Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133964612

Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133964612 Exercise 5

Emerging Markets: Emerging Acquirers from China and India

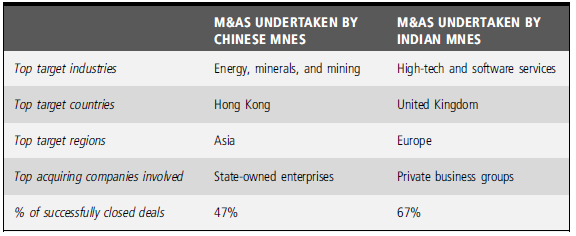

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from emerging economies, especially from China and India, have emerged as a new breed of acquirers around the world. Causing "oohs" and "ahhs," they have grabbed media headlines and caused controversies. Anecdotes aside, are the patterns of these new global acquirers similar? How do they differ? Only recently has rigorous academic research been conducted to allow for systematic comparison (Table 9.6).

Overall, China's stock of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) (1.5% of the worldwide total) is about three times India's (0.5%). A visible similarity is that both Chinese and Indian MNEs seem to primarily use M As as their primary mode of OFDI. Throughout the 2000s, Chinese firms spent $130 billion to engage in M As overseas, whereas Indian firms made M A deals worth $60 billion.

From an industry-based view, it is clear that MNEs from China and India have targeted industries to support and strengthen their own most competitive industries at home. Given China's prowess in manufacturing industries at home, Chinese firms' overseas M As have primarily targeted energy, minerals, and mining-crucial supply industries that feed their manufacturing operations. Indian MNEs' world-class leadership position in high-tech and software services is reflected in their interest in acquiring firms in these industries.

The geographic spread of these MNEs is indicative of the level of their capabilities. Chinese firms have undertaken most of their deals in Asia, with Hong Kong being their most favorable location. In other words, the geographic distribution of Chinese M As is not global; rather, it is quite regional. This reflects a relative lack of capabilities to engage in managerial challenges in regions distant from China, especially in more developed economies. Indian MNEs have primarily made deals in Europe, with the United Kingdom as the leading target country. For example, acquisitions made by Tata Motors (Jaguar and Land Rover) and Tata Steel (Corus Group) propelled Tata Group to become the number one private-sector employer in the UK. Overall, Indian firms display a more global spread in their M As, and a higher level of confidence and sophistication in making deals in developed economies.

TABLE 9.6 Comparing Cross-Border M As Undertaken by Chinese and Indian MNEs

Source: Extracted from S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs, Journal of World Business, 47(1): 4-16.

From an institution-based view, the contrasts between the leading Chinese and Indian acquirers are significant. The primary M A players from China are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which have their own advantages (such as strong support from the Chinese government) and trappings (such as resentment and suspicion from host country governments). The movers and shakers of overseas M As from India are private business groups, which generally are not viewed with strong suspicion. The limited evidence suggests that M As by Indian firms tend to create value for their shareholders. On the other hand, M As by Chinese firms tend to destroy value for their shareholders-indicative of potential hubris and managerial motives evidenced by empire building and agency problems.

Announcing high-profile deals is one thing, but completing them is another matter. Chinese MNEs have particularly poor records in completing the overseas acquisition deals they announce. Only less than half (47%) of the acquisitions announced by Chinese MNEs were completed, which compares unfavorably to Indian MNEs' 67% completion rate. Chinese MNEs' lack of ability and experience in due diligence and financing is one reason, but another reason is the political backlash and resistance they encounter, especially in developed economies. The 2005 failure of CNOOC's bid for Unocal in the United States and the 2009 failure of Chinalco's bid for Rio Tinto's assets in Australia are but two high-profile examples.

Even assuming successful completion, integration is a leading challenge during the post-acquisition phase. Both Chinese and Indian firms seem to suffer from these challenges. Tata, for example, was famously clawed by Jaguar. In general, acquirers from China and India have often taken the "high road" to acquisitions, in which acquirers deliberately allow acquired target companies to retain autonomy, keep the top management intact, and then gradually encourage interaction between the two sides. In contrast, the "low road" to acquisitions would be for acquirers to act quickly to impose their systems and rules on acquired target companies. Although the "high road" sounds noble, this is a reflection of these acquirers' lack of international management experience and capabilities.

Sources: Based on (1) Y. Chen M. Young, 2010, Crossborder M As by Chinese listed companies, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , 27: 523-539; (2) L. Cui F. Jiang, 2010, Behind ownership decision of Chinese outward FDI, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , 27: 751-774; (3) P. Deng, 2009, Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion? Journal of World Business , 44: 74-84; (4) S. Gubbi, P. Aulakh, S. Ray, M. Sarkar, R. Chittoor, 2010, Do international acquisitions by emerging economy firms create shareholder value? Journal of International Business Studies , 41: 397-418; (5) M. W. Peng, 2012, The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China, Global Strategy Journal, 2: 97-107; (6) M. W. Peng, 2012, Why China's investments aren't a threat, Harvard Business Review , February: blogs.hbr.org; (7) H. Rui G. Yip, 2008, Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms, Journal of World Business , 43: 213-226; (8) S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs, Journal of World Business , 47(1): 4-16.

Drawing on industry-based, resource-based, and institution-based views, outline the similarities and differences between Chinese and Indian multinational acquirers.

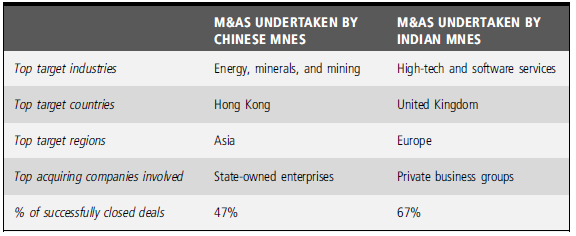

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from emerging economies, especially from China and India, have emerged as a new breed of acquirers around the world. Causing "oohs" and "ahhs," they have grabbed media headlines and caused controversies. Anecdotes aside, are the patterns of these new global acquirers similar? How do they differ? Only recently has rigorous academic research been conducted to allow for systematic comparison (Table 9.6).

Overall, China's stock of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) (1.5% of the worldwide total) is about three times India's (0.5%). A visible similarity is that both Chinese and Indian MNEs seem to primarily use M As as their primary mode of OFDI. Throughout the 2000s, Chinese firms spent $130 billion to engage in M As overseas, whereas Indian firms made M A deals worth $60 billion.

From an industry-based view, it is clear that MNEs from China and India have targeted industries to support and strengthen their own most competitive industries at home. Given China's prowess in manufacturing industries at home, Chinese firms' overseas M As have primarily targeted energy, minerals, and mining-crucial supply industries that feed their manufacturing operations. Indian MNEs' world-class leadership position in high-tech and software services is reflected in their interest in acquiring firms in these industries.

The geographic spread of these MNEs is indicative of the level of their capabilities. Chinese firms have undertaken most of their deals in Asia, with Hong Kong being their most favorable location. In other words, the geographic distribution of Chinese M As is not global; rather, it is quite regional. This reflects a relative lack of capabilities to engage in managerial challenges in regions distant from China, especially in more developed economies. Indian MNEs have primarily made deals in Europe, with the United Kingdom as the leading target country. For example, acquisitions made by Tata Motors (Jaguar and Land Rover) and Tata Steel (Corus Group) propelled Tata Group to become the number one private-sector employer in the UK. Overall, Indian firms display a more global spread in their M As, and a higher level of confidence and sophistication in making deals in developed economies.

TABLE 9.6 Comparing Cross-Border M As Undertaken by Chinese and Indian MNEs

Source: Extracted from S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs, Journal of World Business, 47(1): 4-16.

From an institution-based view, the contrasts between the leading Chinese and Indian acquirers are significant. The primary M A players from China are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which have their own advantages (such as strong support from the Chinese government) and trappings (such as resentment and suspicion from host country governments). The movers and shakers of overseas M As from India are private business groups, which generally are not viewed with strong suspicion. The limited evidence suggests that M As by Indian firms tend to create value for their shareholders. On the other hand, M As by Chinese firms tend to destroy value for their shareholders-indicative of potential hubris and managerial motives evidenced by empire building and agency problems.

Announcing high-profile deals is one thing, but completing them is another matter. Chinese MNEs have particularly poor records in completing the overseas acquisition deals they announce. Only less than half (47%) of the acquisitions announced by Chinese MNEs were completed, which compares unfavorably to Indian MNEs' 67% completion rate. Chinese MNEs' lack of ability and experience in due diligence and financing is one reason, but another reason is the political backlash and resistance they encounter, especially in developed economies. The 2005 failure of CNOOC's bid for Unocal in the United States and the 2009 failure of Chinalco's bid for Rio Tinto's assets in Australia are but two high-profile examples.

Even assuming successful completion, integration is a leading challenge during the post-acquisition phase. Both Chinese and Indian firms seem to suffer from these challenges. Tata, for example, was famously clawed by Jaguar. In general, acquirers from China and India have often taken the "high road" to acquisitions, in which acquirers deliberately allow acquired target companies to retain autonomy, keep the top management intact, and then gradually encourage interaction between the two sides. In contrast, the "low road" to acquisitions would be for acquirers to act quickly to impose their systems and rules on acquired target companies. Although the "high road" sounds noble, this is a reflection of these acquirers' lack of international management experience and capabilities.

Sources: Based on (1) Y. Chen M. Young, 2010, Crossborder M As by Chinese listed companies, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , 27: 523-539; (2) L. Cui F. Jiang, 2010, Behind ownership decision of Chinese outward FDI, Asia Pacific Journal of Management , 27: 751-774; (3) P. Deng, 2009, Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion? Journal of World Business , 44: 74-84; (4) S. Gubbi, P. Aulakh, S. Ray, M. Sarkar, R. Chittoor, 2010, Do international acquisitions by emerging economy firms create shareholder value? Journal of International Business Studies , 41: 397-418; (5) M. W. Peng, 2012, The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China, Global Strategy Journal, 2: 97-107; (6) M. W. Peng, 2012, Why China's investments aren't a threat, Harvard Business Review , February: blogs.hbr.org; (7) H. Rui G. Yip, 2008, Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms, Journal of World Business , 43: 213-226; (8) S. Sun, M. W. Peng, B. Ren, D. Yan, 2012, A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs, Journal of World Business , 47(1): 4-16.

Drawing on industry-based, resource-based, and institution-based views, outline the similarities and differences between Chinese and Indian multinational acquirers.

Explanation

The below mentioned are the similarities...

Global Strategy 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255