Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022 Exercise 25

The unlikely 2002 trip to Africa by the Irish rock star Bono in the company of U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill sparked much interesting dialogue about economics.1 Especially intriguing was Bono's claim that recently expanded agricultural subsidies in the United States were harming struggling farmers in Africa-a charge that O'Neill was forced to attempt to refute at every stop. A simple supply-demand analysis shows that, overall, Bono did indeed have the better of the arguments, though he neglected to mention a few fine points.

Graphing African Exports

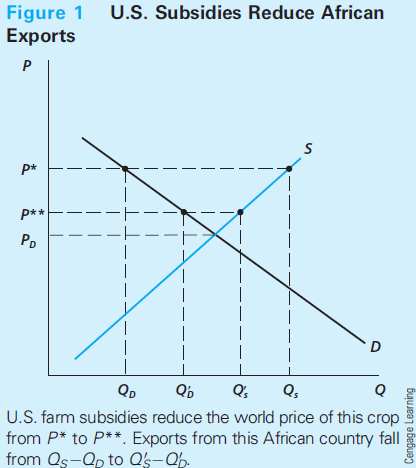

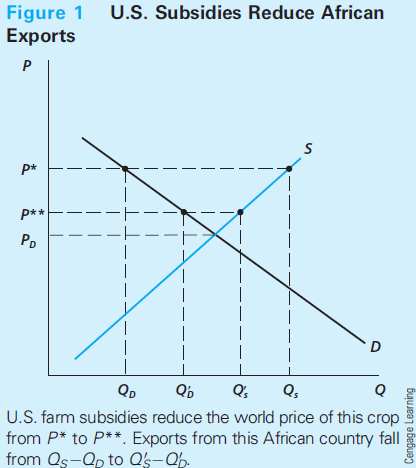

Figure 1 shows the supply and demand curves for a typical crop that is being produced by an African country. If the world price of this crop (P*) exceeds the price that would prevail in the absence of trade (PD), this country will be an exporter of this crop. The total quantity of exports is given by the distance QS -QD. That is, exports are given by the difference in the quantity of this crop produced and the quantity that is demanded domestically. Such exporting is common for many African countries because they have large agrarian populations and generally favorable climates for many types of food production.

In May 2002, the United States adopted a program of vastly increased agricultural subsidies to U.S. farmers. From the point of view of world markets, the main effect of such a program was to reduce world crop prices. This is shown in Figure 1 as a drop in the world price to P **. This fall in price would be met by a reduction in quantity produced of the crop to . Crop exports would decline significantly.

. Crop exports would decline significantly.

So, Bono's point is essentially correct-U.S. farm subsidies do harm African farmers, especially those in the export business. But he might also have pointed out that African consumers of food also benefit from the price reduction.

They are able to buy more food at lower prices. Effectively, some of the subsidy to U.S. farmers has been transferred to African consumers. Hence, even disregarding whether farm subsidies make any sense for Americans, their effects on the welfare of Africans is ambiguous.

Other Barriers to African Agricultural Trade

Agricultural subsidies by the United States and the European Union amount to over $500 billion per year. Undoubtedly, they

have a major effect in thwarting African exports. Perhaps even more devastating are the large number of special measures adopted in various developed countries to protect favored domestic industries such as peanuts in the United States, rice in Japan, and livestock and bananas in the European Union. Because expanded trade is one of the major avenues through which poor African economies might grow, these restrictions deserve serious scrutiny.

Why do the United States and European countries subsidize farm output? What goals do these countries seek to achieve by such programs (possibly lower food prices or higher incomes for farmers)? Is the subsidization of crop prices the best way to achieve these goals?

Graphing African Exports

Figure 1 shows the supply and demand curves for a typical crop that is being produced by an African country. If the world price of this crop (P*) exceeds the price that would prevail in the absence of trade (PD), this country will be an exporter of this crop. The total quantity of exports is given by the distance QS -QD. That is, exports are given by the difference in the quantity of this crop produced and the quantity that is demanded domestically. Such exporting is common for many African countries because they have large agrarian populations and generally favorable climates for many types of food production.

In May 2002, the United States adopted a program of vastly increased agricultural subsidies to U.S. farmers. From the point of view of world markets, the main effect of such a program was to reduce world crop prices. This is shown in Figure 1 as a drop in the world price to P **. This fall in price would be met by a reduction in quantity produced of the crop to

. Crop exports would decline significantly.

. Crop exports would decline significantly.So, Bono's point is essentially correct-U.S. farm subsidies do harm African farmers, especially those in the export business. But he might also have pointed out that African consumers of food also benefit from the price reduction.

They are able to buy more food at lower prices. Effectively, some of the subsidy to U.S. farmers has been transferred to African consumers. Hence, even disregarding whether farm subsidies make any sense for Americans, their effects on the welfare of Africans is ambiguous.

Other Barriers to African Agricultural Trade

Agricultural subsidies by the United States and the European Union amount to over $500 billion per year. Undoubtedly, they

have a major effect in thwarting African exports. Perhaps even more devastating are the large number of special measures adopted in various developed countries to protect favored domestic industries such as peanuts in the United States, rice in Japan, and livestock and bananas in the European Union. Because expanded trade is one of the major avenues through which poor African economies might grow, these restrictions deserve serious scrutiny.

Why do the United States and European countries subsidize farm output? What goals do these countries seek to achieve by such programs (possibly lower food prices or higher incomes for farmers)? Is the subsidization of crop prices the best way to achieve these goals?

Explanation

Many developed nations like United State...

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255