Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133964612

Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133964612 Exercise 1

Emerging Markets: From Copycats to Innovators

The rise of emerging multinationals from emerging economies-think of Acer, BYD, Cemex, Embraer, Fox-conn, Geely, Goldwind, HTC, Lenovo, Mahindra, Suzlon, and Tata-has created tremendous buzz, fear, and disdain around the world. The fear comes from multinationals based in developed economies that are afraid of the disruption brought by this new breed of global competitors. The disdain stems from the characterization of these new multinationals as mere copycats that are good at imitating and bad at innovating.

Although multinationals from developed economies imitate each other all the time, their favorite bragging line is their focus on innovation. In contrast, firms from emerging economies openly confess that they are more interested in learning, which is to say that they are not ashamed of being copycats. In the West, a copycat is defined as one that closely imitates (and even mimics) another, and being a copycat is indicative of a lack of creativity. However, throughout emerging economies, being a copycat is indicative of a conscientious student who intimately learns from the master's every move. For firms in emerging economies, their masters have been good teachers in teaching basic moves. In search for low-cost solutions, Western firms have brought their original equipment manufacturers (OEM) up to speed -that was how Acer and Lenovo started. In the scramble prior to 2000 to fix the "millennium bug" (otherwise known as the "Y2K" problem), Western IT giants taught Indian firms such as TCS, Infosys, and Wipro a bag of tricks. About a decade ago, the conventional wisdom among Western firms was that firms in emerging economies would indeed become formidable low-cost providers of basic products and services, but as long as they remained behind in the innovation game, they would remain permanently behind leading Western firms. However, such conventional wisdom is now increasingly challenged.

Western firms' emphasis on innovation is consistent with traditional theory, which suggests that a firm's world-class competitive advantage stems from the innovations that it owns-the jargon is "ownership advantage." Owning such innovations allows the GEs, the Siemens, and the Hondas from the Triad to invest globally to teach the rest of the world how to make the stuff. However, a new breed of emerging multinationals has become active global competitors in the absence of such world-class capabilities. For example, in semiconductor wafer factories, Chinese technologies are at least two generations behind those of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. In internal-combustion engines, Chinese automakers are still 10 to 20 years behind global leaders. While Indian firms made great progress in IT/BPO, India's lackluster infrastructure seems to undermine the development of more advanced manufacturing and logistics industries.

So what are the core capabilities of the emerging multinationals? While debates rage, one school of thought points to their learning abilities. Learning is probably the most unusual aspect among many emerging multinationals. Instead of the "I-will-tell-you-what-to-do" mentality typical of old-line MNEs from developed economies, many emerging multinationals openly profess that they go abroad to learn. Tata expressed a strong interest in learning how to compete in developed economies with high-end products by acquiring Jaguar and Land Rover. Lenovo aspired to learn how to globalize its organization by purchasing IBM's PC division. Geely endeavored to learn to enhance automotive safety and branding capabilities by taking over Volvo.

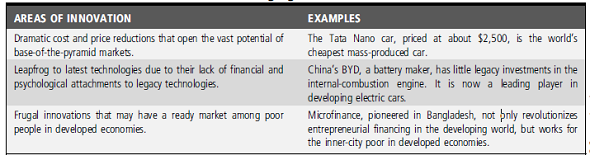

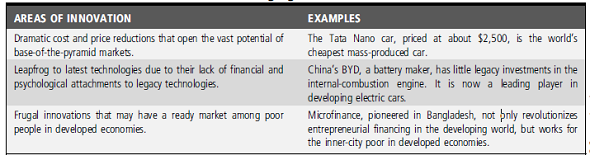

If you have watched any kung-fu movie (the most recent is Kung-Fu Panda), you will remember that a new champion cannot merely be an excellent student-at some point, the student will have to be a master himself by innovating some fancy moves. These moves are not likely to create head-to-head competition against existing masters. Rather, these innovators are likely to leverage their intimate knowledge of the needs and wants of customers in lower-income markets and package it with their learning from world-class competitors. Shown in Table 3.6, the results may be some "game-changing" or "paradigm-changing" innovations that decisively push advantage to the side of some (while certainly not all) emerging multinationals.

While scholars have long suggested that innovations do not necessarily have to be "high-tech," the hype about "innovation" centers around cutting-edge products and services-many executives and firms daydream about becoming the next Apple. Emerging multinationals tend to focus on "mid-tech" industries and thrive on their capabilities that unleash novel "affordability innovations." For old-line multinationals that traditionally develop high-tech and high-price innovations in developed economies and then manage to let these innovations "trickle down," the learning race now focuses on developing new products and services in emerging economies-known as "reverse innovations." GE's efforts to develop portable ultrasounds and ECG machines in China and India, respectively, represent some successful examples of these new experiments, which are necessitated by the emergence of innovative new multinationals that even the mighty GE has to take seriously (see Emerging Markets 1.2).

Sources: Based on (1) R. Chittoor, M. Sarkar, S. Ray, P. Aulakh, 2009, Third World copycats to emerging multinationals, Organization Science, 20: 187-205; (2) V. Govindarajan R. Ramamurti, 2011, Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global strategy, Global Strategy Journal, 1: 191-205; (3) Y. Luo, J. Sun, S. Wang, 2011, Emerging economy copycats, Academy of

TABLE 3.6 New Innovations from Emerging Multinationals

Management Perspectives, May: 37-56; (4) J. Mathews, 2006, Dragon multinationals as new features of globalization in the 21st century, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23: 5-27; (5) M. W. Peng, 2012, The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China, Global Strategy Journal, 2: 97-107; (6) M. W. Peng, R. Bhagat, S. Chang, 2010, Asia and global business, Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 373-376; (7) O. Shenkar, 2010, Copycats, Boston: Harvard Business School Press; (8) S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As, Journal of World Business, 47: 4-16.

What are the core resources and capabilities of emerging multinationals from emerging economies?

The rise of emerging multinationals from emerging economies-think of Acer, BYD, Cemex, Embraer, Fox-conn, Geely, Goldwind, HTC, Lenovo, Mahindra, Suzlon, and Tata-has created tremendous buzz, fear, and disdain around the world. The fear comes from multinationals based in developed economies that are afraid of the disruption brought by this new breed of global competitors. The disdain stems from the characterization of these new multinationals as mere copycats that are good at imitating and bad at innovating.

Although multinationals from developed economies imitate each other all the time, their favorite bragging line is their focus on innovation. In contrast, firms from emerging economies openly confess that they are more interested in learning, which is to say that they are not ashamed of being copycats. In the West, a copycat is defined as one that closely imitates (and even mimics) another, and being a copycat is indicative of a lack of creativity. However, throughout emerging economies, being a copycat is indicative of a conscientious student who intimately learns from the master's every move. For firms in emerging economies, their masters have been good teachers in teaching basic moves. In search for low-cost solutions, Western firms have brought their original equipment manufacturers (OEM) up to speed -that was how Acer and Lenovo started. In the scramble prior to 2000 to fix the "millennium bug" (otherwise known as the "Y2K" problem), Western IT giants taught Indian firms such as TCS, Infosys, and Wipro a bag of tricks. About a decade ago, the conventional wisdom among Western firms was that firms in emerging economies would indeed become formidable low-cost providers of basic products and services, but as long as they remained behind in the innovation game, they would remain permanently behind leading Western firms. However, such conventional wisdom is now increasingly challenged.

Western firms' emphasis on innovation is consistent with traditional theory, which suggests that a firm's world-class competitive advantage stems from the innovations that it owns-the jargon is "ownership advantage." Owning such innovations allows the GEs, the Siemens, and the Hondas from the Triad to invest globally to teach the rest of the world how to make the stuff. However, a new breed of emerging multinationals has become active global competitors in the absence of such world-class capabilities. For example, in semiconductor wafer factories, Chinese technologies are at least two generations behind those of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. In internal-combustion engines, Chinese automakers are still 10 to 20 years behind global leaders. While Indian firms made great progress in IT/BPO, India's lackluster infrastructure seems to undermine the development of more advanced manufacturing and logistics industries.

So what are the core capabilities of the emerging multinationals? While debates rage, one school of thought points to their learning abilities. Learning is probably the most unusual aspect among many emerging multinationals. Instead of the "I-will-tell-you-what-to-do" mentality typical of old-line MNEs from developed economies, many emerging multinationals openly profess that they go abroad to learn. Tata expressed a strong interest in learning how to compete in developed economies with high-end products by acquiring Jaguar and Land Rover. Lenovo aspired to learn how to globalize its organization by purchasing IBM's PC division. Geely endeavored to learn to enhance automotive safety and branding capabilities by taking over Volvo.

If you have watched any kung-fu movie (the most recent is Kung-Fu Panda), you will remember that a new champion cannot merely be an excellent student-at some point, the student will have to be a master himself by innovating some fancy moves. These moves are not likely to create head-to-head competition against existing masters. Rather, these innovators are likely to leverage their intimate knowledge of the needs and wants of customers in lower-income markets and package it with their learning from world-class competitors. Shown in Table 3.6, the results may be some "game-changing" or "paradigm-changing" innovations that decisively push advantage to the side of some (while certainly not all) emerging multinationals.

While scholars have long suggested that innovations do not necessarily have to be "high-tech," the hype about "innovation" centers around cutting-edge products and services-many executives and firms daydream about becoming the next Apple. Emerging multinationals tend to focus on "mid-tech" industries and thrive on their capabilities that unleash novel "affordability innovations." For old-line multinationals that traditionally develop high-tech and high-price innovations in developed economies and then manage to let these innovations "trickle down," the learning race now focuses on developing new products and services in emerging economies-known as "reverse innovations." GE's efforts to develop portable ultrasounds and ECG machines in China and India, respectively, represent some successful examples of these new experiments, which are necessitated by the emergence of innovative new multinationals that even the mighty GE has to take seriously (see Emerging Markets 1.2).

Sources: Based on (1) R. Chittoor, M. Sarkar, S. Ray, P. Aulakh, 2009, Third World copycats to emerging multinationals, Organization Science, 20: 187-205; (2) V. Govindarajan R. Ramamurti, 2011, Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global strategy, Global Strategy Journal, 1: 191-205; (3) Y. Luo, J. Sun, S. Wang, 2011, Emerging economy copycats, Academy of

TABLE 3.6 New Innovations from Emerging Multinationals

Management Perspectives, May: 37-56; (4) J. Mathews, 2006, Dragon multinationals as new features of globalization in the 21st century, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23: 5-27; (5) M. W. Peng, 2012, The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China, Global Strategy Journal, 2: 97-107; (6) M. W. Peng, R. Bhagat, S. Chang, 2010, Asia and global business, Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 373-376; (7) O. Shenkar, 2010, Copycats, Boston: Harvard Business School Press; (8) S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As, Journal of World Business, 47: 4-16.

What are the core resources and capabilities of emerging multinationals from emerging economies?

Explanation

Core resources and capabilities in an em...

Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255