Essay

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Merck and Schering-Plough Merger: When Form Overrides Substance

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it really a duck? That is a question Johnson & Johnson might ask about a 2009 transaction involving pharmaceutical companies Merck and Schering-Plough. On August 7, 2009, shareholders of Merck and Company ("Merck") and Schering-Plough Corp. (Schering-Plough) voted overwhelmingly to approve a $41.1 billion merger of the two firms. With annual revenues of $42.4 billion, the new Merck will be second in size only to global pharmaceutical powerhouse Pfizer Inc.

At closing on November 3, 2009, Schering-Plough shareholders received $10.50 and 0.5767 of a share of the common stock of the combined company for each share of Schering-Plough stock they held, and Merck shareholders received one share of common stock of the combined company for each share of Merck they held. Merck shareholders voted to approve the merger agreement, and Schering-Plough shareholders voted to approve both the merger agreement and the issuance of shares of common stock in the combined firms. Immediately after the merger, the former shareholders of Merck and Schering-Plough owned approximately 68 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of the shares of the combined companies.

The motivation for the merger reflects the potential for $3.5 billion in pretax annual cost savings, with Merck reducing its workforce by about 15 percent through facility consolidations, a highly complementary product offering, and the substantial number of new drugs under development at Schering-Plough. Furthermore, the deal increases Merck's international presence, since 70 percent of Schering-Plough's revenues come from abroad. The combined firms both focus on biologics (i.e., drugs derived from living organisms). The new firm has a product offering that is much more diversified than either firm had separately.

The deal structure involved a reverse merger, which allowed for a tax-free exchange of shares and for Schering-Plough to argue that it was the acquirer in this transaction. The importance of the latter point is explained in the following section.

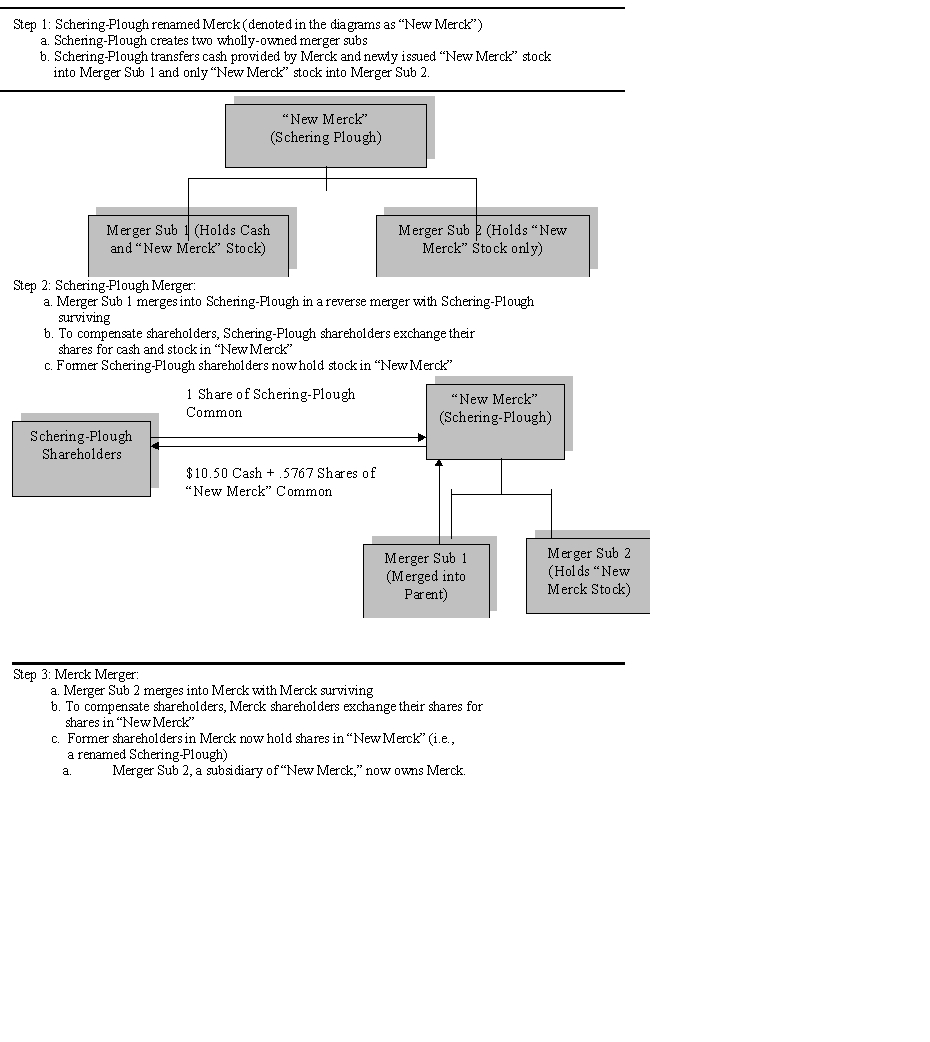

To implement the transaction, Schering-Plough created two merger subsidiaries . In reality, Merck acquired Schering-Plough.

Former shareholders of Schering-Plough and Merck become shareholders in the new Merck. The "New Merck" is simply Schering-Plough renamed Merck. This structure allows Schering-Plough to argue that no change in control occurred and that a termination clause in a partnership agreement with Johnson & Johnson should not be triggered. Under the agreement, J&J has the exclusive right to sell a rheumatoid arthritis drug it had developed called Remicade, and Schering-Plough has the exclusive right to sell the drug outside the United States, reflecting its stronger international distribution channel. If the change of control clause were triggered, rights to distribute the drug outside the United States would revert back to J&J. Remicade represented $2.1 billion or about 20 percent of Schering-Plough's 2008 revenues and about 70 percent of the firm's international revenues. Consequently, retaining these revenues following the merger was important to both Merck and Schering-Plough.

The multi-step process for implementing this transaction is illustrated in the following diagrams. From a legal perspective, all these actions occur concurrently.  Concluding Comments

Concluding Comments

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck's chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough's CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm's board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough's board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How did the use of a reverse merger facilitate the transaction?

Correct Answer:

Verified

The use of a reverse merger enabled the ...View Answer

Unlock this answer now

Get Access to more Verified Answers free of charge

Correct Answer:

Verified

View Answer

Unlock this answer now

Get Access to more Verified Answers free of charge

Q2: Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions<br>Consolidation in

Q30: From the viewpoint of the seller or

Q41: Taxes are an important consideration in almost

Q70: As a general rule, a transaction is

Q76: The IRS generally views forward triangular cash

Q90: Tax-free reorganizations require that substantially all of

Q95: Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions<br> <img

Q100: Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions<br>JDS Uniphase-SDL

Q108: Tax free reorganizations generally require that all

Q114: Transactions may be partially taxable if the