Deck 6: Consumers, Producers and the Efficiency of Markets

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/19

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 6: Consumers, Producers and the Efficiency of Markets

1

LAW OF DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY Some restaurants offer "all you can eat" meals. How is this practice related to diminishing marginal utility? What restrictions must the restaurant impose on the customer to make a profit?

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

Some restaurants offer "all you can eat" meals. The marginal utility derived from each additional plate of food will start diminishing once the consumer becomes full.

The marginal utility will continue to decrease until it reaches zero; and once the consumer becomes full, his/her marginal utility becomes negative.In order to make profit, restaurants should not allow consumers to share food with other consumers and also should not allow consumers to tak e away food to their home.

Some restaurants offer "all you can eat" meals. The marginal utility derived from each additional plate of food will start diminishing once the consumer becomes full.

The marginal utility will continue to decrease until it reaches zero; and once the consumer becomes full, his/her marginal utility becomes negative.In order to make profit, restaurants should not allow consumers to share food with other consumers and also should not allow consumers to tak e away food to their home.

2

LAW OF DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY Complete each of the following sentences:

a. Your tastes determine the _______ you derive from consuming a particular good.

b. _______ utility is the change in _______ utility resulting from a _______ change in the consumption of a good.

c. As long as marginal utility is positive, total utility is _______.

d. The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as an individual consumes more of a good during a given time period, other things constant, total utility _____.

a. Your tastes determine the _______ you derive from consuming a particular good.

b. _______ utility is the change in _______ utility resulting from a _______ change in the consumption of a good.

c. As long as marginal utility is positive, total utility is _______.

d. The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as an individual consumes more of a good during a given time period, other things constant, total utility _____.

Law of diminishing marginal utility

a.Your tastes determine the utility you derive from consuming a particular good.

b.Marginal utility is the change in total utility resulting from a one-unit change in the consumption of a good.

c.As long as marginal utility is positive, total utility is increasing.

d.The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as an individual consumes more of a good during a given time period, other things constant, total utility increases but at decreasing rate.

a.Your tastes determine the utility you derive from consuming a particular good.

b.Marginal utility is the change in total utility resulting from a one-unit change in the consumption of a good.

c.As long as marginal utility is positive, total utility is increasing.

d.The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as an individual consumes more of a good during a given time period, other things constant, total utility increases but at decreasing rate.

3

MARGINAL UTILITY Is it possible for marginal utility to be negative while total utility is positive? If yes, under what circumstances is it possible?

Marginal Utility

Marginal utility is a change in total utility from an additional unit of consumption made by a consumer.

Initially, when marginal utility increases, total utility increases at an increasing rate and after a certain point, it will start to decline; and then, total utility will increase at a decreasing rate.Once marginal utility becomes zero, the total utility would be at a maximum. After this level, marginal utility will become negative and total utility will start to decline.Total utility can be positive as long as the negative marginal utility is not large enough to completely offset the positive total utility.

Marginal utility is a change in total utility from an additional unit of consumption made by a consumer.

Initially, when marginal utility increases, total utility increases at an increasing rate and after a certain point, it will start to decline; and then, total utility will increase at a decreasing rate.Once marginal utility becomes zero, the total utility would be at a maximum. After this level, marginal utility will become negative and total utility will start to decline.Total utility can be positive as long as the negative marginal utility is not large enough to completely offset the positive total utility.

4

UTILITY-MAXIMIZING CONDITIONS For a particular consumer, the marginal utility of cookies equals the marginal utility of candy. If the price of a cookie is less than the price of candy, is the consumer in equilibrium? Why or why not? If not, what should the consumer do to attain equilibrium?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

UTILITY-MAXIMIZING CONDITIONS Suppose that marginal utility of Good X = 100, the price of X is $10 per unit, and the price of Y is $5 per unit. Assuming that the consumer is in equilibrium and is consuming both X and Y , what must the marginal utility of Y be?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

UTILITY-MAXIMIZING CONDITIONS Suppose that the price of X is twice the price of Y. You are a utility maximizer who allocates your budget between the two goods. What must be true about the equilibrium relationship between the marginal utility levels of the last unit consumed of each good? What must be true about the equilibrium relationship between the marginal utility levels of the last dollar spent on each good?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Case Study: Water, Water Everywhere What is the diamonds water paradox, and how is it explained? Use the same reasoning to explain why bottled water costs so much more than tap water.

Reference Case Study:

Bringing Theory to Life

Water, Water, Everywhere Centuries ago, economists puzzled over the price of diamonds relative to the price of water. Diamonds are mere bling--certainly not a necessity of life in any sense. Water is essential to life and has hundreds of valuable uses. Yet diamonds are expensive, while water is cheap. For example, the $10,000 spent on a high-quality one-carat diamond could buy about 10,000 bottles of water or about 2.8 million gallons of municipally supplied water (which sells for about 35 cents per 100 gallons in New York City). However measured, diamonds are extremely expensive relative to water. For the price of a one-carat diamond, you could buy enough water to last two lifetimes.

How can something as useful as water cost so much less than something of such limited use as diamonds? In 1776, Adam Smith discussed what has come to be called the diamonds-water paradox. Because water is essential to life, the total utility derived from water greatly exceeds the total utility derived from diamonds. Yet the market value of a good is based not on its total utility but on what consumers are willing and able to pay for an additional unit-that is, on its marginal utility. Because water is so abundant in nature, we consume it to the point where the marginal utility of the last gallon purchased is relatively low. Because diamonds are relatively scarce compared to water, the marginal utility of the last diamond purchased is relatively high. Thus, water is cheap and diamonds expensive. As Ben Franklin said "We will only know the worth of water when the well is dry."

Speaking of water, sales of bottled water are growing faster than any other beverage category-creating a $15 billion U.S. industry, an average of 25 gallons per person in 2010. Bottled water ranks behind only soft drinks in sales, outselling coffee, milk, and beer. The United States offers the world's largest market for bottled water-importing water from places such as Italy, France, Sweden, Wales, even Fiji. "Water bars" in cities such as Newport, Rhode Island, and San Francisco feature bottled water as the main attraction. A 9-ounce bottle of Evian water costs $1.49. That amounts to $21.19 per gallon, or nearly 10 times more than gasoline. You think that's pricey? Bling

is available in bottles decorated with Swarovski crystals and sells for more than $50 a bottle-that's about 100 times more than gasoline.

is available in bottles decorated with Swarovski crystals and sells for more than $50 a bottle-that's about 100 times more than gasoline.

Why would consumers pay a premium for bottled water when water from the tap costs virtually nothing? After all, some bottled water comes from municipal taps (for example, New York City water is also bottled and sold under the brand name Tap'dNY). First, many people do not view the two as good substitutes. Some people have concerns about the safety of tap water, and they consider bottled water a healthy alternative (about half those surveyed in a Gallup Poll said they won't drink water straight from the tap). Second, even those who drink tap water find bottled water a convenient option away from home. And third, some bottled water is now lightly flavored or fortified with vitamins. People who buy bottled water apparently feel the additional benefit offsets the additional cost.

Fast-food restaurants now offer bottled water as a healthy alternative to soft drinks. Soft-drink sales have been declining for more than a decade as bottled water sales have climbed. But if you can't fight 'em, join 'em: Pepsi's Aquafina is the top-selling bottled water in America, and Coke's Dasani ranks second.

Reference Case Study:

Bringing Theory to Life

Water, Water, Everywhere Centuries ago, economists puzzled over the price of diamonds relative to the price of water. Diamonds are mere bling--certainly not a necessity of life in any sense. Water is essential to life and has hundreds of valuable uses. Yet diamonds are expensive, while water is cheap. For example, the $10,000 spent on a high-quality one-carat diamond could buy about 10,000 bottles of water or about 2.8 million gallons of municipally supplied water (which sells for about 35 cents per 100 gallons in New York City). However measured, diamonds are extremely expensive relative to water. For the price of a one-carat diamond, you could buy enough water to last two lifetimes.

How can something as useful as water cost so much less than something of such limited use as diamonds? In 1776, Adam Smith discussed what has come to be called the diamonds-water paradox. Because water is essential to life, the total utility derived from water greatly exceeds the total utility derived from diamonds. Yet the market value of a good is based not on its total utility but on what consumers are willing and able to pay for an additional unit-that is, on its marginal utility. Because water is so abundant in nature, we consume it to the point where the marginal utility of the last gallon purchased is relatively low. Because diamonds are relatively scarce compared to water, the marginal utility of the last diamond purchased is relatively high. Thus, water is cheap and diamonds expensive. As Ben Franklin said "We will only know the worth of water when the well is dry."

Speaking of water, sales of bottled water are growing faster than any other beverage category-creating a $15 billion U.S. industry, an average of 25 gallons per person in 2010. Bottled water ranks behind only soft drinks in sales, outselling coffee, milk, and beer. The United States offers the world's largest market for bottled water-importing water from places such as Italy, France, Sweden, Wales, even Fiji. "Water bars" in cities such as Newport, Rhode Island, and San Francisco feature bottled water as the main attraction. A 9-ounce bottle of Evian water costs $1.49. That amounts to $21.19 per gallon, or nearly 10 times more than gasoline. You think that's pricey? Bling

is available in bottles decorated with Swarovski crystals and sells for more than $50 a bottle-that's about 100 times more than gasoline.

is available in bottles decorated with Swarovski crystals and sells for more than $50 a bottle-that's about 100 times more than gasoline.Why would consumers pay a premium for bottled water when water from the tap costs virtually nothing? After all, some bottled water comes from municipal taps (for example, New York City water is also bottled and sold under the brand name Tap'dNY). First, many people do not view the two as good substitutes. Some people have concerns about the safety of tap water, and they consider bottled water a healthy alternative (about half those surveyed in a Gallup Poll said they won't drink water straight from the tap). Second, even those who drink tap water find bottled water a convenient option away from home. And third, some bottled water is now lightly flavored or fortified with vitamins. People who buy bottled water apparently feel the additional benefit offsets the additional cost.

Fast-food restaurants now offer bottled water as a healthy alternative to soft drinks. Soft-drink sales have been declining for more than a decade as bottled water sales have climbed. But if you can't fight 'em, join 'em: Pepsi's Aquafina is the top-selling bottled water in America, and Coke's Dasani ranks second.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

CONSUMER SURPLUS The height of the demand curve at a given quantity reflects the marginal valuation of the last unit of that good consumed. For a normal good, an increase in income shifts the demand curve to the right and therefore increases its height at any quantity. Does this mean that consumers get greater marginal utility from each unit of this good than they did before? Explain.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Consumer Surplus Suppose the supply of a good is perfectly elastic at a price of $5. The market demand curve for this good is linear, with zero quantity demanded at a price of $25. Given that the slope of this linear demand curve is -0.25, draw a supply and demand graph to illustrate the consumer surplus that occurs when the market is in equilibrium.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Case Study: The Marginal Value of Free Medical Care

Medicare recipients pay a monthly premium for coverage, must meet an annual deductible, and have a co-payment for doctors' office visits. What impact would an increase in the monthly premium have on their consumer surplus? What would be the impact of a reduction in co-payments? President George W. Bush introduced some coverage of prescription medications. What is the impact on consumer surplus of offering some coverage for prescription medication?

Medicare recipients pay a monthly premium for coverage, must meet an annual deductible, and have a co-payment for doctors' office visits. What impact would an increase in the monthly premium have on their consumer surplus? What would be the impact of a reduction in co-payments? President George W. Bush introduced some coverage of prescription medications. What is the impact on consumer surplus of offering some coverage for prescription medication?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

ROLE OF TIME IN DEMAND In many amusement parks, you pay an admission fee to the park but you do not need to pay for individual rides. How do people choose which rides to go on?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

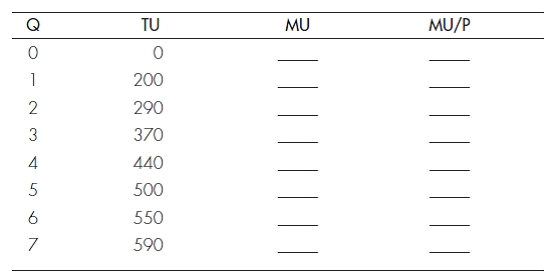

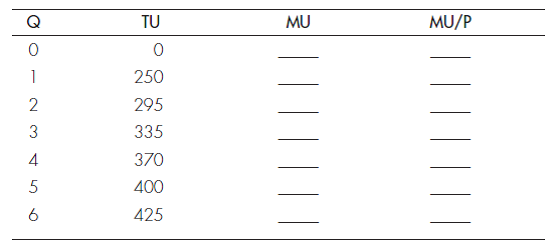

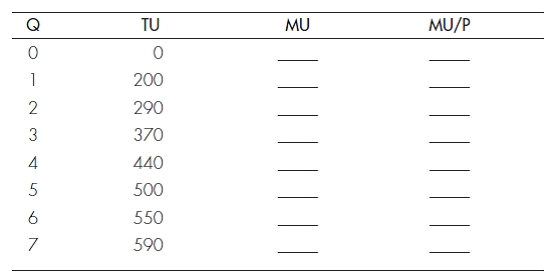

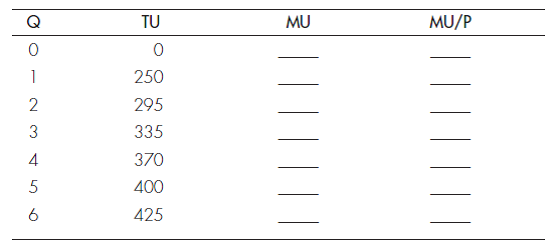

UTILITY MAXIMIZATION The following tables illustrate Eileen's utilities from watching first-run movies in a theater and from renting movies from a video store. Suppose that she has a monthly movie budget of $36, each movie ticket costs $6, and each video rental costs $3.

Movies in a Theater

Movies from a Video Store

a. Complete the tables.

b. Do these tables show that Eileen's preferences obey the law of diminishing marginal utility? Explain your answer.

c. How much of each good does Eileen consume in equilibrium?

d. Suppose the prices of both types of movies drop to $1 while Eileen's movie budget shrinks to $10. How much of each good does she consume in equilibrium?

Movies in a Theater

Movies from a Video Store

a. Complete the tables.

b. Do these tables show that Eileen's preferences obey the law of diminishing marginal utility? Explain your answer.

c. How much of each good does Eileen consume in equilibrium?

d. Suppose the prices of both types of movies drop to $1 while Eileen's movie budget shrinks to $10. How much of each good does she consume in equilibrium?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

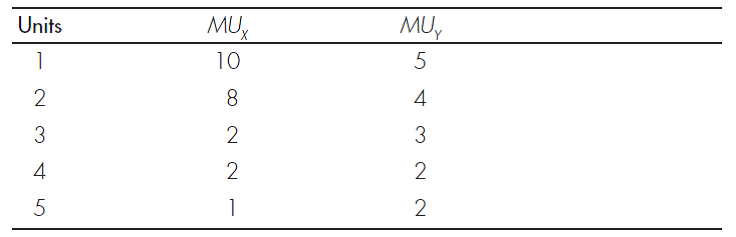

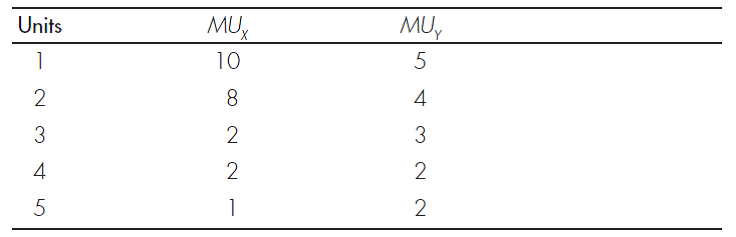

UTILITY MAXIMIZATION Suppose that a consumer has a choice between two goods, X and Y. If the price of X is $2 and the price of Y is $3, how much of X and Y does the consumer purchase, given an income of $17? Use the following information about marginal utilities:

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

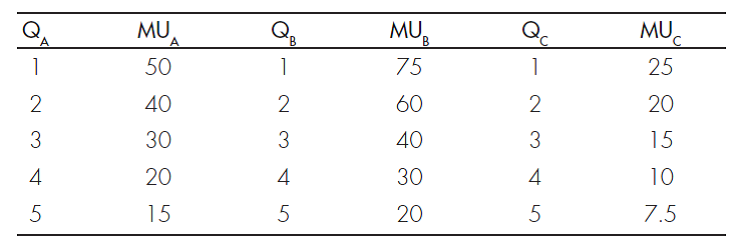

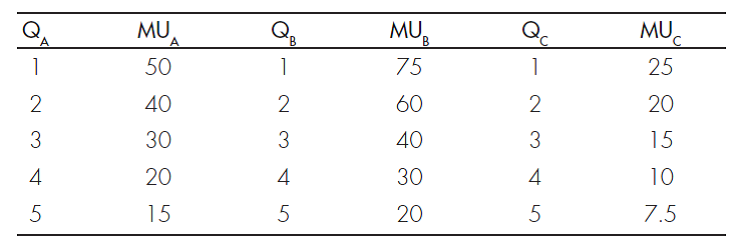

THE LAW OF DEMAND AND MARGINAL UTILITY Daniel allocates his budget of $24 per week among three goods. Use the following table of marginal utilities for good A , good B , and good C to answer the questions:

a. If the price of A is $2, the price of B is $3, and the price of C is $1, how much of each does Daniel purchase in equilibrium?

b. If the price of A rises to $4 while other prices and Daniel's budget remain unchanged, how much of each does he purchase in equilibrium?

c. Using the information from parts (a) and (b), draw the demand curve for good A. Be sure to indicate the price and quantity demanded for each point on the curve.

a. If the price of A is $2, the price of B is $3, and the price of C is $1, how much of each does Daniel purchase in equilibrium?

b. If the price of A rises to $4 while other prices and Daniel's budget remain unchanged, how much of each does he purchase in equilibrium?

c. Using the information from parts (a) and (b), draw the demand curve for good A. Be sure to indicate the price and quantity demanded for each point on the curve.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

CONSUMER SURPLUS Suppose the linear demand curve for shirts slopes downward and that consumers buy 500 shirts per year when the price is $30 and 1,000 shirts per year when the price is $25.

a. Compared to the prices of $30 and $25, what can you say about the marginal valuation that consumers place on the 300th shirt, the 700th shirt, and the 1,200th shirt they might buy each year?

b. With diminishing marginal utility, are consumers deriving any consumer surplus if the price is $25 per shirt? Explain.

c. Use a market demand curve to illustrate the change in consumer surplus if the price drops from $30 to $25.

a. Compared to the prices of $30 and $25, what can you say about the marginal valuation that consumers place on the 300th shirt, the 700th shirt, and the 1,200th shirt they might buy each year?

b. With diminishing marginal utility, are consumers deriving any consumer surplus if the price is $25 per shirt? Explain.

c. Use a market demand curve to illustrate the change in consumer surplus if the price drops from $30 to $25.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

Login to www.cengagebrain.com and access the Global Economic Watch to do this exercise.

Global Economic Watch Go to the Global Economic Crisis Resource Center. Select Global Issues in Context. In the Basic Search box at the top of the page, enter the phrase "applied economics." On the Results page, go to the Magazines section. Click on the link for the December 31, 2003, book review "How Economics Works." Think about the first paragraph of the book review. Do you expect to experience diminishing marginal utility in your economics course?

Global Economic Watch Go to the Global Economic Crisis Resource Center. Select Global Issues in Context. In the Basic Search box at the top of the page, enter the phrase "applied economics." On the Results page, go to the Magazines section. Click on the link for the December 31, 2003, book review "How Economics Works." Think about the first paragraph of the book review. Do you expect to experience diminishing marginal utility in your economics course?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

Login to www.cengagebrain.com and access the Global Economic Watch to do this exercise.

Global Economic Watch and Case Study: The Marginal Value of Free Medical Care Go to the Global Economic Crisis Resource Center. Select Global Issues in Context. Go to the menu at the top of the page and click on the tab for Browse Issues and Topics. Choose Health and Medicine. Click on the link for Access to Health Care. At the bottom of the Overview section, select View Full Overview. Read about access to health care in three categories of countries: developing nations, the United States, and industrialized nations with national health insurance systems. Describe the consumer surplus of the average citizen in each category of country.

Reference Case Study:

Public Policy

The Marginal Value of Free Medical Care Certain Americans, such as the elderly and those on welfare, receive government-subsidized medical care. State and federal taxpayers spend more than $750 billion a year providing medical care to 94 million Medicare and Medicaid recipients, or more than $8,000 per beneficiary. Medicaid is the largest and fastest growing spending category in most state budgets. Beneficiaries pay only a tiny share of Medicaid costs; most services are free.

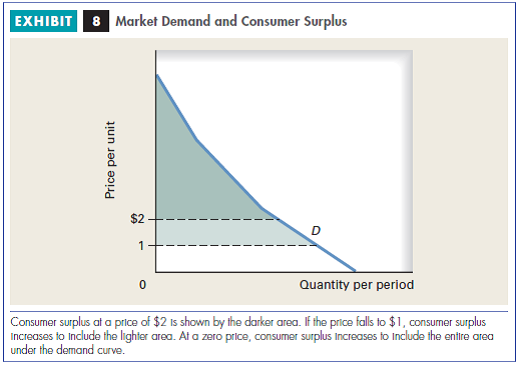

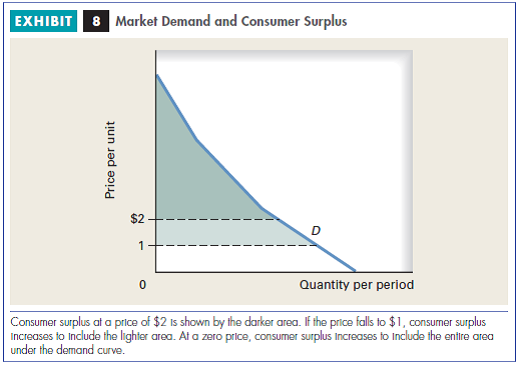

The problem with giving something away is that a beneficiary consumes it to the point where the marginal value reaches zero, although the marginal cost to taxpayers can be sizable. This is not to say that people derive no benefit from these programs. Although beneficiaries may attach little or no value to the final unit consumed, they likely derive a substantial consumer surplus from all the other units they consume. For example, suppose that Exhibit 8 represents the demand for health care by Medicaid beneficiaries. If the price they face is zero, each beneficiary consumes health care to the point where the demand curve intersects the horizontal axis-that is, where his or her marginal valuation is zero. Although they attach little or no value to their final unit of Medicaid-funded health care, their consumer surplus is the entire area under the demand curve.

One way to reduce the cost to taxpayers without significantly harming beneficiaries is to charge a token amount-say, $1 per doctor visit. Beneficiaries would eliminate visits they value less than $1. This practice would yield significant savings to taxpayers but would still leave beneficiaries with abundant health care and a substantial consumer surplus (measured in Exhibit 8 as the area under the demand curve but above the $1 price). As a case in point, one Medicaid experiment in California required some beneficiaries to pay $1 per visit for their first two office visits per month (after two visits, the price of additional visits reverted to zero). A control group continued to receive free medical care. The $1 charge reduced office visits by 8 percent compared to the control group. Medical care, like other goods and services, is also sensitive to its time cost (a topic discussed in the next section). For example, a 10 percent increase in the average travel time to a free outpatient clinic reduced visits by 10 percent. Similarly, when the relocation of a free health clinic at one college increased students' average walking time by 10 minutes, visits dropped 40 percent.

Another problem with giving something away is that beneficiaries are less vigilant about getting honest value, and this may increase the possibility of waste, fraud, and abuse. According to President Obama, "improper payments" for Medicaid and Medicare cost taxpayers nearly $100 billion in 2009. Medicaid fraud has replaced illegal drugs as the top crime in Florida. Crooks were charging the government for medical supplies that were not delivered or not needed (some supposed beneficiaries were dead). People won't tolerate padded bills and fake claims if they have to pay their own bills.

Finally, program beneficiaries have less incentive to pursue healthy behaviors themselves in their diet, their exercise, and the like. This doesn't necessarily mean certain groups don't deserve heavily subsidized medical care. The point is that when something is free, people consume it until their marginal value is zero, they pay less attention to getting honest value, and they take less personal responsibility for their own health.

Some Medicare beneficiaries visit one or more medical specialists most days of the week. Does all this medical attention improve their health care? Not according to a long running Dartmouth Medical School study. Researchers there found no apparent medical benefit and even some harm from such overuse. As one doctor lamented, "The system is broken. I'm not being a mean ogre, but when you give something away for free, there is nothing to keep utilization down." Even a modest money cost or time cost would reduce utilization, yet would still leave beneficiaries with quality health care and a substantial consumer surplus. Research suggests that up to 30 percent of all medical care is unnecessary.

Federal legislation in 2010 expanded the coverage of Medicaid and extended insurance coverage to many without it. Research by Michael Anderson and others suggests that one result will be a "substantial increase in care provided to currently uninsured individuals." No question, better health care can improve the quality of life, but overusing a service because the price is zero also wastes scarce resources.

Global Economic Watch and Case Study: The Marginal Value of Free Medical Care Go to the Global Economic Crisis Resource Center. Select Global Issues in Context. Go to the menu at the top of the page and click on the tab for Browse Issues and Topics. Choose Health and Medicine. Click on the link for Access to Health Care. At the bottom of the Overview section, select View Full Overview. Read about access to health care in three categories of countries: developing nations, the United States, and industrialized nations with national health insurance systems. Describe the consumer surplus of the average citizen in each category of country.

Reference Case Study:

Public Policy

The Marginal Value of Free Medical Care Certain Americans, such as the elderly and those on welfare, receive government-subsidized medical care. State and federal taxpayers spend more than $750 billion a year providing medical care to 94 million Medicare and Medicaid recipients, or more than $8,000 per beneficiary. Medicaid is the largest and fastest growing spending category in most state budgets. Beneficiaries pay only a tiny share of Medicaid costs; most services are free.

The problem with giving something away is that a beneficiary consumes it to the point where the marginal value reaches zero, although the marginal cost to taxpayers can be sizable. This is not to say that people derive no benefit from these programs. Although beneficiaries may attach little or no value to the final unit consumed, they likely derive a substantial consumer surplus from all the other units they consume. For example, suppose that Exhibit 8 represents the demand for health care by Medicaid beneficiaries. If the price they face is zero, each beneficiary consumes health care to the point where the demand curve intersects the horizontal axis-that is, where his or her marginal valuation is zero. Although they attach little or no value to their final unit of Medicaid-funded health care, their consumer surplus is the entire area under the demand curve.

One way to reduce the cost to taxpayers without significantly harming beneficiaries is to charge a token amount-say, $1 per doctor visit. Beneficiaries would eliminate visits they value less than $1. This practice would yield significant savings to taxpayers but would still leave beneficiaries with abundant health care and a substantial consumer surplus (measured in Exhibit 8 as the area under the demand curve but above the $1 price). As a case in point, one Medicaid experiment in California required some beneficiaries to pay $1 per visit for their first two office visits per month (after two visits, the price of additional visits reverted to zero). A control group continued to receive free medical care. The $1 charge reduced office visits by 8 percent compared to the control group. Medical care, like other goods and services, is also sensitive to its time cost (a topic discussed in the next section). For example, a 10 percent increase in the average travel time to a free outpatient clinic reduced visits by 10 percent. Similarly, when the relocation of a free health clinic at one college increased students' average walking time by 10 minutes, visits dropped 40 percent.

Another problem with giving something away is that beneficiaries are less vigilant about getting honest value, and this may increase the possibility of waste, fraud, and abuse. According to President Obama, "improper payments" for Medicaid and Medicare cost taxpayers nearly $100 billion in 2009. Medicaid fraud has replaced illegal drugs as the top crime in Florida. Crooks were charging the government for medical supplies that were not delivered or not needed (some supposed beneficiaries were dead). People won't tolerate padded bills and fake claims if they have to pay their own bills.

Finally, program beneficiaries have less incentive to pursue healthy behaviors themselves in their diet, their exercise, and the like. This doesn't necessarily mean certain groups don't deserve heavily subsidized medical care. The point is that when something is free, people consume it until their marginal value is zero, they pay less attention to getting honest value, and they take less personal responsibility for their own health.

Some Medicare beneficiaries visit one or more medical specialists most days of the week. Does all this medical attention improve their health care? Not according to a long running Dartmouth Medical School study. Researchers there found no apparent medical benefit and even some harm from such overuse. As one doctor lamented, "The system is broken. I'm not being a mean ogre, but when you give something away for free, there is nothing to keep utilization down." Even a modest money cost or time cost would reduce utilization, yet would still leave beneficiaries with quality health care and a substantial consumer surplus. Research suggests that up to 30 percent of all medical care is unnecessary.

Federal legislation in 2010 expanded the coverage of Medicaid and extended insurance coverage to many without it. Research by Michael Anderson and others suggests that one result will be a "substantial increase in care provided to currently uninsured individuals." No question, better health care can improve the quality of life, but overusing a service because the price is zero also wastes scarce resources.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

CONSUMER PREFERENCES The absolute value of the slope of the indifference curve equals the marginal rate of substitution. If two goods were perfect substitutes, what would the indifference curves look like? Explain.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

EFFECTS OF A CHANGE IN PRICE Chris has an income of $90 per month to allocate between Goods A and B. Initially the price of A is $3 and the price of B is $4.

a. Draw Chris's budget line, indicating its slope if units of A are measured on the horizontal axis and units of B are on the vertical axis.

b. Add an indifference curve to your graph and label the point of consumer equilibrium. Indicate Chris's consumption level of A and B. Explain why this is a consumer equilibrium. What can you say about Chris's total utility at this equilibrium?

c. Now suppose the price of A rises to $4. Draw the new budget line, a new point of equilibrium, and the consumption level of Goods A and B. What is Chris's marginal rate of substitution at the new equilibrium point?

d. Draw the demand curve for Good A, labeling the different price-quantity combinations determined in parts (b) and (c).

a. Draw Chris's budget line, indicating its slope if units of A are measured on the horizontal axis and units of B are on the vertical axis.

b. Add an indifference curve to your graph and label the point of consumer equilibrium. Indicate Chris's consumption level of A and B. Explain why this is a consumer equilibrium. What can you say about Chris's total utility at this equilibrium?

c. Now suppose the price of A rises to $4. Draw the new budget line, a new point of equilibrium, and the consumption level of Goods A and B. What is Chris's marginal rate of substitution at the new equilibrium point?

d. Draw the demand curve for Good A, labeling the different price-quantity combinations determined in parts (b) and (c).

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 19 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck