Media Ethics: Issues and Cases 8th Edition by Philip Patterson, Lee Wilkins

Edition 8ISBN: 978-0073526249

Media Ethics: Issues and Cases 8th Edition by Philip Patterson, Lee Wilkins

Edition 8ISBN: 978-0073526249 Exercise 3

Caught in the "War Zone"

MIKE GRUNDMANN AND ROGER SOENKSEN

James Madison University

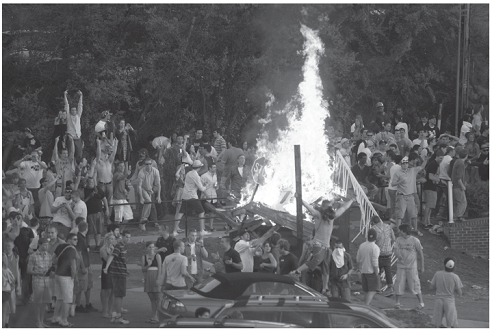

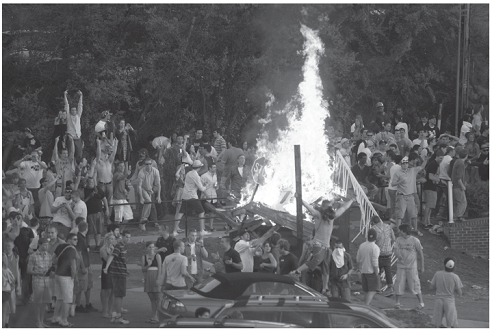

"War Zone" blared the giant headline above photos of fire, vandalism and drunken students being arrested by police in riot gear. This was an out-of-control Springfest, the annual pre-finals block party at James Madison University in Virginia. The Virginia event is but one rite of spring held on college campuses across the nation. Iowa State calls it "Veishea" and that event has turned ugly more than once over the years. At the University of Colorado's similar event, more than 10,000 people show up to smoke pot.

By 2010, on the campus of the University of Virginia, Springfest had ballooned thanks to notices on Facebook that drew students and nonstudents from other states. The 2010 number, estimated to be about 8,000, was about four times larger than previous years according to the Post, and the "block party" began to get out of control. Two photographers for The Breeze, the twice-weekly student newspaper, had taken hundreds of photos of the event and continued as the crowd grew more unruly, spilling into a nearby neighborhood.

According to the Post, President Linwood H. Rose e-mailed the entire 18,500 student campus the following Sunday. "Your collective behavior was an embarrassment to your university and a discredit to our reputation," he wrote. "No one is opposed to some fun on a beautiful spring weekend, but public drunkenness, destruction of property, and threats to personal safety are unacceptable outcomes."

Five days after the melee, the chief local prosecutor, Marsha Garst, was pursuing claims that both attendees and police as well had been assaulted. In trying to find the perpetrators who might have escaped the police dragnet, Garst's office asked The Breeze editor, Katie Thisdell, and a faculty adviser to turn over any unpublished photos so offenders could be identified and arrested. Both refused, on grounds that the paper could not make itself an arm of the law and must remain independent.

The next day, Garst, joined by the campus police chief and other law officers, raided the newsroom with a search warrant. It demanded all Springfest photos under threat of confiscating all computers, cameras, cellphones and other devices that could contain the photos. The number of photos seized in this manner was more than 900, according to the Washington Post.

Acting on the advice of the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), Thisdell refused, citing the federal Privacy Protection Act (PPA), which shields newspapers from such seizures until they can be challenged in court. The PPA was passed in 1980 just after the state of California had successfully pursued a newsroom search and seizure over the objection of the editors. Interestingly, this case, too, also sprang from a college campus-Stanford University, where the students had photos of ariot on campus and had refused to turn them over.

However, this congressional action did not sway Garst, who stuck to her ultimatum. Thisdell, who considered a newsroom emptied of its tools an unacceptable option, relented and turned over all the photos.

Thisdell and her advisers alerted news media in the region, and the story went national, including a Washington Post editorial condemning Garst. The Breeze also provided continuous coverage of its own story, but not using any of the staffers directly involved. The state attorney general, Ken Cuccinelli, at a speaking engagement in town, was asked his opinion of Garst's actions. He supported them.

A lawyer provided free by the SPLC finally convinced Garst of the Privacy Protection Act's provisions and persuaded her to surrender the photos to a neutral third party so negotiations over the next step could begin. The lawyer advised Thisdell: You can stand by your principle and refuse to turn over any of the photos, but with a plurality of conservative judges, there was a risk of a court order essentially matching the search warrant. Or you can negotiate with Garst to turn over the few photos that show suspects Garst is after.

Thisdell, her advisers and her photographers considered the consequences of both choices. Refusing could mean a newsroom shutdown, public accusations of shielding criminals, and weeks, months or years of court appearances. Compromising could embolden future prosecutors, harm The Breeze 's journalistic reputation and discourage important future sources.

Thisdell decided to compromise and ultimately turned over 20 photos. As part of the bargain, The Breeze won a public apology from Garst, who said she regretted frightening the student journalists and would follow the law next time.

Rober Boag, "The Breeze"

Rober Boag, "The Breeze"

How could you counter any claims that the media cooperated in the end to get in good favor with the police?

MIKE GRUNDMANN AND ROGER SOENKSEN

James Madison University

"War Zone" blared the giant headline above photos of fire, vandalism and drunken students being arrested by police in riot gear. This was an out-of-control Springfest, the annual pre-finals block party at James Madison University in Virginia. The Virginia event is but one rite of spring held on college campuses across the nation. Iowa State calls it "Veishea" and that event has turned ugly more than once over the years. At the University of Colorado's similar event, more than 10,000 people show up to smoke pot.

By 2010, on the campus of the University of Virginia, Springfest had ballooned thanks to notices on Facebook that drew students and nonstudents from other states. The 2010 number, estimated to be about 8,000, was about four times larger than previous years according to the Post, and the "block party" began to get out of control. Two photographers for The Breeze, the twice-weekly student newspaper, had taken hundreds of photos of the event and continued as the crowd grew more unruly, spilling into a nearby neighborhood.

According to the Post, President Linwood H. Rose e-mailed the entire 18,500 student campus the following Sunday. "Your collective behavior was an embarrassment to your university and a discredit to our reputation," he wrote. "No one is opposed to some fun on a beautiful spring weekend, but public drunkenness, destruction of property, and threats to personal safety are unacceptable outcomes."

Five days after the melee, the chief local prosecutor, Marsha Garst, was pursuing claims that both attendees and police as well had been assaulted. In trying to find the perpetrators who might have escaped the police dragnet, Garst's office asked The Breeze editor, Katie Thisdell, and a faculty adviser to turn over any unpublished photos so offenders could be identified and arrested. Both refused, on grounds that the paper could not make itself an arm of the law and must remain independent.

The next day, Garst, joined by the campus police chief and other law officers, raided the newsroom with a search warrant. It demanded all Springfest photos under threat of confiscating all computers, cameras, cellphones and other devices that could contain the photos. The number of photos seized in this manner was more than 900, according to the Washington Post.

Acting on the advice of the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), Thisdell refused, citing the federal Privacy Protection Act (PPA), which shields newspapers from such seizures until they can be challenged in court. The PPA was passed in 1980 just after the state of California had successfully pursued a newsroom search and seizure over the objection of the editors. Interestingly, this case, too, also sprang from a college campus-Stanford University, where the students had photos of ariot on campus and had refused to turn them over.

However, this congressional action did not sway Garst, who stuck to her ultimatum. Thisdell, who considered a newsroom emptied of its tools an unacceptable option, relented and turned over all the photos.

Thisdell and her advisers alerted news media in the region, and the story went national, including a Washington Post editorial condemning Garst. The Breeze also provided continuous coverage of its own story, but not using any of the staffers directly involved. The state attorney general, Ken Cuccinelli, at a speaking engagement in town, was asked his opinion of Garst's actions. He supported them.

A lawyer provided free by the SPLC finally convinced Garst of the Privacy Protection Act's provisions and persuaded her to surrender the photos to a neutral third party so negotiations over the next step could begin. The lawyer advised Thisdell: You can stand by your principle and refuse to turn over any of the photos, but with a plurality of conservative judges, there was a risk of a court order essentially matching the search warrant. Or you can negotiate with Garst to turn over the few photos that show suspects Garst is after.

Thisdell, her advisers and her photographers considered the consequences of both choices. Refusing could mean a newsroom shutdown, public accusations of shielding criminals, and weeks, months or years of court appearances. Compromising could embolden future prosecutors, harm The Breeze 's journalistic reputation and discourage important future sources.

Thisdell decided to compromise and ultimately turned over 20 photos. As part of the bargain, The Breeze won a public apology from Garst, who said she regretted frightening the student journalists and would follow the law next time.

Rober Boag, "The Breeze"

Rober Boag, "The Breeze"

How could you counter any claims that the media cooperated in the end to get in good favor with the police?

Explanation

Analyzing the macro issue on photographs...

Media Ethics: Issues and Cases 8th Edition by Philip Patterson, Lee Wilkins

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255