Global Business 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133485933

Global Business 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1133485933 Exercise 71

Confronting significant liabilities of foreignness, the Sino Iron project in Australia experienced a great deal of delays and cost overruns. What could the management team do to better engage stakeholders in the host country?

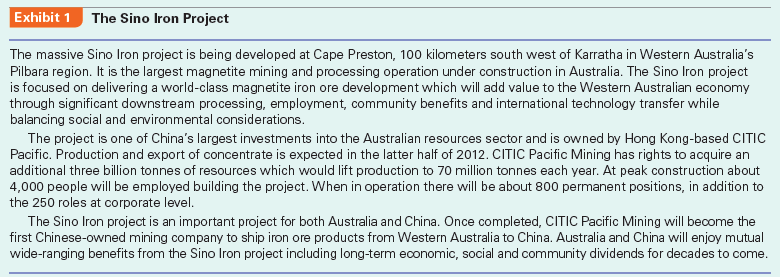

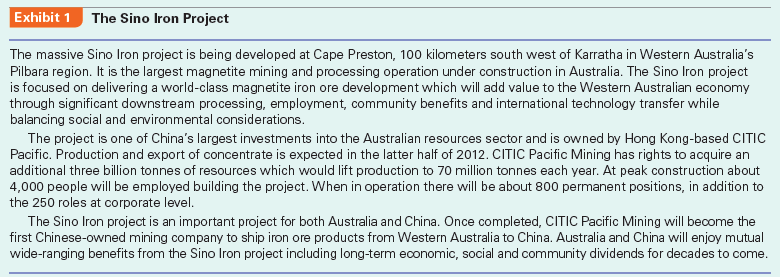

The Sino Iron Project

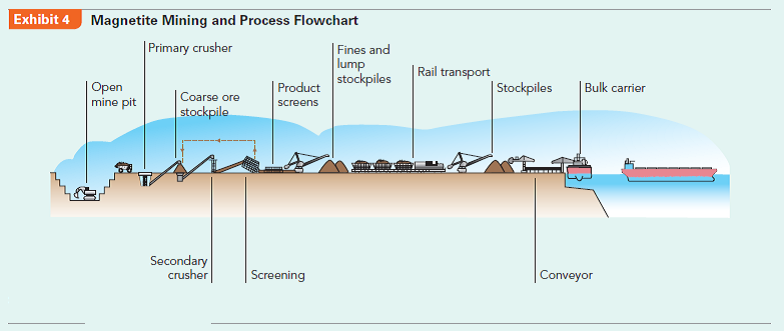

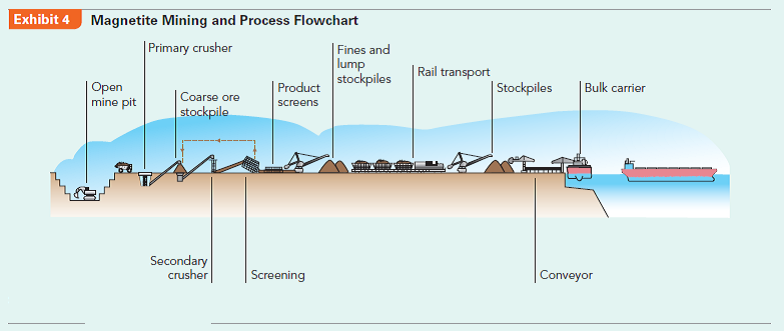

In January 2010, Hua Dongyi rushed to assume his duty as Chairman of Sino Iron Pty Ltd. (Australia) in Perth, the capital and largest city in Western Australia. The parent company of Sino Iron, China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC), just transferred him from CITIC Construction Co., a subsidiary focused on infrastructural projects in Africa and Asia, to Sino Iron in Australia. The massive Sino Iron project was the largest magnetite mining and processing operation under construction in Australia, and was one of China's largest investments into the Australian resources sector (see Exhibits 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Hua had an urgent meeting with his management team. Sino Iron faced tremendous challenges: Spotting the high potential demand for iron ores in China, CITIC had purchased the mining license of Australian magnetite iron ores, and started the project in 2007. After investing A$1.6 billion, the project had suffered significant delays and cost overruns, pushing back the planned date of operation from the first half of 2009 to early 2011, and now even that date was not realistic.2 The challenge for Hua and his team was to push the project forward and launch operations soon.

The global price of iron ores changed dramatically. In 2010, negotiations broke down between China Steel Association and the world's three biggest mining companies- BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, and Vale of Brazil. Some Chinese steel companies had to accept a nearly 100% price increase of iron ore imports from these three mining giants and quarterly price adjustments. After the recent price hike, a correction could be due any time and price could fall drastically later, which would be bad timing for Sino Iron if production was further delayed. Furthermore, magnetite iron ores due

to their nature had a 40% higher production cost than other premium resources mainly under the control of BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, which never allowed joint investment with Chinese companies. This could put Sino Iron in a very disadvantaged position if it found price dropping after its mine started operating.

Sino Iron's CEO Barry Fitzgerald was a local guy with 30 years of experience in iron ore operations. While he reported to Hua, he was not responsible for the delay and cost overruns. The main reason was the unexpectedly long time of approval procedures from the government. Delay meant higher labor costs-the cost of prospecting would increase another US$350 million from the original plan of US$3.5 billion.

However, Hua did not trust the local managers very well, because they were still leaving work every day on regular time, taking vacations, and expecting the bonus at the end of the year. Sometimes engineers were in the middle of processing concretes and as soon as it was time to go home, they would leave work without worrying whether it would cause problems. When there were problems, they would try to blame each other, and the sense of belonging and loyalty typical in Chinese firms was nowhere to be found here.

At the end of 2009, during the wave of acquisitions in Australia by Chinese steel companies, the Australian people's resistance and hostility to Chinese companies increased suddenly. Once, an Australian employee blurted out that after all, this was all the Chinese government's money so why should he care. Hua got upset: "Our parent company, CITIC Pacific, is a public company in Hong Kong. The Chinese government is only one of many shareholders, and there are also other investors. I represent all the investors!"

In order to control the progress of the project, Hua had to have some capable Chinese managers working for him. From the end of 2009 to January 2010, four of his old subordinates from CITIC Construction came to his rescue in Perth. However, Hua and his management team still faced significant challenges in dealing with different stakeholders in Australia (Exhibit 5).

Government Relationship

In recent years, many Chinese companies began to invest in Australian mines. For example, Yanzhou Coal Enterprise acquired Australia Felix. Sichuan Hanlong invested US$200 million into a Molybdenum mine in Australia. Chongqing Iron Steel Group acquired the Asian Iron and Steel holding company, which was in control of Australian iron ore in Istanbul Xin. China Minmetals Corporation acquired some assets of Australia OZ Minerals for US$1.34 billion.

Overall, the Australian government has been open to these acquisitions. Yet it has also been on the alert to the acquirers that mostly have a government background, concerned that these companies may try to reduce taxes to the Australian government through internal transfer pricing, diminish local employment opportunities, and affect the local environment. Thus, the Australian government has tightened regulations. For example, the Australian Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) required China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group to reduce its stake during its acquisition of Lynas, which led to the failure of the acquisition. China Alumni Corporation's acquisition of Rio Tinto also failed due to the extended review of FIRB, which led to the opposition of other stakeholders.

At the same time, since Australia's premium iron ore resources are mainly under the control of BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, Chinese companies, as late comers, can only invest in those magnetite iron ores that have a 40% higher production cost. For example, Australia's third largest iron ore producer, FMG, never agreed to joint investment with Chinese companies, thinking it was not worthwhile to give the foreign side shares. But FMG would seek Chinese shares in magnetite iron ore projects. The reason that CITIC and Chongqing Iron Steel Group's acquisitions received the approval from FIRB and that they were able to acquire 100% of the shares was exactly due to the fact that the production cost and risk of magnetite iron ores were too high. Local Australian firms did not want to touch these high-risk projects.

Hua Dongyi's interactions with the Australian government were forceful but did not have much effect. In Africa, CITIC can leverage its state ownership background and obtain much support from the local government with a lot of preferential treatment. However, in Australia, the state ownership background of CITIC has not brought any benefits in interactions with the Australian government. On the contrary, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and their subsidiaries can easily be regarded as agents of foreign governments and may be viewed as threats to national security.

On May 2, 2010, the Australian government announced that it would exact a 40% Resource Super Profits Tax (RSPT) on mining firms starting in July 2012, in order to pay for the increasingly higher cost of infrastructure investment and pensions. The new tax encouraged more exploration and mergers and acquisitions (M As) within policy constraints. Sino Iron could gain some competitive advantage over BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto for the resource tax, because the new tax would allow companies to deduct the book value of inventory assets during the first five years of the new tax.

Labor and Contractor Relationship

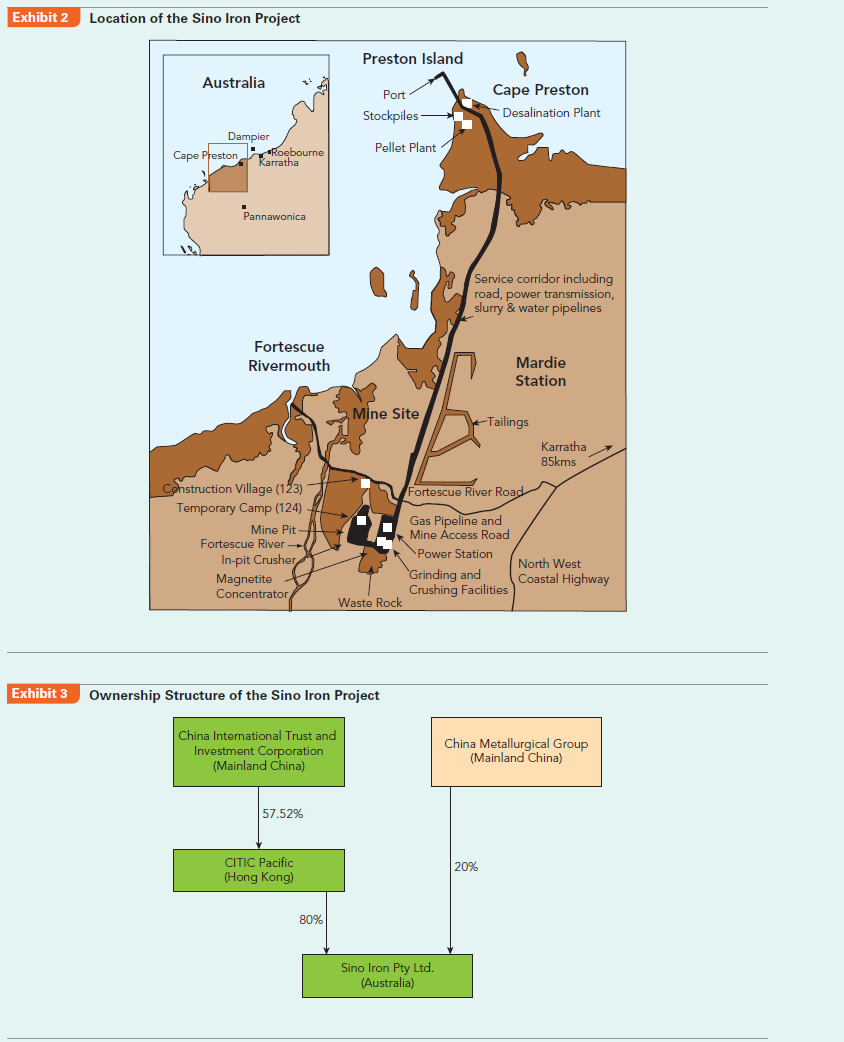

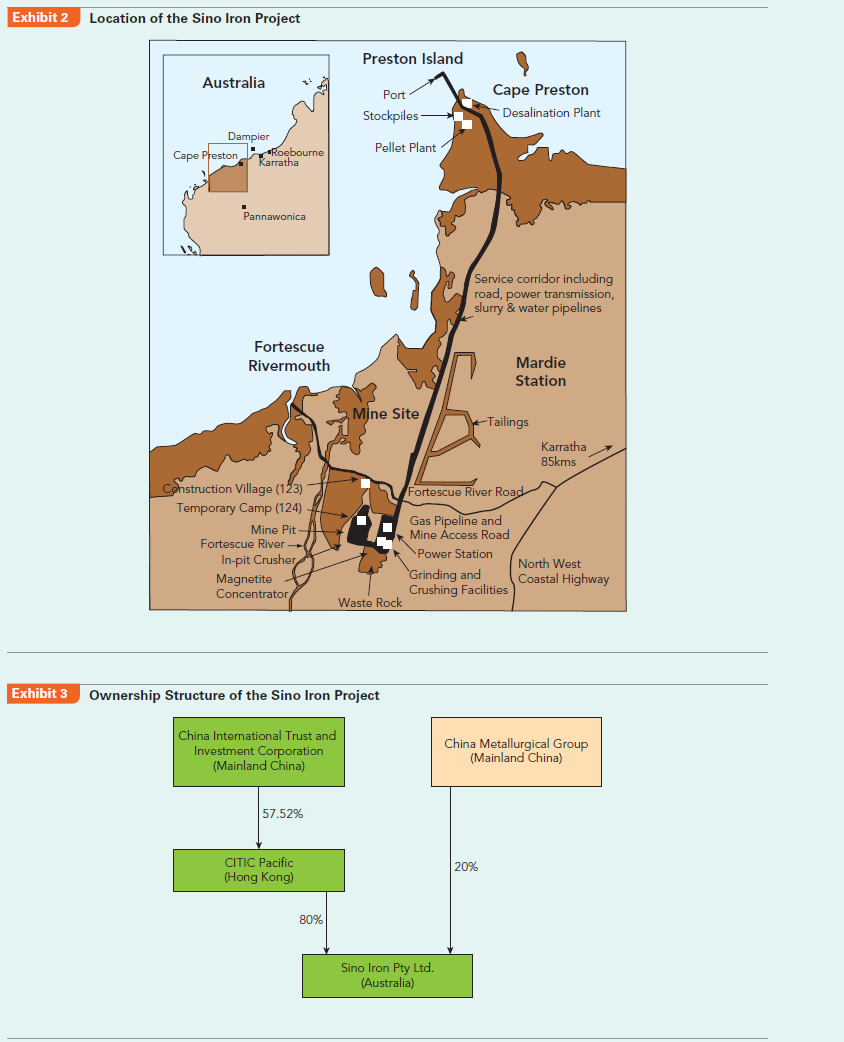

The Sino Iron project is located in the northwestern corner of Australia, occupying an area of 25 square kilometers (Exhibit 2). Looking from the airplane, it is an area of flat brown earth with few trees and not many people. The mine is 100 kilometers from the closest town Karratha, and a one-night stay in a motel there is even more expensive than a five-star hotel in Sydney. The only function of the town is to provide a point of transit for the nearby mine workers to go from and back to Perth.

A prosperous mining industry led to high demand for labor, and the result is that a mine worker in Western Australia typically has an annual salary of over A$100,000, approximately the level of Australian university professors and twice the average income of Australians. A regular excavator driver can make A$160,000. Even a cleaner in the mining area can make A$80,000. Depending on the type of work, some workers can rest a week out of every three weeks, and some every two weeks. The company pays for their airfare if they go back home during vacation. Furthermore, due to the high demand from China and the start-up of many large resource projects, competition for labor has increased with many mine workers threatening to switch companies if denied a raise.

Sino Iron and its engineering contractor China Metallurgical Group used to assume that they could transport a large batch of capable (and low-cost) workers from China and rapidly move the project along. However, worker visas became a serious problem. Despite the lobbying of both the companies and the Chinese government, only several hundred visas were issued. Yet, the Australian government required all workers to pass a certification in English, which almost made it impossible for all the workers ready to come.

"If our workers can score a 7 in IELTS (International English Language Testing System), they would not be coming here," Hua Dongyi sighed helplessly. Not only did the Chinese mine workers fail to come, the chefs that CITIC found to cater to the Chinese tastes of their managers could not get visas either. "We have found three chefs successfully, and none of them can get a visa." Now the Chinese managers could only cook for themselves after work in the apartments that they rented.

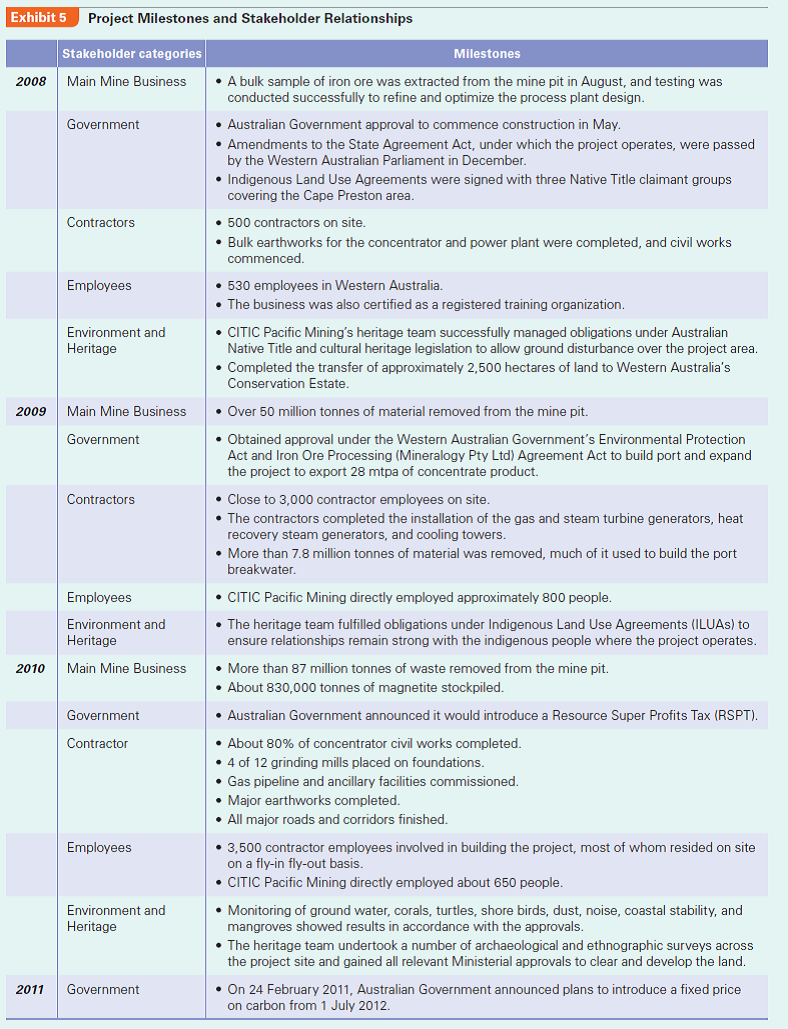

In order to save labor costs, the project used the world's biggest and most powerful rod mill, the world's largest wheel loader, and the world's largest excavator- with a price tag of US$19 million and a capacity of 1000 tonnes each time. This also promoted the development of China's domestic equipment industry. For example, CITIC Pacific's sister company CITIC Heavy Industries developed a large-scale mining rod mill, which could increase mining abilities by 40% and reduce resource consumption by 20%. Such equipment thus could fully utilize low-grade iron ores and increase the mining efficiency greatly.

Community Relations

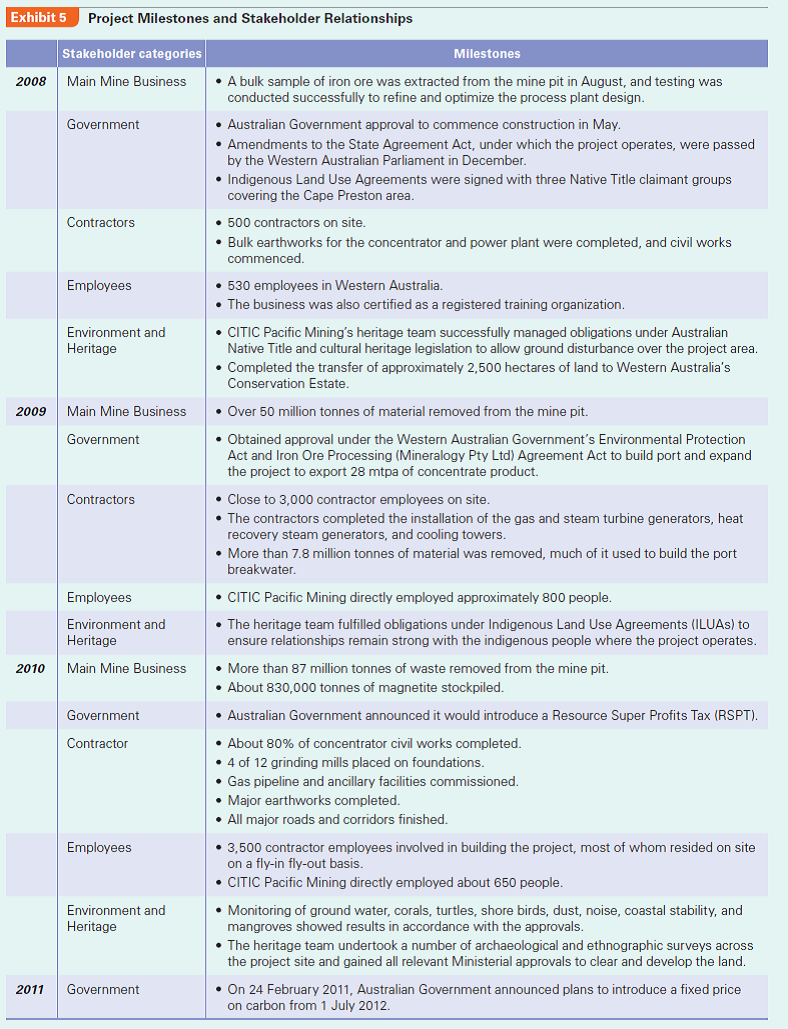

"Even though Australia is a developed country, this area is the countryside. In many ways it is not even as good as Africa." This was Hua Dongyi's first impression after arriving at the project site. CITIC Pacific had to invest a great deal in infrastructure. Since the project started in August 2006, billions of dollars have already been invested in the mineral processing plant, pellet plant, slurry pipeline, port facilities, power plant, and desalination plant (see Exhibit 4). One Chinese manager joked, "Usually you would feel more accomplished when you construct things and are able to see the effect. But here it seems that even though you have invested hundreds of thousands of dollars, there is still not much difference." What the Chinese manager did not comment on was that these infrastructure investments could not be taken away, so after the end of the 25-year mining period, they would be given to the locals for free.

Sino Iron also established a team to deal with historical remains, and did a series of explorations on the project site. In 2009, Sino Iron obtained various permits on land development and utilization. With these permits and proper care of historical remains, Sino Iron was able to enter the whole area on the project site, which enabled the smooth operation of construction. The historical remains team also abided by the obligations as listed in the Indigenous Land Use Agreements and ensured the close relationship between the project and the aboriginals living in the area.

Sino Iron also obtained various environmental permits critical to the progress of the project and its future expansion. During the process, the environmental team monitored the underground water, animals in caves, and sea turtles and birds on land. It also audited the environmental performance of its contractor in order to ensure the protection of the natural environment.

By March 2010, Hua had obtained all the key government permits and approvals regarding the environment and historical remains, yet he also began to worry about the cost increases they would bring. A twohole bridge, which would cost about 5 million yuan (about A$800,000) in China, ended up costing over A$50 million since it used steel pipe pile to protect the local environment. The cost differences were incredible. Moreover, many other things drove him crazy. For example, during meetings, usually the first two hours would be spent not discussing issues about the project, but rather environmental protection. For example, if a hole was left in the mining area, would it be necessary to build a ladder in case animals fell into the hole and could not climb up? If they built a two-hole bridge near the dock and there were people working under the bridge, would that disturb the ecological environment of crabs near the seawall?

All of these certainly increased the project's various costs, and were unforeseen before the investment. It appears that when undertaking overseas investments, Chinese managers need to put different priorities on different issues and stakeholders. Things that are easy to deal with in China are often difficult in other countries, and vice versa.

Case Discussion Questions

Who are the stakeholders in the Sino Iron project? How can the Chinese company best engage them?

The Sino Iron Project

In January 2010, Hua Dongyi rushed to assume his duty as Chairman of Sino Iron Pty Ltd. (Australia) in Perth, the capital and largest city in Western Australia. The parent company of Sino Iron, China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC), just transferred him from CITIC Construction Co., a subsidiary focused on infrastructural projects in Africa and Asia, to Sino Iron in Australia. The massive Sino Iron project was the largest magnetite mining and processing operation under construction in Australia, and was one of China's largest investments into the Australian resources sector (see Exhibits 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Hua had an urgent meeting with his management team. Sino Iron faced tremendous challenges: Spotting the high potential demand for iron ores in China, CITIC had purchased the mining license of Australian magnetite iron ores, and started the project in 2007. After investing A$1.6 billion, the project had suffered significant delays and cost overruns, pushing back the planned date of operation from the first half of 2009 to early 2011, and now even that date was not realistic.2 The challenge for Hua and his team was to push the project forward and launch operations soon.

The global price of iron ores changed dramatically. In 2010, negotiations broke down between China Steel Association and the world's three biggest mining companies- BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, and Vale of Brazil. Some Chinese steel companies had to accept a nearly 100% price increase of iron ore imports from these three mining giants and quarterly price adjustments. After the recent price hike, a correction could be due any time and price could fall drastically later, which would be bad timing for Sino Iron if production was further delayed. Furthermore, magnetite iron ores due

to their nature had a 40% higher production cost than other premium resources mainly under the control of BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, which never allowed joint investment with Chinese companies. This could put Sino Iron in a very disadvantaged position if it found price dropping after its mine started operating.

Sino Iron's CEO Barry Fitzgerald was a local guy with 30 years of experience in iron ore operations. While he reported to Hua, he was not responsible for the delay and cost overruns. The main reason was the unexpectedly long time of approval procedures from the government. Delay meant higher labor costs-the cost of prospecting would increase another US$350 million from the original plan of US$3.5 billion.

However, Hua did not trust the local managers very well, because they were still leaving work every day on regular time, taking vacations, and expecting the bonus at the end of the year. Sometimes engineers were in the middle of processing concretes and as soon as it was time to go home, they would leave work without worrying whether it would cause problems. When there were problems, they would try to blame each other, and the sense of belonging and loyalty typical in Chinese firms was nowhere to be found here.

At the end of 2009, during the wave of acquisitions in Australia by Chinese steel companies, the Australian people's resistance and hostility to Chinese companies increased suddenly. Once, an Australian employee blurted out that after all, this was all the Chinese government's money so why should he care. Hua got upset: "Our parent company, CITIC Pacific, is a public company in Hong Kong. The Chinese government is only one of many shareholders, and there are also other investors. I represent all the investors!"

In order to control the progress of the project, Hua had to have some capable Chinese managers working for him. From the end of 2009 to January 2010, four of his old subordinates from CITIC Construction came to his rescue in Perth. However, Hua and his management team still faced significant challenges in dealing with different stakeholders in Australia (Exhibit 5).

Government Relationship

In recent years, many Chinese companies began to invest in Australian mines. For example, Yanzhou Coal Enterprise acquired Australia Felix. Sichuan Hanlong invested US$200 million into a Molybdenum mine in Australia. Chongqing Iron Steel Group acquired the Asian Iron and Steel holding company, which was in control of Australian iron ore in Istanbul Xin. China Minmetals Corporation acquired some assets of Australia OZ Minerals for US$1.34 billion.

Overall, the Australian government has been open to these acquisitions. Yet it has also been on the alert to the acquirers that mostly have a government background, concerned that these companies may try to reduce taxes to the Australian government through internal transfer pricing, diminish local employment opportunities, and affect the local environment. Thus, the Australian government has tightened regulations. For example, the Australian Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) required China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group to reduce its stake during its acquisition of Lynas, which led to the failure of the acquisition. China Alumni Corporation's acquisition of Rio Tinto also failed due to the extended review of FIRB, which led to the opposition of other stakeholders.

At the same time, since Australia's premium iron ore resources are mainly under the control of BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, Chinese companies, as late comers, can only invest in those magnetite iron ores that have a 40% higher production cost. For example, Australia's third largest iron ore producer, FMG, never agreed to joint investment with Chinese companies, thinking it was not worthwhile to give the foreign side shares. But FMG would seek Chinese shares in magnetite iron ore projects. The reason that CITIC and Chongqing Iron Steel Group's acquisitions received the approval from FIRB and that they were able to acquire 100% of the shares was exactly due to the fact that the production cost and risk of magnetite iron ores were too high. Local Australian firms did not want to touch these high-risk projects.

Hua Dongyi's interactions with the Australian government were forceful but did not have much effect. In Africa, CITIC can leverage its state ownership background and obtain much support from the local government with a lot of preferential treatment. However, in Australia, the state ownership background of CITIC has not brought any benefits in interactions with the Australian government. On the contrary, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and their subsidiaries can easily be regarded as agents of foreign governments and may be viewed as threats to national security.

On May 2, 2010, the Australian government announced that it would exact a 40% Resource Super Profits Tax (RSPT) on mining firms starting in July 2012, in order to pay for the increasingly higher cost of infrastructure investment and pensions. The new tax encouraged more exploration and mergers and acquisitions (M As) within policy constraints. Sino Iron could gain some competitive advantage over BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto for the resource tax, because the new tax would allow companies to deduct the book value of inventory assets during the first five years of the new tax.

Labor and Contractor Relationship

The Sino Iron project is located in the northwestern corner of Australia, occupying an area of 25 square kilometers (Exhibit 2). Looking from the airplane, it is an area of flat brown earth with few trees and not many people. The mine is 100 kilometers from the closest town Karratha, and a one-night stay in a motel there is even more expensive than a five-star hotel in Sydney. The only function of the town is to provide a point of transit for the nearby mine workers to go from and back to Perth.

A prosperous mining industry led to high demand for labor, and the result is that a mine worker in Western Australia typically has an annual salary of over A$100,000, approximately the level of Australian university professors and twice the average income of Australians. A regular excavator driver can make A$160,000. Even a cleaner in the mining area can make A$80,000. Depending on the type of work, some workers can rest a week out of every three weeks, and some every two weeks. The company pays for their airfare if they go back home during vacation. Furthermore, due to the high demand from China and the start-up of many large resource projects, competition for labor has increased with many mine workers threatening to switch companies if denied a raise.

Sino Iron and its engineering contractor China Metallurgical Group used to assume that they could transport a large batch of capable (and low-cost) workers from China and rapidly move the project along. However, worker visas became a serious problem. Despite the lobbying of both the companies and the Chinese government, only several hundred visas were issued. Yet, the Australian government required all workers to pass a certification in English, which almost made it impossible for all the workers ready to come.

"If our workers can score a 7 in IELTS (International English Language Testing System), they would not be coming here," Hua Dongyi sighed helplessly. Not only did the Chinese mine workers fail to come, the chefs that CITIC found to cater to the Chinese tastes of their managers could not get visas either. "We have found three chefs successfully, and none of them can get a visa." Now the Chinese managers could only cook for themselves after work in the apartments that they rented.

In order to save labor costs, the project used the world's biggest and most powerful rod mill, the world's largest wheel loader, and the world's largest excavator- with a price tag of US$19 million and a capacity of 1000 tonnes each time. This also promoted the development of China's domestic equipment industry. For example, CITIC Pacific's sister company CITIC Heavy Industries developed a large-scale mining rod mill, which could increase mining abilities by 40% and reduce resource consumption by 20%. Such equipment thus could fully utilize low-grade iron ores and increase the mining efficiency greatly.

Community Relations

"Even though Australia is a developed country, this area is the countryside. In many ways it is not even as good as Africa." This was Hua Dongyi's first impression after arriving at the project site. CITIC Pacific had to invest a great deal in infrastructure. Since the project started in August 2006, billions of dollars have already been invested in the mineral processing plant, pellet plant, slurry pipeline, port facilities, power plant, and desalination plant (see Exhibit 4). One Chinese manager joked, "Usually you would feel more accomplished when you construct things and are able to see the effect. But here it seems that even though you have invested hundreds of thousands of dollars, there is still not much difference." What the Chinese manager did not comment on was that these infrastructure investments could not be taken away, so after the end of the 25-year mining period, they would be given to the locals for free.

Sino Iron also established a team to deal with historical remains, and did a series of explorations on the project site. In 2009, Sino Iron obtained various permits on land development and utilization. With these permits and proper care of historical remains, Sino Iron was able to enter the whole area on the project site, which enabled the smooth operation of construction. The historical remains team also abided by the obligations as listed in the Indigenous Land Use Agreements and ensured the close relationship between the project and the aboriginals living in the area.

Sino Iron also obtained various environmental permits critical to the progress of the project and its future expansion. During the process, the environmental team monitored the underground water, animals in caves, and sea turtles and birds on land. It also audited the environmental performance of its contractor in order to ensure the protection of the natural environment.

By March 2010, Hua had obtained all the key government permits and approvals regarding the environment and historical remains, yet he also began to worry about the cost increases they would bring. A twohole bridge, which would cost about 5 million yuan (about A$800,000) in China, ended up costing over A$50 million since it used steel pipe pile to protect the local environment. The cost differences were incredible. Moreover, many other things drove him crazy. For example, during meetings, usually the first two hours would be spent not discussing issues about the project, but rather environmental protection. For example, if a hole was left in the mining area, would it be necessary to build a ladder in case animals fell into the hole and could not climb up? If they built a two-hole bridge near the dock and there were people working under the bridge, would that disturb the ecological environment of crabs near the seawall?

All of these certainly increased the project's various costs, and were unforeseen before the investment. It appears that when undertaking overseas investments, Chinese managers need to put different priorities on different issues and stakeholders. Things that are easy to deal with in China are often difficult in other countries, and vice versa.

Case Discussion Questions

Who are the stakeholders in the Sino Iron project? How can the Chinese company best engage them?

Explanation

Stakeholders are those people who are co...

Global Business 3rd Edition by Mike Peng

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255