods industry had a challenging time in the Great Recession. In 2008, banks were falling left and right, unemployment rates were sky high, and consumer confidence was at an all time low. In 2009, total luxury goods industry sales fell by 20% globally. How did the industry cope? Marketing to Chinese emerged as one of the leading coping strategies for the luxury goods industry. Since 2008, Chinese consumption (both at home and traveling) had been growing between 20% and 30% annually. In 2009, China surpassed the United States to become the world's second largest market. In 2011, China rocketed ahead of Japan for the first time as the world's champion consumer of luxury goods- splashing $12.6 billion to command a 28% global market share. Everybody who was somebody in luxury goods had been elbowing their way into China, which appears like the New World to old European brands.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

From an institution-based view, explain why Chinese luxury goods consumers emerged to become a major group of consumers of such fancy items.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

From an institution-based view, explain why Chinese luxury goods consumers emerged to become a major group of consumers of such fancy items.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

What is the difference between market orientation and relationship orientation?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

ON ETHICS: In Hollywood movies, it is common to have product placement (having products from sponsored companies, such as cars, appear in movies without telling viewers that these are commercials). As a marketer, you are concerned about the ethical implications of product placement via Hollywood, yet you know the effectiveness of traditional advertising is declining. How do you proceed?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Select one of the four Ps, and make the case that it is more important than the other three. Then make the case that all are equally important.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

You are conducting an international survey concerning possible acceptance of a new leisure activity: space tourism. One issue that can influence whether individuals in a country find this new concept interesting is culture. Based on a data source that assesses culture around the world, identify the cultural trait that could measure general acceptance of space tourism by country. Then, determine which countries are ideal to target for commercialization. Be sure to support your position thoroughly in the report provided.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

Select one of the Triple As, and make the case that it is more important than the other two. Then make the case that all are equally important.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

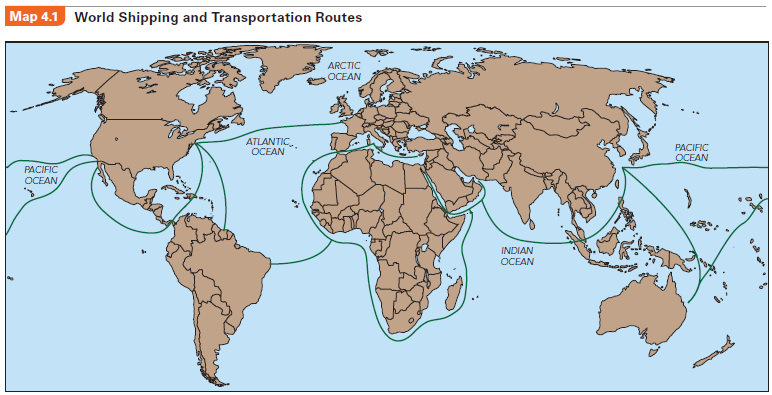

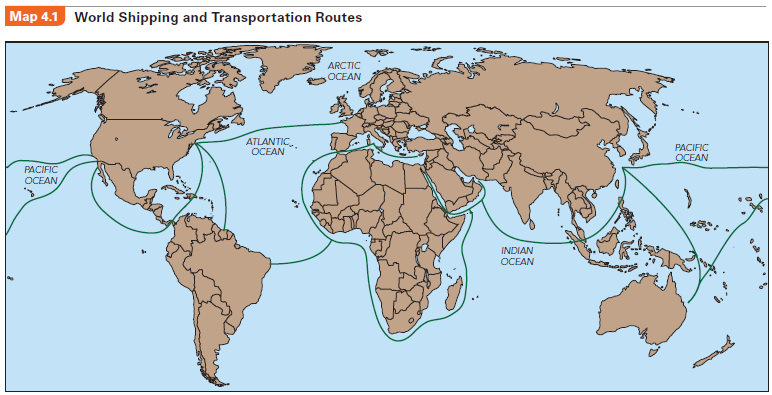

Refer to PengAtlas Map 4.1 (World Shipping and Transportation Routes). If global warming persists, how would it affect shipping and transportation routes? You can probably list some of the dangers of global warming but how may it actually benefit the economies of some countries or regions?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

Pumping out fancy clothing, handbags, jewelry, perfumes, and watches, the luxury goods industry had a challenging time in the Great Recession. In 2008, banks were falling left and right, unemployment rates were sky high, and consumer confidence was at an all time low. In 2009, total luxury goods industry sales fell by 20% globally. How did the industry cope? Marketing to Chinese emerged as one of the leading coping strategies for the luxury goods industry. Since 2008, Chinese consumption (both at home and traveling) had been growing between 20% and 30% annually. In 2009, China surpassed the United States to become the world's second largest market. In 2011, China rocketed ahead of Japan for the first time as the world's champion consumer of luxury goods- splashing $12.6 billion to command a 28% global market share. Everybody who was somebody in luxury goods had been elbowing their way into China, which appears like the New World to old European brands.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

From a VRIO standpoint, explain how luxury goods makers were able to capture the hearts, minds, and wallets of Chinese consumers.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

From a VRIO standpoint, explain how luxury goods makers were able to capture the hearts, minds, and wallets of Chinese consumers.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

ON ETHICS: You are a supply chain manager at a UK firm. In 2009, the H1N1 swine flu broke out in Mexico and the United States, potentially affecting your suppliers in the region. On the one hand, you are considering switching to a new supplier in Central Europe. On the other hand, you feel bad about abandoning your Mexican and US suppliers, with whom you have built a pleasant personal and business relationship, at this difficult moment. Yet, your tightly coordinated production cannot afford to miss one supply shipment. How do you proceed?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

Refer to PengAtlas Map 4.3 (World Labor Force) and to Maps 2.1 and 2.2 (Top Exporters and Importers). To what extent is the size of the labor force an indicator of the size of markets, and to what extent is it not? Why?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

20

Pumping out fancy clothing, handbags, jewelry, perfumes, and watches, the luxury goods industry had a challenging time in the Great Recession. In 2008, banks were falling left and right, unemployment rates were sky high, and consumer confidence was at an all time low. In 2009, total luxury goods industry sales fell by 20% globally. How did the industry cope? Marketing to Chinese emerged as one of the leading coping strategies for the luxury goods industry. Since 2008, Chinese consumption (both at home and traveling) had been growing between 20% and 30% annually. In 2009, China surpassed the United States to become the world's second largest market. In 2011, China rocketed ahead of Japan for the first time as the world's champion consumer of luxury goods- splashing $12.6 billion to command a 28% global market share. Everybody who was somebody in luxury goods had been elbowing their way into China, which appears like the New World to old European brands.

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

ON ETHICS: If you were CEO of a Western luxury goods firm, how would you respond to a Chinese reporter who asked you to comment on the two main criticisms of luxury goods consumption in China?

The luxury goods industry was dominated by the Big Three: LVMH (with more than 50 brands, such as Louis Vuitton handbags, Moët Hennessy liquor, Christian Dior cosmetics, TAG Heuer watches, and Bulgari jewlery), Gucci Group (with nine brands such as Gucci handbags, Yves Saint Laurent clothing, and Sergio Rossi shoes), and Burberry (famous for raincoats and handbags). Next were a number of more specialized players, such as king of menswear Ermenegildo Zegna. By definition, high fashion means high prices.

Before Chinese consumers became a force to be reckoned with, the luxury goods industry had long endeavored to manage the fickle and capricious customers. Although the seriously rich were not affected by the Great Recession, their number remained small. Most luxury goods firms had been relying on the "aspirational" customers to fund their growth. As the recession became worse, many middle-class customers in economically depressed, developed economies began to hunt for value instead of triviality and showing off. Japan had been the number-one market for luxury goods for years, and most Japanese women reportedly owned at least one Louis Vuitton product. But sales were falling since 2005, and dropped sharply since 2008. Young Japanese women seemed more individualistic than their mothers, and often hauled home lesser-known (and cheaper) brands.

As Chinese consumers charged ahead, their consumption patterns quickly revealed some interesting surprises. First, Chinese purchased more luxury goods outside of China, often on vacations abroad, than in China. Although practically all luxury goods producers now had opened retail outlets in major Chinese cities, they suffered from high prices-thanks to import duties. Retail outlets in China also suffered from the perception (although never proven) that some counterfeit products might slip into their supply chain. Because luxury products purchased abroad were less likely to be fakes, many Chinese vacationers in Europe were actually shoppers. They also enjoyed the lower prices abroad. Instead of buying one or two pieces, some Chinese shoppers bought five Rolex watches or ten Louis Vuitton bags on one trip. To cater to such demand, almost all luxury shop operators in Europe now employed some Chinese-speaking staff. Many China-based travel agencies organized "European vacation" itineraries with only two hours in the Louvre or the British Museum but six hours in Paris' Galeries Lafayette or London's Harrods.

Second, both inside and outside of China, Chinese shoppers discriminated against made-in-China luxury goods, which were viewed as inferior in quality. Since a luxury item should carry all the mystique associated with a high-prestige country, many Chinese consumers argued, why bother to spend that much money to buy something made in China (never mind the bonafide Western luxury brands of these products)?

Third, interestingly, several years ago, it was the Japanese ladies who did the heavy lifting for the top line of luxury goods firms. Now it is the Chinese dudes (more likely than the Chinese women) who were eager to open their wallets to indulge themselves with luxurious trappings. As a result, menswear brands such as Ermenegildo Zegna and Dunhill did very well.

Such conspicuous consumption generated hot debates in China. It attracted two criticisms. First, luxury goods were some of the most visible signs of rising income inequality. Second, luxury goods and corruption were allegedly twins. Not every luxury item bought from Galeries Lafayette or Harrods was for the personal consumption of the purchaser and his or her family members. An untold number was reportedly used as bribes. Therefore, critics argued that luxury goods fostered corruption.

For all their proclaimed interest in corporate social responsibility, no luxury goods firm bothered to confront the Chinese debates concerning the ethical responsibility of their products. However, the industry was concerned about the sustainability of current growth. Over time, as the pent-up demand for the first generation of Chinese who were wealthy enough to travel abroad and buy luxury goods gradually recedes, such a shopping pattern (buying five to ten pieces of luxury item on one trip abroad) may not repeat itself. But then, given the population base, a lot more Chinese consumers from second- and thirdtier cities may want to imitate what their fellow countrymen and countrywomen in first-tier cities did by indulging themselves with such products. So, there is still plenty of room for growth in China. Of course, the luxury goods industry was also eagerly chasing consumers in other emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, Poland, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Where did LVMH open one of its newest stores? Ulan Bator, Mongolia.

Case Discussion Questions :

ON ETHICS: If you were CEO of a Western luxury goods firm, how would you respond to a Chinese reporter who asked you to comment on the two main criticisms of luxury goods consumption in China?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

21

If marketing efforts could help produce an inelastic demand for a product, a firm would have much more upward pricing flexibility. Explain why that is true.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

22

Which of the four P's has come to be known by a new term? Why the change?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

23

What marketing risks are associated with outsourcing? How would you minimize those risks?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 23 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck