Deck 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/98

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics

1

Many firms reduce their outstanding debt relative to equity and such changes in the capital structure distort valuation estimates based on traditional DCF methods.

True

2

The adjusted present value method values firm without debt and then subtracts the value of future tax savings resulting from the tax-deductibility of interest.

False

3

Because the firm's cost of equity changes over time,the firm's cumulative cost of equity is used to discount projected cash flows.This reflects the fact that each period's cash flows generate a different rate of return.

True

4

Some analysts suggest that the problem of a variable discount rate can be avoided by separating the value of a firm's operations into two components: the firm's value as if it were debt free and the value of interest tax savings.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

For simplicity,the market value of common equity can be assumed to grow in line with the projected growth in a firm's account receivables.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

The deal makes sense to lenders and noncommon equity investors if the present value of free cash flow to equity investors exceeds the total cost of the deal.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

An LBO transaction makes sense from the viewpoint of all investors if the present value (of the cash flows to the firm or enterprise value,discounted at the weighted-average cost of capital,equals or exceeds the total investment consisting of debt,common equity,and preferred equity required to buy the outstanding shares of the target company.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Using the adjusted present value method to value a LBA assumes the total value of the firm is the present value of the firm's free cash flows to lenders plus the present value of future tax savings discounted at the firm's unlevered cost of equity.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

The extremely high leverage associated with leveraged buyouts significantly increases the riskiness of the cash flows available to equity investors as a result of the increase in fixed interest and principal repayments that must be made to lenders.Consequently,the cost of equity should be adjusted for the increased leverage of the firm.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Projecting future annual debt-to-equity ratios depends on knowing the firm's debt repayment schedules and projecting growth in the market value of shareholders' equity.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

An LBO can be valued from the perspective of common equity investors only or all those who supply funds,including common and preferred investors and lenders.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

As the LBO's extremely high debt level is reduced,the cost of equity needs to be adjusted to reflect the decline in risk,as measured by the firm's unlevered beta.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

If the debt-to-equity ratio is expected to fluctuate substantially during the forecast period,applying conventional capital budgeting techniques that discount future cash flows with a constant weighted average cost of capital (CC)is appropriate.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

It is impossible for a leveraged buyout to make sense to common equity investors but not to other investors,such as pre-LBO debt holders and preferred stockholders.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

Once the LBO has been consummated,the firm's perceived ability to meet its obligations to current debt and preferred stockholders often deteriorates because the firm takes on a substantial amount of new debt.The firm's pre-LBO debt and preferred stock may be revalued in the market by investors to reflect this higher perceived risk,resulting in a significant reduction in the market value of both debt and preferred equity owned by pre-LBO investors.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

Using the cost of capital method to value LBOs requires adjusting the firms unlevered beta in each period using the firm's projected debt-to-equity ratio for that period.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

An LBO deal makes sense to common equity investors if the present value of free cash flow to equity exceeds the value of the equity investment in the deal.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

Since an LBO's debt is to be paid off over time,the cost of equity decreases over time,assuming other factors remain unchanged.Therefore,in valuing a leveraged buyout,the analyst must project free cash flows,adjusting the discount rate to reflect changes in the capital structure.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

Conventional capital budgeting procedures are of little use in valuing an LBO.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

20

The cost of capital method attempts to adjust future cash flows for changes in the cost of capital as the firm reduces its outstanding debt.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

21

Without adjusting for the cost of financial distress,the adjusted present value method implies that the value of the firm could be increased by continuously taking on more debt.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

22

Increased borrowing by a firm will,other things equal,increase its tax liability.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

23

The total value of the firm according to the adjusted present value method is the present value of the firm's free cash flows to equity investors plus the present value of future tax savings discounted at the firm's unlevered cost of equity.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

24

Financial distress does not have a material indirect cost to firms able to avoid bankruptcy or liquidation.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

25

The adjusted present value method implies that the firm should optimally use 100% debt financing to take maximum advantage of the tax shield created by the tax deductibility of interest.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

26

Although the proposition that the value of the firm should be independent of the way in which it is financed may make sense for a firm whose debt-to-capital ratio is relatively stable and similar to the industry's,it is highly problematic when it is applied to highly leveraged transactions.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

27

The unlevered cost of equity is often viewed as the appropriate discount rate rather than the cost of debt or a risk-free rate because tax savings are subject to risk,since the firm may default on its debt or be unable to utilize the tax savings due to continuing operating losses.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

28

To determine the total value of the firm using the adjusted present value method,add the present value of the firm's cash flows to equity,interest tax savings,and terminal value discounted at the firm's unlevered cost of equity and subtract the present value of the expected cost of financial distress.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

29

The expected cost of and probability of occurring of financial distress are easily forecasted.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

30

The present value of tax savings is irrelevant to the adjusted present value method.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

31

In the presence of taxes,firms are often less leveraged than they should be,given the potentially large tax benefits associated with debt.Firms can increase market value by increasing leverage to the point at which the additional contribution of the tax shield to the firm's market value begins to decline.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

32

In using the adjusted present value method to value highly leveraged transactions,the analyst need not be concerned about the costs of financial distress.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

33

The justification for the adjusted present value (APV)method reflects the theoretical notion that firm value should not be affected by the way in which it is financed.However,recent studies empirical suggest that for LBOs,the availability and cost of financing does indeed impact financing and investment decisions.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

34

The direct cost of financial distress includes the costs associated with reorganization in bankruptcy and ultimately liquidation.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

35

In discount projected tax savings in the adjusted present value method,the firm's unlevered cost of equity should be used,since it reflects a higher level of risk than either the WACC or after-tax cost of debt.Tax savings are subject to risk comparable to the firm's cash flows in that a highly leveraged firm may default and the tax savings go unused.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

36

The justification for the adjusted present value method reflects the theoretical notion that firm value should is affected by the way in which it is financed.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

37

In the adjusted present value method,the levered cost of equity is used for discounting cash flows during the period in which the capital structure is changing and the weighted-average cost of capital for discounting during the terminal period.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

38

The tax benefits of higher leverage may be partially or entirely offset by the higher probability of default associated with an increase in leverage.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

39

Many analysts use the cost of capital method because of its relative simplicity.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

40

In applying the adjusted present value method,the present value of a highly leveraged transaction should reflect the present value of the firm without leverage plus the present value of tax savings plus the present value of expected financial distress.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

41

Which of the following is true of the cost of capital method of valuation?

A) It is generally more tedious to calculate than alternative methodologies

B) It requires the separate estimation of the present value of future tax savings

C) It adds the present value of the firm without debt to the present value of tax savings

D) It does not adjust the discount rate as debt is repaid

E) All of the above

A) It is generally more tedious to calculate than alternative methodologies

B) It requires the separate estimation of the present value of future tax savings

C) It adds the present value of the firm without debt to the present value of tax savings

D) It does not adjust the discount rate as debt is repaid

E) All of the above

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

42

An LBO model is used to determine what a firm is worth in a highly leveraged transaction and is applied when there is the potential for a financial buyer or sponsor to acquire the business.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

43

While the DCF approach often is more theoretically sound than the IRR approach (which can have multiple solutions),IRR is more widely used in LBO analyses since investors often find it more intuitively appealing,that is,the higher an investment's IRR,the better the investment's return relative to its cost The IRR is the discount rate that equates the projected cash flows and terminal value with the initial equity investment.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

44

Using the cost of capital method to value an LBO involves all of the following steps except for which of the following?

A) Adjusting the discount rate to reflect changing risk.

B) Adding the present value of future tax savings to the present value of annual free cash flows to equity.

C) Calculating a terminal value.

D) Projecting annual debt-to-equity ratios.

E) Projecting annual cash flows.

A) Adjusting the discount rate to reflect changing risk.

B) Adding the present value of future tax savings to the present value of annual free cash flows to equity.

C) Calculating a terminal value.

D) Projecting annual debt-to-equity ratios.

E) Projecting annual cash flows.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

45

The primary advantage of the cost of capital method is its relative computational simplicity.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

46

The DCF analysis solves for the present value of the firm,while the LBO analysis solves for the discount rate or internal rate of return.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

47

LBO analyses are similar to DCF valuations in that they require projected cash flows,present values,and discount rates; however,LBO models do not require the estimation of terminal values.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

48

The adjusted present value approach takes into account the effects of leverage on risk as debt is repaid.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

49

Which of the following are steps often found in developing a LBO model?

A) Cash flow projections

B) Determining a firm's borrowing capacity

C) Determining a financial sponsor's equity contribution

D) A, B, and C

E) A and C only

A) Cash flow projections

B) Determining a firm's borrowing capacity

C) Determining a financial sponsor's equity contribution

D) A, B, and C

E) A and C only

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

50

An LBO model helps define the amount of debt a firm can support given its assets and cash flows.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

51

An LBO can be valued from the perspective of which of the following?

A) Equity investors

B) Lenders

C) All those supplying funds to finance the transaction

D) A and B only

E) A, B, and C

A) Equity investors

B) Lenders

C) All those supplying funds to finance the transaction

D) A and B only

E) A, B, and C

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

52

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

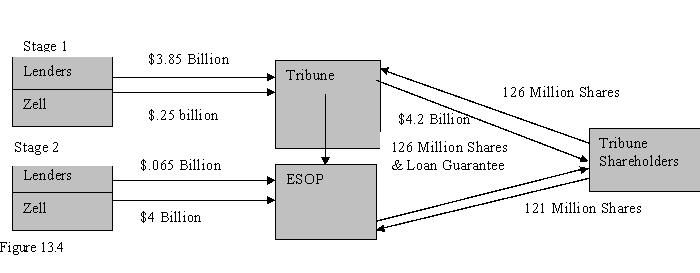

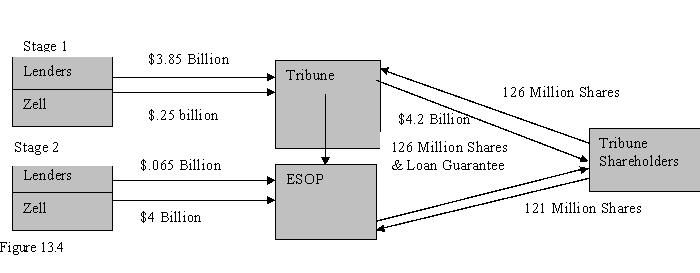

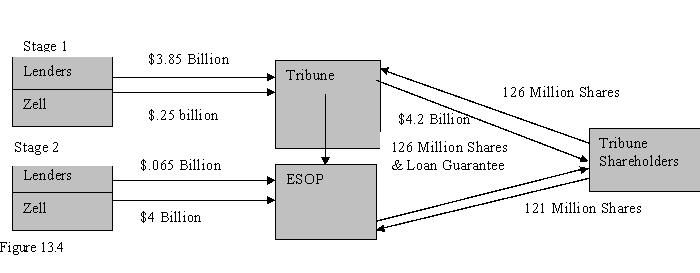

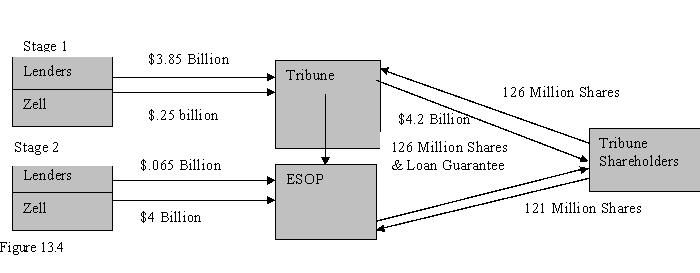

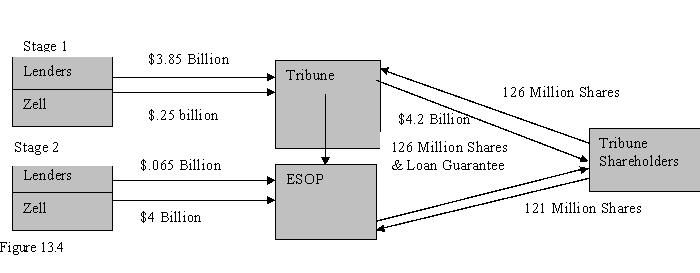

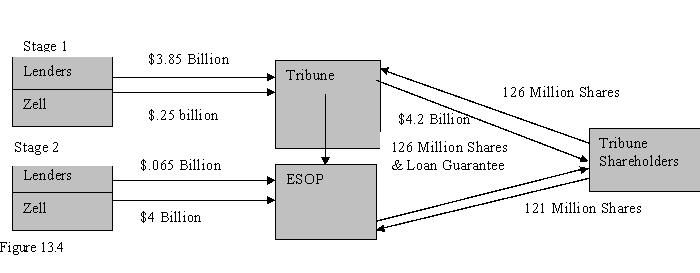

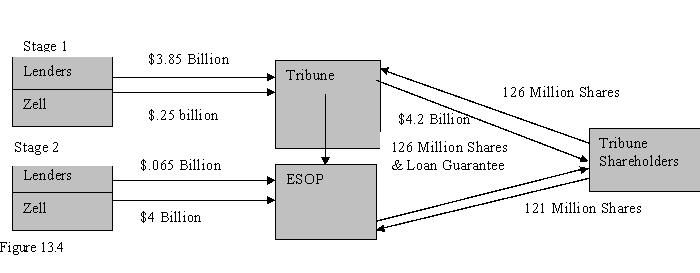

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

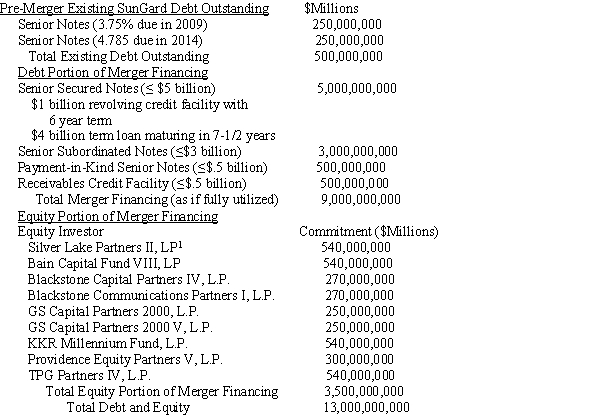

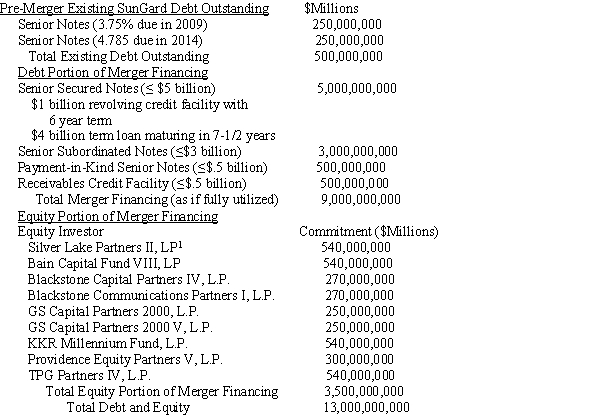

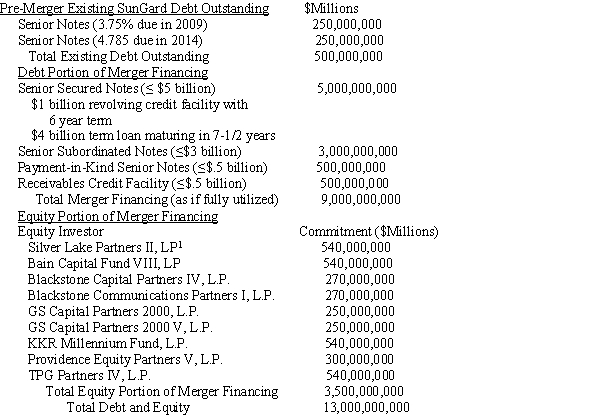

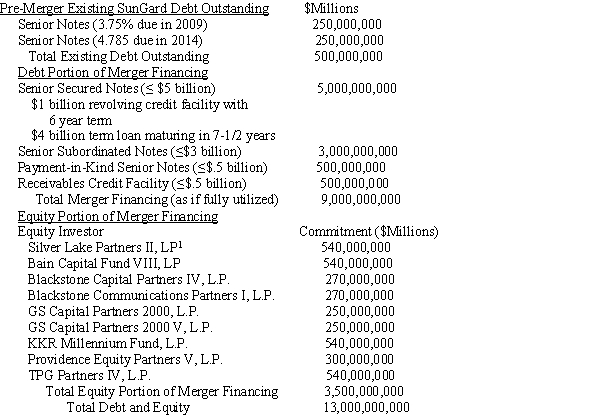

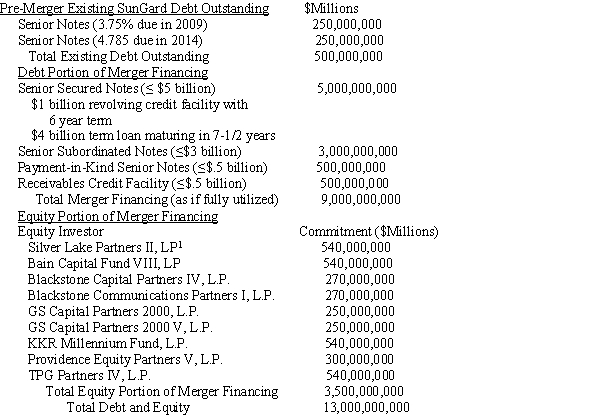

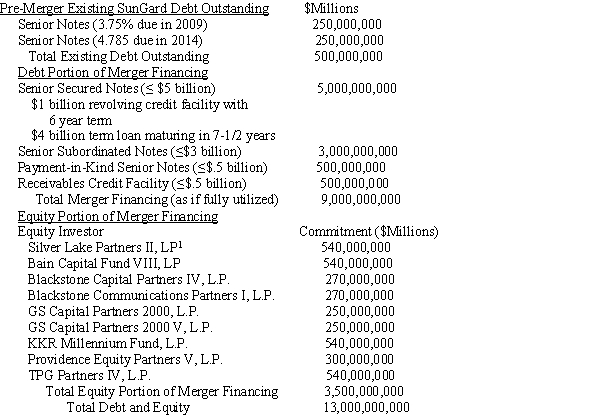

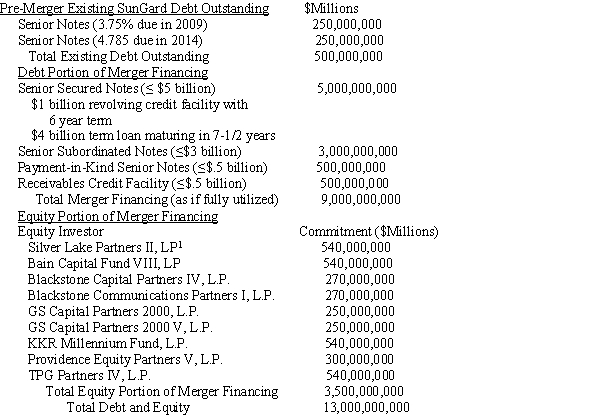

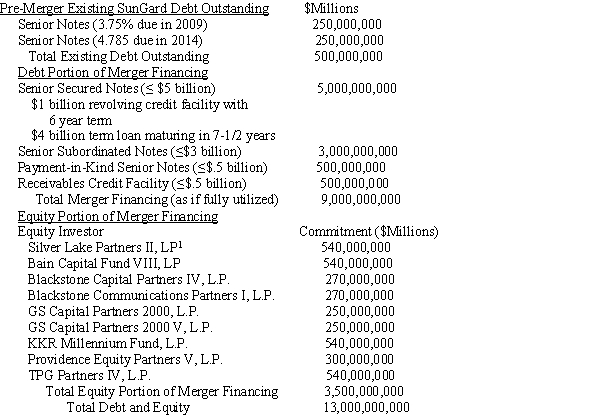

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4). Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

Describe the firm's strategy to finance the transaction?

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

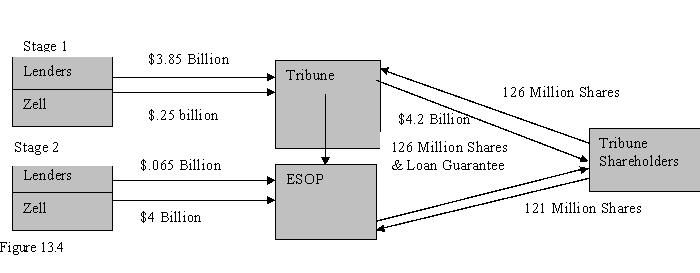

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).

Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

Describe the firm's strategy to finance the transaction?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

53

Which of the following is not true about the cost of capital method of valuation?

A) It does not adjust the discount rate for risk as debt is repaid.

B) It requires the projection of future cash flows

C) It requires the projection of future debt-to-equity ratios.

D) It requires the calculation of a terminal value

E) None of the above

A) It does not adjust the discount rate for risk as debt is repaid.

B) It requires the projection of future cash flows

C) It requires the projection of future debt-to-equity ratios.

D) It requires the calculation of a terminal value

E) None of the above

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

54

Which of the following is true of the adjusted present value method of valuation?

A) Calculates the present value of tax benefits separately

B) Calculates the present value of the firm's cash flow without debt

C) Adds A and B together

D) A, B, and C

E) A and B only

A) Calculates the present value of tax benefits separately

B) Calculates the present value of the firm's cash flow without debt

C) Adds A and B together

D) A, B, and C

E) A and B only

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

55

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

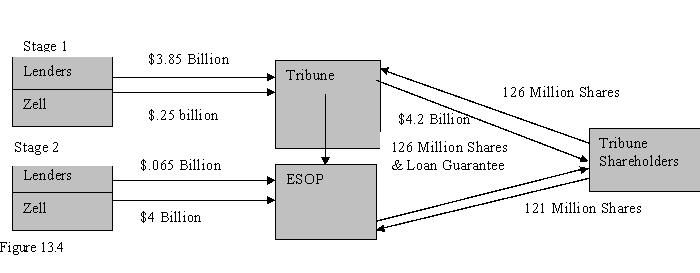

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4). Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

What is the acquisition vehicle,post-closing organization,form of payment,form of acquisition,and tax

strategy described in this case study?

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).

Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

What is the acquisition vehicle,post-closing organization,form of payment,form of acquisition,and tax

strategy described in this case study?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

56

The riskiness of highly leveraged transactions declines overtime due to which of the following factors?

A) Debt reduction assuming nothing else changes

B) Increasing discount rates

C) A rising unlevered beta

D) An unchanging cost of equity

E) An unchanging weighted average cost of capital

A) Debt reduction assuming nothing else changes

B) Increasing discount rates

C) A rising unlevered beta

D) An unchanging cost of equity

E) An unchanging weighted average cost of capital

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

57

Using the cost of capital method to value an LBO involves which of the following steps?

A) Projection of annual cash flows

B) Projection of annual debt-to-equity ratios

C) Calculation of a terminal value

D) Adjusting the discount rate to reflect changing risk.

E) All of the above

A) Projection of annual cash flows

B) Projection of annual debt-to-equity ratios

C) Calculation of a terminal value

D) Adjusting the discount rate to reflect changing risk.

E) All of the above

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

58

Which of the following is not true about LBO models?

A) They rarely use IRR calculations

B) Borrowing capacity is relatively unimportant

C) The financial sponsor's equity contribution is determined before the target firm's borrowing capacity

D) A, B, and C

E) A and B only

A) They rarely use IRR calculations

B) Borrowing capacity is relatively unimportant

C) The financial sponsor's equity contribution is determined before the target firm's borrowing capacity

D) A, B, and C

E) A and B only

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

59

Which of the following are often viewed as disadvantages of the adjusted present value method?

A) Ignores the effects of leverage on the discount rate as debt is repaid

B) Requires estimation of the cost and probability of financial distress

C) It is unclear how to define the proper discount rate

D) A and B only

E) A, B, and C

A) Ignores the effects of leverage on the discount rate as debt is repaid

B) Requires estimation of the cost and probability of financial distress

C) It is unclear how to define the proper discount rate

D) A and B only

E) A, B, and C

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

60

Financial buyers often will attempt to determine the highest amount of debt possible (i.e.,the borrowing capacity of the target firm)to maximize their equity contribution in order to maximize the IRR.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

61

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

RJR NABISCO GOES PRIVATE-

KEY SHAREHOLDER AND PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES

Background

The largest LBO in history is as well known for its theatrics as it is for its substantial improvement in shareholder value. In October 1988, H. Ross Johnson, then CEO of RJR Nabisco, proposed an MBO of the firm at $75 per share. His failure to inform the RJR board before publicly announcing his plans alienated many of the directors. Analysts outside the company placed the breakup value of RJR Nabisco at more than $100 per share-almost twice its then current share price. Johnson's bid immediately was countered by a bid by the well-known LBO firm, Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts (KKR), to buy the firm for $90 per share (Wasserstein, 1998). The firm's board immediately was faced with the dilemma of whether to accept the KKR offer or to consider some other form of restructuring of the company. The board appointed a committee of outside directors to assess the bid to minimize the appearance of a potential conflict of interest in having current board members, who were also part of the buyout proposal from management, vote on which bid to select.

The bidding war soon escalated with additional bids coming from Forstmann Little and First Boston, although the latter's bid never really was taken very seriously. Forstmann Little later dropped out of the bidding as the purchase price rose. Although the firm's investment bankers valued both the bids by Johnson and KKR at about the same level, the board ultimately accepted the KKR bid. The winning bid was set at almost $25 billion-the largest transaction on record at that time and the largest LBO in history. Banks provided about three-fourths of the $20 billion that was borrowed to complete the transaction. The remaining debt was supplied by junk bond financing. The RJR shareholders were the real winners, because the final purchase price constituted a more than 100% return from the $56 per share price that existed just before the initial bid by RJR management.

Aggressive pricing actions by such competitors as Phillip Morris threatened to erode RJR Nabisco's ability to service its debt. Complex securities such as "increasing rate notes," whose coupon rates had to be periodically reset to ensure that these notes would trade at face value, ultimately forced the credit rating agencies to downgrade the RJR Nabisco debt. As market interest rates climbed, RJR Nabisco did not appear to have sufficient cash to accommodate the additional interest expense on the increasing return notes. To avoid default, KKR recapitalized the company by investing additional equity capital and divesting more than $5 billion worth of businesses in 1990 to help reduce its crushing debt load. In 1991, RJR went public by issuing more than $1 billion in new common stock, which placed about one-fourth of the firm's common stock in public hands.

When KKR eventually fully liquidated its position in RJR Nabisco in 1995, it did so for a far smaller profit than expected. KKR earned a profit of about $60 million on an equity investment of $3.1 billion. KKR had not done well for the outside investors who had financed more than 90% of the total equity investment in KKR. However, KKR fared much better than investors had in its LBO funds by earning more than $500 million in transaction fees, advisor fees, management fees, and directors' fees. The publicity surrounding the transaction did not cease with the closing of the transaction. Dissident bondholders filed suits alleging that the payment of such a large premium for the company represented a "confiscation" of bondholder wealth by shareholders.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

In any MBO, management is confronted by a potential conflict of interest. Their fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders is to take actions to maximize shareholder value; yet in the RJR Nabisco case, the management bid appeared to be well below what was in the best interests of shareholders. Several proposals have been made to minimize the potential for conflict of interest in the case of an MBO, including that directors, who are part of an MBO effort, not be allowed to participate in voting on bids, that fairness opinions be solicited from independent financial advisors, and that a firm receiving an MBO proposal be required to hold an auction for the firm.

The most contentious discussion immediately following the closing of the RJR Nabisco buyout centered on the alleged transfer of wealth from bond and preferred stockholders to common stockholders when a premium was paid for the shares held by RJR Nabisco common stockholders. It often is argued that at least some part of the premium is offset by a reduction in the value of the firm's outstanding bonds and preferred stock because of the substantial increase in leverage that takes place in LBOs.

Winners and Losers

RJR Nabisco shareholders before the buyout clearly benefited greatly from efforts to take the company private. However, in addition to the potential transfer of wealth from bondholders to stockholders, some critics of LBOs argue that a wealth transfer also takes place in LBO transactions when LBO management is able to negotiate wage and benefit concessions from current employee unions. LBOs are under greater pressure to seek such concessions than other types of buyouts because they need to meet huge debt service requirements.

:

In your opinion,was the buyout proposal presented by Ross Johnson's management group in the best interests of the shareholders? Why? / Why not?

RJR NABISCO GOES PRIVATE-

KEY SHAREHOLDER AND PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES

Background

The largest LBO in history is as well known for its theatrics as it is for its substantial improvement in shareholder value. In October 1988, H. Ross Johnson, then CEO of RJR Nabisco, proposed an MBO of the firm at $75 per share. His failure to inform the RJR board before publicly announcing his plans alienated many of the directors. Analysts outside the company placed the breakup value of RJR Nabisco at more than $100 per share-almost twice its then current share price. Johnson's bid immediately was countered by a bid by the well-known LBO firm, Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts (KKR), to buy the firm for $90 per share (Wasserstein, 1998). The firm's board immediately was faced with the dilemma of whether to accept the KKR offer or to consider some other form of restructuring of the company. The board appointed a committee of outside directors to assess the bid to minimize the appearance of a potential conflict of interest in having current board members, who were also part of the buyout proposal from management, vote on which bid to select.

The bidding war soon escalated with additional bids coming from Forstmann Little and First Boston, although the latter's bid never really was taken very seriously. Forstmann Little later dropped out of the bidding as the purchase price rose. Although the firm's investment bankers valued both the bids by Johnson and KKR at about the same level, the board ultimately accepted the KKR bid. The winning bid was set at almost $25 billion-the largest transaction on record at that time and the largest LBO in history. Banks provided about three-fourths of the $20 billion that was borrowed to complete the transaction. The remaining debt was supplied by junk bond financing. The RJR shareholders were the real winners, because the final purchase price constituted a more than 100% return from the $56 per share price that existed just before the initial bid by RJR management.

Aggressive pricing actions by such competitors as Phillip Morris threatened to erode RJR Nabisco's ability to service its debt. Complex securities such as "increasing rate notes," whose coupon rates had to be periodically reset to ensure that these notes would trade at face value, ultimately forced the credit rating agencies to downgrade the RJR Nabisco debt. As market interest rates climbed, RJR Nabisco did not appear to have sufficient cash to accommodate the additional interest expense on the increasing return notes. To avoid default, KKR recapitalized the company by investing additional equity capital and divesting more than $5 billion worth of businesses in 1990 to help reduce its crushing debt load. In 1991, RJR went public by issuing more than $1 billion in new common stock, which placed about one-fourth of the firm's common stock in public hands.

When KKR eventually fully liquidated its position in RJR Nabisco in 1995, it did so for a far smaller profit than expected. KKR earned a profit of about $60 million on an equity investment of $3.1 billion. KKR had not done well for the outside investors who had financed more than 90% of the total equity investment in KKR. However, KKR fared much better than investors had in its LBO funds by earning more than $500 million in transaction fees, advisor fees, management fees, and directors' fees. The publicity surrounding the transaction did not cease with the closing of the transaction. Dissident bondholders filed suits alleging that the payment of such a large premium for the company represented a "confiscation" of bondholder wealth by shareholders.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

In any MBO, management is confronted by a potential conflict of interest. Their fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders is to take actions to maximize shareholder value; yet in the RJR Nabisco case, the management bid appeared to be well below what was in the best interests of shareholders. Several proposals have been made to minimize the potential for conflict of interest in the case of an MBO, including that directors, who are part of an MBO effort, not be allowed to participate in voting on bids, that fairness opinions be solicited from independent financial advisors, and that a firm receiving an MBO proposal be required to hold an auction for the firm.

The most contentious discussion immediately following the closing of the RJR Nabisco buyout centered on the alleged transfer of wealth from bond and preferred stockholders to common stockholders when a premium was paid for the shares held by RJR Nabisco common stockholders. It often is argued that at least some part of the premium is offset by a reduction in the value of the firm's outstanding bonds and preferred stock because of the substantial increase in leverage that takes place in LBOs.

Winners and Losers

RJR Nabisco shareholders before the buyout clearly benefited greatly from efforts to take the company private. However, in addition to the potential transfer of wealth from bondholders to stockholders, some critics of LBOs argue that a wealth transfer also takes place in LBO transactions when LBO management is able to negotiate wage and benefit concessions from current employee unions. LBOs are under greater pressure to seek such concessions than other types of buyouts because they need to meet huge debt service requirements.

:

In your opinion,was the buyout proposal presented by Ross Johnson's management group in the best interests of the shareholders? Why? / Why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

62

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

HCA's LBO Represents a High-Risk Bet on Growth

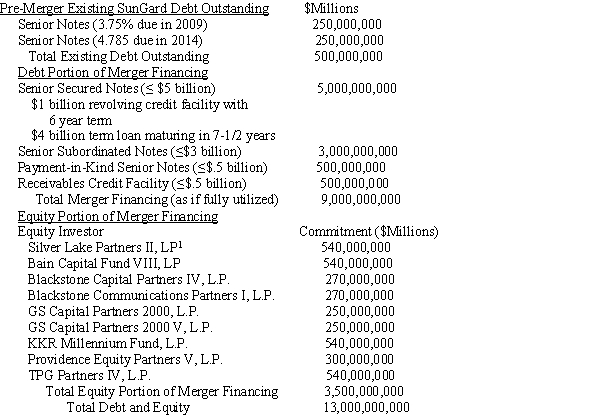

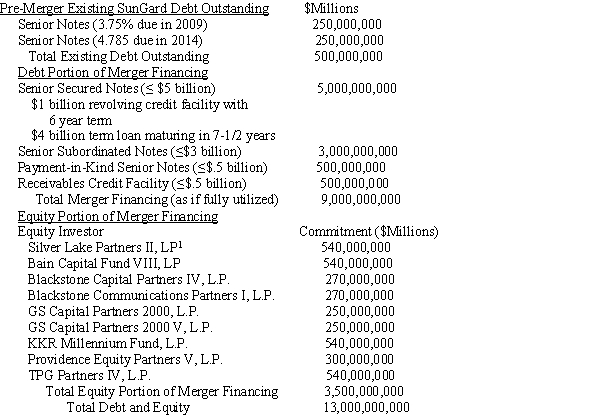

While most LBOs are predicated on improving operating performance through a combination of aggressive cost cutting and revenue growth, HCA laid out an unconventional approach in its effort to take the firm private. On July 24, 2006, management again announced that it would "go private" in a deal valued at $33 billion including the assumption of $11.7 billion in existing debt.

The approximate $21.3 billion purchase price for HCA's stock was financed by a combination of $12.8 billion in senior secured term loans of varying maturities and an estimated $8.5 billion in cash provided by Bain Capital, Merrill Lynch Global Private Equity, and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Company. HCA also would take out a $4 billion revolving credit line to satisfy immediate working capital requirements. The firm publicly announced a strategy of improving performance through growth rather than through cost cutting. HCA's network of 182 hospitals and 94 surgery centers is expected to benefit from an aging U.S. population and the resulting increase in health-care spending. The deal also seems to be partly contingent on the government assuming a larger share of health-care costs in the future. Finally, with many nonprofit hospitals faltering financially, HCA may be able to acquire them inexpensively.

While the longer-term trends in the health-care industry are unmistakable, shorter-term developments appear troublesome, including sluggish hospital admissions, more uninsured patients, and higher bad debt expenses. Moreover, with Medicare and Medicaid financially insolvent, it is unclear if future increases in government health-care spending would be sufficient to enable HCA investors to achieve their expected financial returns. With the highest operating profit margins in the industry, it is uncertain if HCA's cash flows could be significantly improved by cost cutting, if the revenue growth assumptions fail to materialize. HCA's management and equity investors have put themselves in a position in which they seem to have relatively little influence over the factors that directly affect the firm's future cash flows.

:

How did Time Warner's entry into the bidding affect pace of the negotiations and the relative bargaining power of MGM,Time Warner,and the Sony consortium?

HCA's LBO Represents a High-Risk Bet on Growth

While most LBOs are predicated on improving operating performance through a combination of aggressive cost cutting and revenue growth, HCA laid out an unconventional approach in its effort to take the firm private. On July 24, 2006, management again announced that it would "go private" in a deal valued at $33 billion including the assumption of $11.7 billion in existing debt.

The approximate $21.3 billion purchase price for HCA's stock was financed by a combination of $12.8 billion in senior secured term loans of varying maturities and an estimated $8.5 billion in cash provided by Bain Capital, Merrill Lynch Global Private Equity, and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Company. HCA also would take out a $4 billion revolving credit line to satisfy immediate working capital requirements. The firm publicly announced a strategy of improving performance through growth rather than through cost cutting. HCA's network of 182 hospitals and 94 surgery centers is expected to benefit from an aging U.S. population and the resulting increase in health-care spending. The deal also seems to be partly contingent on the government assuming a larger share of health-care costs in the future. Finally, with many nonprofit hospitals faltering financially, HCA may be able to acquire them inexpensively.

While the longer-term trends in the health-care industry are unmistakable, shorter-term developments appear troublesome, including sluggish hospital admissions, more uninsured patients, and higher bad debt expenses. Moreover, with Medicare and Medicaid financially insolvent, it is unclear if future increases in government health-care spending would be sufficient to enable HCA investors to achieve their expected financial returns. With the highest operating profit margins in the industry, it is uncertain if HCA's cash flows could be significantly improved by cost cutting, if the revenue growth assumptions fail to materialize. HCA's management and equity investors have put themselves in a position in which they seem to have relatively little influence over the factors that directly affect the firm's future cash flows.

:

How did Time Warner's entry into the bidding affect pace of the negotiations and the relative bargaining power of MGM,Time Warner,and the Sony consortium?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 98 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

63

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

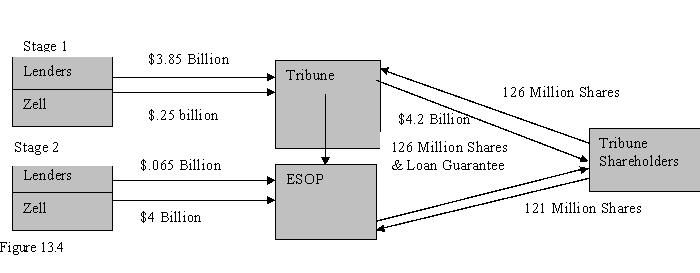

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4). Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

Is this transaction best characterized as a merger,acquisition,leveraged buyout,or spin-off? Explain your

answer.

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).

Tribune deal structure.

Tribune deal structure.The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.