Deck 3: Planning and Strategic Management

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/30

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 3: Planning and Strategic Management

1

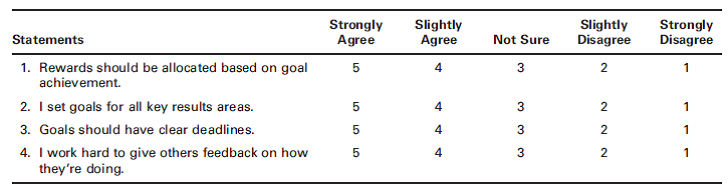

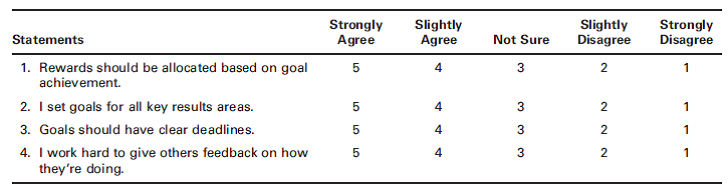

Goal-Setting Questionnaire

This exercise will help you understand how to conceptualize the elements of goal setting and your own goalsetting tendencies.

Instructions: Indicate your concepts of your goalsetting behaviors and feelings by circling the appropriate number on the scale for each statement.

This exercise will help you understand how to conceptualize the elements of goal setting and your own goalsetting tendencies.

Instructions: Indicate your concepts of your goalsetting behaviors and feelings by circling the appropriate number on the scale for each statement.

Gola setting is a process that establishes definite, quantifiable, accurate, attainable and targeted goals for an individual or an organization.

The aim of this goal is to ensure that participants in a set group are clearly informed about your respective duties.

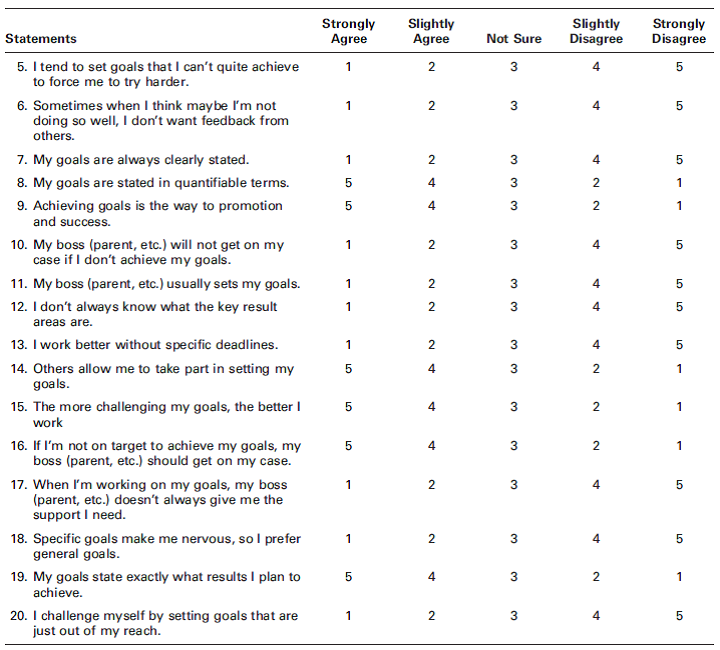

The below mentioned scores would enable the person to evaluate the status of the goal. The higher the scores, the closer the person would have goal-setting behaviors.

The stated statements are scored in the following way:

Statements Score

• Rewards should be allocated based on goal achievements 5

• I set goals for all key result areas 2

• Goals should have clear deadlines 5

• I work hard to give others feedback on how they are doing 4

• I tend to set goals that I can't quite achieve to force me to try

harder. 4

• Sometimes when I think maybe I'm not doing so well

I don't want feedback from others. 4

• My goals are always clearly stated 3

• My goals are stated in quantifiable terms 3

• Achieving goals is the way to promotion and success. 5

• My boss will not get on my case if I don't want them to. 1

• My boss usually sets my goals 5

• I don't always know what are my key result areas 3

• I work better without specific deadlines. 1

• Others allow me to take part in setting my goals. 4

• The more challenging my goals the better I work. 5

• If I'm not on target to achieve my goals my boss should get on

my case.

• When I 'm working on my goals, my boss doesn't always

give me the support I need. 4

• Specific goals make me nervous so I prefer general goals. 1

• My goals state exactly what results I plan to achieve. 2

• I challenge myself by setting goals that are just out of my reach. 5

Hence, the total Score comes out to be 70. This score is pretty closer to 100 and one can conclude that the person has achieved the goal setting behavior to some extent. However, every person has their own set of views and hence would score the statements differently.

The aim of this goal is to ensure that participants in a set group are clearly informed about your respective duties.

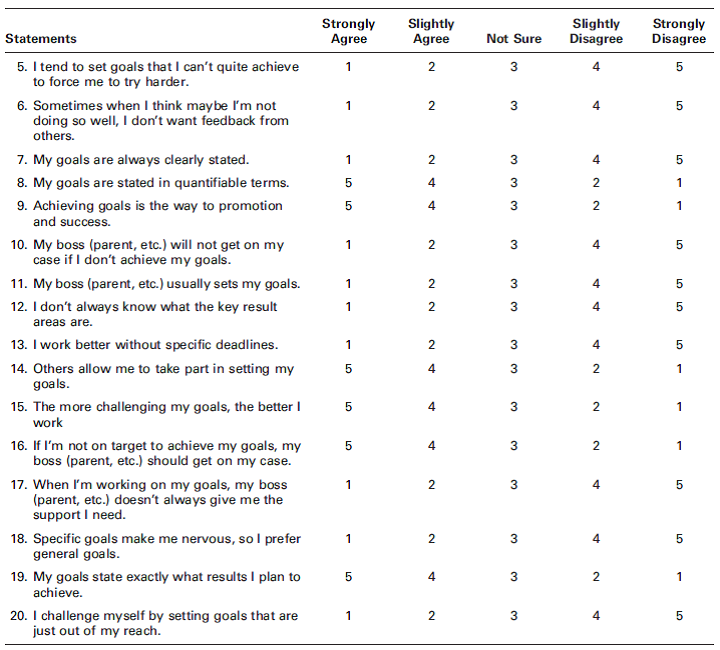

The below mentioned scores would enable the person to evaluate the status of the goal. The higher the scores, the closer the person would have goal-setting behaviors.

The stated statements are scored in the following way:

Statements Score

• Rewards should be allocated based on goal achievements 5

• I set goals for all key result areas 2

• Goals should have clear deadlines 5

• I work hard to give others feedback on how they are doing 4

• I tend to set goals that I can't quite achieve to force me to try

harder. 4

• Sometimes when I think maybe I'm not doing so well

I don't want feedback from others. 4

• My goals are always clearly stated 3

• My goals are stated in quantifiable terms 3

• Achieving goals is the way to promotion and success. 5

• My boss will not get on my case if I don't want them to. 1

• My boss usually sets my goals 5

• I don't always know what are my key result areas 3

• I work better without specific deadlines. 1

• Others allow me to take part in setting my goals. 4

• The more challenging my goals the better I work. 5

• If I'm not on target to achieve my goals my boss should get on

my case.

• When I 'm working on my goals, my boss doesn't always

give me the support I need. 4

• Specific goals make me nervous so I prefer general goals. 1

• My goals state exactly what results I plan to achieve. 2

• I challenge myself by setting goals that are just out of my reach. 5

Hence, the total Score comes out to be 70. This score is pretty closer to 100 and one can conclude that the person has achieved the goal setting behavior to some extent. However, every person has their own set of views and hence would score the statements differently.

2

Exercise Overview

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Finally, ask yourself how confident you would be in basing decisions on the information that you've obtained.

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Finally, ask yourself how confident you would be in basing decisions on the information that you've obtained.

Having shortlisted reliable sources of information internally and through external research, I would be very confident of making a well thought out, comprehensive SWOT analysis of my firm, its products, competitiveness, and recovery and survival strategy.

3

Explain how each of its strategic components- distinctive competence, scope, and resource deployment-plays a role in Toyota's strategy for competing in the U.S. market. Be as specific as you can.

Company T is a Japanese company involved in the manufacturing and sales of automobiles. It entered foreign markets, especially the American market. At that time many companies were already dominant players of the American market. Company T marked their entry by launching Toyopet in the American market.

Distinctive competency is defined as a business organization's unique and specific competency. This set of characteristics sets it apart from other business organizations and marks the organization's superiority. Distinctive competency is an enabling feature of the business's functions through development of unique value propositions.

The distinctive competency of Company T is its unique production system. It is called the Company T Production System or popularly the TPS. It is derived from the concept of Lean Manufacturing. It further works on concepts of Just in Time, Kaizen, Six Sigma etc. These innovative concepts have been rolled together to create the TPS. Consistent and successful application of TPS at Company T has provided it with a distinct advantage in the automobile manufacturer's market. It has been a market leader in USA. The products are reasonably priced, have a charismatic brand name. Their product portfolio is diverse and attractive.

Scope of strategy is defined as the range and diversity of markets a business organization operates and competes in. Company T as a business organization promoted diversification, expanded its scope of business activities. They have interests in electronics, equipment, machinery, logistics solutions, automobiles etc. Their sales network is present globally. They have manufacturing set ups throughout the world including Asia, Europe and even North America. Company T has a broad scope with their operations spanning the entire globe.

Resource Deployment is defined as the set of processes and systems followed by an organization to distribute its resources across its areas of operations, competition and sales. Company T follows the Lean Production System. They believe in accomplishing more results using less resources and time. They use multi skilled workers across several functions. They work through eliminating waste of any kind. Lean thinking is the principle followed across the organization.

Distinctive competency is defined as a business organization's unique and specific competency. This set of characteristics sets it apart from other business organizations and marks the organization's superiority. Distinctive competency is an enabling feature of the business's functions through development of unique value propositions.

The distinctive competency of Company T is its unique production system. It is called the Company T Production System or popularly the TPS. It is derived from the concept of Lean Manufacturing. It further works on concepts of Just in Time, Kaizen, Six Sigma etc. These innovative concepts have been rolled together to create the TPS. Consistent and successful application of TPS at Company T has provided it with a distinct advantage in the automobile manufacturer's market. It has been a market leader in USA. The products are reasonably priced, have a charismatic brand name. Their product portfolio is diverse and attractive.

Scope of strategy is defined as the range and diversity of markets a business organization operates and competes in. Company T as a business organization promoted diversification, expanded its scope of business activities. They have interests in electronics, equipment, machinery, logistics solutions, automobiles etc. Their sales network is present globally. They have manufacturing set ups throughout the world including Asia, Europe and even North America. Company T has a broad scope with their operations spanning the entire globe.

Resource Deployment is defined as the set of processes and systems followed by an organization to distribute its resources across its areas of operations, competition and sales. Company T follows the Lean Production System. They believe in accomplishing more results using less resources and time. They use multi skilled workers across several functions. They work through eliminating waste of any kind. Lean thinking is the principle followed across the organization.

4

Acting on a Strategic Vision

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

If you ran a small video game start-up, what would be your strategy for competing with EA and Activision Blizzard?

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

If you ran a small video game start-up, what would be your strategy for competing with EA and Activision Blizzard?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

Exercise Overview

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

The biggest obstacles to effective planning in the first few minutes of this crisis were the rapid and unexpected changes occurring in a dynamic and complex environment. List elements of the situation that contributed to dynamism (elements that were rapidly changing). List elements that contributed to complexity. What kinds of actions did NASA's planning staff take to overcome the obstacles presented by the dynamic and complex environment? Suggest any other useful actions the staff could have taken.

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

The biggest obstacles to effective planning in the first few minutes of this crisis were the rapid and unexpected changes occurring in a dynamic and complex environment. List elements of the situation that contributed to dynamism (elements that were rapidly changing). List elements that contributed to complexity. What kinds of actions did NASA's planning staff take to overcome the obstacles presented by the dynamic and complex environment? Suggest any other useful actions the staff could have taken.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

What kind of plan-tactical or operational- should be developed first? Why? Does the order really matter? Why or why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Exercise Overview

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Then ask yourself: For what types of information are data readily available on the Internet? What categories of data are difficult or impossible to find on the Internet? (Note: When using the Internet, be sure to provide specific websites or URLs.)

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Then ask yourself: For what types of information are data readily available on the Internet? What categories of data are difficult or impossible to find on the Internet? (Note: When using the Internet, be sure to provide specific websites or URLs.)

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

What is tactical planning? What is operational planning? What are the similarities and differences between them?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Acting on a Strategic Vision

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

How might Porter's generic strategies theory help to explain why Electronic Arts lost its leadership in the video game market to Activision Blizzard?

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

How might Porter's generic strategies theory help to explain why Electronic Arts lost its leadership in the video game market to Activision Blizzard?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

A statement issued by the Union of Concerned Scientists in 2007 called Toyota "the poster child for an auto industry with an identity crisis…. At the same time that Toyota is producing ads with hybrids driving through green fields, it's making less fuel-efficient vehicles [especially trucks] and its lobbyists are pushing for a watered-down fuel economy law." Does this seem to be a reasonable (and fair) assessment of the automaker's strategy as it's described in the case? Whether you say yes or no, explain youranswer.*

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

Which strategy-business or corporate level- should a firm develop first? Describe the relationship between a firm's business- and corporate-level strategies.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

Acting on a Strategic Vision

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

If you're a video game player, what aspects of Activision's strategy have led to your playing more (or fewer) of its games? If you're not a video game player, what aspects of Activision Blizzard's strategy might induce you to try a few of its games?

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.

The strategy paid off big time. For calendar year 2007, the company, now known as Activision Blizzard, estimated compiled revenues of $3.8 billion-just enough to squeeze past EA's $3.7 billion and sneak into the top spot as the bestselling video game publisher in the world not affiliated with a maker of game consoles (such as Nintendo and Microsoft). Revenues for calendar year 2010 were $4.4 billion, up more than 20 percent over 2009, making Activision Blizzard the number one video game publisher in North America and Europe. Today, its market capitalization of $13.3 billion is nearly twice that of EA. Kotick attributes the firm's success to a "focus on a select number of proven franchises and genres where we have proven development expertise…. We look for ways to broaden the footprints of our franchises, and where appropriate, we develop innovative business models like subscription-based online gaming."

If you're a video game player, what aspects of Activision's strategy have led to your playing more (or fewer) of its games? If you're not a video game player, what aspects of Activision Blizzard's strategy might induce you to try a few of its games?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Identify and describe Porter's generic strategies.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

Cite examples of operational plans that you use or encounter (now or in the past) at work, at school, or in your personal life.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

The SWOT Analysis

Purpose: The SWOT analysis provides the manager with a cognitive model of the organization and its environmental forces. By developing the ability to conduct such an analysis, the manager builds both process knowledge and a conceptual skill. This skill builder focuses on the administrative management model. It will help you develop the coordinator role of the administrative management model. One of the skills of the coordinator is the ability to plan.

Introduction: This exercise helps you understand the complex interrelationships between environmental opportunities and threats and organizational strengths and weaknesses. Strategy formulation is facilitated by a SWOT analysis. First, the organization should study its internal operations to identify its strengths and weaknesses. Next, the organization should scan the environment to identify existing and future opportunities and threats. Then, the organization should identify the relationships that exist among these strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Finally, major business strategies usually result from matching an organization's strengths with appropriate opportunities or from matching the threats it faces with weaknesses that have been identified.

Instructions: First, read the short narrative of the Trek Bicycle Corporation's external and internal environments, found next in this chapter.

Second, divide into small group, and conduct a SWOT analysis for Trek based on the short narrative. You may also use your general knowledge and any information you have about Trek or the bicycle manufacturing industry. Then prepare a group response to the discussion questions.

Third, as a class, discuss both the SWOT analysis and the groups' responses to the discussion questions.

Why do most firms not develop major strategies for matches between threats and strengths?

Purpose: The SWOT analysis provides the manager with a cognitive model of the organization and its environmental forces. By developing the ability to conduct such an analysis, the manager builds both process knowledge and a conceptual skill. This skill builder focuses on the administrative management model. It will help you develop the coordinator role of the administrative management model. One of the skills of the coordinator is the ability to plan.

Introduction: This exercise helps you understand the complex interrelationships between environmental opportunities and threats and organizational strengths and weaknesses. Strategy formulation is facilitated by a SWOT analysis. First, the organization should study its internal operations to identify its strengths and weaknesses. Next, the organization should scan the environment to identify existing and future opportunities and threats. Then, the organization should identify the relationships that exist among these strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Finally, major business strategies usually result from matching an organization's strengths with appropriate opportunities or from matching the threats it faces with weaknesses that have been identified.

Instructions: First, read the short narrative of the Trek Bicycle Corporation's external and internal environments, found next in this chapter.

Second, divide into small group, and conduct a SWOT analysis for Trek based on the short narrative. You may also use your general knowledge and any information you have about Trek or the bicycle manufacturing industry. Then prepare a group response to the discussion questions.

Third, as a class, discuss both the SWOT analysis and the groups' responses to the discussion questions.

Why do most firms not develop major strategies for matches between threats and strengths?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

What is contingency planning? How is it similar to and different from crisis management?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

In what ways is Toyota's strategy designed to respond to both organizational opportunities and organizational threats in the U.S. market?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

Exercise Overview

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

NASA managers and astronauts did not use a formal planning process in their approach to this situation. Why not? Is there any part of the formal planning process that could have been helpful? What does this example suggest to you about the advantages and limitations of the formal planning process?

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

NASA managers and astronauts did not use a formal planning process in their approach to this situation. Why not? Is there any part of the formal planning process that could have been helpful? What does this example suggest to you about the advantages and limitations of the formal planning process?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

Exercise Overview

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

Watch and listen to the short clip from Apollo 13. (This movie was made by Universal Studios in 1995 and was directed by Ron Howard. The script was based on a memoir by astronaut and Apollo 13 mission captain Jim Lovell.) Describe the various types of planning and decision making activities taking place at NASA during the unfolding of the disaster.

Interpersonal skills refer to the manager's ability to communicate with, understand, and motivate individuals and groups. Communication skills are used both to convey information to others effectively and to receive ideas and information effectively from others. Communicating and interacting effectively with many different types of individuals are essential planning skills. This exercise allows you to think through communication and interaction issues as they relate to an actual planning situation.

Exercise Background

Larger and more complex organizations require greater planning complexity to achieve their goals. NASA is responsible for the very complex task of managing U.S. space exploration and therefore has very complex planning needs.

In April 1970, NASA launched the Apollo 13 manned space mission, which was charged with exploration of the lunar surface. On its way to the moon, the ship developed a malfunction that could have resulted in the death of all the crew members. The crew members worked with scientists in Houston to develop a solution to the problem. The capsule was successful in returning to Earth, and no lives were lost.

Exercise Task

Watch and listen to the short clip from Apollo 13. (This movie was made by Universal Studios in 1995 and was directed by Ron Howard. The script was based on a memoir by astronaut and Apollo 13 mission captain Jim Lovell.) Describe the various types of planning and decision making activities taking place at NASA during the unfolding of the disaster.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

20

Exercise Overview

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Next, rate each source that you consult in terms of probable reliability.

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

Next, rate each source that you consult in terms of probable reliability.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

21

Exercise Overview

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

List the sources that you'll use to gather information about the firm's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Decision-making skills refer to the ability to recognize and define problems and opportunities correctly and then to select an appropriate course of action for solving problems or capitalizing on opportunities. As we noted in this chapter, many organizations use SWOT analysis as part of the strategy formulation process. This exercise will help you better understand both how managers obtain the information they need to perform such an analysis and how they use it as a framework for making decisions.

Exercise Background

The idea behind SWOT is that a good strategy exploits an organization's opportunities and strengths while neutralizing threats and avoiding or correcting weaknesses. You've just been hired to run a medium-sized company that manufactures electric motors, circuit breakers, and similar electronic components for industrial use. In recent years, the firm's financial performance has gradually eroded, and your job is to turn things around. At one time, the firm was successful in part because it was able to charge premium prices for top-quality products. In recent years, however, management has tried cutting costs as a means of bringing prices in line with those of new competitors in the market. Unfortunately, the strategy hasn't worked very well, with the effect of cost cutting being primarily a fall-off in product quality. Convinced that a new strategy is called for, you've decided to begin with a SWOT analysis.

Exercise Task

Reviewing the situation, you take the following steps:

List the sources that you'll use to gather information about the firm's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

22

Acting on a Strategic Vision

Established as Amazin' Software in 1982 by an ex-Apple marketing executive named Trip Hawkins, Electronic Arts (EA) was a pioneer in the home computer game industry. From the outset, EA published games created by outside developers-a strategy that offered higher profit margins and forced the new company to stay in close contact with its market. By 1984, having built the largest sales force in the industry, EA had generated revenue of $18 million. Crediting its developers as "software artists," EA regularly gave game creators photo credits on packaging and advertising spreads and, what's more important, developed a generous profit-sharing policy that helped it to attract some of the industry's best development talent.

By 1986, the company had become the country's largest supplier of entertainment software. It went public in 1989, and net revenue took off in the early 1990s,climbing from $113 million in 1991 to $298 million in 1993. In the next 13 years, the company continued to grow by developing two key strategies:

• Acquiring independent game makers (at the rate of 1.2 studios per year between 1995 and 2006)

• Rolling out products in series, such as John Madden Football, Harry Potter, and Need for Speed

Activision's path to success in the industry wasn't quite as smooth as EA's. Activision was founded in 1979 as a haven for game developers unhappy with prevailing industry policy. At the time, systems providers like Atari hired developers to create games only for their own systems; in-house developers were paid straight salaries and denied credit for individual contributions, and there was no channel at all for would-be independents. Positioning itself as the industry's first third-party developer, Activision began promoting creators as well as games. The company went public in 1983 and successfully rode the crest of a booming market until the mid-1980s. Between 1986 and 1990, however, Activision's growth strategies-acquisitions and commitment to a broader product line-fizzled, and it had become, as Forbes magazine put it, "a company with a sorry balance sheet but a storied history."

Enter Robert Kotick, a serial entrepreneur with no particular passion for video games, who bought one fourth of the firm in December 1990 and became CEO two months later. Kotick looked immediately to Electronic Arts for a survey of best practices in the industry. What he discovered was a company whose culture was disrupted by internal conflict-namely, between managers motivated by productivity and profit and developers driven by independence and imagination. It seems that EA's strategy for acquiring and managing a burgeoning portfolio of studios had slipped into a counterproductive pattern: Identify an extremely popular game, buy the developer, delegate the original creative team to churn out sequels until either the team burned out or the franchise fizzled, and then close down or absorb what was left.

On the other hand, EA still sold a lot of video games, and to Kotick, the basic tension in EA culture wasn't entirely surprising: Clearly the business of making and marketing video games succeeded when the creative side of the enterprise was supported by financing and distribution muscle, but it was equally true that a steady stream of successful games came from the company's creative people. The key to getting Activision back in the game, Kotick decided, was managing this complex of essential resources better than his competition did.

So the next year Kotick moved the company to Los Angeles and began to recruit the people who could furnish the resources that he needed most-creative expertise and a connection with the passion that its customers brought to the video-game industry. Activision, he promised prospective developers, would not manage its human resources the way that EA did: EA, he argued, "has commoditized development. We won't absorb you into a big Death Star culture."

Between 1997 and 2003, Kotick proceeded to buy no fewer than nine studios, but his concept of a videogame studio system was quite different from that of EA, which was determined to make production more efficient by centralizing groups of designers and programmers into regional offices. Kotick allows his studios to keep their own names, often lets them stay where they are, and further encourages autonomy by providing seed money for Activision alumni who want to launch out on their own. Each studio draws up its own financial statements and draws on its own bonus pool, and the paychecks of studio heads reflect companywide profits and losses.