Deck 11: Section 3: Development

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/14

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 11: Section 3: Development

1

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The results obtained in the experimental condition by Gopnik and Astington (1988) suggests that three-year-olds treat their past selves as:

A)reference points for evaluating changes in mental representations.

B)if they were other people.

C)unreliable sources of information.

D)authority figures whose decisions are final.

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The results obtained in the experimental condition by Gopnik and Astington (1988) suggests that three-year-olds treat their past selves as:

A)reference points for evaluating changes in mental representations.

B)if they were other people.

C)unreliable sources of information.

D)authority figures whose decisions are final.

if they were other people.

2

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

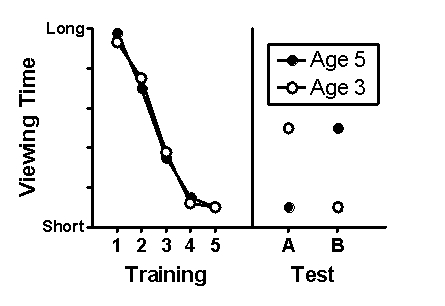

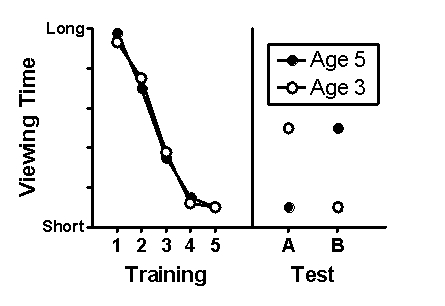

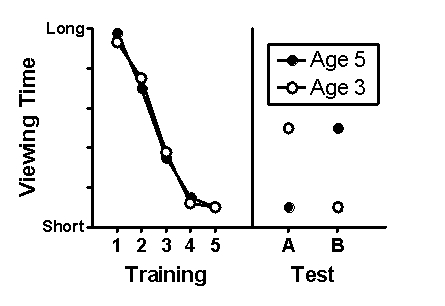

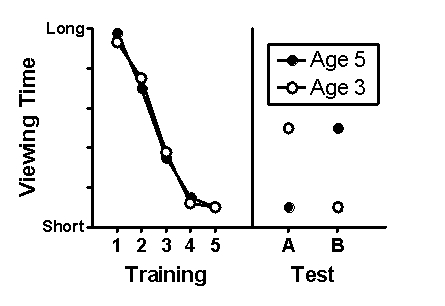

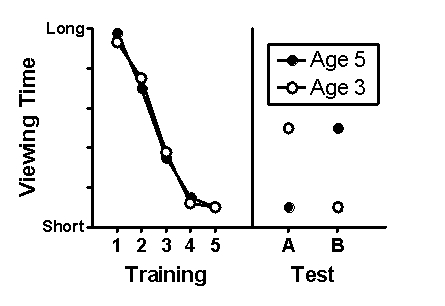

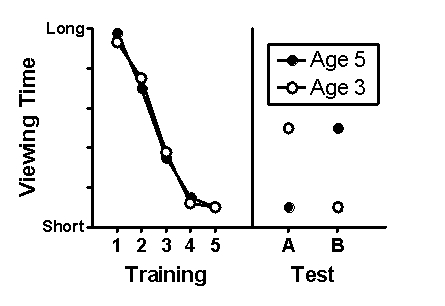

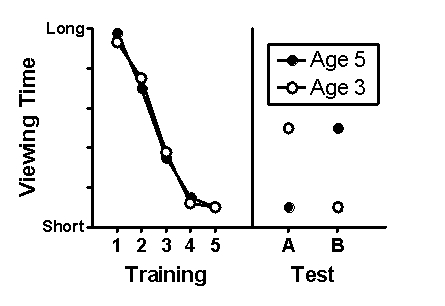

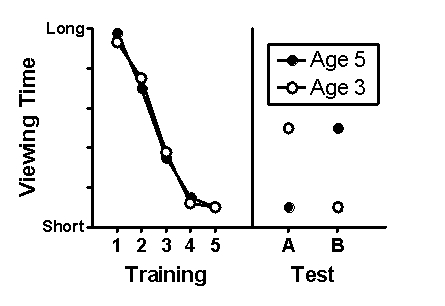

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Based on the data shown in Figure 11.1, which group(s) of infants, if any, appear to possess a concept of gravity?

A)three-month-olds

B)five-month-olds

C)both groups, although they have different expectancies about gravitational effects

D)neither group

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Based on the data shown in Figure 11.1, which group(s) of infants, if any, appear to possess a concept of gravity?

A)three-month-olds

B)five-month-olds

C)both groups, although they have different expectancies about gravitational effects

D)neither group

five-month-olds

3

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) Lacking a theory of mind, three-year-olds in Wimmer and Perner's (1983) study demonstrated:

A)egocentrism.

B)an illusory conjunction.

C)the conjunction fallacy.

D)concrete operations.

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) Lacking a theory of mind, three-year-olds in Wimmer and Perner's (1983) study demonstrated:

A)egocentrism.

B)an illusory conjunction.

C)the conjunction fallacy.

D)concrete operations.

egocentrism.

4

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) In order to respond correctly in Wimmer and Perner's (1983) study, children need to:

A)demonstrate a relativistic moral development.

B)demonstrate formal operations of logic.

C)understand that other people's mental representations guide their behavior.

D)consult their own mental representation of the ball location.

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) In order to respond correctly in Wimmer and Perner's (1983) study, children need to:

A)demonstrate a relativistic moral development.

B)demonstrate formal operations of logic.

C)understand that other people's mental representations guide their behavior.

D)consult their own mental representation of the ball location.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The fact that three-year olds in the Gopnik and Astington (1988) study responded accurately in the control condition but inaccurately in the experimental condition:

A)results in only partial support for Wimmer and Perner's (1983) original findings.

B)demonstrates that minor procedural details can affect whether children demonstrate a theory of mind.

C)illustrates the distinction between beliefs about the world and beliefs about beliefs.

D)illustrates the distinction between concrete and formal operations.

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The fact that three-year olds in the Gopnik and Astington (1988) study responded accurately in the control condition but inaccurately in the experimental condition:

A)results in only partial support for Wimmer and Perner's (1983) original findings.

B)demonstrates that minor procedural details can affect whether children demonstrate a theory of mind.

C)illustrates the distinction between beliefs about the world and beliefs about beliefs.

D)illustrates the distinction between concrete and formal operations.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

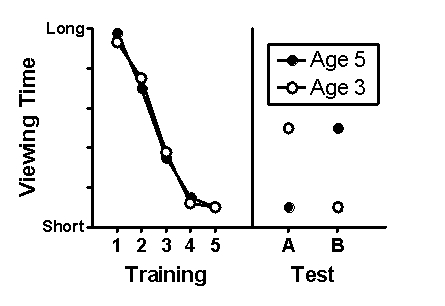

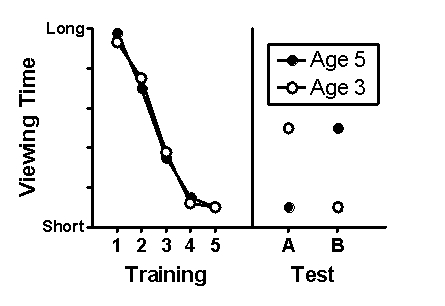

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) This study exploits the well-known finding that infants generally will _____objects or scenarios that are _____.

A)stare longer at; familiar

B)stare longer at; surprising

C)divert gaze from; novel

D)divert gaze from; physically impossible

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) This study exploits the well-known finding that infants generally will _____objects or scenarios that are _____.

A)stare longer at; familiar

B)stare longer at; surprising

C)divert gaze from; novel

D)divert gaze from; physically impossible

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

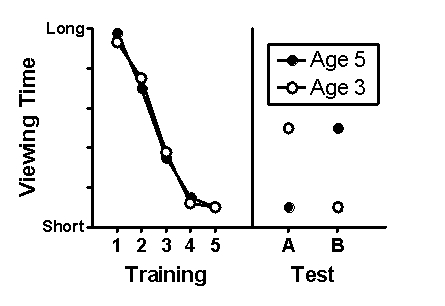

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which is the likely explanation for the decreased looking time across training trials?

A)Both groups of infants failed to acquire gravitational expectancies.

B)The video lost its novelty.

C)Both groups of infants acquired object permanence with respect to the ball.

D)The experimenters failed to arrange effective rewards for looking behavior.

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which is the likely explanation for the decreased looking time across training trials?

A)Both groups of infants failed to acquire gravitational expectancies.

B)The video lost its novelty.

C)Both groups of infants acquired object permanence with respect to the ball.

D)The experimenters failed to arrange effective rewards for looking behavior.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

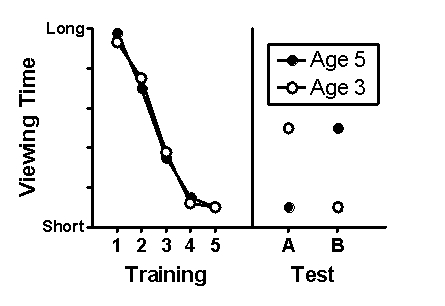

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which statement pertaining to the test trials is true?

A)Test trials A have greater stimulus novelty than test trials B.

B)Test trials A depict a scenario that is inconsistent with gravitational effects.

C)Both trial types depict a scenario that is inconsistent with gravitational effects.

D)Test trials B have greater stimulus novelty than test trials A.

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which statement pertaining to the test trials is true?

A)Test trials A have greater stimulus novelty than test trials B.

B)Test trials A depict a scenario that is inconsistent with gravitational effects.

C)Both trial types depict a scenario that is inconsistent with gravitational effects.

D)Test trials B have greater stimulus novelty than test trials A.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) Wimmer and Perner's (1983) procedure is commonly referred to as a _____ test.

A)object permanence

B)false-belief

C)conservation

D)change blindness

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) Wimmer and Perner's (1983) procedure is commonly referred to as a _____ test.

A)object permanence

B)false-belief

C)conservation

D)change blindness

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

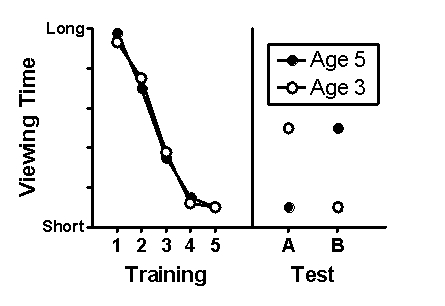

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which is a true inference based on the data shown in Figure 11.1?

A)Three-month-olds were more easily surprised by the test trials than five-month olds.

B)Throughout the experiment, five-month-olds exhibited greater attention spans than three-month-olds.

C)Test trials revealed that five-month-olds, but not three-month-olds, developed object permanence to the ball.

D)Three-month-olds were more attracted to the novel features of the test stimuli than five-months-olds.

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Which is a true inference based on the data shown in Figure 11.1?

A)Three-month-olds were more easily surprised by the test trials than five-month olds.

B)Throughout the experiment, five-month-olds exhibited greater attention spans than three-month-olds.

C)Test trials revealed that five-month-olds, but not three-month-olds, developed object permanence to the ball.

D)Three-month-olds were more attracted to the novel features of the test stimuli than five-months-olds.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

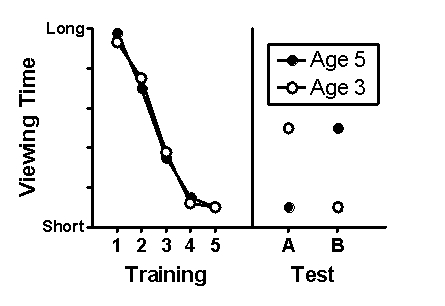

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Kim and Spelke (1992) utilized a simple form of learning termed _____ to investigate their research question.

A)extinction.

B)object permanence.

C)the false-belief test.

D)habituation.

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Kim and Spelke (1992) utilized a simple form of learning termed _____ to investigate their research question.

A)extinction.

B)object permanence.

C)the false-belief test.

D)habituation.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) In the Gopnik and Astington (1988) study, the control question "What used to be in the dollhouse?" is analogous to asking children in the Wimmer and Perner (1983) study:

A)Where does Maxi expect to find the chocolate?

B)Where do you think the chocolate is?

C)Where does the second puppet think the chocolate is?

D)Where did Maxi hide the chocolate?

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) In the Gopnik and Astington (1988) study, the control question "What used to be in the dollhouse?" is analogous to asking children in the Wimmer and Perner (1983) study:

A)Where does Maxi expect to find the chocolate?

B)Where do you think the chocolate is?

C)Where does the second puppet think the chocolate is?

D)Where did Maxi hide the chocolate?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The control condition conducted by Gopnik and Astington (1988) helps eliminate all of these explanations of the general findings by Wimmer and Perner (1983) EXCEPT:

A)Three-year-olds make decisions based on their own mental representations.

B)Three-year olds are biased to answer questions with recent knowledge.

C)Three-year-olds have problems sequencing events in time.

D)Three-year-olds lack the attention span necessary to remember critical details of the story.

Scenario II is based on the following studies:

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children's understanding of representative change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26-37.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition, 13(1), 103-128.

Wimmer and Perner (1983) first developed a procedure to assess if children have developed a theory of mind. Children were read an illustrated story in which a puppet named Maxi hid a piece of chocolate in one cupboard and then left the room. While Maxi was away, a second puppet entered the room, discovered the chocolate, and hid it in a new location before leaving. The story ended with Maxi's return. Children were asked where Maxi will look for the chocolate. Whereas most five-year-olds who have developed a theory of mind will report that he will look in the cupboard, most three-year-olds will report that Maxi will look in the new location.

Using a different procedure, Gopnik and Astington (1988) first arranged a control condition in which children were shown a dollhouse. Inside the dollhouse was an apple. In the presence of the children, the experimenter opened the dollhouse and replaced the apple with a doll. A few minutes later, the children were asked what was currently in the dollhouse and what had previously been in the dollhouse. Only children who answered these questions correctly progressed to the experimental condition. Here, the experimenter showed children a candy box. When they opened it, the children discovered that it contained pencils. When the children were asked what they originally thought was in the box, most five-year-olds said candy and most three-year-olds said pencils.

(Scenario II) The control condition conducted by Gopnik and Astington (1988) helps eliminate all of these explanations of the general findings by Wimmer and Perner (1983) EXCEPT:

A)Three-year-olds make decisions based on their own mental representations.

B)Three-year olds are biased to answer questions with recent knowledge.

C)Three-year-olds have problems sequencing events in time.

D)Three-year-olds lack the attention span necessary to remember critical details of the story.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Evidence of the presence or absence of gravitational expectancies were operationally defined in terms of:

A)the age of the infants.

B)the type of test trials.

C)differential looking times at the two test videos.

D)the number of training trials required for infants to lose interest in the video.

Scenario I is based on and presents fabricated results consistent with the following study:

Kim, I. K., & Spelke, E. S. (1992). Infants' sensitivity to effects of gravity on visual object motion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 385-393.

Kim and Spelke (1992) investigated the extent to which infants have expectancies of gravitational effects on visual object motion. Three- and five-month-old infants repeatedly watched a video of a ball accelerating as it rolled down an incline until they spent little time actively looking at it. Subsequently, two types of test trials were conducted in randomized order. Type A test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled up an incline. Type B test trials consisted of a ball slowing down as it rolled down an incline. During all trials, the amount of time looking at each visual display was recorded. Fabricated data consistent with the major finding of this study are presented in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1

(Scenario I) Evidence of the presence or absence of gravitational expectancies were operationally defined in terms of:

A)the age of the infants.

B)the type of test trials.

C)differential looking times at the two test videos.

D)the number of training trials required for infants to lose interest in the video.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 14 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck