Deck 9: Section 3: Language and Thought

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/13

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 9: Section 3: Language and Thought

1

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

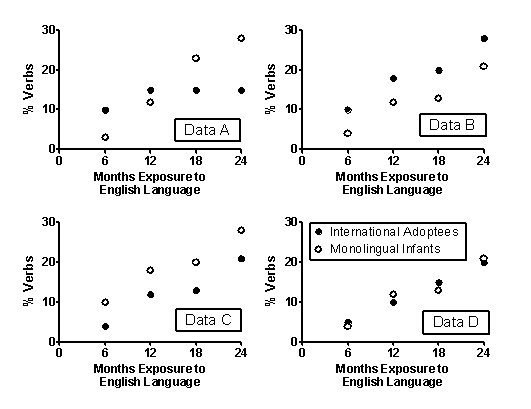

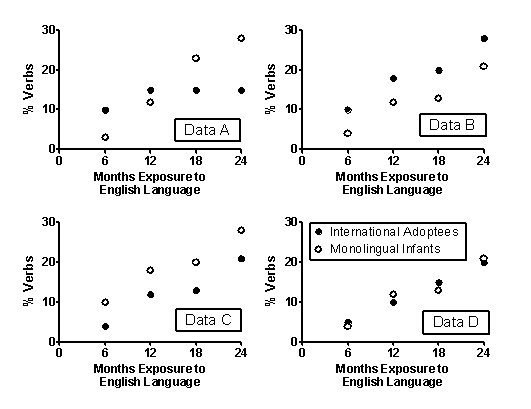

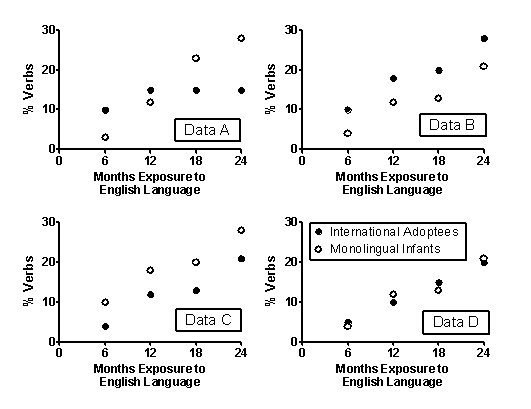

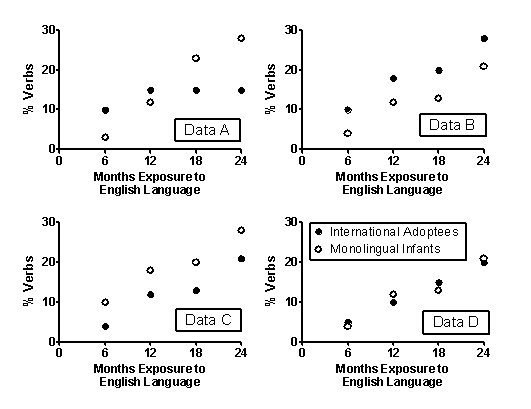

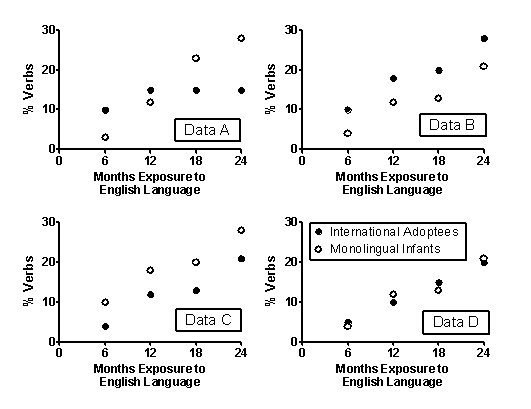

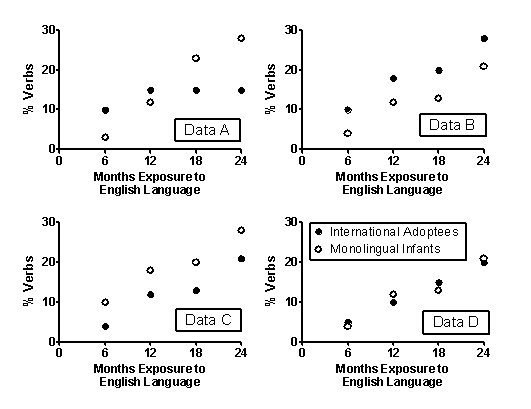

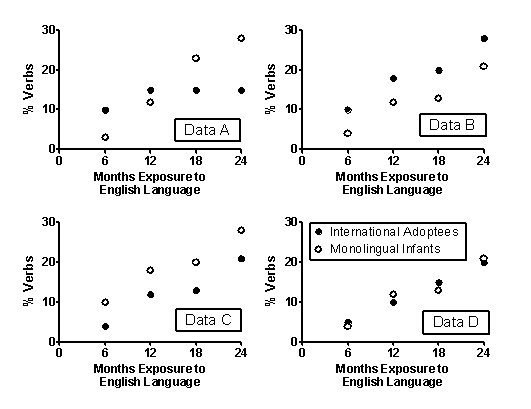

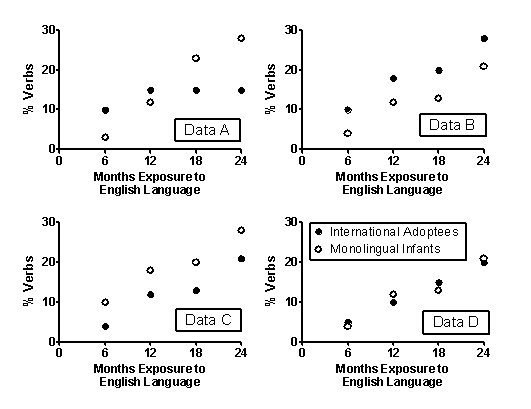

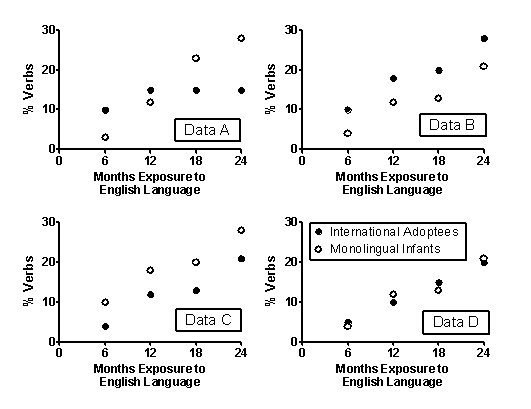

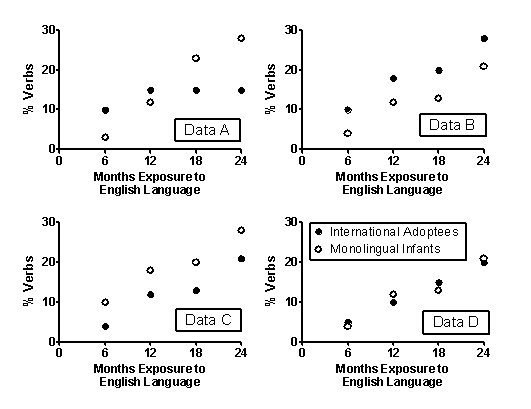

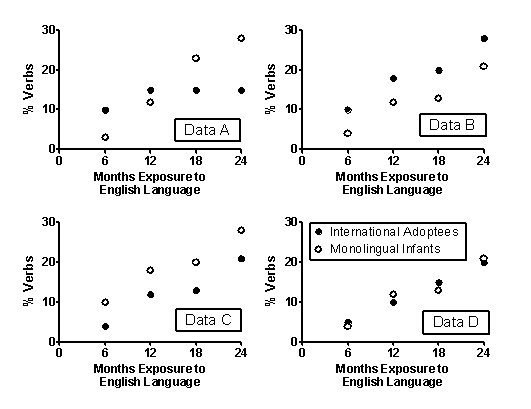

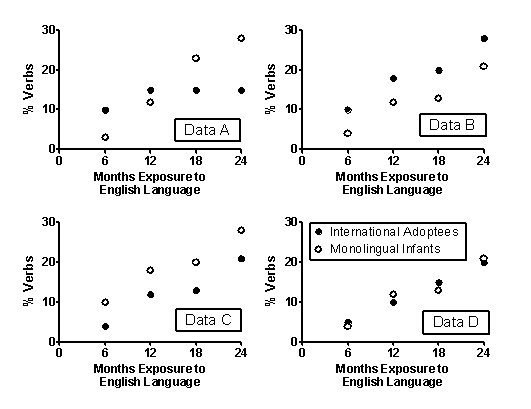

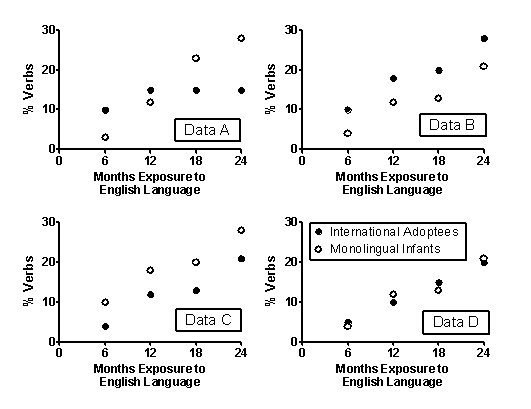

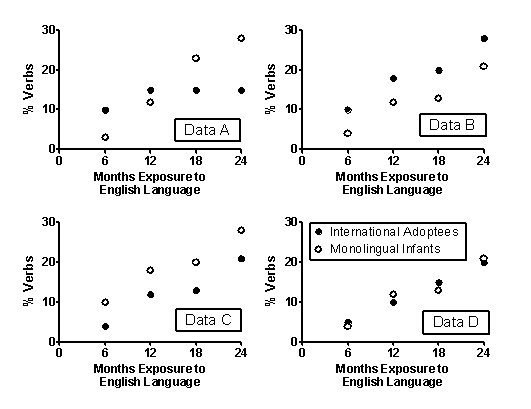

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Snedeker et al. (2007) refers to their research program as a "natural experiment." However, for which reason is it NOT an example of a true experimental design?

A)Participants were not sampled randomly from the population.

B)The study is not empirical in nature and lacks measurement reliability.

C)There is no random assignment to groups and no manipulation of an independent variable.

D)It is difficult to ascertain if the results would generalize to other languages.

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Snedeker et al. (2007) refers to their research program as a "natural experiment." However, for which reason is it NOT an example of a true experimental design?

A)Participants were not sampled randomly from the population.

B)The study is not empirical in nature and lacks measurement reliability.

C)There is no random assignment to groups and no manipulation of an independent variable.

D)It is difficult to ascertain if the results would generalize to other languages.

There is no random assignment to groups and no manipulation of an independent variable.

2

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) In a second study, Snedeker et al. (2012) found that older (e.g., 5 year-old) internationally adopted children acquiring English as a second language began correctly using words pertaining to time (e.g., yesterday, tomorrow) earlier in their exposure to English than monolingual infant controls. This observed difference is best interpreted as:

A)support for the contention that linguistic development is a separate process from cognitive development.

B)resulting from a more advanced cognitive development in the older children.

C)a reflection of previously developed linguistic expertise in the older children's first language.

D)resulting from some combination of more advanced cognitive development and previous linguistic development in the older children's first language.

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) In a second study, Snedeker et al. (2012) found that older (e.g., 5 year-old) internationally adopted children acquiring English as a second language began correctly using words pertaining to time (e.g., yesterday, tomorrow) earlier in their exposure to English than monolingual infant controls. This observed difference is best interpreted as:

A)support for the contention that linguistic development is a separate process from cognitive development.

B)resulting from a more advanced cognitive development in the older children.

C)a reflection of previously developed linguistic expertise in the older children's first language.

D)resulting from some combination of more advanced cognitive development and previous linguistic development in the older children's first language.

resulting from some combination of more advanced cognitive development and previous linguistic development in the older children's first language.

3

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which data set in Figure 9.1 provides the most support for the contention that language development is critically dependent on experience with the language?

A)data set A

B)data set B

C)data set C

D)data set D

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which data set in Figure 9.1 provides the most support for the contention that language development is critically dependent on experience with the language?

A)data set A

B)data set B

C)data set C

D)data set D

data set D

4

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment illustrate the role of emotional experience on decision making. Choice situations involving probabilistic outcomes often elicit feelings of anxiety, operationally defined in this study as:

A)the anticipatory GSR.

B)the post-outcome GSR.

C)deck preference.

D)the programmed rate of wins and losses among decks.

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment illustrate the role of emotional experience on decision making. Choice situations involving probabilistic outcomes often elicit feelings of anxiety, operationally defined in this study as:

A)the anticipatory GSR.

B)the post-outcome GSR.

C)deck preference.

D)the programmed rate of wins and losses among decks.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment suggest that individuals with this particular brain damage exhibit the greatest deficits in the ability to:

A)experience emotions related to wins and losses.

B)modify behavior based on future consequences.

C)calculate odds ratios.

D)identify the difference between a risky and safe choice.

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment suggest that individuals with this particular brain damage exhibit the greatest deficits in the ability to:

A)experience emotions related to wins and losses.

B)modify behavior based on future consequences.

C)calculate odds ratios.

D)identify the difference between a risky and safe choice.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment suggest that the ability to correctly identify optimal game strategy is:

A)not necessary to choose optimally.

B)required to choose optimally.

C)a consequence of choosing optimally.

D)always observed prior to, but is not casually related to, optimal choice.

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) The results of this experiment suggest that the ability to correctly identify optimal game strategy is:

A)not necessary to choose optimally.

B)required to choose optimally.

C)a consequence of choosing optimally.

D)always observed prior to, but is not casually related to, optimal choice.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) Bechara et al. (1997) studied patients with brain damage in which of these areas?

A)Wernicke's area in the left temporal lobe

B)the prefrontal cortex

C)the amygdala

D)the hippocampus

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) Bechara et al. (1997) studied patients with brain damage in which of these areas?

A)Wernicke's area in the left temporal lobe

B)the prefrontal cortex

C)the amygdala

D)the hippocampus

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which statement is an example of interpreting orderly changes in language development as a result of emerging cognitive skills?

A)The universality of grammar rules suggests the presence on an innate language acquisition device.

B)In infants acquiring language, sentences at first are short (e.g., two words) because working memory has yet to fully develop.

C)Language acquisition progresses in orderly stages only if critical environmental components, such as continued social interaction, are present.

D)Maturing infants imitate the sounds that they hear, in part due to reinforcement from their parents.

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which statement is an example of interpreting orderly changes in language development as a result of emerging cognitive skills?

A)The universality of grammar rules suggests the presence on an innate language acquisition device.

B)In infants acquiring language, sentences at first are short (e.g., two words) because working memory has yet to fully develop.

C)Language acquisition progresses in orderly stages only if critical environmental components, such as continued social interaction, are present.

D)Maturing infants imitate the sounds that they hear, in part due to reinforcement from their parents.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which is the BEST reason why the research question posed in Scenario I could not be answered by studying infants' acquisition of the English language and comparing it to infants' acquisition of the Spanish language in American-born bilingual homes?

A)Language and cognitive development remain confounded in these groups.

B)The two groups differ on many potential third variables that could affect rates of language acquisition.

C)English and Spanish are too similar linguistically for meaningful differences in language acquisition to occur.

D)The linguistic expertise of the parents in the two groups may differ.

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Which is the BEST reason why the research question posed in Scenario I could not be answered by studying infants' acquisition of the English language and comparing it to infants' acquisition of the Spanish language in American-born bilingual homes?

A)Language and cognitive development remain confounded in these groups.

B)The two groups differ on many potential third variables that could affect rates of language acquisition.

C)English and Spanish are too similar linguistically for meaningful differences in language acquisition to occur.

D)The linguistic expertise of the parents in the two groups may differ.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) What can be accurately inferred from Scenario II?

A)The patients with brain damage lacked the ability to respond emotionally to wins and losses.

B)All other things being equal, the patients with brain damage had a much stronger behavioralpreference for the larger reward than the control participants.

C)The patients with brain damage had a much stronger emotional response to wins than losses.

D)The likelihood of losses leading up to a choice elicited a blunted emotional response in thepatients with brain damage.

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) What can be accurately inferred from Scenario II?

A)The patients with brain damage lacked the ability to respond emotionally to wins and losses.

B)All other things being equal, the patients with brain damage had a much stronger behavioralpreference for the larger reward than the control participants.

C)The patients with brain damage had a much stronger emotional response to wins than losses.

D)The likelihood of losses leading up to a choice elicited a blunted emotional response in thepatients with brain damage.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Snedeker et al. (2007) studied the acquisition of English as a second language in preschool children adopted from China. In trying to disentangle the role of linguistic and cognitive development on language acquisition, which of these would serve as the most appropriate control group?

A)the acquisition of English by Chinese teens who previously had no exposure to the English language

B)the acquisition of Mandarin by American-born preschoolers adopted into Chinese families

C)the acquisition of Mandarin over the first two years of life in Chinese-born infants.

D)the acquisition of English as a first language in Chinese infants adopted into American families.

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Snedeker et al. (2007) studied the acquisition of English as a second language in preschool children adopted from China. In trying to disentangle the role of linguistic and cognitive development on language acquisition, which of these would serve as the most appropriate control group?

A)the acquisition of English by Chinese teens who previously had no exposure to the English language

B)the acquisition of Mandarin by American-born preschoolers adopted into Chinese families

C)the acquisition of Mandarin over the first two years of life in Chinese-born infants.

D)the acquisition of English as a first language in Chinese infants adopted into American families.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

Scenario II

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) Which of these was NOT a dependent variable?

A)GSR

B)deck selection

C)programmed loss amount

D)verbal reports about game strategy

Scenario II is based on and presents results consistent with the following study:

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293-1295. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara et al. (1997) studied risky decision making on a gambling task in patients with brain damage in an area critically involved in executive functions such as planning and decision making. They compared this performance with the performance of control participants without brain damage. All participants were given a starting bankroll of $2,000 in facsimile dollars. In the baseline condition, participants chose cards from among four decks. Selecting cards from Decks A and B sometimes resulted in a win of $100. Selecting cards from Decks C and D sometimes resulted in a win of $50. No losses were incurred in this condition. In the subsequent experimental condition, however, some cards in all decks produced losses. The losses in Decks A and B were large and occurred frequently enough to possibly result in bankruptcy. The losses in Decks C and D were considerably smaller. Bechara et al. measured deck selection and the galvanic skin response (GSR) both prior to (anticipatory) and after (post-outcome) turning over each card.

In the baseline condition, all participants in both groups showed a clear preference for Decks A and B. Both groups showed small but reliable anticipatory and post-outcome GSRs. In the experimental condition, with continued play the controls exhibited a clear preference for Decks C and D, while the patients continued to play more from Decks A and B. Relative to the baseline condition, controls exhibited a much larger anticipatory GSR prior to each decision whereas the patients' anticipatory GSR was small and similar to that obtained under the baseline condition. The post-outcome GSRs were similar in the two groups and occurred to both wins and losses.

Interestingly, the investigator systematically interrupted play during the experimental condition and asked all participants if they had developed a game strategy. With continued play, most of the control participants labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Among the patients with brain damage, only half eventually labeled Decks A and B as "the bad decks." Remarkably, in both groups this realization did not affect game play. The minority of the control group who did not express a negative opinion about Decks A and B nevertheless tended to avoid those decks. Similarly, the patients who acknowledged that Decks C and D were risky nevertheless preferred those decks.

(Scenario II) Which of these was NOT a dependent variable?

A)GSR

B)deck selection

C)programmed loss amount

D)verbal reports about game strategy

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

Scenario I

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Figure 9.1 shows the number of verbs, expressed as a percentage of total English vocabulary, between 6 and 24 months of exposure to the English language in internationally adopted preschoolers from China and monolingual infants. Four fabricated sets of data (labeled A-D) are shown. Which data set provides the most support for the contention that cognitive factors play a role in language development?

A)data set A

B)data set B

C)data set C

D)data set D

Scenario I is based on and presents results consistent with the following studies:

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2012). Disentangling the effects of cognitive development and linguistic expertise: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of English in internationally-adopted children. Cognitive Psychology, 65(1), 39-76. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.01.004

Snedeker, J., Geren, J., & Shafto, C. L. (2007). Starting over: International adoption as a natural experiment in language development. Psychological Science, 18(1), 79-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01852.x

Language development occurs in orderly stages, beginning with one-word utterances and progressing to two-word utterances, simple sentences containing function morphemes, and the emergence of grammatical rules. Psycholinguists have attempted to determine if language development is a consequence of cognitive development or if it reflects linguistic processes that occur independently of general cognitive development. Studies on the acquisition of a second language in internationally adopted children have provided insight into this research question. In a series of studies, Snedeker et al. (2007, 2012) studied the acquisition of the English language in adopted preschoolers from China. These children had no exposure to the English language before being adopted by families in the United States.

Figure 9.1

(Scenario I) Figure 9.1 shows the number of verbs, expressed as a percentage of total English vocabulary, between 6 and 24 months of exposure to the English language in internationally adopted preschoolers from China and monolingual infants. Four fabricated sets of data (labeled A-D) are shown. Which data set provides the most support for the contention that cognitive factors play a role in language development?

A)data set A

B)data set B

C)data set C

D)data set D

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 13 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck