Deck 39: Behavior and the Environment

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/20

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 39: Behavior and the Environment

1

Optimal foraging theory balances costs and benefits of the various methods of finding and hoarding food items, and the danger of being exposed to predators. Discuss the probable differences in foraging behavior of a skunk, a porcupine, and a field mouse.

The skunk is an omnivore and eats plant and animal food. They eat insects of various species. During the warmer months of the year, the larvae of moths and butterflies, beetles and their grubs, grasshoppers and crickets are favourites. Various fruits, berries and seeds such as blueberries and black cherries are included in the summer and autumn diet. Skunk depends on his good sense of vision, hearing, and smell to find food. Skunk depends on their good sense of vision, hearing, and smell to find food. The practice of digging insects from the ground produces tiny conical pits.

Sugar maple trees, basswood, aspen, sapling beech trees, aspen catkins, raspberry stems, shrubs, flowering herbs, oak acorns, beechnuts and a big proportion of apples are included in plants eaten by porcupines. Herbivory affects porcupines' sodium metabolism, leading to a desire for salt. Porcupines mainly feed at night. This is associated with modifications in night plant and leaf chemistry. They use the added nutrients available during the plant's night-time metabolic processes.

Field mice are voracious. They forage mostly at night to avoid predation. They are primarily seed eaters. They also consume tiny invertebrates like snails, insects when there is no seed. While foraging, wood mice collect and distribute visually prominent items, such as leaves and branches, which they use as landmarks during exploration.

Sugar maple trees, basswood, aspen, sapling beech trees, aspen catkins, raspberry stems, shrubs, flowering herbs, oak acorns, beechnuts and a big proportion of apples are included in plants eaten by porcupines. Herbivory affects porcupines' sodium metabolism, leading to a desire for salt. Porcupines mainly feed at night. This is associated with modifications in night plant and leaf chemistry. They use the added nutrients available during the plant's night-time metabolic processes.

Field mice are voracious. They forage mostly at night to avoid predation. They are primarily seed eaters. They also consume tiny invertebrates like snails, insects when there is no seed. While foraging, wood mice collect and distribute visually prominent items, such as leaves and branches, which they use as landmarks during exploration.

2

Do Crabs Eat Sensibly

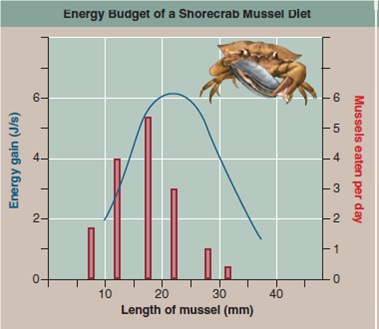

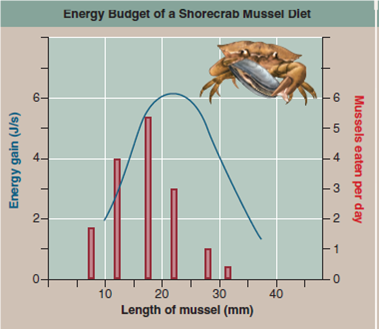

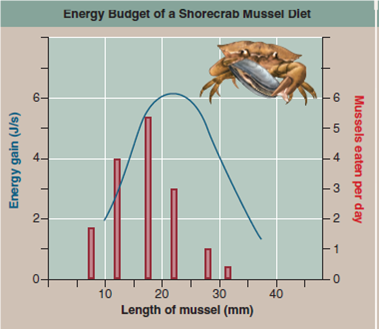

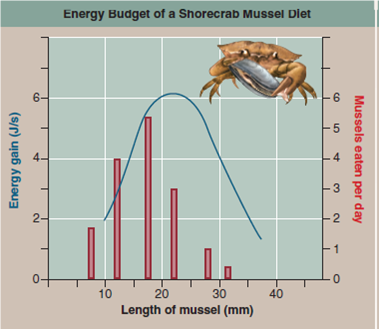

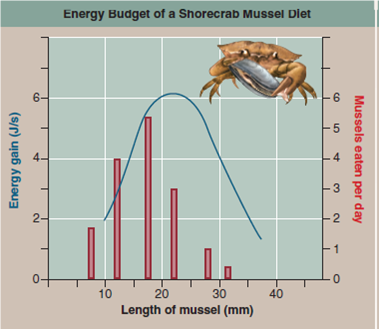

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Drawing Conclusions Do shore crabs tend to feed on those mussels that provide the most energy

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Drawing Conclusions Do shore crabs tend to feed on those mussels that provide the most energy

Shore crabs generally feed on intermediate-sized mussels as it provides maximum energy with minimal loss of energy. The large-sized mussels provide more energy to the crabs but it needs more energy for the crabs to open up the mussels.

Shore crabs generally feed on medium-sized mussels as it provides maximum energy with minimal loss of energy. The most energy can be obtained by feeding on those mussels which are intermediate-sized i.e. size is about 22 mm in length.

Shore crabs generally feed on medium-sized mussels as it provides maximum energy with minimal loss of energy. The most energy can be obtained by feeding on those mussels which are intermediate-sized i.e. size is about 22 mm in length.

3

Training a dog to perform tricks using verbal commands and treats is an example of

A) nonassociative learning.

B) operant conditioning.

C) classical conditioning.

D) imprinting.

A) nonassociative learning.

B) operant conditioning.

C) classical conditioning.

D) imprinting.

Non-associative learning involves learning without linking a stimulus to a response. Repeated stimulus which an animal learns to dismiss is a form of non-associative learning.

Thus, there is no association between the stimulus and the response in non-associative learning. However, the dog has learnt to associate the verbal command and the treat. Hence, option a. is not correct.

We are not considering the dog's response to the verbal command, but are looking at the association it forms between the verbal command and the treat (the dog is not being rewarded/punished for obeying/disobeying the verbal command).

The dog is therefore not associating food with reward. Therefore, this is not a case of operant conditioning. Hence, option b. is also incorrect.

The attachments that an animal forms with other beings or objects as it matures affect its behavior. This is known as imprinting. Thus, young calves stick to their mothers during the period they suckle.

This creates a bond between mother and calf known as filial imprinting. Here, we do not know if the dog has developed an attachment with its trainer.

Hence, option d. is incorrect.

Thus, there is no association between the stimulus and the response in non-associative learning. However, the dog has learnt to associate the verbal command and the treat. Hence, option a. is not correct.

We are not considering the dog's response to the verbal command, but are looking at the association it forms between the verbal command and the treat (the dog is not being rewarded/punished for obeying/disobeying the verbal command).

The dog is therefore not associating food with reward. Therefore, this is not a case of operant conditioning. Hence, option b. is also incorrect.

The attachments that an animal forms with other beings or objects as it matures affect its behavior. This is known as imprinting. Thus, young calves stick to their mothers during the period they suckle.

This creates a bond between mother and calf known as filial imprinting. Here, we do not know if the dog has developed an attachment with its trainer.

Hence, option d. is incorrect.

4

What are some of the reasons advanced for altruism among groups of animals Give some examples.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

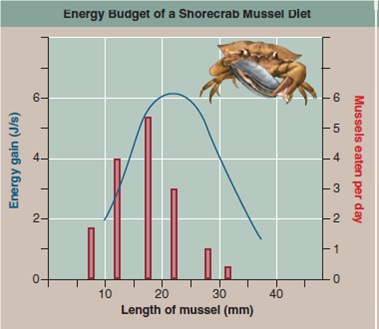

Do Crabs Eat Sensibly

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Further Analysis What factors might be responsible for the slight difference in peak prey length relative to the length optimal for maximal energy gain

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Further Analysis What factors might be responsible for the slight difference in peak prey length relative to the length optimal for maximal energy gain

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

Behavior can be tied to ecology and evolution by considering what the behavior does to increase

a. body size.

b. number of breeding sites.

c. reproductive fitness.

d. territory size.

a. body size.

b. number of breeding sites.

c. reproductive fitness.

d. territory size.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

The selection of foods and the journey to seek those foods is called

A) territoriality.

B) optimal foraging theory.

C) migratory behavior.

D) foraging behavior.

A) territoriality.

B) optimal foraging theory.

C) migratory behavior.

D) foraging behavior.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Courtship rituals are thought to have come about through

A) intrasexual selection.

B) agonistic behavior.

C) intersexual selection.

D) kin selection.

A) intrasexual selection.

B) agonistic behavior.

C) intersexual selection.

D) kin selection.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

"Nature versus nurture" is an old argument regarding which factor predominates in behavior. How have studies of hybrids and of human twins helped us learn more

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

A mating system where the female mates with more than one male is

A) protandry.

B) polyandry.

C) polygyny.

D) monogamy.

A) protandry.

B) polyandry.

C) polygyny.

D) monogamy.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

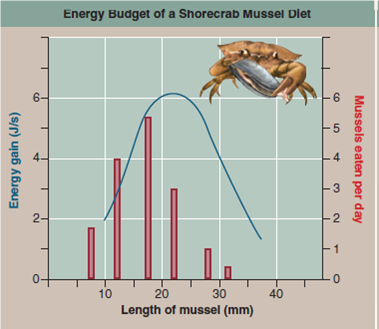

Do Crabs Eat Sensibly

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Applying Concepts What is the dependent variable in the curve in the histogram

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Applying Concepts What is the dependent variable in the curve in the histogram

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

Sharing of blood meals between fed and hungry vampire bats and the shunning of a bat who takes but doesn't share are examples of

a. helpers.

b. kin selection.

c. reciprocity.

d. group selection.

a. helpers.

b. kin selection.

c. reciprocity.

d. group selection.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Innate behavior patterns

A) can be modified if the stimulus changes.

B) cannot be modified, as these behaviors seem built into the brain and nervous system.

C) can be modified if environmental conditions begin to vary over a long period, a year or more.

D) cannot be modified, as these behaviors are learned while very young.

A) can be modified if the stimulus changes.

B) cannot be modified, as these behaviors seem built into the brain and nervous system.

C) can be modified if environmental conditions begin to vary over a long period, a year or more.

D) cannot be modified, as these behaviors are learned while very young.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

Bird offspring who help their parents care for younger offspring are showing

a. brood parasitism.

b. kin selection.

c. reciprocity.

d. group selection.

a. brood parasitism.

b. kin selection.

c. reciprocity.

d. group selection.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

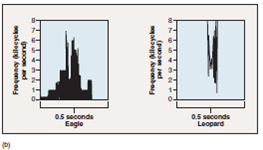

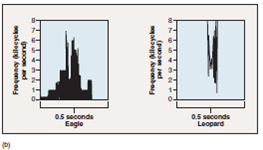

Figure 39.2 b What does the experiment illustrated here reveal about certain types of fixed or innate behaviors

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

While vertebrate animal societies are more loosely structured than insect societies, the organization of these societies is most influenced by

A) which females are receptive to reproduction.

B) migration patterns.

C) how large the territory is compared to neighboring societies.

D) ecological factors such as food type and predation.

A) which females are receptive to reproduction.

B) migration patterns.

C) how large the territory is compared to neighboring societies.

D) ecological factors such as food type and predation.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

Some behaviors require both genetic (nature) and environmental (nurture) input to be carried out. Explain how these two forces interact to affect the song of the white-crowned sparrow.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

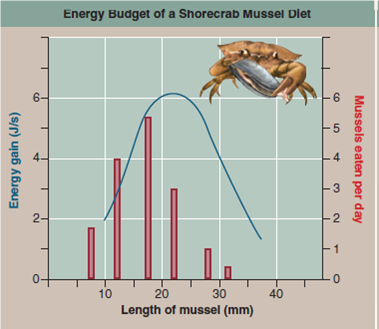

Do Crabs Eat Sensibly

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Making Inferences

a. What is the most energetically optimal mussel size for the crabs to eat, in mm

b. What size mussel is most frequently eaten by crabs, in mm

Many behavioral ecologists claim that animals exhibit so-called optimal foraging behavior. The idea is that because an animal's choice in seeking food involves a trade-offbetween the food's energy content and the cost of obtaining it, evolution should favor foraging behaviors that optimize the trade-off.

While this all makes sense, it is not at all clear that this is what animals would actually do. This optimal foraging approach makes a key assumption, that maximizing the amount of energy acquired will lead to increased reproductive success. In some cases this is clearly true. As discussed earlier in this chapter, in ground squirrels, zebra finches, and orb-weaving spiders, researchers have found a direct relationship between net energy intake and the number of offspring raised successfully.

However, animals have other needs besides energy, and sometimes these needs conflict. One obvious "other need," important to many animals, is to avoid predators. It makes little sense for you to eat a little more food if doing so greatly increases the probability that you will yourself be eaten. Often the behavior that maximizes energy intake increases predation risk. A shore crab foraging for mussels on a beach exposes itself to predatory gulls and other shore birds with each foray. Thus the behavior that maximizes fitness may reflect a trade-off, obtaining the most energy with the least risk of being eaten. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of animals use a more cautious foraging behavior when predators are present-becoming less active and staying nearer to cover.

So what does a shore crab do To find out, an investigator looked to see if shore crabs in fact feed on those mussels which provide the most energy, as the theory predicts. He found that the mussels on the beach he studied come in a range of sizes, from small ones less than 10 mm in length that are easy for a crab to open but yield the least amount of energy, to large mussels over 30 mm in length that yield the most energy but also take considerably more energy to pry open. To obtain the most net energy, the optimal approach, described by the blue curve in the graph above, would be for shore crabs to feed primarily on intermediate-sized mussels about 22 mm in length. Is this in fact what shore crabs do To find out, the researcher carefully monitored the size of the mussels eaten each day by the beach's population of shore crabs. The results he obtained-the numbers of mussels of each size actually eaten-are presented in the red histogram above.

Making Inferences

a. What is the most energetically optimal mussel size for the crabs to eat, in mm

b. What size mussel is most frequently eaten by crabs, in mm

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

The study of mouse maternal behavior shows a clearer genetic effect on behavior than lovebird or human twin studies because

A) there is a clear link between presence or absence of a specifi c gene, a specifi c metabolic pathway, and a specifi c behavior.

B) the behavior of mice was less complex and easier to study than lovebirds or human twins.

C) parental care has a larger infl uence on mice than on lovebirds and humans.

D) No answer is correct.

A) there is a clear link between presence or absence of a specifi c gene, a specifi c metabolic pathway, and a specifi c behavior.

B) the behavior of mice was less complex and easier to study than lovebirds or human twins.

C) parental care has a larger infl uence on mice than on lovebirds and humans.

D) No answer is correct.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

20

Figure 39.14 b What does this graph imply about communication in nonhuman primates

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 20 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck