Introduction to Psychology 10th Edition by Rod Plotnik,Haig Kouyoumdjian

Edition 10ISBN: 978-1133939535

Introduction to Psychology 10th Edition by Rod Plotnik,Haig Kouyoumdjian

Edition 10ISBN: 978-1133939535 Exercise 10

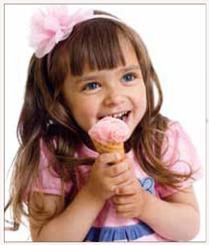

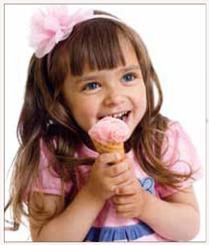

Can Phony Memories Change Your Behavior?

It's been well established that people can be made to believe "fake" memories, but can "fake" memories change people's behavior? Research psychologist Elizabeth Loftus of the University of California-Irvine and her colleagues studied whether simply suggesting food preferences can change what people decide to eat. To answer this question, these researchers asked college-aged participants to complete questionnaires on their personalities and food experiences. As part of the questionnaires, the participants were asked about childhood food experiences, such as whether they "ate a piece of banana cream pie." One week after completing the questionnaires, participants returned and were told that their responses were used to create a "unique" profile of their early childhood food experiences. Everyone's profile included generic statements such as they disliked spinach, enjoyed eating bananas, and felt happy when a classmate brought sweets to school. In addition, the profiles of one group of participants included one completely made-up point: "Felt ill after eating strawberry ice cream." The remaining participants were the control group and their profiles did not include a statement about getting ill as a result of eating strawberry ice cream. When participants in the false memory group were told the questionnaire results showed they had a bad childhood experience with strawberry ice cream, researchers asked several follow-up questions about the phony memory, such as where they were when they got sick and who else witnessed the event. About 41% of participants given the false memory believed they had once gotten sick from eating strawberry ice cream. Some of them even reported details about the experience such as "may have gotten sick after eating seven cups of ice cream." During this same visit, participants completed a second questionnaire about eating preferences, and many of these "believers" (20 of the 47) now reported less preference for and less willingness to eat strawberry ice cream. In contrast, the control group, who did not receive false feedback, did not show any change in their preference for strawberry ice cream. As many people have learned, a strong and long-lasting aversion to a certain food can develop after only one bad childhood experience. Loftus gives an example that a novel food such as béarnaise sauce may make a person sick one time and lead to avoiding the food in the future. The current study suggests it is possible for such an aversion to occur based only on a false memory. Loftus and her colleagues are now examining whether false memories of really liking certain healthy vegetables during childhood can be implanted and make people more likely to eat such foods as adults.

Question

Why were researchers able to implant false memories in these people?

It's been well established that people can be made to believe "fake" memories, but can "fake" memories change people's behavior? Research psychologist Elizabeth Loftus of the University of California-Irvine and her colleagues studied whether simply suggesting food preferences can change what people decide to eat. To answer this question, these researchers asked college-aged participants to complete questionnaires on their personalities and food experiences. As part of the questionnaires, the participants were asked about childhood food experiences, such as whether they "ate a piece of banana cream pie." One week after completing the questionnaires, participants returned and were told that their responses were used to create a "unique" profile of their early childhood food experiences. Everyone's profile included generic statements such as they disliked spinach, enjoyed eating bananas, and felt happy when a classmate brought sweets to school. In addition, the profiles of one group of participants included one completely made-up point: "Felt ill after eating strawberry ice cream." The remaining participants were the control group and their profiles did not include a statement about getting ill as a result of eating strawberry ice cream. When participants in the false memory group were told the questionnaire results showed they had a bad childhood experience with strawberry ice cream, researchers asked several follow-up questions about the phony memory, such as where they were when they got sick and who else witnessed the event. About 41% of participants given the false memory believed they had once gotten sick from eating strawberry ice cream. Some of them even reported details about the experience such as "may have gotten sick after eating seven cups of ice cream." During this same visit, participants completed a second questionnaire about eating preferences, and many of these "believers" (20 of the 47) now reported less preference for and less willingness to eat strawberry ice cream. In contrast, the control group, who did not receive false feedback, did not show any change in their preference for strawberry ice cream. As many people have learned, a strong and long-lasting aversion to a certain food can develop after only one bad childhood experience. Loftus gives an example that a novel food such as béarnaise sauce may make a person sick one time and lead to avoiding the food in the future. The current study suggests it is possible for such an aversion to occur based only on a false memory. Loftus and her colleagues are now examining whether false memories of really liking certain healthy vegetables during childhood can be implanted and make people more likely to eat such foods as adults.

Question

Why were researchers able to implant false memories in these people?

Explanation

Some of the memory researchers make, peo...

Introduction to Psychology 10th Edition by Rod Plotnik,Haig Kouyoumdjian

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255