Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022 Exercise 27

Zero-Coupon Bonds

U.S. Treasury notes pay their interest semiannually. In the past, each bond had a series of coupons for these interest payments. An owner would clip off a payment coupon and turn it in to the Treasury for payment. This is the origin of the term "coupon clipper" for elderly Scrooge-type characters living off their bond holdings. Today, of course, coupons are a thing of the past. Bond owners are recorded on computer files, and checks are routinely sent out to them when interest payments are due. Still, the idea that bonds are nothing more than a big coupon book of interest payments to be made at specific dates has spawned a variety of innovations.

Invention of Zero-Coupon Bonds

One of the most important such innovations occurred in the late 1970s when large financial institutions started buying large numbers of Treasury bonds and "stripping" off the interest (and principal) payments into separate financial assets. For example, consider a 10-year treasury note that promises 20 semiannual interest payments of $20 on each $1,000 bond together with a return of the $1,000 principal in 10 years. A large financial institution can buy $100 million of such bonds and sell off $2 million worth of interest payments for each of the 20 semiannual interest payment dates into the future. The firm can also sell $100 million of principal payments due in 10 years. Hence it has created 21 new financial assets based on its underlying bond holdings. Because the payments promised by these assets are supported by actual bond holdings of the financial institution, they are a low-risk investment for people who will need their funds at specific dates in the future.

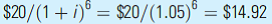

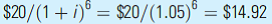

Applying the PDV Formula Because the interest and principal payments will not be received until some date in the future, we must use present-value calculations to determine what they are worth today. For example, a promised interest payment of $20 in, say, six years with an interest rate of 5 percent would be worth today. A buyer that paid $14.92 for the promise of $20 in six years would achieve a return of 5 percent on his or her funds and would avoid the hassle of having to deal with periodic interest payments.

today. A buyer that paid $14.92 for the promise of $20 in six years would achieve a return of 5 percent on his or her funds and would avoid the hassle of having to deal with periodic interest payments.

Yields on Zeros

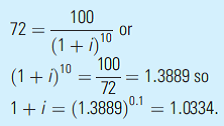

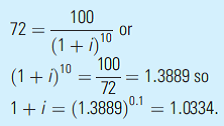

Zero-coupon bonds trade regularly in the open market. The price of this promise to pay a set amount in the future is determined by the forces of supply and demand, just like any other good. Using this market price it is then possible to calculate the implicit yield (that is the effective interest rate) being promised by using the present value-formula. For example, in late 2013, a 10-year "strip" that promised to pay $100 in 10 years was priced at about $72. The yield on this investment can be calculated by solving the following equation for i :

So, the implicit rate of interest being promised on this zero coupon bond is about 3.34 percent. 1 A person who buys the zero at $72 will receive the equivalent of an interest rate of 3.34 percent on his or her investment after 10 years.

Does an investor who buys a zero-coupon bond have to hold onto the asset until it comes due? Suppose that a person who bought the 10-year strip described above decided to sell it after four years. What would determine the yield he or she actually received on the investment? What would determine the yield this seller could get if he or she wanted to invest the proceeds for a new 10-year period?

U.S. Treasury notes pay their interest semiannually. In the past, each bond had a series of coupons for these interest payments. An owner would clip off a payment coupon and turn it in to the Treasury for payment. This is the origin of the term "coupon clipper" for elderly Scrooge-type characters living off their bond holdings. Today, of course, coupons are a thing of the past. Bond owners are recorded on computer files, and checks are routinely sent out to them when interest payments are due. Still, the idea that bonds are nothing more than a big coupon book of interest payments to be made at specific dates has spawned a variety of innovations.

Invention of Zero-Coupon Bonds

One of the most important such innovations occurred in the late 1970s when large financial institutions started buying large numbers of Treasury bonds and "stripping" off the interest (and principal) payments into separate financial assets. For example, consider a 10-year treasury note that promises 20 semiannual interest payments of $20 on each $1,000 bond together with a return of the $1,000 principal in 10 years. A large financial institution can buy $100 million of such bonds and sell off $2 million worth of interest payments for each of the 20 semiannual interest payment dates into the future. The firm can also sell $100 million of principal payments due in 10 years. Hence it has created 21 new financial assets based on its underlying bond holdings. Because the payments promised by these assets are supported by actual bond holdings of the financial institution, they are a low-risk investment for people who will need their funds at specific dates in the future.

Applying the PDV Formula Because the interest and principal payments will not be received until some date in the future, we must use present-value calculations to determine what they are worth today. For example, a promised interest payment of $20 in, say, six years with an interest rate of 5 percent would be worth

today. A buyer that paid $14.92 for the promise of $20 in six years would achieve a return of 5 percent on his or her funds and would avoid the hassle of having to deal with periodic interest payments.

today. A buyer that paid $14.92 for the promise of $20 in six years would achieve a return of 5 percent on his or her funds and would avoid the hassle of having to deal with periodic interest payments.Yields on Zeros

Zero-coupon bonds trade regularly in the open market. The price of this promise to pay a set amount in the future is determined by the forces of supply and demand, just like any other good. Using this market price it is then possible to calculate the implicit yield (that is the effective interest rate) being promised by using the present value-formula. For example, in late 2013, a 10-year "strip" that promised to pay $100 in 10 years was priced at about $72. The yield on this investment can be calculated by solving the following equation for i :

So, the implicit rate of interest being promised on this zero coupon bond is about 3.34 percent. 1 A person who buys the zero at $72 will receive the equivalent of an interest rate of 3.34 percent on his or her investment after 10 years.

Does an investor who buys a zero-coupon bond have to hold onto the asset until it comes due? Suppose that a person who bought the 10-year strip described above decided to sell it after four years. What would determine the yield he or she actually received on the investment? What would determine the yield this seller could get if he or she wanted to invest the proceeds for a new 10-year period?

Explanation

The payment structure on zero-coupon bon...

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255