Exam 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities108 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment103 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market: Common Takeover Tactics, anti-Takeover Defenses, and Corporate Governance126 Questions

Exam 4: Planning,developing Business,and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process109 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 3 to 10 of the Acquisition Process106 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, acquisitions, and Business Alliances103 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics81 Questions

Exam 8: Relative,asset-Oriented,and Real Option Valuation Basics84 Questions

Exam 9: Applying Financial Models to Value, structure, and Negotiate Mergers and Acquisitions92 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation of Privately Held Companies97 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal: Payment and Legal Considerations112 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal: Tax and Accounting Considerations97 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal: Private Equity, hedge Funds, and Other Sources of Funds121 Questions

Exam 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics98 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, partnerships, strategic Alliances, and Licensing113 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies: Divestitures, spin-Offs, carve-Outs, split-Ups, and Split-Offs119 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies: Bankruptcy Reorganization and Liquidation80 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Analysis and Valuation89 Questions

Select questions type

The adjusted present value approach takes into account the effects of leverage on risk as debt is repaid.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (37)

(37)

In the presence of taxes,firms are often less leveraged than they should be,given the potentially large tax benefits associated with debt.Firms can increase market value by increasing leverage to the point at which the additional contribution of the tax shield to the firm's market value begins to decline.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (39)

(39)

Using the cost of capital method to value an LBO involves which of the following steps?

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Kinder Morgan Buyout Raises Ethical Questions

In the largest management buyout in U.S. history at that time, Kinder Morgan Inc.'s management proposed to take the oil and gas pipeline firm private in 2006 in a transaction that valued the firm's outstanding equity at $13.5 billion. Under the proposal, chief executive Richard Kinder and other senior executives would contribute shares valued at $2.8 billion to the newly private company. An additional $4.5 billion would come from private equity investors, including Goldman Sachs Capital partners, American International Group Inc., and the Carlyle Group. Including assumed debt, the transaction was valued at about $22 billion. The transaction also was notable for the governance and ethical issues it raised. Reflecting the struggles within the corporation, the deal did not close until mid-2007.

The top management of Kinder Morgan Inc. waited more than two months before informing the firm's board of its desire to take the company private. It is customary for boards governing firms whose managements are interested in buying out public shareholders to create a committee within the board consisting of independent board members to solicit other bids. While the Kinder Morgan board did eventually create such a committee, the board's lack of awareness of the pending management proposal gave management an important lead over potential bidders in structuring a proposal. By being involved early on in the process, a board has more time to negotiate terms more favorable to shareholders. The transaction also raised questions about the potential conflicts of interest in cases where investment bankers who were hired to advise management and the board on the "fairness" of the offer price also were potential investors in the buyout.

Kinder Morgan's management hired Goldman Sachs in February 2006 to explore "strategic" options for the firm to enhance shareholder value. The leveraged buyout option was proposed by Goldman Sachs on March 7, followed by their proposal to become the primary investor in the LBO on April 5. The management buyout group hired a number of law firms and other investment banks as advisors and discussed the proposed buyout with credit-rating firms to assess how much debt the firm could support without experiencing a downgrade in its credit rating.

On May 13, 2006, the full board was finally made aware of the proposal. The board immediately demanded that a standstill agreement that had been signed by Richard Kinder, CEO and leader of the buyout group, be terminated. The agreement did not permit the firm to talk to any alternative bidders for a period of 90 days. While investment banks and buyout groups often propose such an agreement to ensure that they can perform adequate due diligence, this extended period is not necessarily in the interests of the firm's shareholders because it puts alternative suitors coming in later at a distinct disadvantage. Later bidders simply lack sufficient time to make an adequate assessment of the true value of the target and structure their own proposals. In this way, the standstill agreement could discourage alternative bids for the business.

A special committee of the board was set up to negotiate with the management buyout group, and it was ultimately able to secure a $107.50 per share price for the firm, significantly higher than the initial offer. The discussions were rumored to have been very contentious due to the board's annoyance with the delay in informing them. Reflecting the strong financial performance of the firm and an improving equity market, Kinder Morgan raised $2.4 billion in early 2011 in the largest private equity-backed IPO in history. The majority of the IPO proceeds were paid out to the firm's private equity investors as a dividend.

Berman and Sender, 2006

Financing LBOs--The SunGard Transaction

With their cash hoards accumulating at an unprecedented rate, there was little that buyout firms could do but to invest in larger firms. Consequently, the average size of LBO transactions grew significantly during 2005. In a move reminiscent of the blockbuster buyouts of the late 1980s, seven private investment firms acquired 100 percent of the outstanding stock of SunGard Data Systems Inc. (SunGard) in late 2005. SunGard is a financial software firm known for providing application and transaction software services and creating backup data systems in the event of disaster. The company's software manages 70 percent of the transactions made on the Nasdaq stock exchange, but its biggest business is creating backup data systems in case a client's main systems are disabled by a natural disaster, blackout, or terrorist attack. Its large client base for disaster recovery and back-up systems provides a substantial and predictable cash flow.

SunGard's new owners include Silver lake Partners, Bain Capital LLC, The Blackstone Group L.P., Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., Providence Equity Partners Inc. and Texas Pacific Group. Buyout firms in 2005 tended to band together to spread the risk of a deal this size and to reduce the likelihood of a bidding war. Indeed, with SunGard, there was only one bidder, the investor group consisting of these seven firms.

The software side of SunGard is believed to have significant growth potential, while the disaster-recovery side provides a large stable cash flow. Unlike many LBOs, the deal was announced as being all about growth of the financial services software side of the business. The deal is structured as a merger, since SunGard would be merged into a shell corporation created by the investor group for acquiring SunGard. Going private, allows SunGard to invest heavily in software without being punished by investors, since such investments are expensed and reduce reported earnings per share. Going private also allows the firm to eliminate the burdensome reporting requirements of being a public company.

The buyout represented potentially a significant source of fee income for the investor group. In addition to the 2 percent management fees buyout firms collect from investors in the funds they manage, they receive substantial fee income from each investment they make on behalf of their funds. For example, the buyout firms receive a 1 percent deal completion fee, which is more than $100 million in the SunGard transaction. Buyout firms also receive fees paid for by the target firm that is "going private" for arranging financing. Moreover, there are also fees for conducting due diligence and for monitoring the ongoing performance of the firm taken private. Finally, when the buyout firms exit their investments in the target firm via a sale to a strategic buyer or a secondary IPO, they receive 20 percent (i.e., so-called carry fee) of any profits.

Under the terms of the agreement, SunGard shareholders received $36 per share, a 14 percent premium over the SunGard closing price as of the announcement date of March 28, 2005, and 40 percent more than when the news first leaked about the deal a week earlier. From the SunGard shareholders' perspective, the deal is valued at $11.4 billion dollars consisting of $10.9 billion for outstanding shares and "in-the-money" options (i.e., options whose exercise price is less than the firm's market price per share) plus $500 million in debt on the balance sheet.

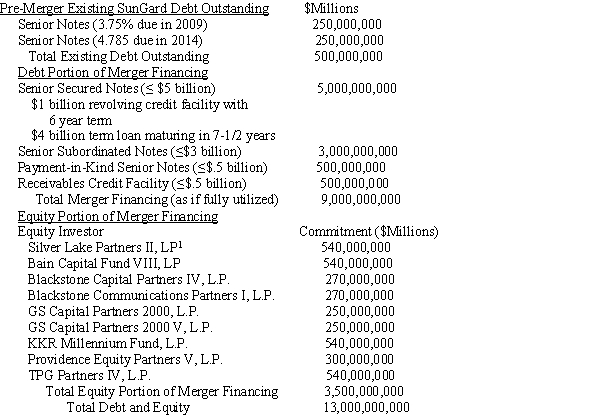

The seven equity investors provided $3.5 billion in capital with the remainder of the purchase price financed by commitments from a lending consortium consisting of Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., and Deutsche Bank. The purpose of the loans is to finance the merger, repay or refinance SunGard's existing debt, provide ongoing working capital, and pay fees and expenses incurred in connection with the merger. The total funds necessary to complete the merger and related fees and expenses is approximately $11.3 billion, consisting of approximately $10.9 billion to pay SunGard's stockholders and about $400.7 million to pay fees and expenses related to the merger and the financing arrangements. Note that the fees that are to be financed comprise almost 4 percent of the purchase price. Ongoing working capital needs and capital expenditures required obtaining commitments from lenders well in excess of $11.3 billion.

The merger financing consists of several tiers of debt and "credit facilities." Credit facilities are arrangements for extending credit. The senior secured debt and senior subordinated debt are intended to provide "permanent" or long-term financing. Senior debt covenants included restrictions on new borrowing, investments, sales of assets, mergers and consolidations, prepayments of subordinated indebtedness, capital expenditures, liens and dividends and other distributions, as well as a minimum interest coverage ratio and a maximum total leverage ratio.

If the offering of notes is not completed on or prior to the closing, the banks providing the financing have committed to provide up to $3 billion in loans under a senior subordinated bridge credit facility. The bridge loans are intended as a form of temporary financing to satisfy immediate cash requirements until permanent financing can be arranged. A special purpose SunGard subsidiary will purchase receivables from SunGard, with the purchases financed through the sale of the receivables to the lending consortium. The lenders subsequently finance the purchase of the receivables by issuing commercial paper, which is repaid as the receivables are collected. The special purpose subsidiary is not shown on the SunGard balance sheet. Based on the value of receivables at closing, the subsidiary could provide up to $500 million. The obligation of the lending consortium to buy the receivables will expire on the sixth anniversary of the closing of the merger.

The following table provides SunGard's post-merger proforma capital structure. Note that the proforma capital structure is portrayed as if SunGard uses 100 percent of bank lending commitments. Also, note that individual LBO investors may invest monies from more than one fund they manage. This may be due to the perceived attractiveness of the opportunity or the limited availability of money in any single fund. Of the $9 billion in debt financing, bank loans constitute 56 percent and subordinated or mezzanine debt comprises represents 44 percent.

SunGard Proforma Capital Structure  1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-SunGard is a software company with relatively few tangible assets.Yet,the ratio of debt to equity of almost 5 to 1.Why do you think lenders would be willing to engage in such a highly leveraged transaction for a firm of this type?

1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-SunGard is a software company with relatively few tangible assets.Yet,the ratio of debt to equity of almost 5 to 1.Why do you think lenders would be willing to engage in such a highly leveraged transaction for a firm of this type?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

As the LBO's extremely high debt level is reduced,the cost of equity needs to be adjusted to reflect the decline in risk,as measured by the firm's unlevered beta.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (31)

(31)

Which of the following are steps often found in developing a LBO model?

(Multiple Choice)

4.7/5  (32)

(32)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Cerberus Capital Management Acquires Chrysler Corporation

According to the terms of the transaction, Cerberus would own 80.1 percent of Chrysler's auto manufacturing and financial services businesses in exchange for $7.4 billion in cash. Daimler would continue to own 19.9 percent of the new business, Chrysler Holdings LLC. Of the $7.4 billion, Daimler would receive $1.35 billion while the remaining $6.05 billion would be invested in Chrysler (i.e., $5.0 billion is to be invested in the auto manufacturing operation and $1.05 billion in the finance unit). Daimler also agreed to pay to Cerberus $1.6 billion to cover Chrysler's long-term debt and cumulative operating losses during the four months between the signing of the merger agreement and the actual closing. In acquiring Chrysler, Cerberus assumed responsibility for an estimated $18 billion in unfunded retiree pension and medical benefits. Daimler also agreed to loan Chrysler Holdings LLC $405 million.

The transaction is atypical of those involving private equity investors, which usually take public firms private, expecting to later sell them for a profit. The private equity firm pays for the acquisition by borrowing against the firm's assets or cash flow. However, the estimated size of Chrysler's retiree health-care liabilities and the uncertainty of future cash flows make borrowing impractical. Therefore, Cerberus agreed to invest its own funds in the business to keep it running while it restructured the business.

By going private, Cerberus would be able to focus on the long-term without the disruption of meeting quarterly earnings reports. Cerberus was counting on paring retiree health-care liabilities through aggressive negotiations with the United Auto Workers (UAW). Cerberus sought a deal similar to what the UAW accepted from Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in late 2006. Under this agreement, the management of $1.2 billion in health-care liabilities was transferred to a fund managed by the UAW, with Goodyear contributing $1 billion in cash and Goodyear stock. By transferring responsibility for these liabilities to the UAW, Chrysler believed that it would be able to cut in half the $30 dollar per hour labor cost advantage enjoyed by Toyota. Cerberus also expected to benefit from melding Chrysler's financial unit with Cerberus's 51 percent ownership stake in GMAC, GM's former auto financing business. By consolidating the two businesses, Cerberus hoped to slash cost by eliminating duplicate jobs, combining overlapping operations such as data centers and field offices, and increasing the number of loans generated by combining back-office operations.

However, the 2008 credit market meltdown, severe recession, and subsequent free fall in auto sales threatened the financial viability of Chrysler, despite an infusion of U.S. government capital, and its leasing operations as well as GMAC. GMAC applied for commercial banking status to be able to borrow directly from the U.S. Federal Reserve. In late 2008, the U.S. Treasury purchased $6 billion in GMAC preferred stock to provide additional capital to the financially ailing firm. To avoid being classified as a bank holding company under direct government supervision, Cerberus reduced its ownership in 2009 to 14.9 percent of voting stock and 33 percent of total equity by distributing equity stakes to its coinvestors in GMAC. By surrendering its controlling interest in GMAC, it is less likely that Cerberus would be able to realize anticipated cost savings by combining the GMAC and Chrysler Financial operations. In early 2009, Chrysler entered into negotiations with Italian auto maker Fiat to gain access to the firm's technology in exchange for a 20 percent stake in Chrysler.

and Answers:

-Cite examples of economies of scale and scope?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Pacific Investors Acquires California Kool in a Leveraged Buyout

Pacific Investors (PI) is a small private equity limited partnership with $3 billion under management. The objective of the fund is to give investors at least a 30-percent annual average return on their investment by judiciously investing these funds in highly leveraged transactions. PI has been able to realize such returns over the last decade because of its focus on investing in industries that have slow but predictable growth in cash flow, modest capital investment requirements, and relatively low levels of research and development spending. In the past, PI made several lucrative investments in the contract packaging industry, which provides packaging for beverage companies that produce various types of noncarbonated and carbonated beverages. Because of its commitments to its investors, PI likes to liquidate its investments within four to six years of the initial investment through a secondary public offering or sale to a strategic investor.

Following its past success in the industry, PI currently is negotiating with California Kool (CK), a privately owned contract beverage packaging company with the technology required to package many types of noncarbonated drinks. CK's 2003 revenue and net income are $190.4 million and $5.9 million, respectively. With a reputation for effective management, CK is a medium-sized contract packaging company that owns its own plant and equipment and has a history of continually increasing cash flow. The company also has significant unused excess capacity, suggesting that production levels can be increased without substantial new capital spending.

The owners of CK are demanding a purchase price of $70 million. This is denoted on the balance sheet (see Table 13-15 at the end of the case) as a negative entry in additional paid-in capital. This price represents a multiple of 11.8 times 2003's net income, almost twice the multiple for comparable publicly traded companies. Despite the "rich" multiple, PI believes that it can finance the transaction through an equity investment of $25 million and $47 million in debt. The equity investment consists of $3 million in common stock, with PI's investors and CK's management each contributing $1.5 million. Debt consists of a $12 million revolving loan to meet immediate working capital requirements, $20 million in senior bank debt secured by CK's fixed assets, and $15 million in a subordinated loan from a pension fund. The total cost of acquiring CK is $72 million, $70 million paid to the owners of CK and $2 million in legal and accounting fees.

As indicated on Table 13-15, the change in total liabilities plus shareholders' equity (i.e., total sources of funds or cash inflows) must equal the change in total assets (i.e., total uses of funds or cash outflows). Therefore, as shown in the adjustments column, total liabilities increase by $47 million in total borrowings and shareholders' equity declines by $45 million (i.e., $25 million in preferred and common equity provided by investors less $70 million paid to CK owners). The excess of sources over uses of $2 million is used to finance legal and accounting fees incurred in closing the transaction. Consequently, total assets increase by $2 million and total liabilities plus shareholders' equity increase by $2 million between the pre- and postclosing balance sheets as shown in the adjustments column.hasi1 ΔTotal assets = ΔTotal liabilities + ΔShareholders' equity: $2 million = $47 million -$45 million = $2 million.

Revenue for CK is projected to grow at 4.5 percent annually through the foreseeable future. Operating expenses and sales, general, and administrative expenses as a percent of sales are expected to decline during the first three years of operation due to aggressive cost cutting and the introduction of new management and engineering processes. Similarly, improved working capital management results in significant declines in working capital as a percent of sales during the first year of operation. Gross fixed assets as percent of sales is held constant at its 2003 level during the forecast period, reflecting reinvestment requirements to support the projected increase in net revenue. Equity cash flow adjusted to include cash generated in excess of normal operating requirements (i.e., denoted by the change in investments available for sale) is expected to reach $8.5 million annually by 2010. Using the cost of capital method, the cost of equity declines in line with the reduction in the firm's beta as the debt is repaid from 26 percent in 2004 to 16.5 percent in 2010. In contrast, the adjusted present value method employs a constant unlevered COE of 17 percent.

The deal would appear to make sense from the standpoint of PI, since the projected average annual internal rates of return (IRRs) for investors exceed PI's minimum desired 30 percent rate of return in all scenarios considered between 2007 and 2009 (see Table 13-13). This is the period during which investors would like to "cash out." The rates of return scenarios are calculated assuming the business can be sold at different multiples of adjusted equity cash flow in the year in which the business is assumed to be sold. Consequently, IRRs are calculated using the cash outflow (initial equity investment in the business) in the first year offset by any positive equity cash flow from operations generated in the first year, equity cash flows for each subsequent year, and the sum of equity cash flow in the year in which the business is sold or taken public plus the estimated sale value (e.g., eight times equity cash flow) in that year. Adjusted equity cash flow includes free cash flow generated from operations and the increase in "investments available for sale." Such investments represent cash generated in excess of normal operating requirements; and as such, this cash is available to LBO investors.

The actual point at which CK would either be taken public, sold to a strategic investor, or sold to another LBO fund depends on stock market conditions, CK's leverage relative to similar firms in the industry, and cash flow performance as compared to the plan. Discounted cash flow analysis also suggests that PI should do the deal, since the total present value of adjusted equity cash flow of $57.2 million using the CC method is more than twice the magnitude of the initial equity investment. At $56 million, the APV method results in a slightly lower estimate of total present value. See Tables 13-14,13-15, and 13-16 for the income, balance-sheet, and cash-flow statements, respectively, associated with this transaction. Exhibits 13-1 and 13-2 illustrate the calculation of present value of the transaction based on the cost of capital and the adjusted present value methods, respectively. Note the actual Excel spreadsheets and formulas used to create these financial tables are available on the CD-ROM accompanying this book in a worksheet, Excel-Based Leveraged Buyout Valuation and Structuring Model.

-What criteria did Pacific Investors (PI)use to select California Kool (CK)as a target for an LBO? Why were these criteria employed?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (34)

(34)

An LBO can be valued from the perspective of which of the following?

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (27)

(27)

In the adjusted present value method,the levered cost of equity is used for discounting cash flows during the period in which the capital structure is changing and the weighted-average cost of capital for discounting during the terminal period.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (24)

(24)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Cox Enterprises Offers to Take Cox Communications Private

In an effort to take the firm private, Cox Enterprises announced on August 3, 2004 a proposal to buy the remaining 38% of Cox Communications' shares that they did not currently own for $32 per share. The deal is valued at $7.9 billion and represented a 16% premium to Cox Communication's share price at that time. Cox Communications would become a subsidiary of Cox Enterprises and would continue to operate as an autonomous business. In response to the proposal, the Cox Communications Board of Directors formed a special committee of independent directors to consider the proposal. Citigroup Global Markets and Lehman Brothers Inc. have committed $10 billion to the deal. Cox Enterprises would use $7.9 billion for the tender offer, with the remaining $2.1 billion used for refinancing existing debt and to satisfy working capital requirements.

Cable service firms have faced intensified competitive pressures from satellite service providers DirecTV Group and EchoStar communications. Moreover, telephone companies continue to attack cable's high-speed Internet service by cutting prices on high-speed Internet service over phone lines. Cable firms have responded by offering a broader range of advanced services like video-on-demand and phone service. Since 2000, the cable industry has invested more than $80 billion to upgrade their systems to provide such services, causing profitability to deteriorate and frustrating investors. In response, cable company stock prices have fallen. Cox Enterprises stated that the increasingly competitive cable industry environment makes investment in the cable industry best done through a private company structure.

::

-Why did the board feel that it was appropriate to set up special committee of independent board directors?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (26)

(26)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

RJR NABISCO GOES PRIVATE-

KEY SHAREHOLDER AND PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES

Background

The largest LBO in history is as well known for its theatrics as it is for its substantial improvement in shareholder value. In October 1988, H. Ross Johnson, then CEO of RJR Nabisco, proposed an MBO of the firm at $75 per share. His failure to inform the RJR board before publicly announcing his plans alienated many of the directors. Analysts outside the company placed the breakup value of RJR Nabisco at more than $100 per share-almost twice its then current share price. Johnson's bid immediately was countered by a bid by the well-known LBO firm, Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts (KKR), to buy the firm for $90 per share (Wasserstein, 1998). The firm's board immediately was faced with the dilemma of whether to accept the KKR offer or to consider some other form of restructuring of the company. The board appointed a committee of outside directors to assess the bid to minimize the appearance of a potential conflict of interest in having current board members, who were also part of the buyout proposal from management, vote on which bid to select.

The bidding war soon escalated with additional bids coming from Forstmann Little and First Boston, although the latter's bid never really was taken very seriously. Forstmann Little later dropped out of the bidding as the purchase price rose. Although the firm's investment bankers valued both the bids by Johnson and KKR at about the same level, the board ultimately accepted the KKR bid. The winning bid was set at almost $25 billion-the largest transaction on record at that time and the largest LBO in history. Banks provided about three-fourths of the $20 billion that was borrowed to complete the transaction. The remaining debt was supplied by junk bond financing. The RJR shareholders were the real winners, because the final purchase price constituted a more than 100% return from the $56 per share price that existed just before the initial bid by RJR management.

Aggressive pricing actions by such competitors as Phillip Morris threatened to erode RJR Nabisco's ability to service its debt. Complex securities such as "increasing rate notes," whose coupon rates had to be periodically reset to ensure that these notes would trade at face value, ultimately forced the credit rating agencies to downgrade the RJR Nabisco debt. As market interest rates climbed, RJR Nabisco did not appear to have sufficient cash to accommodate the additional interest expense on the increasing return notes. To avoid default, KKR recapitalized the company by investing additional equity capital and divesting more than $5 billion worth of businesses in 1990 to help reduce its crushing debt load. In 1991, RJR went public by issuing more than $1 billion in new common stock, which placed about one-fourth of the firm's common stock in public hands.

When KKR eventually fully liquidated its position in RJR Nabisco in 1995, it did so for a far smaller profit than expected. KKR earned a profit of about $60 million on an equity investment of $3.1 billion. KKR had not done well for the outside investors who had financed more than 90% of the total equity investment in KKR. However, KKR fared much better than investors had in its LBO funds by earning more than $500 million in transaction fees, advisor fees, management fees, and directors' fees. The publicity surrounding the transaction did not cease with the closing of the transaction. Dissident bondholders filed suits alleging that the payment of such a large premium for the company represented a "confiscation" of bondholder wealth by shareholders.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

In any MBO, management is confronted by a potential conflict of interest. Their fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders is to take actions to maximize shareholder value; yet in the RJR Nabisco case, the management bid appeared to be well below what was in the best interests of shareholders. Several proposals have been made to minimize the potential for conflict of interest in the case of an MBO, including that directors, who are part of an MBO effort, not be allowed to participate in voting on bids, that fairness opinions be solicited from independent financial advisors, and that a firm receiving an MBO proposal be required to hold an auction for the firm.

The most contentious discussion immediately following the closing of the RJR Nabisco buyout centered on the alleged transfer of wealth from bond and preferred stockholders to common stockholders when a premium was paid for the shares held by RJR Nabisco common stockholders. It often is argued that at least some part of the premium is offset by a reduction in the value of the firm's outstanding bonds and preferred stock because of the substantial increase in leverage that takes place in LBOs.

Winners and Losers

RJR Nabisco shareholders before the buyout clearly benefited greatly from efforts to take the company private. However, in addition to the potential transfer of wealth from bondholders to stockholders, some critics of LBOs argue that a wealth transfer also takes place in LBO transactions when LBO management is able to negotiate wage and benefit concessions from current employee unions. LBOs are under greater pressure to seek such concessions than other types of buyouts because they need to meet huge debt service requirements.

:

-In your opinion,was the buyout proposal presented by Ross Johnson's management group in the best interests of the shareholders? Why? / Why not?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Financial buyers often will attempt to determine the highest amount of debt possible (i.e.,the borrowing capacity of the target firm)to maximize their equity contribution in order to maximize the IRR.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

Some analysts suggest that the problem of a variable discount rate can be avoided by separating the value of a firm's operations into two components: the firm's value as if it were debt free and the value of interest tax savings.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (32)

(32)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

RJR NABISCO GOES PRIVATE-

KEY SHAREHOLDER AND PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES

Background

The largest LBO in history is as well known for its theatrics as it is for its substantial improvement in shareholder value. In October 1988, H. Ross Johnson, then CEO of RJR Nabisco, proposed an MBO of the firm at $75 per share. His failure to inform the RJR board before publicly announcing his plans alienated many of the directors. Analysts outside the company placed the breakup value of RJR Nabisco at more than $100 per share-almost twice its then current share price. Johnson's bid immediately was countered by a bid by the well-known LBO firm, Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts (KKR), to buy the firm for $90 per share (Wasserstein, 1998). The firm's board immediately was faced with the dilemma of whether to accept the KKR offer or to consider some other form of restructuring of the company. The board appointed a committee of outside directors to assess the bid to minimize the appearance of a potential conflict of interest in having current board members, who were also part of the buyout proposal from management, vote on which bid to select.

The bidding war soon escalated with additional bids coming from Forstmann Little and First Boston, although the latter's bid never really was taken very seriously. Forstmann Little later dropped out of the bidding as the purchase price rose. Although the firm's investment bankers valued both the bids by Johnson and KKR at about the same level, the board ultimately accepted the KKR bid. The winning bid was set at almost $25 billion-the largest transaction on record at that time and the largest LBO in history. Banks provided about three-fourths of the $20 billion that was borrowed to complete the transaction. The remaining debt was supplied by junk bond financing. The RJR shareholders were the real winners, because the final purchase price constituted a more than 100% return from the $56 per share price that existed just before the initial bid by RJR management.

Aggressive pricing actions by such competitors as Phillip Morris threatened to erode RJR Nabisco's ability to service its debt. Complex securities such as "increasing rate notes," whose coupon rates had to be periodically reset to ensure that these notes would trade at face value, ultimately forced the credit rating agencies to downgrade the RJR Nabisco debt. As market interest rates climbed, RJR Nabisco did not appear to have sufficient cash to accommodate the additional interest expense on the increasing return notes. To avoid default, KKR recapitalized the company by investing additional equity capital and divesting more than $5 billion worth of businesses in 1990 to help reduce its crushing debt load. In 1991, RJR went public by issuing more than $1 billion in new common stock, which placed about one-fourth of the firm's common stock in public hands.

When KKR eventually fully liquidated its position in RJR Nabisco in 1995, it did so for a far smaller profit than expected. KKR earned a profit of about $60 million on an equity investment of $3.1 billion. KKR had not done well for the outside investors who had financed more than 90% of the total equity investment in KKR. However, KKR fared much better than investors had in its LBO funds by earning more than $500 million in transaction fees, advisor fees, management fees, and directors' fees. The publicity surrounding the transaction did not cease with the closing of the transaction. Dissident bondholders filed suits alleging that the payment of such a large premium for the company represented a "confiscation" of bondholder wealth by shareholders.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

In any MBO, management is confronted by a potential conflict of interest. Their fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders is to take actions to maximize shareholder value; yet in the RJR Nabisco case, the management bid appeared to be well below what was in the best interests of shareholders. Several proposals have been made to minimize the potential for conflict of interest in the case of an MBO, including that directors, who are part of an MBO effort, not be allowed to participate in voting on bids, that fairness opinions be solicited from independent financial advisors, and that a firm receiving an MBO proposal be required to hold an auction for the firm.

The most contentious discussion immediately following the closing of the RJR Nabisco buyout centered on the alleged transfer of wealth from bond and preferred stockholders to common stockholders when a premium was paid for the shares held by RJR Nabisco common stockholders. It often is argued that at least some part of the premium is offset by a reduction in the value of the firm's outstanding bonds and preferred stock because of the substantial increase in leverage that takes place in LBOs.

Winners and Losers

RJR Nabisco shareholders before the buyout clearly benefited greatly from efforts to take the company private. However, in addition to the potential transfer of wealth from bondholders to stockholders, some critics of LBOs argue that a wealth transfer also takes place in LBO transactions when LBO management is able to negotiate wage and benefit concessions from current employee unions. LBOs are under greater pressure to seek such concessions than other types of buyouts because they need to meet huge debt service requirements.

:

-How might bondholders and preferred stockholders have been hurt in the RJR Nabisco leveraged buyout?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

An LBO can be valued from the perspective of common equity investors only or all those who supply funds,including common and preferred investors and lenders.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

The expected cost of and probability of occurring of financial distress are easily forecasted.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

In applying the adjusted present value method,the present value of a highly leveraged transaction should reflect the present value of the firm without leverage plus the present value of tax savings plus the present value of expected financial distress.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Conventional capital budgeting procedures are of little use in valuing an LBO.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

Showing 21 - 40 of 98

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)