Deck 13: Leadership for Performance Excellence

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/30

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 13: Leadership for Performance Excellence

1

Alcoa, ranked as the 79th largest firm in the 2005 Fortune 500, employs approximately 129,000 people worldwide and had 2004 annual sales of $23.96 billion. Alcoa has been known for progressive, innovative management. It treats its employees well, tries to avoid layoffs and plant closures unless forced to make changes as a result of continued negative results, and has unions at only about 15 of its 47 locations. Nevertheless, at Alcoa's industrial magnesium plant in Addy, Washington, a crisis of epic proportions rocked the plant and rattled the company, leading to some key leadership changes that ultimately resulted in dramatic improvements in safety, productivity, and profits.

At the time of this case (in the late 1980s) the plant was facing two severe problems: an unacceptable rate of serious injuries that averaged 12.8 per year, and five years of unprofitable operations. No clear, easily-implemented solutions were apparent for the first problem, but corporate management had suggested that layoffs of 100 or more employees were all but inevitable in order to stem the tide of red ink. Operating statistics bore out the depth and breadth of the problem. Prices of magnesium had dropped, and units selling for $1.45 on the open market cost $1.48 to make at Alcoa's plant. Quality control was below what was needed to counteract market forces, with magnesium recovery at only 72 percent of the raw material being processed.

The apparent causes of plant problems consisted of a complex mix of lack of accountability, poor quality control, inadequate leadership, and low morale, especially among hourly employees. Corporate management stressed safety above all, and profitability second. The death of an employee, who was related to seven other employees, and the unacceptable financial losses led senior corporate management to decide that a change in plant management was essential. Don Simonic, a former college football coach, with Alcoa experience, was tapped for the job of plant manager. His turnaround team members included the then-personnel manager, Tom McCombs, and outside consultants Robert and Patricia Crosby. If the new leadership team could not turn the plant around, plant closure or sell-off were the only remaining options.

Since its construction, the plant had been designed with an open-systems, team-based culture, adapted from socio-technical systems theory. It was structured similar to the way that Procter and Gamble had set up its soap plants, and was considered a leading-edge organizational design. The process for producing the industrial magnesium was highly advanced and technical, and the innovative work team structure seemed to fit the technical systems characteristics. The plant attracted visitors from inside and outside the company who wanted to benchmark the operation and talk to team members. The organizational structure included:

• Autonomous, self-directed teams with no immediate supervisors. Teams were responsible for their own work areas.

• Hourly employee leadership that consisted of a team coordinator, safety person, training person, and team resource (internal facilitator) on each team.

• Supervisors, called shift coordinators, with four or five teams reporting to them, who were connected to the team coordinators. Shift coordinators generally stayed at arm's length, because if they intervened in team operations, they would get in trouble. The teams would say, "Leave us alone. We know what we're doing." If they didn't intervene, upper management would say that the teams weren't doing what they should be. The supervisors were caught in the middle.

Employees were empowered, but unable to face critical decisions that needed to be made to stem the crisis. The Crosbys identified lack of clarity in decision making and authority as the main culprit in the plant's environment. The new leadership model, conceived by the Crosbys and the plant leaders, involved major changes in goal-setting and decision-making practices. It required:

• New clarity in goal-setting.

• A consultative, instead of a pure consensus approach to decision making.

• Coming to grips with the need to cut costs pragmatically.

As the turnaround proceeded, Simonic decided that cutting staff was essential to meeting the new goals. First, all temporary and contract workers were laid off. As leaders were explaining the facts that had led to a decision to lay off an additional 100 workers, an hourly worker revealed a breakthrough that his team had made to significantly reduce the downtime required to turn a magnesium smelting furnace around. This process involved switching over to a new crucible once the other was filled (a form of the Japanese manufacturing technique called SMED-single minute exchange of dies). The new team approach required more labor, but cut the downtime from the usual one-and-a-half-hour turnaround time to just one hour. Simonic called off the impending layoffs. When the new process was implemented on all nine furnaces in the plant, the savings reached $10 million. This was more than the wages of the 100 employees, who were allowed to keep their jobs.

Simonic held strategic meetings where he engaged salaried and non-salaried employees in intensive dialogue. His objective was to align all parts of the system, clarify who would be making what decisions, explain how decisions could be influenced, and communicate why decisions were made. Simonic then set the goals. Simonic made clear statements like, "These are the goals. You and all our employees have firsthand knowledge of how things work around here. I don't care how you get there. I will support you in making choices about how to get there. And, if you can't get there, I will step in and decide how we will get there." McCombs, the personnel manager, remembered how they developed a matrix reflecting what kind of decisions team members and supervisors would make. Supervisors would still retain authority over all decisions, if needed. Before Simonic's arrival, decisions had been made largely by consensus.

As a result of this process, one person was made responsible for every project or task, known as singlepoint accountability. This proved to be a critical change that was used instead of the consensus (team) approach, which was previously the only way to perform projects. McCombs and Simonic believed that for single-point accountability to succeed, it was necessary to establish the "by whens"-when particular tasks would be accomplished. After making clear to the teams and employees what was expected, they started achieving goals better.

Eighteen months after Alcoa's brought Simonic in as plant manager, the change efforts had produced impressive results: Unit costs had been reduced from $ 1.48 to $1.18, recovery of magnesium increased by 5 percentage points (worth $1.3 million per point), and the serious-injury frequency fell from 12.8 to 6.3 per year. Although positive signs appeared throughout the process, the incident in which the layoffs were averted proved to be the most critical, because employees subsequently had taken responsibility for applying their own creativity to meeting plant goals. Over the next two years, the plant became the lowest-cost producer in the world, and shortly afterward had boosted productivity by 72 percent. The president of Alcoa even asked all of the plant managers to visit the site and learn from Addy's turnaround.

One decision-making technique that was practiced at Addy and several other Alcoa plants was consultative decision-making, where the manager makes the final decision but consults with the team first. For example, McCombs recalls an incident requiring disciplinary action on several teams: "The teams would have 24 hours to give their recommendations to management on how the discipline should be handled-up to and including termination- and management would administer the discipline. At least 95 percent of the time we took the team's recommendation and moved on," says McCombs.

The consultative method was also used to make hiring decisions. For example, the boundaries laid out for a team might concern Alcoa's desire to hire minorities. Typically, "the team would present their selection of who to hire to the manager, and often they would do such a good job the decision was just "'rubber-stamped,'" explains McCombs.

Another successful approach was called the "cadre." During the turnaround, Simonic and the Crosbys would work with the cadre, a group of key people, chosen from a vertical slice of the employees, who engaged in two specific roles: (1) observing and evaluating the change process as it played out while (2) simultaneously participating in the process. The cadre became a skilled resource for the plant on leadership development, change management, conflict management, quality, and work processes.

In reflecting on Simonic's impact on the organization, McCombs noted: "Don had a dynamic personality and was very charismatic. He possessed a very strong leadership style and was very clear. But you also must work with the intact families in the organization-one of Simonic's own beliefs. That's where change happens-in the small groups. You must work with that supervisor and that crew and get them aligned with the organization and work out any conflict." According to McCombs, Simonic was guided by four clear principles: "Leaders have to lead, make decisions, have a clear vision, and set direction. Once leaders set direction and get a breakthrough goal in mind that people can rally around, then people can tell the leader how they are going to get it done. A leader shouldn't tell how to do it, but he or she needs to set that direction. And that's what Simonic did very well," insists McCombs.

Unfortunately, Addy didn't sustain the momentum of the turnaround. In 1992, Simonic and McCombs left to help turn around other Alcoa plants. Corporate management continued to reduce the workforce. They eliminated all the department heads and everybody ended up reporting to the shift supervisor or plant manager. This caused lack of clarity about leadership and authority in decision making all over again, and as McCombs explained, "They stripped away the leadership that could have supported the change efforts afterwards."

Perhaps because of the previous successes and the skills gained in the previous turnaround, Crosby believed that the second recovery that occurred some time after Simonic and McCombs left was going to be much easier. The plant appeared to be back on track and headed for success again, but the fortunes of business intervened. There was another drop in the price of magnesium, and the Addy plant lost its competitive edge. In fall of 2001, the plant was closed down and approximately 350 employees lost their jobs.

How easy or difficult would it be for other organizations to duplicate the leadership style of Simonic and the organizational systems practiced at Addy, prior to, and after Simonic's tenure?

At the time of this case (in the late 1980s) the plant was facing two severe problems: an unacceptable rate of serious injuries that averaged 12.8 per year, and five years of unprofitable operations. No clear, easily-implemented solutions were apparent for the first problem, but corporate management had suggested that layoffs of 100 or more employees were all but inevitable in order to stem the tide of red ink. Operating statistics bore out the depth and breadth of the problem. Prices of magnesium had dropped, and units selling for $1.45 on the open market cost $1.48 to make at Alcoa's plant. Quality control was below what was needed to counteract market forces, with magnesium recovery at only 72 percent of the raw material being processed.

The apparent causes of plant problems consisted of a complex mix of lack of accountability, poor quality control, inadequate leadership, and low morale, especially among hourly employees. Corporate management stressed safety above all, and profitability second. The death of an employee, who was related to seven other employees, and the unacceptable financial losses led senior corporate management to decide that a change in plant management was essential. Don Simonic, a former college football coach, with Alcoa experience, was tapped for the job of plant manager. His turnaround team members included the then-personnel manager, Tom McCombs, and outside consultants Robert and Patricia Crosby. If the new leadership team could not turn the plant around, plant closure or sell-off were the only remaining options.

Since its construction, the plant had been designed with an open-systems, team-based culture, adapted from socio-technical systems theory. It was structured similar to the way that Procter and Gamble had set up its soap plants, and was considered a leading-edge organizational design. The process for producing the industrial magnesium was highly advanced and technical, and the innovative work team structure seemed to fit the technical systems characteristics. The plant attracted visitors from inside and outside the company who wanted to benchmark the operation and talk to team members. The organizational structure included:

• Autonomous, self-directed teams with no immediate supervisors. Teams were responsible for their own work areas.

• Hourly employee leadership that consisted of a team coordinator, safety person, training person, and team resource (internal facilitator) on each team.

• Supervisors, called shift coordinators, with four or five teams reporting to them, who were connected to the team coordinators. Shift coordinators generally stayed at arm's length, because if they intervened in team operations, they would get in trouble. The teams would say, "Leave us alone. We know what we're doing." If they didn't intervene, upper management would say that the teams weren't doing what they should be. The supervisors were caught in the middle.

Employees were empowered, but unable to face critical decisions that needed to be made to stem the crisis. The Crosbys identified lack of clarity in decision making and authority as the main culprit in the plant's environment. The new leadership model, conceived by the Crosbys and the plant leaders, involved major changes in goal-setting and decision-making practices. It required:

• New clarity in goal-setting.

• A consultative, instead of a pure consensus approach to decision making.

• Coming to grips with the need to cut costs pragmatically.

As the turnaround proceeded, Simonic decided that cutting staff was essential to meeting the new goals. First, all temporary and contract workers were laid off. As leaders were explaining the facts that had led to a decision to lay off an additional 100 workers, an hourly worker revealed a breakthrough that his team had made to significantly reduce the downtime required to turn a magnesium smelting furnace around. This process involved switching over to a new crucible once the other was filled (a form of the Japanese manufacturing technique called SMED-single minute exchange of dies). The new team approach required more labor, but cut the downtime from the usual one-and-a-half-hour turnaround time to just one hour. Simonic called off the impending layoffs. When the new process was implemented on all nine furnaces in the plant, the savings reached $10 million. This was more than the wages of the 100 employees, who were allowed to keep their jobs.

Simonic held strategic meetings where he engaged salaried and non-salaried employees in intensive dialogue. His objective was to align all parts of the system, clarify who would be making what decisions, explain how decisions could be influenced, and communicate why decisions were made. Simonic then set the goals. Simonic made clear statements like, "These are the goals. You and all our employees have firsthand knowledge of how things work around here. I don't care how you get there. I will support you in making choices about how to get there. And, if you can't get there, I will step in and decide how we will get there." McCombs, the personnel manager, remembered how they developed a matrix reflecting what kind of decisions team members and supervisors would make. Supervisors would still retain authority over all decisions, if needed. Before Simonic's arrival, decisions had been made largely by consensus.

As a result of this process, one person was made responsible for every project or task, known as singlepoint accountability. This proved to be a critical change that was used instead of the consensus (team) approach, which was previously the only way to perform projects. McCombs and Simonic believed that for single-point accountability to succeed, it was necessary to establish the "by whens"-when particular tasks would be accomplished. After making clear to the teams and employees what was expected, they started achieving goals better.

Eighteen months after Alcoa's brought Simonic in as plant manager, the change efforts had produced impressive results: Unit costs had been reduced from $ 1.48 to $1.18, recovery of magnesium increased by 5 percentage points (worth $1.3 million per point), and the serious-injury frequency fell from 12.8 to 6.3 per year. Although positive signs appeared throughout the process, the incident in which the layoffs were averted proved to be the most critical, because employees subsequently had taken responsibility for applying their own creativity to meeting plant goals. Over the next two years, the plant became the lowest-cost producer in the world, and shortly afterward had boosted productivity by 72 percent. The president of Alcoa even asked all of the plant managers to visit the site and learn from Addy's turnaround.

One decision-making technique that was practiced at Addy and several other Alcoa plants was consultative decision-making, where the manager makes the final decision but consults with the team first. For example, McCombs recalls an incident requiring disciplinary action on several teams: "The teams would have 24 hours to give their recommendations to management on how the discipline should be handled-up to and including termination- and management would administer the discipline. At least 95 percent of the time we took the team's recommendation and moved on," says McCombs.

The consultative method was also used to make hiring decisions. For example, the boundaries laid out for a team might concern Alcoa's desire to hire minorities. Typically, "the team would present their selection of who to hire to the manager, and often they would do such a good job the decision was just "'rubber-stamped,'" explains McCombs.

Another successful approach was called the "cadre." During the turnaround, Simonic and the Crosbys would work with the cadre, a group of key people, chosen from a vertical slice of the employees, who engaged in two specific roles: (1) observing and evaluating the change process as it played out while (2) simultaneously participating in the process. The cadre became a skilled resource for the plant on leadership development, change management, conflict management, quality, and work processes.

In reflecting on Simonic's impact on the organization, McCombs noted: "Don had a dynamic personality and was very charismatic. He possessed a very strong leadership style and was very clear. But you also must work with the intact families in the organization-one of Simonic's own beliefs. That's where change happens-in the small groups. You must work with that supervisor and that crew and get them aligned with the organization and work out any conflict." According to McCombs, Simonic was guided by four clear principles: "Leaders have to lead, make decisions, have a clear vision, and set direction. Once leaders set direction and get a breakthrough goal in mind that people can rally around, then people can tell the leader how they are going to get it done. A leader shouldn't tell how to do it, but he or she needs to set that direction. And that's what Simonic did very well," insists McCombs.

Unfortunately, Addy didn't sustain the momentum of the turnaround. In 1992, Simonic and McCombs left to help turn around other Alcoa plants. Corporate management continued to reduce the workforce. They eliminated all the department heads and everybody ended up reporting to the shift supervisor or plant manager. This caused lack of clarity about leadership and authority in decision making all over again, and as McCombs explained, "They stripped away the leadership that could have supported the change efforts afterwards."

Perhaps because of the previous successes and the skills gained in the previous turnaround, Crosby believed that the second recovery that occurred some time after Simonic and McCombs left was going to be much easier. The plant appeared to be back on track and headed for success again, but the fortunes of business intervened. There was another drop in the price of magnesium, and the Addy plant lost its competitive edge. In fall of 2001, the plant was closed down and approximately 350 employees lost their jobs.

How easy or difficult would it be for other organizations to duplicate the leadership style of Simonic and the organizational systems practiced at Addy, prior to, and after Simonic's tenure?

Facts:

The company A is a fortune 500 company and is one of the world's largest Magnesium extractor. The company started facing problems from injuries and increase in production expenses. The company identified a four men team to implement a change program and the company is considering of laying down people.

However, one of the part-time employees came up with a unique solution which can substantially reduce the downtime. Thus, helps in recovering the costs. The Four-member team avoided laying off people and implemented the solution and as a result, it saved nearly $10Million. In order to obtain the change, the team had decided to take centralized decision making and passing on the instructions to others.

Strategic Leadership:

Strategic leadership refers to the actions of visionary leaders who can change an organization's vision, mission and set clear-cut objectives for the organization to function. The decisions taken by such leaders will lead the firm to success and financial rewards both in the longer duration and the shorter duration. Strategic leaders play a vital role in defining the success of the organization by influencing others to take up challenges. They require excellent analytical skills, ability foresees changes and communication skills.

Discussion:

It will be a little bit difficult for the other organizations to implement the leadership styles followed by A Industry and S Hospitals. This is because the organizational structure and the management approach followed by both the organizations are based on socio-technical structure requiring team work and requiring a democratic approach.

Some of the important aspects of the structure are as follows:

1. The organization has adopted a standard operating procedure and guidelines which are innovative and different from others.

2. The management style adopted by the company is a free reign style of leadership style and employees are allowed to work freely without any supervision.

3. Customer influences : The influence of customers on the company also is an important factor to be considered by the Company.

4. Company Size: In this case, the large size of the company is a reason for the failure of the decentralized approach and it required a change.

5. Diversity in operations : The Company's varied operations also make it difficult for others to follow the same strategic management style.

6. Product Line : The Company'sproduct line is quite unique.Thus, it is quite difficult to follow this.

Thus, it can be concluded that other companies will find it somewhat difficult to follow the same style of leadership style adapted by A Industry.

The company A is a fortune 500 company and is one of the world's largest Magnesium extractor. The company started facing problems from injuries and increase in production expenses. The company identified a four men team to implement a change program and the company is considering of laying down people.

However, one of the part-time employees came up with a unique solution which can substantially reduce the downtime. Thus, helps in recovering the costs. The Four-member team avoided laying off people and implemented the solution and as a result, it saved nearly $10Million. In order to obtain the change, the team had decided to take centralized decision making and passing on the instructions to others.

Strategic Leadership:

Strategic leadership refers to the actions of visionary leaders who can change an organization's vision, mission and set clear-cut objectives for the organization to function. The decisions taken by such leaders will lead the firm to success and financial rewards both in the longer duration and the shorter duration. Strategic leaders play a vital role in defining the success of the organization by influencing others to take up challenges. They require excellent analytical skills, ability foresees changes and communication skills.

Discussion:

It will be a little bit difficult for the other organizations to implement the leadership styles followed by A Industry and S Hospitals. This is because the organizational structure and the management approach followed by both the organizations are based on socio-technical structure requiring team work and requiring a democratic approach.

Some of the important aspects of the structure are as follows:

1. The organization has adopted a standard operating procedure and guidelines which are innovative and different from others.

2. The management style adopted by the company is a free reign style of leadership style and employees are allowed to work freely without any supervision.

3. Customer influences : The influence of customers on the company also is an important factor to be considered by the Company.

4. Company Size: In this case, the large size of the company is a reason for the failure of the decentralized approach and it required a change.

5. Diversity in operations : The Company's varied operations also make it difficult for others to follow the same strategic management style.

6. Product Line : The Company'sproduct line is quite unique.Thus, it is quite difficult to follow this.

Thus, it can be concluded that other companies will find it somewhat difficult to follow the same style of leadership style adapted by A Industry.

2

Joseph Conklin proposes 10 questions for self-examination to help you understand your capacity for leadership. 42 Answer the following questions, and discuss why they are important for leadership.

a. How much do I like my job?

b. How often do I have to repeat myself?

c. How do I respond to failure?

d. How well do I put up with second guessing?

e. How early do I ask questions when making a decision?

f. How often do I say "thank you"?

g. Do I tend to favor a loose or strict interpretation of the rules?

h. Can I tell an obstacle from an excuse?

i. Is respect enough?

j. Have I dispensed with feeling indispensable?

a. How much do I like my job?

b. How often do I have to repeat myself?

c. How do I respond to failure?

d. How well do I put up with second guessing?

e. How early do I ask questions when making a decision?

f. How often do I say "thank you"?

g. Do I tend to favor a loose or strict interpretation of the rules?

h. Can I tell an obstacle from an excuse?

i. Is respect enough?

j. Have I dispensed with feeling indispensable?

Answers to JC's self-examination questions:

a. Mr. X loves his job the most. For him, job is primary and others are secondary.

b. Mostly Mr. X tries to complete his given target immediately as soon as he receives the work. He does not want to repeat it again and again.

c. Mr. X feels that failures are stepping stones to success.

d. Mr. X says that second guessing is not a good habit.

e. While making a decision Mr. X thinks twice and then raises questions.

f. "Thank You" is a magical word that pleases people according to Mr. X

g. Mr. X follows strict rules when the target is related to office work.

h. According to Mr. X, getting excuse for an incomplete work is an injustice done to organization.

i. Give respect, take respect.

j. Feeling vital source of an organization should motivate the worker to excel in given targets.

For a leadership quality, the above answers are very much essential as they provide all necessary details from starting point.

a. Mr. X loves his job the most. For him, job is primary and others are secondary.

b. Mostly Mr. X tries to complete his given target immediately as soon as he receives the work. He does not want to repeat it again and again.

c. Mr. X feels that failures are stepping stones to success.

d. Mr. X says that second guessing is not a good habit.

e. While making a decision Mr. X thinks twice and then raises questions.

f. "Thank You" is a magical word that pleases people according to Mr. X

g. Mr. X follows strict rules when the target is related to office work.

h. According to Mr. X, getting excuse for an incomplete work is an injustice done to organization.

i. Give respect, take respect.

j. Feeling vital source of an organization should motivate the worker to excel in given targets.

For a leadership quality, the above answers are very much essential as they provide all necessary details from starting point.

3

We emphasized that leadership is the "driver" of a total quality system. What does this statement imply and what implications does it have for future CEOs? Middle managers? Supervisors?

The statement "leadership is the driver of a total quality system" implies that for every successful step of an organization, leadership is the most essential part of quality management. The employees get motivated only with help of leader's advice. And it is the duty of leader to see that every employee gives his best.

An organization cannot survive if leaders are not working towards achieving a specific goal. Leaders and employees are the backbone of any organization or firm. Without strong commitment, total quality system may not survive or grow.

For future Chief Executive Officers, middle managers and supervisors, leadership quality acts as a driving tool to achieve something great. They are people who maintain the employees and try to get maximum work from them.

An organization cannot survive if leaders are not working towards achieving a specific goal. Leaders and employees are the backbone of any organization or firm. Without strong commitment, total quality system may not survive or grow.

For future Chief Executive Officers, middle managers and supervisors, leadership quality acts as a driving tool to achieve something great. They are people who maintain the employees and try to get maximum work from them.

4

Summarize the key leadership practices for performance excellence.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

Johnson Pharmaceuticals is a large manufacturer that was highly motivated to meet quality challenges. It implemented an ISO 9000-compatible quality system to ensure not only FDA compliance requirements, but also customer satisfaction. As the manufacturing plants of the organization were audited by the internal audit division, it became apparent that some plants were meeting the challenge, while others continued to struggle in both the quality and the regulatory aspects of production. This fact was evident in the reports of internal findings and in FDA inspection reports.

For the most part, the manufacturing plants share consistent resources and face similar environments. All were issued the responsibility of meeting the expectations of the quality system through the same mechanism. All understood the consequence of not conforming, that is, of jeopardizing their manufacturing license as bound by the consent decree. The issue then became why some plants could successfully design and implement the requirements of the quality system, whereas others could not and still cannot.

Although the plants are similar in many ways, they differ in terms of leadership, as each plant has its own CEO. The CEO, as the leader of his or her plant, has the responsibility of ensuring the successful implementation of a quality system. The plants also differ in their organizational members, those who are to be led by the CEO. The relationship between the leader and the organizational members is critical to a plant's ability to implement an effective quality system, with effectiveness being a measure of how successfully a plant can comply with FDA regulations and internal quality standards.

Both plants have a similar culture that can be best described as conserving, reflecting a level of rigidity in response to the external environment, but demonstrating organizational commitment. The strategy used by the leader in Plant A was a combination of moderate to high amounts of structuring actions, with high to moderate amounts of inspiring actions, whereas the strategy used by Plant B's CEO was a combination of moderate to low amounts of structuring actions, with moderate to high amounts of inspiring actions.

What type of situational leadership style did the CEO of each plant demonstrate?

For the most part, the manufacturing plants share consistent resources and face similar environments. All were issued the responsibility of meeting the expectations of the quality system through the same mechanism. All understood the consequence of not conforming, that is, of jeopardizing their manufacturing license as bound by the consent decree. The issue then became why some plants could successfully design and implement the requirements of the quality system, whereas others could not and still cannot.

Although the plants are similar in many ways, they differ in terms of leadership, as each plant has its own CEO. The CEO, as the leader of his or her plant, has the responsibility of ensuring the successful implementation of a quality system. The plants also differ in their organizational members, those who are to be led by the CEO. The relationship between the leader and the organizational members is critical to a plant's ability to implement an effective quality system, with effectiveness being a measure of how successfully a plant can comply with FDA regulations and internal quality standards.

Both plants have a similar culture that can be best described as conserving, reflecting a level of rigidity in response to the external environment, but demonstrating organizational commitment. The strategy used by the leader in Plant A was a combination of moderate to high amounts of structuring actions, with high to moderate amounts of inspiring actions, whereas the strategy used by Plant B's CEO was a combination of moderate to low amounts of structuring actions, with moderate to high amounts of inspiring actions.

What type of situational leadership style did the CEO of each plant demonstrate?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

State some examples in which leaders you have worked for exhibited some of the leading practices described in this chapter. Can you provide examples for which they have not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital (GSAM), a part of Advocate Health Care located in Downer's Grove, Illinois (a suburb of Chicago), is an acute-care medical facility that, since its opening in 1976, has grown from a mid-size community hospital to a nationally recognized leader in health care. However, it was not always nationally recognized. In 2004, Good Samaritan was true to its name-a "good," but not "great," hospital. Quality was generally perceived as good, but nursing care was seen as uneven; associate satisfaction was pretty good but not exceptional, physician satisfaction was mixed, and patient satisfaction was at best mediocre; technology and facilities were increasingly falling behind other hospitals; and it was struggling financially in a highly competitive market. Its leadership was determined to achieve, sustain, and redefine health care excellence, so it embarked on an organizational transformation to take the organization "from Good to Great (G2G)" The rationale for doing this was:

• To make good on its mission to be "a place of healing,"

• To create a framework for inspiring and integrating its efforts to build loyal relationships and provide great care, and

• To differentiate itself and ensure future success by becoming the best place for physicians to practice, associates to work, and patients to receive care.

The first steps that Good Samaritan took included

1. Establishing an inspiring vision: To provide an exceptional patient experience marked by superior health outcomes, service, and value.

2. Enrolling leaders in the vision.

3. Creating alignment, ownership, and transparency to support the vision. Quoting Ghandi, the president recognized that "you must be the change you want to see in the world." He recognized that transforming an organization cannot be delegated. Leadership needed to create a sense of urgency, explain the "why," and overcommunicate by a factor of 10.

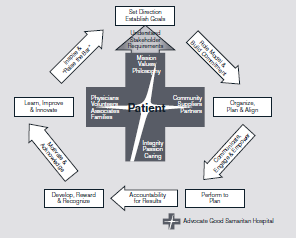

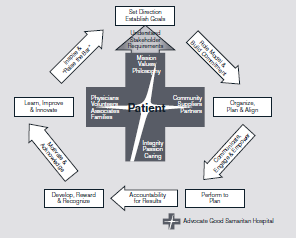

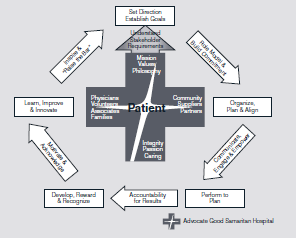

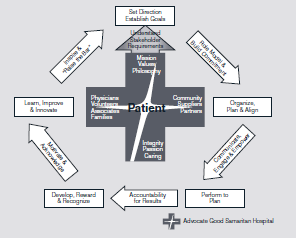

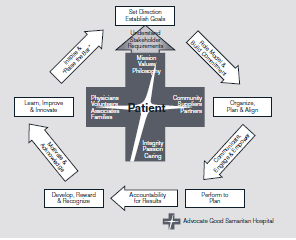

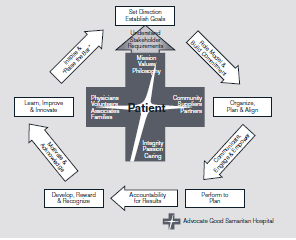

By 2006, the G2G journey had achieved some breakthrough results in patient satisfaction and clinical measures, and had spawned leading-edge innovations in health care. However, key questions remained: How would they ensure long-term sustainability? How would they create a legacy for the future? How could they hardwire best practices? How could they achieve repeatable excellence? Their response was to become a process-driven organization by embracing the Baldrige Criteria. The next major step was to establish a systematic leadership process, Good Samaritan Leadership System (GSLS), which is illustrated in Figure 13.2. The boxes represent the process steps, and the arrows represent the leadership behaviors needed to ensure that the steps are accomplished.

The GSLS ensures that all leaders at every level of the organization understand what is expected of them. Patients and stakeholders are at the center of the Leadership System. Driven by their Mission, Values, and Philosophy, all leaders must understand stakeholder requirements. At the organizational level, these requirements are determined in the Strategic Planning Process and used to set direction and establish and cascade goals. Action plans to achieve the goals are created, aligned, and communicated to engage the workforce. Goals and in-process measures are systematically reviewed and course corrections are made as necessary to ensure performance to plan. This focus on performance creates a rhythm of accountability and leads to subsequent associate development through the Capability Determination/Workforce Learning and Development System and reward and recognition of high performance. Development and recognition ensures that associates feel acknowledged and motivated. Stretch goals established in the SPP and a discomfort with the status quo prompts associates to learn, improve, and innovate through the Performance Improvement System. As leaders review annual performance, scan the environment, and recast organizational challenges, communication mechanisms are used to inspire and raise the bar.

FIGURE 13.2 Good Samaritan Leadership System

GSAM has a systematic eight-step governance process that cascades guidance from the Advocate Health Care Governing Board and Senior Leadership to the GSAM Governing Council/Senior Leadership Team and to all associates. Guidelines and procedures at all organizational levels ensure that the overall intent of governance is achieved and tracked through measures and goals. The process ensures transparency and equity for all stakeholders via Governing Council committee oversight, independent audits and through the diverse composition of the board. Annual review of metrics, the mission, vision and philosophy, and Standards of Behaviors ensures accountability and compliance.

GSAM also uses multiple stakeholder and community listening posts as inputs into the strategic planning process to address the societal well being of the community. GSAM considers environmental impact on the community. GSAM's Green Team implements multiple strategies to conserve energy and recycle materials to ensure protection of the environment. In keeping with their mission, GSAM also views societal well-being and community health as providing care for those without the ability to pay. In addition, GSAM actively participates in Access DuPage, an innovative community health approach through which GSAM primary care physicians and specialists provide care to the uninsured population, and GSAM provides all diagnostic tests and treatment without charge. Community fairs, screenings, immunizations, a hospital food pantry for associates, and financial/in-kind gifts also support environmental, social, and economic systems. GSAM contributes to improving their communities by all executive team members having multiple involvements on local boards; as well as the professional nursing staff, medical staff, and other members of the workforce actively participating in numerous service and professional organizations.

Market share has risen; patient satisfaction has exceeded the 90th percentile nationally for multiple segments, and physician and associate satisfaction reached the 97th percentile. The Delta Group ranked GSAM #1 in Illinois and #4 in the US for overall hospital care in 2010, one of 2011 's top 50 cardiovascular care hospitals by Thomson Reuters, and at the 100th percentile for patient safety by Thomson Reuters in 2010.

How does GSAM reflect the concept of strategic leadership?

• To make good on its mission to be "a place of healing,"

• To create a framework for inspiring and integrating its efforts to build loyal relationships and provide great care, and

• To differentiate itself and ensure future success by becoming the best place for physicians to practice, associates to work, and patients to receive care.

The first steps that Good Samaritan took included

1. Establishing an inspiring vision: To provide an exceptional patient experience marked by superior health outcomes, service, and value.

2. Enrolling leaders in the vision.

3. Creating alignment, ownership, and transparency to support the vision. Quoting Ghandi, the president recognized that "you must be the change you want to see in the world." He recognized that transforming an organization cannot be delegated. Leadership needed to create a sense of urgency, explain the "why," and overcommunicate by a factor of 10.

By 2006, the G2G journey had achieved some breakthrough results in patient satisfaction and clinical measures, and had spawned leading-edge innovations in health care. However, key questions remained: How would they ensure long-term sustainability? How would they create a legacy for the future? How could they hardwire best practices? How could they achieve repeatable excellence? Their response was to become a process-driven organization by embracing the Baldrige Criteria. The next major step was to establish a systematic leadership process, Good Samaritan Leadership System (GSLS), which is illustrated in Figure 13.2. The boxes represent the process steps, and the arrows represent the leadership behaviors needed to ensure that the steps are accomplished.

The GSLS ensures that all leaders at every level of the organization understand what is expected of them. Patients and stakeholders are at the center of the Leadership System. Driven by their Mission, Values, and Philosophy, all leaders must understand stakeholder requirements. At the organizational level, these requirements are determined in the Strategic Planning Process and used to set direction and establish and cascade goals. Action plans to achieve the goals are created, aligned, and communicated to engage the workforce. Goals and in-process measures are systematically reviewed and course corrections are made as necessary to ensure performance to plan. This focus on performance creates a rhythm of accountability and leads to subsequent associate development through the Capability Determination/Workforce Learning and Development System and reward and recognition of high performance. Development and recognition ensures that associates feel acknowledged and motivated. Stretch goals established in the SPP and a discomfort with the status quo prompts associates to learn, improve, and innovate through the Performance Improvement System. As leaders review annual performance, scan the environment, and recast organizational challenges, communication mechanisms are used to inspire and raise the bar.

FIGURE 13.2 Good Samaritan Leadership System

GSAM has a systematic eight-step governance process that cascades guidance from the Advocate Health Care Governing Board and Senior Leadership to the GSAM Governing Council/Senior Leadership Team and to all associates. Guidelines and procedures at all organizational levels ensure that the overall intent of governance is achieved and tracked through measures and goals. The process ensures transparency and equity for all stakeholders via Governing Council committee oversight, independent audits and through the diverse composition of the board. Annual review of metrics, the mission, vision and philosophy, and Standards of Behaviors ensures accountability and compliance.

GSAM also uses multiple stakeholder and community listening posts as inputs into the strategic planning process to address the societal well being of the community. GSAM considers environmental impact on the community. GSAM's Green Team implements multiple strategies to conserve energy and recycle materials to ensure protection of the environment. In keeping with their mission, GSAM also views societal well-being and community health as providing care for those without the ability to pay. In addition, GSAM actively participates in Access DuPage, an innovative community health approach through which GSAM primary care physicians and specialists provide care to the uninsured population, and GSAM provides all diagnostic tests and treatment without charge. Community fairs, screenings, immunizations, a hospital food pantry for associates, and financial/in-kind gifts also support environmental, social, and economic systems. GSAM contributes to improving their communities by all executive team members having multiple involvements on local boards; as well as the professional nursing staff, medical staff, and other members of the workforce actively participating in numerous service and professional organizations.

Market share has risen; patient satisfaction has exceeded the 90th percentile nationally for multiple segments, and physician and associate satisfaction reached the 97th percentile. The Delta Group ranked GSAM #1 in Illinois and #4 in the US for overall hospital care in 2010, one of 2011 's top 50 cardiovascular care hospitals by Thomson Reuters, and at the 100th percentile for patient safety by Thomson Reuters in 2010.

How does GSAM reflect the concept of strategic leadership?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Conduct some research to explain the traditional theories of leadership in Table 13.2 and their implications for quality and performance excellence.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Alcoa, ranked as the 79th largest firm in the 2005 Fortune 500, employs approximately 129,000 people worldwide and had 2004 annual sales of $23.96 billion. Alcoa has been known for progressive, innovative management. It treats its employees well, tries to avoid layoffs and plant closures unless forced to make changes as a result of continued negative results, and has unions at only about 15 of its 47 locations. Nevertheless, at Alcoa's industrial magnesium plant in Addy, Washington, a crisis of epic proportions rocked the plant and rattled the company, leading to some key leadership changes that ultimately resulted in dramatic improvements in safety, productivity, and profits.

At the time of this case (in the late 1980s) the plant was facing two severe problems: an unacceptable rate of serious injuries that averaged 12.8 per year, and five years of unprofitable operations. No clear, easily-implemented solutions were apparent for the first problem, but corporate management had suggested that layoffs of 100 or more employees were all but inevitable in order to stem the tide of red ink. Operating statistics bore out the depth and breadth of the problem. Prices of magnesium had dropped, and units selling for $1.45 on the open market cost $1.48 to make at Alcoa's plant. Quality control was below what was needed to counteract market forces, with magnesium recovery at only 72 percent of the raw material being processed.

The apparent causes of plant problems consisted of a complex mix of lack of accountability, poor quality control, inadequate leadership, and low morale, especially among hourly employees. Corporate management stressed safety above all, and profitability second. The death of an employee, who was related to seven other employees, and the unacceptable financial losses led senior corporate management to decide that a change in plant management was essential. Don Simonic, a former college football coach, with Alcoa experience, was tapped for the job of plant manager. His turnaround team members included the then-personnel manager, Tom McCombs, and outside consultants Robert and Patricia Crosby. If the new leadership team could not turn the plant around, plant closure or sell-off were the only remaining options.

Since its construction, the plant had been designed with an open-systems, team-based culture, adapted from socio-technical systems theory. It was structured similar to the way that Procter and Gamble had set up its soap plants, and was considered a leading-edge organizational design. The process for producing the industrial magnesium was highly advanced and technical, and the innovative work team structure seemed to fit the technical systems characteristics. The plant attracted visitors from inside and outside the company who wanted to benchmark the operation and talk to team members. The organizational structure included:

• Autonomous, self-directed teams with no immediate supervisors. Teams were responsible for their own work areas.

• Hourly employee leadership that consisted of a team coordinator, safety person, training person, and team resource (internal facilitator) on each team.

• Supervisors, called shift coordinators, with four or five teams reporting to them, who were connected to the team coordinators. Shift coordinators generally stayed at arm's length, because if they intervened in team operations, they would get in trouble. The teams would say, "Leave us alone. We know what we're doing." If they didn't intervene, upper management would say that the teams weren't doing what they should be. The supervisors were caught in the middle.

Employees were empowered, but unable to face critical decisions that needed to be made to stem the crisis. The Crosbys identified lack of clarity in decision making and authority as the main culprit in the plant's environment. The new leadership model, conceived by the Crosbys and the plant leaders, involved major changes in goal-setting and decision-making practices. It required:

• New clarity in goal-setting.

• A consultative, instead of a pure consensus approach to decision making.

• Coming to grips with the need to cut costs pragmatically.

As the turnaround proceeded, Simonic decided that cutting staff was essential to meeting the new goals. First, all temporary and contract workers were laid off. As leaders were explaining the facts that had led to a decision to lay off an additional 100 workers, an hourly worker revealed a breakthrough that his team had made to significantly reduce the downtime required to turn a magnesium smelting furnace around. This process involved switching over to a new crucible once the other was filled (a form of the Japanese manufacturing technique called SMED-single minute exchange of dies). The new team approach required more labor, but cut the downtime from the usual one-and-a-half-hour turnaround time to just one hour. Simonic called off the impending layoffs. When the new process was implemented on all nine furnaces in the plant, the savings reached $10 million. This was more than the wages of the 100 employees, who were allowed to keep their jobs.

Simonic held strategic meetings where he engaged salaried and non-salaried employees in intensive dialogue. His objective was to align all parts of the system, clarify who would be making what decisions, explain how decisions could be influenced, and communicate why decisions were made. Simonic then set the goals. Simonic made clear statements like, "These are the goals. You and all our employees have firsthand knowledge of how things work around here. I don't care how you get there. I will support you in making choices about how to get there. And, if you can't get there, I will step in and decide how we will get there." McCombs, the personnel manager, remembered how they developed a matrix reflecting what kind of decisions team members and supervisors would make. Supervisors would still retain authority over all decisions, if needed. Before Simonic's arrival, decisions had been made largely by consensus.

As a result of this process, one person was made responsible for every project or task, known as singlepoint accountability. This proved to be a critical change that was used instead of the consensus (team) approach, which was previously the only way to perform projects. McCombs and Simonic believed that for single-point accountability to succeed, it was necessary to establish the "by whens"-when particular tasks would be accomplished. After making clear to the teams and employees what was expected, they started achieving goals better.

Eighteen months after Alcoa's brought Simonic in as plant manager, the change efforts had produced impressive results: Unit costs had been reduced from $ 1.48 to $1.18, recovery of magnesium increased by 5 percentage points (worth $1.3 million per point), and the serious-injury frequency fell from 12.8 to 6.3 per year. Although positive signs appeared throughout the process, the incident in which the layoffs were averted proved to be the most critical, because employees subsequently had taken responsibility for applying their own creativity to meeting plant goals. Over the next two years, the plant became the lowest-cost producer in the world, and shortly afterward had boosted productivity by 72 percent. The president of Alcoa even asked all of the plant managers to visit the site and learn from Addy's turnaround.

One decision-making technique that was practiced at Addy and several other Alcoa plants was consultative decision-making, where the manager makes the final decision but consults with the team first. For example, McCombs recalls an incident requiring disciplinary action on several teams: "The teams would have 24 hours to give their recommendations to management on how the discipline should be handled-up to and including termination- and management would administer the discipline. At least 95 percent of the time we took the team's recommendation and moved on," says McCombs.

The consultative method was also used to make hiring decisions. For example, the boundaries laid out for a team might concern Alcoa's desire to hire minorities. Typically, "the team would present their selection of who to hire to the manager, and often they would do such a good job the decision was just "'rubber-stamped,'" explains McCombs.

Another successful approach was called the "cadre." During the turnaround, Simonic and the Crosbys would work with the cadre, a group of key people, chosen from a vertical slice of the employees, who engaged in two specific roles: (1) observing and evaluating the change process as it played out while (2) simultaneously participating in the process. The cadre became a skilled resource for the plant on leadership development, change management, conflict management, quality, and work processes.

In reflecting on Simonic's impact on the organization, McCombs noted: "Don had a dynamic personality and was very charismatic. He possessed a very strong leadership style and was very clear. But you also must work with the intact families in the organization-one of Simonic's own beliefs. That's where change happens-in the small groups. You must work with that supervisor and that crew and get them aligned with the organization and work out any conflict." According to McCombs, Simonic was guided by four clear principles: "Leaders have to lead, make decisions, have a clear vision, and set direction. Once leaders set direction and get a breakthrough goal in mind that people can rally around, then people can tell the leader how they are going to get it done. A leader shouldn't tell how to do it, but he or she needs to set that direction. And that's what Simonic did very well," insists McCombs.

Unfortunately, Addy didn't sustain the momentum of the turnaround. In 1992, Simonic and McCombs left to help turn around other Alcoa plants. Corporate management continued to reduce the workforce. They eliminated all the department heads and everybody ended up reporting to the shift supervisor or plant manager. This caused lack of clarity about leadership and authority in decision making all over again, and as McCombs explained, "They stripped away the leadership that could have supported the change efforts afterwards."

Perhaps because of the previous successes and the skills gained in the previous turnaround, Crosby believed that the second recovery that occurred some time after Simonic and McCombs left was going to be much easier. The plant appeared to be back on track and headed for success again, but the fortunes of business intervened. There was another drop in the price of magnesium, and the Addy plant lost its competitive edge. In fall of 2001, the plant was closed down and approximately 350 employees lost their jobs.

From a strategic management standpoint, why do you think that corporate management at Alcoa delayed taking action for five years as the plant continued to lose money and deteriorate in other operational measures?

At the time of this case (in the late 1980s) the plant was facing two severe problems: an unacceptable rate of serious injuries that averaged 12.8 per year, and five years of unprofitable operations. No clear, easily-implemented solutions were apparent for the first problem, but corporate management had suggested that layoffs of 100 or more employees were all but inevitable in order to stem the tide of red ink. Operating statistics bore out the depth and breadth of the problem. Prices of magnesium had dropped, and units selling for $1.45 on the open market cost $1.48 to make at Alcoa's plant. Quality control was below what was needed to counteract market forces, with magnesium recovery at only 72 percent of the raw material being processed.

The apparent causes of plant problems consisted of a complex mix of lack of accountability, poor quality control, inadequate leadership, and low morale, especially among hourly employees. Corporate management stressed safety above all, and profitability second. The death of an employee, who was related to seven other employees, and the unacceptable financial losses led senior corporate management to decide that a change in plant management was essential. Don Simonic, a former college football coach, with Alcoa experience, was tapped for the job of plant manager. His turnaround team members included the then-personnel manager, Tom McCombs, and outside consultants Robert and Patricia Crosby. If the new leadership team could not turn the plant around, plant closure or sell-off were the only remaining options.

Since its construction, the plant had been designed with an open-systems, team-based culture, adapted from socio-technical systems theory. It was structured similar to the way that Procter and Gamble had set up its soap plants, and was considered a leading-edge organizational design. The process for producing the industrial magnesium was highly advanced and technical, and the innovative work team structure seemed to fit the technical systems characteristics. The plant attracted visitors from inside and outside the company who wanted to benchmark the operation and talk to team members. The organizational structure included:

• Autonomous, self-directed teams with no immediate supervisors. Teams were responsible for their own work areas.

• Hourly employee leadership that consisted of a team coordinator, safety person, training person, and team resource (internal facilitator) on each team.

• Supervisors, called shift coordinators, with four or five teams reporting to them, who were connected to the team coordinators. Shift coordinators generally stayed at arm's length, because if they intervened in team operations, they would get in trouble. The teams would say, "Leave us alone. We know what we're doing." If they didn't intervene, upper management would say that the teams weren't doing what they should be. The supervisors were caught in the middle.

Employees were empowered, but unable to face critical decisions that needed to be made to stem the crisis. The Crosbys identified lack of clarity in decision making and authority as the main culprit in the plant's environment. The new leadership model, conceived by the Crosbys and the plant leaders, involved major changes in goal-setting and decision-making practices. It required:

• New clarity in goal-setting.

• A consultative, instead of a pure consensus approach to decision making.

• Coming to grips with the need to cut costs pragmatically.

As the turnaround proceeded, Simonic decided that cutting staff was essential to meeting the new goals. First, all temporary and contract workers were laid off. As leaders were explaining the facts that had led to a decision to lay off an additional 100 workers, an hourly worker revealed a breakthrough that his team had made to significantly reduce the downtime required to turn a magnesium smelting furnace around. This process involved switching over to a new crucible once the other was filled (a form of the Japanese manufacturing technique called SMED-single minute exchange of dies). The new team approach required more labor, but cut the downtime from the usual one-and-a-half-hour turnaround time to just one hour. Simonic called off the impending layoffs. When the new process was implemented on all nine furnaces in the plant, the savings reached $10 million. This was more than the wages of the 100 employees, who were allowed to keep their jobs.

Simonic held strategic meetings where he engaged salaried and non-salaried employees in intensive dialogue. His objective was to align all parts of the system, clarify who would be making what decisions, explain how decisions could be influenced, and communicate why decisions were made. Simonic then set the goals. Simonic made clear statements like, "These are the goals. You and all our employees have firsthand knowledge of how things work around here. I don't care how you get there. I will support you in making choices about how to get there. And, if you can't get there, I will step in and decide how we will get there." McCombs, the personnel manager, remembered how they developed a matrix reflecting what kind of decisions team members and supervisors would make. Supervisors would still retain authority over all decisions, if needed. Before Simonic's arrival, decisions had been made largely by consensus.

As a result of this process, one person was made responsible for every project or task, known as singlepoint accountability. This proved to be a critical change that was used instead of the consensus (team) approach, which was previously the only way to perform projects. McCombs and Simonic believed that for single-point accountability to succeed, it was necessary to establish the "by whens"-when particular tasks would be accomplished. After making clear to the teams and employees what was expected, they started achieving goals better.

Eighteen months after Alcoa's brought Simonic in as plant manager, the change efforts had produced impressive results: Unit costs had been reduced from $ 1.48 to $1.18, recovery of magnesium increased by 5 percentage points (worth $1.3 million per point), and the serious-injury frequency fell from 12.8 to 6.3 per year. Although positive signs appeared throughout the process, the incident in which the layoffs were averted proved to be the most critical, because employees subsequently had taken responsibility for applying their own creativity to meeting plant goals. Over the next two years, the plant became the lowest-cost producer in the world, and shortly afterward had boosted productivity by 72 percent. The president of Alcoa even asked all of the plant managers to visit the site and learn from Addy's turnaround.

One decision-making technique that was practiced at Addy and several other Alcoa plants was consultative decision-making, where the manager makes the final decision but consults with the team first. For example, McCombs recalls an incident requiring disciplinary action on several teams: "The teams would have 24 hours to give their recommendations to management on how the discipline should be handled-up to and including termination- and management would administer the discipline. At least 95 percent of the time we took the team's recommendation and moved on," says McCombs.

The consultative method was also used to make hiring decisions. For example, the boundaries laid out for a team might concern Alcoa's desire to hire minorities. Typically, "the team would present their selection of who to hire to the manager, and often they would do such a good job the decision was just "'rubber-stamped,'" explains McCombs.

Another successful approach was called the "cadre." During the turnaround, Simonic and the Crosbys would work with the cadre, a group of key people, chosen from a vertical slice of the employees, who engaged in two specific roles: (1) observing and evaluating the change process as it played out while (2) simultaneously participating in the process. The cadre became a skilled resource for the plant on leadership development, change management, conflict management, quality, and work processes.

In reflecting on Simonic's impact on the organization, McCombs noted: "Don had a dynamic personality and was very charismatic. He possessed a very strong leadership style and was very clear. But you also must work with the intact families in the organization-one of Simonic's own beliefs. That's where change happens-in the small groups. You must work with that supervisor and that crew and get them aligned with the organization and work out any conflict." According to McCombs, Simonic was guided by four clear principles: "Leaders have to lead, make decisions, have a clear vision, and set direction. Once leaders set direction and get a breakthrough goal in mind that people can rally around, then people can tell the leader how they are going to get it done. A leader shouldn't tell how to do it, but he or she needs to set that direction. And that's what Simonic did very well," insists McCombs.

Unfortunately, Addy didn't sustain the momentum of the turnaround. In 1992, Simonic and McCombs left to help turn around other Alcoa plants. Corporate management continued to reduce the workforce. They eliminated all the department heads and everybody ended up reporting to the shift supervisor or plant manager. This caused lack of clarity about leadership and authority in decision making all over again, and as McCombs explained, "They stripped away the leadership that could have supported the change efforts afterwards."

Perhaps because of the previous successes and the skills gained in the previous turnaround, Crosby believed that the second recovery that occurred some time after Simonic and McCombs left was going to be much easier. The plant appeared to be back on track and headed for success again, but the fortunes of business intervened. There was another drop in the price of magnesium, and the Addy plant lost its competitive edge. In fall of 2001, the plant was closed down and approximately 350 employees lost their jobs.

From a strategic management standpoint, why do you think that corporate management at Alcoa delayed taking action for five years as the plant continued to lose money and deteriorate in other operational measures?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

What is strategic leadership? How does it differ from the common concept of leadership?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

Using the information in this chapter, design a questionnaire that might be used to understand leadership effectiveness in an organization.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

You have undoubtedly seen a flock of geese flying overhead. How do the following behaviors of this species provide insight about leadership?

a. As each bird flaps its wings, it creates uplift for the bird behind. By using a "V" formation, the whole flock adds 71 percent more flying range than if each bird flew alone.

b. Whenever one falls out of formation, it suddenly feels the resistance of trying to fly alone, and quickly gets back into formation to take advantage of the lifting power of the birds immediately in front.

c. When the lead bird gets tired, it rotates back into formation and another flies at the point position.

d. The birds in formation honk from behind to encourage those up front to maintain their speed.

e. When one gets sick or wounded or shot down, two birds drop out of formation and follow their fellow member down to help or provide protection. They stay with this member of the flock until it can fly again or dies. Then they launch out on their own, with another formation or to catch up with their own flock.

a. As each bird flaps its wings, it creates uplift for the bird behind. By using a "V" formation, the whole flock adds 71 percent more flying range than if each bird flew alone.

b. Whenever one falls out of formation, it suddenly feels the resistance of trying to fly alone, and quickly gets back into formation to take advantage of the lifting power of the birds immediately in front.

c. When the lead bird gets tired, it rotates back into formation and another flies at the point position.

d. The birds in formation honk from behind to encourage those up front to maintain their speed.

e. When one gets sick or wounded or shot down, two birds drop out of formation and follow their fellow member down to help or provide protection. They stay with this member of the flock until it can fly again or dies. Then they launch out on their own, with another formation or to catch up with their own flock.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Define leadership. Why is it necessary for a culture of performance excellence?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

Explain the concept of a leadership system. What elements should an effective leadership system have?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

At Ablecor, Inc., senior management announced a restructuring/reorganization plan every January, with a target completion date of June. The reorganization directives mentioned strategic objectives and the competitive environment, but this changed very little from year to year. There were no announcements from leadership on what was to be accomplished by the reorganization, nor were any process changes explained. In addition, there was no effort to get the workforce involved in new initiatives. At the end of the day, nothing ever changed from these reorganizations, just a shuffling of managers and departments to justify reducing staff. First-line managers, middle managers, and junior executives throughout the company spent the year dreading the reorganization, sweating through the process wondering if this was the year their job was to be eliminated, and then being thankful that they were spared for one more year. The economy was down, so it was difficult to leave and take a job elsewhere. Except for a few critical positions, there was little training or management development for those employees with new responsibilities. Customers were often confused and frustrated by having to deal with a succession of new or "re-shuffled" contact people each year.

At Baycor, Ltd., one department was asked by senior leadership to develop action plans and projects needed to launch a new product. The department manager took the initiative to implement a transformational change and appointed a lead team consisting of her section managers and a few key subject-matter experts. As the employees became more inspired by the thoughts and ideas surrounding the transformation, the lead team became aware that their power base was going to disappear if the changes were actually implemented, especially if employees were empowered to recommend changes and make some decisions on their own. The lead team decided implicitly and explicitly not to allow any significant changes to occur. After four months of anticipation by supervisors and employees, the lead team just declared the transformation finished and went back to business as usual. This was frustrating and demoralizing to the employees.

Discuss how the leadership failed to foster change in order to create a sustainable organizational structure and environment at Ablecor.

At Baycor, Ltd., one department was asked by senior leadership to develop action plans and projects needed to launch a new product. The department manager took the initiative to implement a transformational change and appointed a lead team consisting of her section managers and a few key subject-matter experts. As the employees became more inspired by the thoughts and ideas surrounding the transformation, the lead team became aware that their power base was going to disappear if the changes were actually implemented, especially if employees were empowered to recommend changes and make some decisions on their own. The lead team decided implicitly and explicitly not to allow any significant changes to occur. After four months of anticipation by supervisors and employees, the lead team just declared the transformation finished and went back to business as usual. This was frustrating and demoralizing to the employees.

Discuss how the leadership failed to foster change in order to create a sustainable organizational structure and environment at Ablecor.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

What is the role of steering teams in many leadership systems?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

Provide examples from your own experiences in which leaders (not necessarily managers-consider academic unit heads, presidents of student organizations, and even family members) exhibited one or more of the six key leadership competencies described in this chapter. What impacts did these competencies have on the organization?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

How do emerging leadership theories differ from traditional theories? Summarize them and their importance in leadership for performance excellence.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

Advocate Good Samaritan Hospital (GSAM), a part of Advocate Health Care located in Downer's Grove, Illinois (a suburb of Chicago), is an acute-care medical facility that, since its opening in 1976, has grown from a mid-size community hospital to a nationally recognized leader in health care. However, it was not always nationally recognized. In 2004, Good Samaritan was true to its name-a "good," but not "great," hospital. Quality was generally perceived as good, but nursing care was seen as uneven; associate satisfaction was pretty good but not exceptional, physician satisfaction was mixed, and patient satisfaction was at best mediocre; technology and facilities were increasingly falling behind other hospitals; and it was struggling financially in a highly competitive market. Its leadership was determined to achieve, sustain, and redefine health care excellence, so it embarked on an organizational transformation to take the organization "from Good to Great (G2G)" The rationale for doing this was:

• To make good on its mission to be "a place of healing,"

• To create a framework for inspiring and integrating its efforts to build loyal relationships and provide great care, and

• To differentiate itself and ensure future success by becoming the best place for physicians to practice, associates to work, and patients to receive care.

The first steps that Good Samaritan took included