Deck 1: Ethics Environment : Ethics Expectations

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/62

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 1: Ethics Environment : Ethics Expectations

1

Why are philosophical approaches to ethical decision making relevant to modern corporations and professional accountants?

According to the text, the philosophical approaches to ethical decision making for corporations and accountants are:

• Consequentialism : Consequentialism requires that ethical decisions have good consequences.

• Deontology : Deontology holds that an ethical act depends upon the duty, rights and justice involved.

• Virtue Ethics : Under virtue ethics, an act is considered ethical if it demonstrates the virtues expected by stakeholders of the participants.

These philosophical approaches are becoming more and more relevant because of the growing awareness, interest and power of stakeholders in building and maintaining a company's reputation (and success).

• Consequentialism : Consequentialism requires that ethical decisions have good consequences.

• Deontology : Deontology holds that an ethical act depends upon the duty, rights and justice involved.

• Virtue Ethics : Under virtue ethics, an act is considered ethical if it demonstrates the virtues expected by stakeholders of the participants.

These philosophical approaches are becoming more and more relevant because of the growing awareness, interest and power of stakeholders in building and maintaining a company's reputation (and success).

2

In 1964, at the invitation of the Ecuadorian government, Texaco Inc. began operations through a subsidiary, TexPet, in the Amazon region of Ecuador. The purpose of the project was to "develop Ecuador's natural resources and encourage the colonization of the area." TexPet was a minority owner of the project and its partner was Petroecuador, the government-owned oil company. Over the years from 1968 to 1992, the consortium extracted 1.4 billion barrels of oil from the Ecuadorian operations. Ecuador benefited greatly during this period. Ecuador received approximately 98 percent of all moneys generated by the consortium in the form of royalties, taxes, and revenues. Altogether, this amount represented more than 50 percent of Ecuador's gross national product during that period. TexPet's operations over the years provided jobs for 840 employees and approximately 2,000 contract workers, thereby benefiting almost 3,000 Ecuadorian families directly, in addition to the thousands of Ecuadorian nationals who supplied the company's needs for goods and services. Also, TexPet made substantial contributions to the Quito, Guayaquil, and Loja Polytechnics and other institutions of higher education. Oil is Ecuador's life-blood-a $1 billion per year industry that accounts for 50 percent of the export earnings and 62 percent of its fiscal budget. Unfortunately, problems also arose. Although Petroecuador acquired 100 percent of the ownership of the Transecuadorian pipeline in 1986, TexPet still accounted for 88 percent of all oil production and operated the pipeline in 1987 when it ruptured and was buried by a landslide. A spill of 16.8 million gallons (4.4 million barrels) occurred, which Texaco attributed to a major earthquake that devastated Ecuador. Other spills apparently occurred as well. Although Texaco pulled out of the consortium in 1992 entirely (having retreated to be a silent minority partner in 1990), three lawsuits were filed against it in the United States-the Aquinda (November 1993), the Sequihua (August 1993), and the Jota (1994). The indigenous people who launched the lawsuits charged that, during two decades of oil drilling in the Amazon, Texaco dumped more than 3,000 gallons of crude oil a day-millions of gallons in total-into the environment. The indigenous people say their rivers, streams, and lakes are now contaminated, and the fish and wild game that once made up their food supply are now decimated. They asked in the lawsuit that Texaco compensate them and clean up their land and waters. Maria Aquinda, for whom the suit is named, says that contaminated water from nearby oil wells drilled by the Texaco subsidiary caused her to suffer chronic stomach ailments and rashes and that she lost scores of pigs and chickens. Aquinda and 76 other Amazonian residents filed a $1.5 billion lawsuit in New York against Texaco. The class-action suit, representing 30,000 people, further alleges that Texaco acted "with callous disregard for the health, wellbeing, and safety of the plaintiffs" and that "large-scale disposal of inadequately treated hazardous wastes and destruction of tropical rain forest habitats, caused harm to indigenous peoples and their property." According to the Ecuadorian environmental group Ecological Action, Texaco destroyed more than 1 million hectares of tropical forest, spilled 74 million liters of oil, and used obsolete technology that led to the dumping of 18 million liters of toxic waste. Rainforest Action Network, a San Francisco-based organization, says effects include poor crop production in the affected areas, invasion of tribal lands, sexual assaults committed by oil workers, and loss of game animals (which would be food supply for the indigenous peoples). Audits were conducted to address the impact of operations on the soil, water, and air and to assess compliance with environmental laws, regulations, and generally accepted operating practices. Two internationally recognized and independent consulting firms, AGRA Earth Environmental Ltd. and Fugro- McClelland, conducted audits in Ecuador. Each independently concluded that TexPet acted responsibly and that no lasting or significant environmental impact exists from its former operations. Nonetheless, TexPet agreed to remedy the limited and localized impacts attributable to its operations. On May 4, 1995, Ecuador's minister of energy and mines, the president of Petroecuador, and TexPet signed the Contract for Implementing of Environmental Remedial Work and Release from Obligations, Liability, and Claims following negotiations with Ecuadorian government officials representing the interests of indigenous groups in the Amazon. In this remediation effort, producing wells and pits formerly utilized by TexPet were closed, producing water systems were modified, cleared lands were replanted, and contaminated soil was remediated. All actions taken were inspected and certified by the Ecuadorian government. Additionally, TexPet funded social and health programs throughout the region of operations, such as medical dispensaries and sewage and potable water systems. That contract settled all claims by Petroecuador and the Republic of Ecuador against TexPet, Texaco, and their affiliates for all matters arising out of the consortium's operations. In the summer of 1998, the $40 million remediation project was completed. On September 30, 1998, Ecuador's minister of energy and mines, the president of Petroecuador, and the general manager of Petropro-duccion signed the Final Release of Claims and Delivery of Equipment. This document finalized the government of Ecuador's approval of TexPet's environmental remediation work and further stated that TexPet fully complied with all obligations established in the remediation agreement signed in 1995. Meanwhile, in the United States, Texaco made the following arguments against the three lawsuits:

• Activities were in compliance with Ecuadorian laws, and international oil industry standards.

• Activities were undertaken by a largely Ecuadorian workforce-which Texaco believed would always act in the interest of its community/country.

• All investments/operations were approved and monitored by the Ecuadorian government and Petroecuador.

• All activities were conducted with the oversight and approval of the Ecuadorian government.

• Environmentally friendly measures were used, such as helicopters instead of roads.

• The health of Ecuadorians increased during the years Texaco was in Ecuador. • Ninety-eight percent of the money generated stayed in Ecuador-50 percent of GDP during that period.

• Jobs were provided for 2,800.

• Money was provided for schools.

• Independent engineering firms found no lasting damage.

• A $40 million remediation program was started per an agreement with the Ecuadorian government.

• U.S. courts should not govern activities in a foreign country.

The three lawsuits were dismissed for similar reasons-the Sequihua in 1994, the Aquinda in 1996, and the Jota in 1997. The Aquinda lawsuit, for example, was launched in New York (where Texaco has its corporate headquarters) because Texaco no longer had business in Ecuador and could not be sued there. The case was dismissed by a New York court in November 1996 on the basis that it should be heard in Ecuador. Failing that, the Ecuadorian government should have been involved in the case as well, or that the case should have been filed against the government and the state-owned Petroecuador as well as Texaco. At that point, the Ecuadorian government did get involved and filed an appeal of the decision. This was the first time a foreign government had sued a U.S. oil company in the United States for environmental damage. In addition, in 1997, the plaintiffs in the Aquinda and Jota cases also appealed the district court's decisions.

On October 5, 1998, a U.S. court of appeals remanded both cases to the district court for further consideration as to whether they should proceed in Ecuador or the United States. Written submissions were filed on February 1, 1999. Texaco has long argued that the appropriate venue for these cases is Ecuador because the oilproducing operations took place in Ecuador under the control and supervision of Ecuador's government, and the Ecuadorian courts have heard similar cases against other companies. It is Texaco's position that U.S. courts should not govern the activities of a sovereign foreign nation, just as foreign courts should not govern the activities of the United States. In fact, Texaco claimed the ambassador of Ecuador, the official representative of the government of Ecuador, noted in a letter to the district court that Ecuador would not waive its sovereign immunity.

Notwithstanding Texaco's arguments, the case was sent back to the court that threw it out, on the basis that the government of Ecuador does have the right to intervene. The question of whether the case can and will finally be tried in the United States or Ecuador under these circumstances will now take many years to be decided. Texaco claims that it has done enough to repair any damage and disputes the scientific validity of the claims-the Amazonians (or their supporters) seem to have the resources to continue fighting this suit in the U.S. courts. Ultimately the company may prefer the fairness of U.S. courts.

Questions

Should Ecuadorians be able to sue Texaco in U.S. courts?

• Activities were in compliance with Ecuadorian laws, and international oil industry standards.

• Activities were undertaken by a largely Ecuadorian workforce-which Texaco believed would always act in the interest of its community/country.

• All investments/operations were approved and monitored by the Ecuadorian government and Petroecuador.

• All activities were conducted with the oversight and approval of the Ecuadorian government.

• Environmentally friendly measures were used, such as helicopters instead of roads.

• The health of Ecuadorians increased during the years Texaco was in Ecuador. • Ninety-eight percent of the money generated stayed in Ecuador-50 percent of GDP during that period.

• Jobs were provided for 2,800.

• Money was provided for schools.

• Independent engineering firms found no lasting damage.

• A $40 million remediation program was started per an agreement with the Ecuadorian government.

• U.S. courts should not govern activities in a foreign country.

The three lawsuits were dismissed for similar reasons-the Sequihua in 1994, the Aquinda in 1996, and the Jota in 1997. The Aquinda lawsuit, for example, was launched in New York (where Texaco has its corporate headquarters) because Texaco no longer had business in Ecuador and could not be sued there. The case was dismissed by a New York court in November 1996 on the basis that it should be heard in Ecuador. Failing that, the Ecuadorian government should have been involved in the case as well, or that the case should have been filed against the government and the state-owned Petroecuador as well as Texaco. At that point, the Ecuadorian government did get involved and filed an appeal of the decision. This was the first time a foreign government had sued a U.S. oil company in the United States for environmental damage. In addition, in 1997, the plaintiffs in the Aquinda and Jota cases also appealed the district court's decisions.

On October 5, 1998, a U.S. court of appeals remanded both cases to the district court for further consideration as to whether they should proceed in Ecuador or the United States. Written submissions were filed on February 1, 1999. Texaco has long argued that the appropriate venue for these cases is Ecuador because the oilproducing operations took place in Ecuador under the control and supervision of Ecuador's government, and the Ecuadorian courts have heard similar cases against other companies. It is Texaco's position that U.S. courts should not govern the activities of a sovereign foreign nation, just as foreign courts should not govern the activities of the United States. In fact, Texaco claimed the ambassador of Ecuador, the official representative of the government of Ecuador, noted in a letter to the district court that Ecuador would not waive its sovereign immunity.

Notwithstanding Texaco's arguments, the case was sent back to the court that threw it out, on the basis that the government of Ecuador does have the right to intervene. The question of whether the case can and will finally be tried in the United States or Ecuador under these circumstances will now take many years to be decided. Texaco claims that it has done enough to repair any damage and disputes the scientific validity of the claims-the Amazonians (or their supporters) seem to have the resources to continue fighting this suit in the U.S. courts. Ultimately the company may prefer the fairness of U.S. courts.

Questions

Should Ecuadorians be able to sue Texaco in U.S. courts?

Yes, Ecuadorians should have the right to sue Texaco in U.S. courts based on Texaco's actions in Ecuador.

Texaco is a U.S. based corporation and therefore, is subject to U.S. laws and standards regarding its actions. Consider, for example, if those affected by BP's Gulf of Mexico oil spill could not seek reparations in the U.K. courts, if they were not subject to remedies under U.S. law?

If companies knew that they were only liable for behavior based on local country legal, moral and ethical standards, they would have little or no incentive to act ethically when their assets were located on foreign soil.

Texaco is a U.S. based corporation and therefore, is subject to U.S. laws and standards regarding its actions. Consider, for example, if those affected by BP's Gulf of Mexico oil spill could not seek reparations in the U.K. courts, if they were not subject to remedies under U.S. law?

If companies knew that they were only liable for behavior based on local country legal, moral and ethical standards, they would have little or no incentive to act ethically when their assets were located on foreign soil.

3

On July 16, 2008, it was announced that several Chinese producers of baby milk powder had been adding melamine, a chemical usually used in countertops, to increase the "richness" of their milk powder and to increase the protein count. Shockingly, the melaminetainted milk powder was responsible for the deaths of four infants and the sickening of more than 6,200 more. Milk manufacturers had been using melamine as a low-cost way of "enriching" their product in both taste and protein count.

Melamine, a toxic chemical that makes countertops very durable, damages kidneys. This fact came to world attention on March 16, 2007, when Menu Foods of Streetsville, Ontario, Canada, recalled dog and cat foods that it had mixed in Canada from Chinese ingredients that were found to include melamine. Very quickly thereafter, pet owners claims and class action lawsuits threatened to put the company into bankruptcy until settlements were worked out. A subsequent investigation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) led to the recall of pet food by major manufacturers, including Del Monte, Nestle Purina, Menu Foods, and many others. On February 6, 2008, "the FDA announced that that two Chinese nationals and the businesses they operate, along with a U.S. company and its president and chief executive officer, were indicted by a federal grand jury for their roles in a scheme to import products purported to be wheat gluten into the United States that were contaminated with melamine." It will be interesting to follow what penalties are ultimately paid by the Chinese manufacturers.

Although the story of melamine-tainted ingredients broke in mid-March 2007, the similarly tainted-milk powder link did not come to light in China until sixteen months later. Governmental follow-up has not been speedy even though unmarked bags of "protein powder" had probably been added to several other products, including baking powder and feed for chickens thus contaminating eggs and meat. On October 8, 2008, the Chinese government stopped reporting updated figures of infant milk powder sufferers "because it is not an infectious disease, so it's not necessary to announce it to the public." Knowledgeable members of the Chinese public, however, have been using the suitcases of their visiting relatives to import U.S.- and Canadianmade milk formula for their children.

It is also fascinating to consider another aspect of life in China-rumored control of online news. Although there is no proof of the rumors, which might have been started by competitors, the Wall Street Journal's (WSJ) online service has reported that Baidu.com Inc., the company referred to as the "Google of China," is under attack for accepting payments to keep stories containing a specific milk manufacturing company's name from online searches about the tainted milk scandal even when the manufacturer was recalling the product. Local government officials also declined to confirm the milk manufacturer's problem during the same period.

Baidu.com "said it had been approached this week by several dairy producers but said that it 'flat out refused' to screen out unfavorable news and accused rivals of fanning the flames."9 In a statement, it said: "Baidu respects the truth, and our search results reflect that commitment."

Currently, there is no evidence that Baidu.com did accept the screen-out payments as rumored, but it does face some challenges of its own making in trying to restore it reputation. For example, unlike Google that separates or distinguishes paid advertisements from non-paid search results, Baidu.com integrated paid advertisements into its search listing until critics recently complained. In addition, companies could pay more and get a higher ranking for their ads. According to the WSJ article, a search for "mobile phone" generates a list where almost the entire first page consists of paid advertisements. Also, competitors fearing increased competition and new products from Baidu.com, which recently increased its market share to 64.4 percent, have begun to restrict Baidu's search software (spiders) from penetrating websites that the competitors control.

Baidu.com's profit growth had been strong, but for how long? Baidu.com, Inc. is traded on the U.S.'s NASDAQ Stock Market under the symbol BIDU. Since the rumors surfaced in late August/early September 2008, BIDU's share price has declined from $308 to almost $110 on November 20, 2008.

What steps could Baidu.com take to restore its reputation, and what challenges will it have to overcome?

Melamine, a toxic chemical that makes countertops very durable, damages kidneys. This fact came to world attention on March 16, 2007, when Menu Foods of Streetsville, Ontario, Canada, recalled dog and cat foods that it had mixed in Canada from Chinese ingredients that were found to include melamine. Very quickly thereafter, pet owners claims and class action lawsuits threatened to put the company into bankruptcy until settlements were worked out. A subsequent investigation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) led to the recall of pet food by major manufacturers, including Del Monte, Nestle Purina, Menu Foods, and many others. On February 6, 2008, "the FDA announced that that two Chinese nationals and the businesses they operate, along with a U.S. company and its president and chief executive officer, were indicted by a federal grand jury for their roles in a scheme to import products purported to be wheat gluten into the United States that were contaminated with melamine." It will be interesting to follow what penalties are ultimately paid by the Chinese manufacturers.

Although the story of melamine-tainted ingredients broke in mid-March 2007, the similarly tainted-milk powder link did not come to light in China until sixteen months later. Governmental follow-up has not been speedy even though unmarked bags of "protein powder" had probably been added to several other products, including baking powder and feed for chickens thus contaminating eggs and meat. On October 8, 2008, the Chinese government stopped reporting updated figures of infant milk powder sufferers "because it is not an infectious disease, so it's not necessary to announce it to the public." Knowledgeable members of the Chinese public, however, have been using the suitcases of their visiting relatives to import U.S.- and Canadianmade milk formula for their children.

It is also fascinating to consider another aspect of life in China-rumored control of online news. Although there is no proof of the rumors, which might have been started by competitors, the Wall Street Journal's (WSJ) online service has reported that Baidu.com Inc., the company referred to as the "Google of China," is under attack for accepting payments to keep stories containing a specific milk manufacturing company's name from online searches about the tainted milk scandal even when the manufacturer was recalling the product. Local government officials also declined to confirm the milk manufacturer's problem during the same period.

Baidu.com "said it had been approached this week by several dairy producers but said that it 'flat out refused' to screen out unfavorable news and accused rivals of fanning the flames."9 In a statement, it said: "Baidu respects the truth, and our search results reflect that commitment."

Currently, there is no evidence that Baidu.com did accept the screen-out payments as rumored, but it does face some challenges of its own making in trying to restore it reputation. For example, unlike Google that separates or distinguishes paid advertisements from non-paid search results, Baidu.com integrated paid advertisements into its search listing until critics recently complained. In addition, companies could pay more and get a higher ranking for their ads. According to the WSJ article, a search for "mobile phone" generates a list where almost the entire first page consists of paid advertisements. Also, competitors fearing increased competition and new products from Baidu.com, which recently increased its market share to 64.4 percent, have begun to restrict Baidu's search software (spiders) from penetrating websites that the competitors control.

Baidu.com's profit growth had been strong, but for how long? Baidu.com, Inc. is traded on the U.S.'s NASDAQ Stock Market under the symbol BIDU. Since the rumors surfaced in late August/early September 2008, BIDU's share price has declined from $308 to almost $110 on November 20, 2008.

What steps could Baidu.com take to restore its reputation, and what challenges will it have to overcome?

The text outlines several steps that Baidu.com can take to restore its reputation:

• Prove that it is not guilty of the allegations of "pay for promotion"

• Disclose that it is guilty and steps it has taken to ensure that a similar situation will not recur. These steps can include improved policy disclosure and perhaps outside monitoring.

• Seek to build a reputation as a "good corporate citizen" through marketing, charitable work and similar actions

Baidu.com will likely face several challenges in efforts to restore its reputation:

• Stakeholders, customers and others who have a "once burned, twice shy" philosophy of forgiving misdeeds.

• Overcoming rumors of past misdeeds - real or apparent.

• Overcoming any internal or competitive hurdles to full-transparency at the company. This step may be particularly challenging for a company operating in a country known for secretive tendencies.

• Prove that it is not guilty of the allegations of "pay for promotion"

• Disclose that it is guilty and steps it has taken to ensure that a similar situation will not recur. These steps can include improved policy disclosure and perhaps outside monitoring.

• Seek to build a reputation as a "good corporate citizen" through marketing, charitable work and similar actions

Baidu.com will likely face several challenges in efforts to restore its reputation:

• Stakeholders, customers and others who have a "once burned, twice shy" philosophy of forgiving misdeeds.

• Overcoming rumors of past misdeeds - real or apparent.

• Overcoming any internal or competitive hurdles to full-transparency at the company. This step may be particularly challenging for a company operating in a country known for secretive tendencies.

4

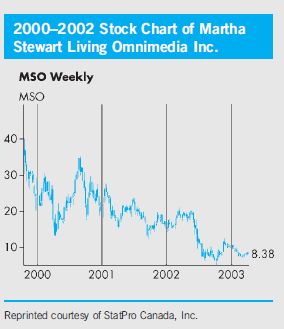

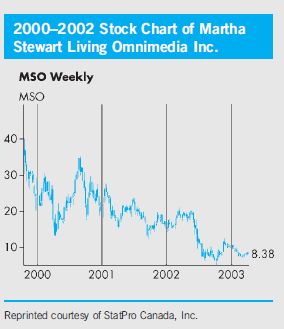

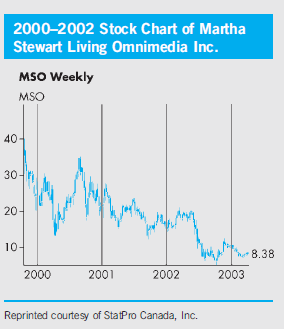

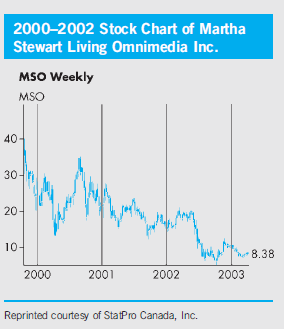

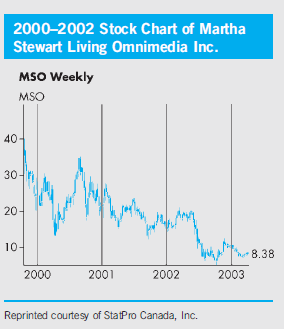

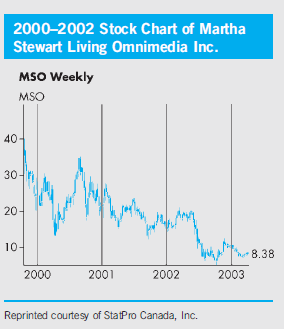

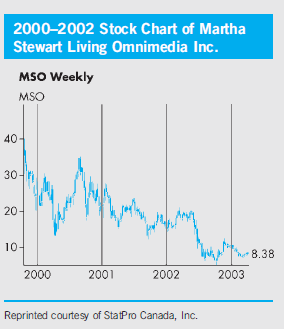

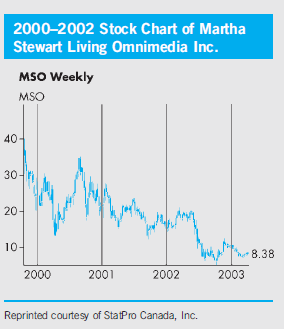

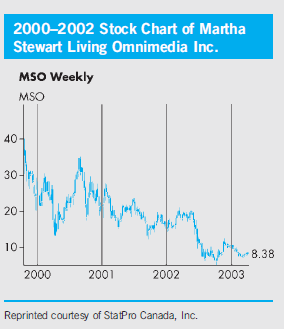

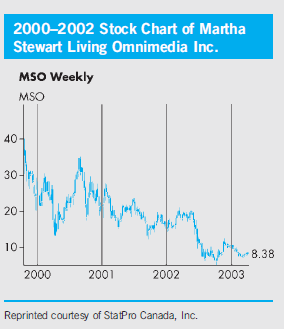

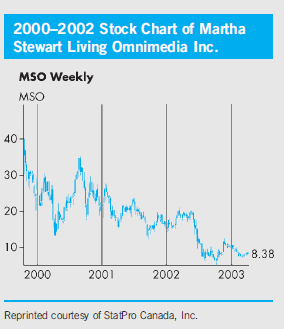

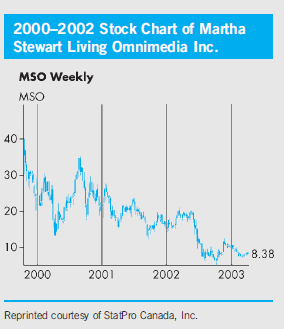

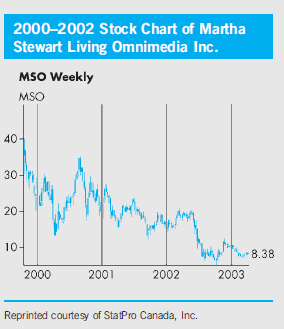

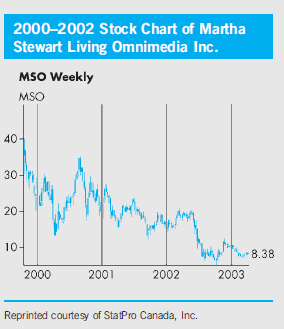

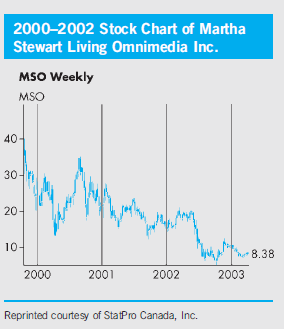

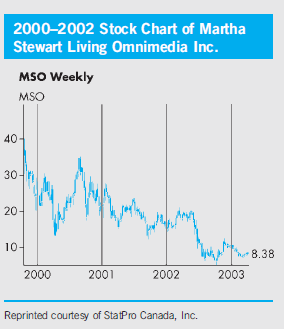

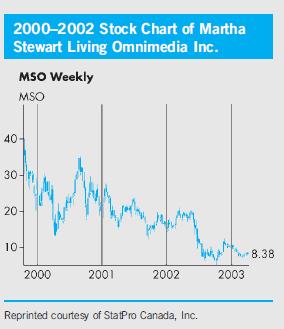

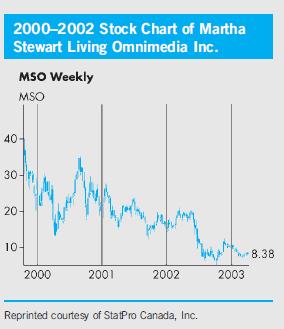

In June 2002, Martha Stewart began to wrestle with allegations that she had improperly used inside information to sell a stock investment to an unsuspecting investing public. That was when her personal friend Sam Waksal was defending himself against Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) allegations that he had tipped off his family members so they could sell their shares of ImClone Systems Inc. (ImClone) just before other investors learned that ImClone's fortunes were about to take a dive. Observers presumed that Martha was also tipped off and, even though she proclaimed her innocence, the rumors would not go away.

On TV daily as the reigning guru of homemaking, Martha is the multimillionaire proprietor, president, and driving force of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. (MSO), of which, on March 18, 2002, she owned 30,713,475 (62.6 percent) of the class A, and 30,619,375 (100 percent) of the class B shares. On December 27, 2001, Martha's class A and class B shares were worth approximately $17 each, so on paper Martha's MSO class A shares alone were worth over $500 million. Class B shares are convertible into class A shares on a oneto- one basis.

Martha's personal life became public. The world did not know that Martha Stewart had sold 3,928 shares of ImClone for $58 each on December 27, 2001,until it surfaced in June 2002. The sale generated only $227,824 for Martha, and she avoided losing $45,673 when the stock price dropped the next day, but it has caused her endless personal grief and humiliation, and the loss of reputation, as well as a significant drop to $5.26 in the MSO share price.

What Happened?

Martha had made an investment in ImClone, a company that was trying to get the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to bring to market an anti-colon cancer drug called Erbitux. Samuel Waksal, then the CEO of ImClone and a personal friend of Martha's, was apparently warned on or close to December 25, 2001, that the FDA was going to refuse5 to review Erbitux. According to SEC allegations, Sam relayed the information to his family so they could dump their ImClone shares on an unsuspecting public before the official announcement. Martha claims that she didn't get any inside information early from Sam, but regulators believe that she may have or from her broker or her broker's aide. The activities of several of Sam's friends, including Martha, are under investigation by the SEC.

Sam was arrested on June 12, 2002, and charged with "nine criminal counts of conspiracy, securities fraud and perjury, and then freed on $10 million bail." In a related civil complaint, the SEC alleged that Sam "tried to sell ImClone stock and tipped family members before ImClone's official FDA announcement on Dec. 28."

According to the SEC, two unidentified members of Sam's family sold about $10 million worth of ImClone stock in a twoday interval just before the announcement. Moreover, Sam also tried for two days to sell nearly 80,000 ImClone shares for about $5 million, but two different brokers refused to process the trades.

Martha has denied any wrongdoing. She was quoted as saying: "In placing my trade I had no improper information…. My transaction was entirely lawful." She admitted calling Sam after selling her shares, but claimed: "I did not reach Mr. Waksal, and he did not return my call." She maintained that she had an agreement with her broker to sell her remaining ImClone shares "if the stock dropped below $60 per share."

Martha's public, however, was skeptical. She was asked embarrassing questions when she appeared on TV for a cooking segment, and she declined to answer saying: "I am here to make my salad." Martha's interactions with her broker, Peter Bacanovic, and his assistant, Douglas Faneuil, are also being scrutinized. Merrill Lynch Co. suspended Bacanovic (who was also Sam Waksal's broker) and Faneuil, with pay, in late June. Later, since all phone calls to brokerages are taped and emails kept, it appeared to be damning when Bacanovic initially refused to provide his cell phone records to the House Energy and Commerce Commission for their investigation. Moreover, on October 4, 2001, Faneuil "pleaded guilty to a charge that he accepted gifts from his superior in return for keeping quiet about circumstances surrounding Stewart's controversial stock sale." Faneuil admitted that he received extra vacation time, including a free airline ticket from a Merrill Lynch employee in exchange for withholding information from SEC and FBI investigators.

According to the Washington Post report of Faneuil's appearance in court:

On the morning of Dec. 27, Faneuil received a telephone call from a Waksal family member who asked to sell 39,472 shares for almost $2.5 million, according to court records. Waksal's accountant also called Faneuil in an unsuccessful attempt to sell a large bloc of shares, the records show. Prosecutors allege that those orders "constituted material non-public information." But they alleged that Faneuil violated his duty to Merrill Lynch by calling a "tippee" to relate that Waksal family members were attempting to liquidate their holdings in ImClone. That person then sold "all the Tippee's shares of ImClone stock, approximately 3,928 shares, yielding proceeds of approximately $228,000" the court papers said.

One day later, on October 5th, it was announced that Martha resigned from her post as a director of the New York Stock Exchange-a post she held only four months-and the price of MSO shares declined more than 7 percent to $6.32 in afternoon trading. From June 12th to October 12th, the share price of MSO had declined by approximately 61 percent.

Martha's future took a further interesting turn on October 15th, when Sam Waksal pleaded guilty to six counts of his indictment, including: bank fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and perjury. But he did not agree to cooperate with prosecutors, and did not incriminate Martha. Waksal's sentencing was postponed until 2003 so his lawyers could exchange information with U.S. District Judge William Pauley concerning Waksal's financial records.

After October 15th, the price of MSO shares rose, perhaps as the prospect of Martha's going to jail appeared to become more remote, and/or people began to consider MSO to be more than just Martha and her reputation. The gain from the low point of the MSO share price in October to December 9, 2002, was about 40 percent.

Martha still had a lot to think about, however. Apparently the SEC gave Martha notice in September of its intent to file civil securities fraud charges against her. Martha's lawyers responded and the SEC deliberated. Even if Martha were to get off with a fine, prosecutors could still bring a criminal case against her in the future. It is an interesting legal question, how, if Martha were to plead guilty to the civil charges, she could avoid criminal liability.

On June 4, 2003, Stewart was indicted on charges of obstructing justice and securities fraud. She then quit as Chairman and CEO of her company, but stayed on the Board and served as Chief Creative Officer. She appeared in court on January 20, 2004, and watched the proceedings throughout her trial. In addition to the testimony of Mr. Faneuil, Stewart's personal friend Mariana Pasternak testified that Stewart told her Waksal was trying to dump his shares shortly after selling her Imclone stock.24 Ultimately, the jury did not believe the counterclaim by Peter Bacanovic, Stewart's broker, that he and Martha had a prior agreement to sell Imclone if it went below $60. Although Judge Cedarbaum dismissed the charge of securities fraud for insider trading, on March 5, 2004, the jury found Stewart guilty on one charge of conspiracy, one of obstruction of justice, and two of making false statements to investigators. 25 The announcement caused the share price of her company to sink by $2.77 to $11.26 on the NYSE.

Martha immediately posted the following on her website:

I am obviously distressed by the jury's verdict, but I continue to take comfort in knowing that I have done nothing wrong and that I have the enduring support of my family and friends. I will appeal the verdict and continue to fight to clear my name. I believe in the fairness of the judicial system and remain confident that I will ultimately prevail.

Martha was subsequently sentenced to 5 months in prison and 5 months of home detention-a lower than maximum sentence under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines-and she did appeal. Although she could have remained free during the appeal, on September 15, 2004, she asked for her sentence to start so she could be at home in time for the spring planting season. Martha's appeal cited "prosecutorial misconduct, extraneous influences on the jury and erroneous evidentiary rulings and jury instructions" but on January 6, 2006, her conviction was upheld.

Impact on Reputation

Martha may still disagree with the verdict. But there is little doubt that the allegations and her convictions had a major impact on Martha personally, and on the fortunes of MSO and the other shareholders that had faith in her and her company. Assuming a value per share of $13.50 on June 12th, the decline to a low of $5.26 in early October 2003 represents a loss of market capitalization (i.e., reputation capital as defined by Charles Fombrun30) of approximately $250 million, or 61 percent. The value of MSO's shares did return to close at $35.51 on February 7, 2005,31 but fell off to under $20 in early 2006. According to a New York brand-rating company, Brand-Keys, the Martha Stewart brand reached a peak of 120 (the baseline is 100) in May 2002, and sank to a low of 63 in March 2004.

What will the future hold? Martha has returned to TV with a version of The Apprentice as well as her usual homemaking and design shows, and her products and magazines continue to be sold. Will Martha regain her earlier distinction? Would she do it again to avoid losing $45,673?

Questions

Martha's overall net worth was huge relative to her investment in ImClone. Assuming she did not have inside information, was there any way she could have avoided the appearance of having it?

On TV daily as the reigning guru of homemaking, Martha is the multimillionaire proprietor, president, and driving force of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. (MSO), of which, on March 18, 2002, she owned 30,713,475 (62.6 percent) of the class A, and 30,619,375 (100 percent) of the class B shares. On December 27, 2001, Martha's class A and class B shares were worth approximately $17 each, so on paper Martha's MSO class A shares alone were worth over $500 million. Class B shares are convertible into class A shares on a oneto- one basis.

Martha's personal life became public. The world did not know that Martha Stewart had sold 3,928 shares of ImClone for $58 each on December 27, 2001,until it surfaced in June 2002. The sale generated only $227,824 for Martha, and she avoided losing $45,673 when the stock price dropped the next day, but it has caused her endless personal grief and humiliation, and the loss of reputation, as well as a significant drop to $5.26 in the MSO share price.

What Happened?

Martha had made an investment in ImClone, a company that was trying to get the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to bring to market an anti-colon cancer drug called Erbitux. Samuel Waksal, then the CEO of ImClone and a personal friend of Martha's, was apparently warned on or close to December 25, 2001, that the FDA was going to refuse5 to review Erbitux. According to SEC allegations, Sam relayed the information to his family so they could dump their ImClone shares on an unsuspecting public before the official announcement. Martha claims that she didn't get any inside information early from Sam, but regulators believe that she may have or from her broker or her broker's aide. The activities of several of Sam's friends, including Martha, are under investigation by the SEC.

Sam was arrested on June 12, 2002, and charged with "nine criminal counts of conspiracy, securities fraud and perjury, and then freed on $10 million bail." In a related civil complaint, the SEC alleged that Sam "tried to sell ImClone stock and tipped family members before ImClone's official FDA announcement on Dec. 28."

According to the SEC, two unidentified members of Sam's family sold about $10 million worth of ImClone stock in a twoday interval just before the announcement. Moreover, Sam also tried for two days to sell nearly 80,000 ImClone shares for about $5 million, but two different brokers refused to process the trades.

Martha has denied any wrongdoing. She was quoted as saying: "In placing my trade I had no improper information…. My transaction was entirely lawful." She admitted calling Sam after selling her shares, but claimed: "I did not reach Mr. Waksal, and he did not return my call." She maintained that she had an agreement with her broker to sell her remaining ImClone shares "if the stock dropped below $60 per share."

Martha's public, however, was skeptical. She was asked embarrassing questions when she appeared on TV for a cooking segment, and she declined to answer saying: "I am here to make my salad." Martha's interactions with her broker, Peter Bacanovic, and his assistant, Douglas Faneuil, are also being scrutinized. Merrill Lynch Co. suspended Bacanovic (who was also Sam Waksal's broker) and Faneuil, with pay, in late June. Later, since all phone calls to brokerages are taped and emails kept, it appeared to be damning when Bacanovic initially refused to provide his cell phone records to the House Energy and Commerce Commission for their investigation. Moreover, on October 4, 2001, Faneuil "pleaded guilty to a charge that he accepted gifts from his superior in return for keeping quiet about circumstances surrounding Stewart's controversial stock sale." Faneuil admitted that he received extra vacation time, including a free airline ticket from a Merrill Lynch employee in exchange for withholding information from SEC and FBI investigators.

According to the Washington Post report of Faneuil's appearance in court:

On the morning of Dec. 27, Faneuil received a telephone call from a Waksal family member who asked to sell 39,472 shares for almost $2.5 million, according to court records. Waksal's accountant also called Faneuil in an unsuccessful attempt to sell a large bloc of shares, the records show. Prosecutors allege that those orders "constituted material non-public information." But they alleged that Faneuil violated his duty to Merrill Lynch by calling a "tippee" to relate that Waksal family members were attempting to liquidate their holdings in ImClone. That person then sold "all the Tippee's shares of ImClone stock, approximately 3,928 shares, yielding proceeds of approximately $228,000" the court papers said.

One day later, on October 5th, it was announced that Martha resigned from her post as a director of the New York Stock Exchange-a post she held only four months-and the price of MSO shares declined more than 7 percent to $6.32 in afternoon trading. From June 12th to October 12th, the share price of MSO had declined by approximately 61 percent.

Martha's future took a further interesting turn on October 15th, when Sam Waksal pleaded guilty to six counts of his indictment, including: bank fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and perjury. But he did not agree to cooperate with prosecutors, and did not incriminate Martha. Waksal's sentencing was postponed until 2003 so his lawyers could exchange information with U.S. District Judge William Pauley concerning Waksal's financial records.

After October 15th, the price of MSO shares rose, perhaps as the prospect of Martha's going to jail appeared to become more remote, and/or people began to consider MSO to be more than just Martha and her reputation. The gain from the low point of the MSO share price in October to December 9, 2002, was about 40 percent.

Martha still had a lot to think about, however. Apparently the SEC gave Martha notice in September of its intent to file civil securities fraud charges against her. Martha's lawyers responded and the SEC deliberated. Even if Martha were to get off with a fine, prosecutors could still bring a criminal case against her in the future. It is an interesting legal question, how, if Martha were to plead guilty to the civil charges, she could avoid criminal liability.

On June 4, 2003, Stewart was indicted on charges of obstructing justice and securities fraud. She then quit as Chairman and CEO of her company, but stayed on the Board and served as Chief Creative Officer. She appeared in court on January 20, 2004, and watched the proceedings throughout her trial. In addition to the testimony of Mr. Faneuil, Stewart's personal friend Mariana Pasternak testified that Stewart told her Waksal was trying to dump his shares shortly after selling her Imclone stock.24 Ultimately, the jury did not believe the counterclaim by Peter Bacanovic, Stewart's broker, that he and Martha had a prior agreement to sell Imclone if it went below $60. Although Judge Cedarbaum dismissed the charge of securities fraud for insider trading, on March 5, 2004, the jury found Stewart guilty on one charge of conspiracy, one of obstruction of justice, and two of making false statements to investigators. 25 The announcement caused the share price of her company to sink by $2.77 to $11.26 on the NYSE.

Martha immediately posted the following on her website:

I am obviously distressed by the jury's verdict, but I continue to take comfort in knowing that I have done nothing wrong and that I have the enduring support of my family and friends. I will appeal the verdict and continue to fight to clear my name. I believe in the fairness of the judicial system and remain confident that I will ultimately prevail.

Martha was subsequently sentenced to 5 months in prison and 5 months of home detention-a lower than maximum sentence under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines-and she did appeal. Although she could have remained free during the appeal, on September 15, 2004, she asked for her sentence to start so she could be at home in time for the spring planting season. Martha's appeal cited "prosecutorial misconduct, extraneous influences on the jury and erroneous evidentiary rulings and jury instructions" but on January 6, 2006, her conviction was upheld.

Impact on Reputation

Martha may still disagree with the verdict. But there is little doubt that the allegations and her convictions had a major impact on Martha personally, and on the fortunes of MSO and the other shareholders that had faith in her and her company. Assuming a value per share of $13.50 on June 12th, the decline to a low of $5.26 in early October 2003 represents a loss of market capitalization (i.e., reputation capital as defined by Charles Fombrun30) of approximately $250 million, or 61 percent. The value of MSO's shares did return to close at $35.51 on February 7, 2005,31 but fell off to under $20 in early 2006. According to a New York brand-rating company, Brand-Keys, the Martha Stewart brand reached a peak of 120 (the baseline is 100) in May 2002, and sank to a low of 63 in March 2004.

What will the future hold? Martha has returned to TV with a version of The Apprentice as well as her usual homemaking and design shows, and her products and magazines continue to be sold. Will Martha regain her earlier distinction? Would she do it again to avoid losing $45,673?

Questions

Martha's overall net worth was huge relative to her investment in ImClone. Assuming she did not have inside information, was there any way she could have avoided the appearance of having it?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

What are the common elements of the three practical approaches to ethical decision making that are briefly outlined in this chapter?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

In July of 2008, Virgin Mobile USA began a 'Strip2Clothe' advertising campaign. There are millions of homeless teenagers in the United States, and Virgin Mobile's website said "someone out there needs clothes more than you." Virgin Mobile invited teenagers to upload videos of themselves disrobing. For every uploaded striptease video, Virgin Mobile would donate a new piece of clothing. For every five times the video was viewed, an additional piece of clothing would be donated. Virgin Mobile said that they would screen all the videos. The strippers had to be 18 or older, and there was to be no full nudity. By July 12, there were 20 videos on the site that had generated 51,291 pieces of donated clothing.

The campaign sparked immediate criticism. Rebecca Lentz of The Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis called the advertising campaign "distasteful and inappropriate and exploitative." Parents were concerned that their under 18 year-old children would strip, zip the video, and not reveal their real age. On Tuesday July 15, The National Network for Youth (NN4Y) said that it would decline to partner with Virgin Mobile. Some of the 150 charities represented by NN4Y objected to the campaign saying that it was inappropriate given that many homeless teenagers are sexually exploited. NN4Y said that any member organizations that wished to receive clothing donations through the Strip2Clothe campaign would have to contact Virgin Mobile directly.

In response to the public outcry, Virgin Mobile altered its campaign. On July 21, it launched 'Blank2Clothe' in which the company would accept any kind of talent video such as walking, juggling, singing, riding, and so on. All of the striptease videos were removed and the strippers were asked to send in new, fully clothed videos.

The arguments against the campaign were that: it targeted youth; many homeless teenagers are sexually exploited; the homeless normally need shelter and safety rather than clothes; and the campaign was in poor taste. But there were some supporters. Rick Koca, founder of StandUp For Kids in San Diego, said that the campaign wasn't hurting anyone and was raising public awareness. In the one week ending July 19, the controversy and the campaign had resulted in a further 15,000 clothing donations.

The Strip2Clothe campaign may have been in questionable taste, but it did raise tens of thousands of pieces of clothing for the homeless. Does the end justify the means?

The campaign sparked immediate criticism. Rebecca Lentz of The Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis called the advertising campaign "distasteful and inappropriate and exploitative." Parents were concerned that their under 18 year-old children would strip, zip the video, and not reveal their real age. On Tuesday July 15, The National Network for Youth (NN4Y) said that it would decline to partner with Virgin Mobile. Some of the 150 charities represented by NN4Y objected to the campaign saying that it was inappropriate given that many homeless teenagers are sexually exploited. NN4Y said that any member organizations that wished to receive clothing donations through the Strip2Clothe campaign would have to contact Virgin Mobile directly.

In response to the public outcry, Virgin Mobile altered its campaign. On July 21, it launched 'Blank2Clothe' in which the company would accept any kind of talent video such as walking, juggling, singing, riding, and so on. All of the striptease videos were removed and the strippers were asked to send in new, fully clothed videos.

The arguments against the campaign were that: it targeted youth; many homeless teenagers are sexually exploited; the homeless normally need shelter and safety rather than clothes; and the campaign was in poor taste. But there were some supporters. Rick Koca, founder of StandUp For Kids in San Diego, said that the campaign wasn't hurting anyone and was raising public awareness. In the one week ending July 19, the controversy and the campaign had resulted in a further 15,000 clothing donations.

The Strip2Clothe campaign may have been in questionable taste, but it did raise tens of thousands of pieces of clothing for the homeless. Does the end justify the means?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

On February 11, 2010, the leaders of the European Union (EU) agreed on a plan to bail out Greece, a country that had joined the EU in 1981 and was admitted to the European Monetary Union (EMU) allowing Greece to adopt the Euro as its currency in 2001. Greece had been unable to pay its bills, or to borrow more money to do so because it had overspent its income on its social programs and other projects. In the aftermath of providing Greece with bailout credit ultimately totaling €100 billion ($147 billion), questions were asked about how this could have happened. A spotlight was brought to bear on how Goldman Sachs (GS) had enabled Greece to qualify for adopting the Euro in the first place, and for providing the means to hide some transactions in which Greece pledged its future revenues in return for instant cash to spend. In a sense, GS helped Greece draw a veil over its finances with arrangements that were not transparent.

In 2001, Greece wanted to join the EMU but faced a requirement that its debt-to-GDP ratio be less than 60%.3 Unfortunately, Greece had some debt that was payable in U.S. dollars (USD) and other debt in Japanese Yen. Both currencies had grown in value relative to the Euro in 1999 and 2000. Under EU rules, such unhedged debt had to be valued and reported at the year-end exchange rates, so Greece faced the prospect reporting increased debt liabilities.

In late 2000 and 2001, GS proposed and arranged two types of hedges that reduced reported Greek debt by €2.367 billion, and allowed Greece to access unreported, off-balance sheet financing:

• Currency hedges that turned the USD and Yen debt payments into Euro payments, and subsequently the Greek swap portfolio into new cross currency swaps valued using a historical implied foreign exchange rate rather than market value exchange rate. Since the historical exchange rate was lower than the market rate at the time, the resulting valuation of the debt was reduced by almost €2.4 billion ($3.2 billion).

• Interest rate swaps that, when coupled with a bond, provided Greece with instant cash in 2001 in return for pledging future landing fees at its airports. GS was reportedly paid $300 million for this transaction. A similar deal in 2000 saw Greece pledge the future revenue from its national lottery in return for cash. Greece was obligated to pay GS substantial amounts until 2019 under these agreements, but chose to sell these interest rate swaps to the National Bank of Greece in 2005 after criticism in the Greek Parliament.

In essence, through these so-called interest rate swaps, Greece was converting a stream of variable future cash flows into instant cash. But, although there was a fierce debate among EU finance ministers, these obligations to pay out future cash flows were not required to be disclosed in 2001 and were therefore a type of "offbalance sheet financing." In 2002, the requirements changed and these obligations did require disclosure. Humorously, the 2000 deal related to a legal entity called Aeolos that was created for the purpose- Aeolos is the Greek goddess of wind.

In response to public criticism, GS argues on its website that "these transactions [both currency and interest rate hedges] were consistent with the Eurostat principles governing their use and disclosure at the time." In addition, GS argues that the reduction of €2.367 billion had "minimal effect on the country's overall fiscal situation in 2001" since its GDP was approximately $131 billion and its debt was 103.7% of GDP. However, it is not clear how much cash was provided by the so-called interest rate swaps that allowed Greece to report lower debt obligations in total.

What subsequent impacts could the transactions described above have on Goldman Sachs?

In 2001, Greece wanted to join the EMU but faced a requirement that its debt-to-GDP ratio be less than 60%.3 Unfortunately, Greece had some debt that was payable in U.S. dollars (USD) and other debt in Japanese Yen. Both currencies had grown in value relative to the Euro in 1999 and 2000. Under EU rules, such unhedged debt had to be valued and reported at the year-end exchange rates, so Greece faced the prospect reporting increased debt liabilities.

In late 2000 and 2001, GS proposed and arranged two types of hedges that reduced reported Greek debt by €2.367 billion, and allowed Greece to access unreported, off-balance sheet financing:

• Currency hedges that turned the USD and Yen debt payments into Euro payments, and subsequently the Greek swap portfolio into new cross currency swaps valued using a historical implied foreign exchange rate rather than market value exchange rate. Since the historical exchange rate was lower than the market rate at the time, the resulting valuation of the debt was reduced by almost €2.4 billion ($3.2 billion).

• Interest rate swaps that, when coupled with a bond, provided Greece with instant cash in 2001 in return for pledging future landing fees at its airports. GS was reportedly paid $300 million for this transaction. A similar deal in 2000 saw Greece pledge the future revenue from its national lottery in return for cash. Greece was obligated to pay GS substantial amounts until 2019 under these agreements, but chose to sell these interest rate swaps to the National Bank of Greece in 2005 after criticism in the Greek Parliament.

In essence, through these so-called interest rate swaps, Greece was converting a stream of variable future cash flows into instant cash. But, although there was a fierce debate among EU finance ministers, these obligations to pay out future cash flows were not required to be disclosed in 2001 and were therefore a type of "offbalance sheet financing." In 2002, the requirements changed and these obligations did require disclosure. Humorously, the 2000 deal related to a legal entity called Aeolos that was created for the purpose- Aeolos is the Greek goddess of wind.

In response to public criticism, GS argues on its website that "these transactions [both currency and interest rate hedges] were consistent with the Eurostat principles governing their use and disclosure at the time." In addition, GS argues that the reduction of €2.367 billion had "minimal effect on the country's overall fiscal situation in 2001" since its GDP was approximately $131 billion and its debt was 103.7% of GDP. However, it is not clear how much cash was provided by the so-called interest rate swaps that allowed Greece to report lower debt obligations in total.

What subsequent impacts could the transactions described above have on Goldman Sachs?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

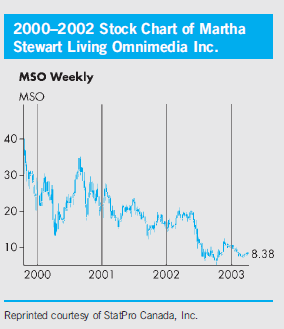

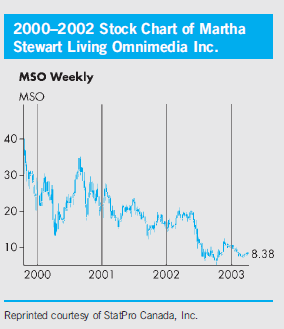

In June 2002, Martha Stewart began to wrestle with allegations that she had improperly used inside information to sell a stock investment to an unsuspecting investing public. That was when her personal friend Sam Waksal was defending himself against Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) allegations that he had tipped off his family members so they could sell their shares of ImClone Systems Inc. (ImClone) just before other investors learned that ImClone's fortunes were about to take a dive. Observers presumed that Martha was also tipped off and, even though she proclaimed her innocence, the rumors would not go away.

On TV daily as the reigning guru of homemaking, Martha is the multimillionaire proprietor, president, and driving force of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. (MSO), of which, on March 18, 2002, she owned 30,713,475 (62.6 percent) of the class A, and 30,619,375 (100 percent) of the class B shares. On December 27, 2001, Martha's class A and class B shares were worth approximately $17 each, so on paper Martha's MSO class A shares alone were worth over $500 million. Class B shares are convertible into class A shares on a oneto- one basis.

Martha's personal life became public. The world did not know that Martha Stewart had sold 3,928 shares of ImClone for $58 each on December 27, 2001,until it surfaced in June 2002. The sale generated only $227,824 for Martha, and she avoided losing $45,673 when the stock price dropped the next day, but it has caused her endless personal grief and humiliation, and the loss of reputation, as well as a significant drop to $5.26 in the MSO share price.

What Happened?

Martha had made an investment in ImClone, a company that was trying to get the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to bring to market an anti-colon cancer drug called Erbitux. Samuel Waksal, then the CEO of ImClone and a personal friend of Martha's, was apparently warned on or close to December 25, 2001, that the FDA was going to refuse5 to review Erbitux. According to SEC allegations, Sam relayed the information to his family so they could dump their ImClone shares on an unsuspecting public before the official announcement. Martha claims that she didn't get any inside information early from Sam, but regulators believe that she may have or from her broker or her broker's aide. The activities of several of Sam's friends, including Martha, are under investigation by the SEC.

Sam was arrested on June 12, 2002, and charged with "nine criminal counts of conspiracy, securities fraud and perjury, and then freed on $10 million bail." In a related civil complaint, the SEC alleged that Sam "tried to sell ImClone stock and tipped family members before ImClone's official FDA announcement on Dec. 28."

According to the SEC, two unidentified members of Sam's family sold about $10 million worth of ImClone stock in a twoday interval just before the announcement. Moreover, Sam also tried for two days to sell nearly 80,000 ImClone shares for about $5 million, but two different brokers refused to process the trades.

Martha has denied any wrongdoing. She was quoted as saying: "In placing my trade I had no improper information…. My transaction was entirely lawful." She admitted calling Sam after selling her shares, but claimed: "I did not reach Mr. Waksal, and he did not return my call." She maintained that she had an agreement with her broker to sell her remaining ImClone shares "if the stock dropped below $60 per share."

Martha's public, however, was skeptical. She was asked embarrassing questions when she appeared on TV for a cooking segment, and she declined to answer saying: "I am here to make my salad." Martha's interactions with her broker, Peter Bacanovic, and his assistant, Douglas Faneuil, are also being scrutinized. Merrill Lynch Co. suspended Bacanovic (who was also Sam Waksal's broker) and Faneuil, with pay, in late June. Later, since all phone calls to brokerages are taped and emails kept, it appeared to be damning when Bacanovic initially refused to provide his cell phone records to the House Energy and Commerce Commission for their investigation. Moreover, on October 4, 2001, Faneuil "pleaded guilty to a charge that he accepted gifts from his superior in return for keeping quiet about circumstances surrounding Stewart's controversial stock sale." Faneuil admitted that he received extra vacation time, including a free airline ticket from a Merrill Lynch employee in exchange for withholding information from SEC and FBI investigators.

According to the Washington Post report of Faneuil's appearance in court:

On the morning of Dec. 27, Faneuil received a telephone call from a Waksal family member who asked to sell 39,472 shares for almost $2.5 million, according to court records. Waksal's accountant also called Faneuil in an unsuccessful attempt to sell a large bloc of shares, the records show. Prosecutors allege that those orders "constituted material non-public information." But they alleged that Faneuil violated his duty to Merrill Lynch by calling a "tippee" to relate that Waksal family members were attempting to liquidate their holdings in ImClone. That person then sold "all the Tippee's shares of ImClone stock, approximately 3,928 shares, yielding proceeds of approximately $228,000" the court papers said.

One day later, on October 5th, it was announced that Martha resigned from her post as a director of the New York Stock Exchange-a post she held only four months-and the price of MSO shares declined more than 7 percent to $6.32 in afternoon trading. From June 12th to October 12th, the share price of MSO had declined by approximately 61 percent.

Martha's future took a further interesting turn on October 15th, when Sam Waksal pleaded guilty to six counts of his indictment, including: bank fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and perjury. But he did not agree to cooperate with prosecutors, and did not incriminate Martha. Waksal's sentencing was postponed until 2003 so his lawyers could exchange information with U.S. District Judge William Pauley concerning Waksal's financial records.

After October 15th, the price of MSO shares rose, perhaps as the prospect of Martha's going to jail appeared to become more remote, and/or people began to consider MSO to be more than just Martha and her reputation. The gain from the low point of the MSO share price in October to December 9, 2002, was about 40 percent.

Martha still had a lot to think about, however. Apparently the SEC gave Martha notice in September of its intent to file civil securities fraud charges against her. Martha's lawyers responded and the SEC deliberated. Even if Martha were to get off with a fine, prosecutors could still bring a criminal case against her in the future. It is an interesting legal question, how, if Martha were to plead guilty to the civil charges, she could avoid criminal liability.

On June 4, 2003, Stewart was indicted on charges of obstructing justice and securities fraud. She then quit as Chairman and CEO of her company, but stayed on the Board and served as Chief Creative Officer. She appeared in court on January 20, 2004, and watched the proceedings throughout her trial. In addition to the testimony of Mr. Faneuil, Stewart's personal friend Mariana Pasternak testified that Stewart told her Waksal was trying to dump his shares shortly after selling her Imclone stock.24 Ultimately, the jury did not believe the counterclaim by Peter Bacanovic, Stewart's broker, that he and Martha had a prior agreement to sell Imclone if it went below $60. Although Judge Cedarbaum dismissed the charge of securities fraud for insider trading, on March 5, 2004, the jury found Stewart guilty on one charge of conspiracy, one of obstruction of justice, and two of making false statements to investigators. 25 The announcement caused the share price of her company to sink by $2.77 to $11.26 on the NYSE.

Martha immediately posted the following on her website:

I am obviously distressed by the jury's verdict, but I continue to take comfort in knowing that I have done nothing wrong and that I have the enduring support of my family and friends. I will appeal the verdict and continue to fight to clear my name. I believe in the fairness of the judicial system and remain confident that I will ultimately prevail.

Martha was subsequently sentenced to 5 months in prison and 5 months of home detention-a lower than maximum sentence under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines-and she did appeal. Although she could have remained free during the appeal, on September 15, 2004, she asked for her sentence to start so she could be at home in time for the spring planting season. Martha's appeal cited "prosecutorial misconduct, extraneous influences on the jury and erroneous evidentiary rulings and jury instructions" but on January 6, 2006, her conviction was upheld.

Impact on Reputation

Martha may still disagree with the verdict. But there is little doubt that the allegations and her convictions had a major impact on Martha personally, and on the fortunes of MSO and the other shareholders that had faith in her and her company. Assuming a value per share of $13.50 on June 12th, the decline to a low of $5.26 in early October 2003 represents a loss of market capitalization (i.e., reputation capital as defined by Charles Fombrun30) of approximately $250 million, or 61 percent. The value of MSO's shares did return to close at $35.51 on February 7, 2005,31 but fell off to under $20 in early 2006. According to a New York brand-rating company, Brand-Keys, the Martha Stewart brand reached a peak of 120 (the baseline is 100) in May 2002, and sank to a low of 63 in March 2004.

What will the future hold? Martha has returned to TV with a version of The Apprentice as well as her usual homemaking and design shows, and her products and magazines continue to be sold. Will Martha regain her earlier distinction? Would she do it again to avoid losing $45,673?

Questions

How could Martha have handled this crisis better?

On TV daily as the reigning guru of homemaking, Martha is the multimillionaire proprietor, president, and driving force of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. (MSO), of which, on March 18, 2002, she owned 30,713,475 (62.6 percent) of the class A, and 30,619,375 (100 percent) of the class B shares. On December 27, 2001, Martha's class A and class B shares were worth approximately $17 each, so on paper Martha's MSO class A shares alone were worth over $500 million. Class B shares are convertible into class A shares on a oneto- one basis.

Martha's personal life became public. The world did not know that Martha Stewart had sold 3,928 shares of ImClone for $58 each on December 27, 2001,until it surfaced in June 2002. The sale generated only $227,824 for Martha, and she avoided losing $45,673 when the stock price dropped the next day, but it has caused her endless personal grief and humiliation, and the loss of reputation, as well as a significant drop to $5.26 in the MSO share price.

What Happened?

Martha had made an investment in ImClone, a company that was trying to get the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to bring to market an anti-colon cancer drug called Erbitux. Samuel Waksal, then the CEO of ImClone and a personal friend of Martha's, was apparently warned on or close to December 25, 2001, that the FDA was going to refuse5 to review Erbitux. According to SEC allegations, Sam relayed the information to his family so they could dump their ImClone shares on an unsuspecting public before the official announcement. Martha claims that she didn't get any inside information early from Sam, but regulators believe that she may have or from her broker or her broker's aide. The activities of several of Sam's friends, including Martha, are under investigation by the SEC.

Sam was arrested on June 12, 2002, and charged with "nine criminal counts of conspiracy, securities fraud and perjury, and then freed on $10 million bail." In a related civil complaint, the SEC alleged that Sam "tried to sell ImClone stock and tipped family members before ImClone's official FDA announcement on Dec. 28."

According to the SEC, two unidentified members of Sam's family sold about $10 million worth of ImClone stock in a twoday interval just before the announcement. Moreover, Sam also tried for two days to sell nearly 80,000 ImClone shares for about $5 million, but two different brokers refused to process the trades.

Martha has denied any wrongdoing. She was quoted as saying: "In placing my trade I had no improper information…. My transaction was entirely lawful." She admitted calling Sam after selling her shares, but claimed: "I did not reach Mr. Waksal, and he did not return my call." She maintained that she had an agreement with her broker to sell her remaining ImClone shares "if the stock dropped below $60 per share."

Martha's public, however, was skeptical. She was asked embarrassing questions when she appeared on TV for a cooking segment, and she declined to answer saying: "I am here to make my salad." Martha's interactions with her broker, Peter Bacanovic, and his assistant, Douglas Faneuil, are also being scrutinized. Merrill Lynch Co. suspended Bacanovic (who was also Sam Waksal's broker) and Faneuil, with pay, in late June. Later, since all phone calls to brokerages are taped and emails kept, it appeared to be damning when Bacanovic initially refused to provide his cell phone records to the House Energy and Commerce Commission for their investigation. Moreover, on October 4, 2001, Faneuil "pleaded guilty to a charge that he accepted gifts from his superior in return for keeping quiet about circumstances surrounding Stewart's controversial stock sale." Faneuil admitted that he received extra vacation time, including a free airline ticket from a Merrill Lynch employee in exchange for withholding information from SEC and FBI investigators.

According to the Washington Post report of Faneuil's appearance in court:

On the morning of Dec. 27, Faneuil received a telephone call from a Waksal family member who asked to sell 39,472 shares for almost $2.5 million, according to court records. Waksal's accountant also called Faneuil in an unsuccessful attempt to sell a large bloc of shares, the records show. Prosecutors allege that those orders "constituted material non-public information." But they alleged that Faneuil violated his duty to Merrill Lynch by calling a "tippee" to relate that Waksal family members were attempting to liquidate their holdings in ImClone. That person then sold "all the Tippee's shares of ImClone stock, approximately 3,928 shares, yielding proceeds of approximately $228,000" the court papers said.

One day later, on October 5th, it was announced that Martha resigned from her post as a director of the New York Stock Exchange-a post she held only four months-and the price of MSO shares declined more than 7 percent to $6.32 in afternoon trading. From June 12th to October 12th, the share price of MSO had declined by approximately 61 percent.

Martha's future took a further interesting turn on October 15th, when Sam Waksal pleaded guilty to six counts of his indictment, including: bank fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and perjury. But he did not agree to cooperate with prosecutors, and did not incriminate Martha. Waksal's sentencing was postponed until 2003 so his lawyers could exchange information with U.S. District Judge William Pauley concerning Waksal's financial records.

After October 15th, the price of MSO shares rose, perhaps as the prospect of Martha's going to jail appeared to become more remote, and/or people began to consider MSO to be more than just Martha and her reputation. The gain from the low point of the MSO share price in October to December 9, 2002, was about 40 percent.

Martha still had a lot to think about, however. Apparently the SEC gave Martha notice in September of its intent to file civil securities fraud charges against her. Martha's lawyers responded and the SEC deliberated. Even if Martha were to get off with a fine, prosecutors could still bring a criminal case against her in the future. It is an interesting legal question, how, if Martha were to plead guilty to the civil charges, she could avoid criminal liability.

On June 4, 2003, Stewart was indicted on charges of obstructing justice and securities fraud. She then quit as Chairman and CEO of her company, but stayed on the Board and served as Chief Creative Officer. She appeared in court on January 20, 2004, and watched the proceedings throughout her trial. In addition to the testimony of Mr. Faneuil, Stewart's personal friend Mariana Pasternak testified that Stewart told her Waksal was trying to dump his shares shortly after selling her Imclone stock.24 Ultimately, the jury did not believe the counterclaim by Peter Bacanovic, Stewart's broker, that he and Martha had a prior agreement to sell Imclone if it went below $60. Although Judge Cedarbaum dismissed the charge of securities fraud for insider trading, on March 5, 2004, the jury found Stewart guilty on one charge of conspiracy, one of obstruction of justice, and two of making false statements to investigators. 25 The announcement caused the share price of her company to sink by $2.77 to $11.26 on the NYSE.

Martha immediately posted the following on her website:

I am obviously distressed by the jury's verdict, but I continue to take comfort in knowing that I have done nothing wrong and that I have the enduring support of my family and friends. I will appeal the verdict and continue to fight to clear my name. I believe in the fairness of the judicial system and remain confident that I will ultimately prevail.

Martha was subsequently sentenced to 5 months in prison and 5 months of home detention-a lower than maximum sentence under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines-and she did appeal. Although she could have remained free during the appeal, on September 15, 2004, she asked for her sentence to start so she could be at home in time for the spring planting season. Martha's appeal cited "prosecutorial misconduct, extraneous influences on the jury and erroneous evidentiary rulings and jury instructions" but on January 6, 2006, her conviction was upheld.

Impact on Reputation

Martha may still disagree with the verdict. But there is little doubt that the allegations and her convictions had a major impact on Martha personally, and on the fortunes of MSO and the other shareholders that had faith in her and her company. Assuming a value per share of $13.50 on June 12th, the decline to a low of $5.26 in early October 2003 represents a loss of market capitalization (i.e., reputation capital as defined by Charles Fombrun30) of approximately $250 million, or 61 percent. The value of MSO's shares did return to close at $35.51 on February 7, 2005,31 but fell off to under $20 in early 2006. According to a New York brand-rating company, Brand-Keys, the Martha Stewart brand reached a peak of 120 (the baseline is 100) in May 2002, and sank to a low of 63 in March 2004.

What will the future hold? Martha has returned to TV with a version of The Apprentice as well as her usual homemaking and design shows, and her products and magazines continue to be sold. Will Martha regain her earlier distinction? Would she do it again to avoid losing $45,673?

Questions

How could Martha have handled this crisis better?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Is a professional accountant a businessperson pursuing profit or a fiduciary that is to act in the public interest?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 62 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

"Sam, I'm really in trouble. I've always wanted to be an accountant. But here I am just about to apply to the accounting firms for a job after graduation from the university, and I'm not sure I want to be an accountant after all."

"Why, Norm? In all those accounting courses we took together, you worked super hard because you were really interested. What's your problem now?"