Exam 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities108 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment103 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market: Common Takeover Tactics, anti-Takeover Defenses, and Corporate Governance126 Questions

Exam 4: Planning,developing Business,and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process109 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 3 to 10 of the Acquisition Process106 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, acquisitions, and Business Alliances103 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics81 Questions

Exam 8: Relative,asset-Oriented,and Real Option Valuation Basics84 Questions

Exam 9: Applying Financial Models to Value, structure, and Negotiate Mergers and Acquisitions92 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation of Privately Held Companies97 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal: Payment and Legal Considerations112 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal: Tax and Accounting Considerations97 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal: Private Equity, hedge Funds, and Other Sources of Funds121 Questions

Exam 14: Highly Leveraged Transactions: Lbo Valuation and Modeling Basics98 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, partnerships, strategic Alliances, and Licensing113 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies: Divestitures, spin-Offs, carve-Outs, split-Ups, and Split-Offs119 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies: Bankruptcy Reorganization and Liquidation80 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Analysis and Valuation89 Questions

Select questions type

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Cerberus Capital Management Acquires Chrysler Corporation

According to the terms of the transaction, Cerberus would own 80.1 percent of Chrysler's auto manufacturing and financial services businesses in exchange for $7.4 billion in cash. Daimler would continue to own 19.9 percent of the new business, Chrysler Holdings LLC. Of the $7.4 billion, Daimler would receive $1.35 billion while the remaining $6.05 billion would be invested in Chrysler (i.e., $5.0 billion is to be invested in the auto manufacturing operation and $1.05 billion in the finance unit). Daimler also agreed to pay to Cerberus $1.6 billion to cover Chrysler's long-term debt and cumulative operating losses during the four months between the signing of the merger agreement and the actual closing. In acquiring Chrysler, Cerberus assumed responsibility for an estimated $18 billion in unfunded retiree pension and medical benefits. Daimler also agreed to loan Chrysler Holdings LLC $405 million.

The transaction is atypical of those involving private equity investors, which usually take public firms private, expecting to later sell them for a profit. The private equity firm pays for the acquisition by borrowing against the firm's assets or cash flow. However, the estimated size of Chrysler's retiree health-care liabilities and the uncertainty of future cash flows make borrowing impractical. Therefore, Cerberus agreed to invest its own funds in the business to keep it running while it restructured the business.

By going private, Cerberus would be able to focus on the long-term without the disruption of meeting quarterly earnings reports. Cerberus was counting on paring retiree health-care liabilities through aggressive negotiations with the United Auto Workers (UAW). Cerberus sought a deal similar to what the UAW accepted from Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in late 2006. Under this agreement, the management of $1.2 billion in health-care liabilities was transferred to a fund managed by the UAW, with Goodyear contributing $1 billion in cash and Goodyear stock. By transferring responsibility for these liabilities to the UAW, Chrysler believed that it would be able to cut in half the $30 dollar per hour labor cost advantage enjoyed by Toyota. Cerberus also expected to benefit from melding Chrysler's financial unit with Cerberus's 51 percent ownership stake in GMAC, GM's former auto financing business. By consolidating the two businesses, Cerberus hoped to slash cost by eliminating duplicate jobs, combining overlapping operations such as data centers and field offices, and increasing the number of loans generated by combining back-office operations.

However, the 2008 credit market meltdown, severe recession, and subsequent free fall in auto sales threatened the financial viability of Chrysler, despite an infusion of U.S. government capital, and its leasing operations as well as GMAC. GMAC applied for commercial banking status to be able to borrow directly from the U.S. Federal Reserve. In late 2008, the U.S. Treasury purchased $6 billion in GMAC preferred stock to provide additional capital to the financially ailing firm. To avoid being classified as a bank holding company under direct government supervision, Cerberus reduced its ownership in 2009 to 14.9 percent of voting stock and 33 percent of total equity by distributing equity stakes to its coinvestors in GMAC. By surrendering its controlling interest in GMAC, it is less likely that Cerberus would be able to realize anticipated cost savings by combining the GMAC and Chrysler Financial operations. In early 2009, Chrysler entered into negotiations with Italian auto maker Fiat to gain access to the firm's technology in exchange for a 20 percent stake in Chrysler.

and Answers:

-What are the risks to this deal's eventual success? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (44)

(44)

Increased borrowing by a firm will,other things equal,increase its tax liability.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (42)

(42)

Which of the following are often viewed as disadvantages of the adjusted present value method?

(Multiple Choice)

4.9/5  (44)

(44)

The justification for the adjusted present value (APV)method reflects the theoretical notion that firm value should not be affected by the way in which it is financed.However,recent studies empirical suggest that for LBOs,the availability and cost of financing does indeed impact financing and investment decisions.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (25)

(25)

The present value of tax savings is irrelevant to the adjusted present value method.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (31)

(31)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

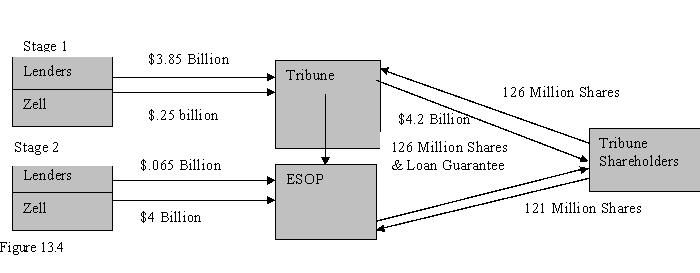

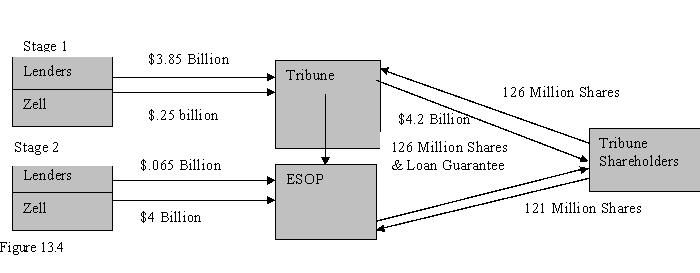

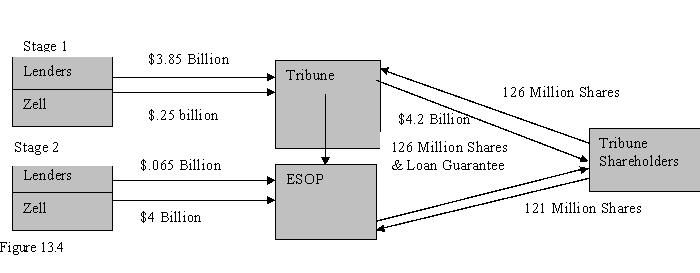

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).  Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-Comment on the fairness of this transaction to the various stakeholders involved.How would you apportion

the responsibility for the eventual bankruptcy of Tribune among Sam Zell and his advisors,the Tribune board,and the largely unforeseen collapse of the credit markets in late 2008? Be specific.

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-Comment on the fairness of this transaction to the various stakeholders involved.How would you apportion

the responsibility for the eventual bankruptcy of Tribune among Sam Zell and his advisors,the Tribune board,and the largely unforeseen collapse of the credit markets in late 2008? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.7/5  (42)

(42)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).  Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-What is the acquisition vehicle,post-closing organization,form of payment,form of acquisition,and tax

strategy described in this case study?

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-What is the acquisition vehicle,post-closing organization,form of payment,form of acquisition,and tax

strategy described in this case study?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (44)

(44)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Private Equity Firms Acquire Yellow Pages Business

Qwest Communications agreed to sell its yellow pages business, QwestDex, to a consortium led by the Carlyle Group and Welsh, Carson, Anderson and Stowe for $7.1 billion. In a two stage transaction, Qwest sold the eastern half of the yellow pages business for $2.75 billion in late 2002. This portion of the business included directories in Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Mexico, South Dakota, and North Dakota. The remainder of the business, Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming, was sold for $4.35 billion in late 2003. Caryle and Welsh Carson each put in $775 million in equity (about 21 percent of the total purchase price).

Qwest was in a precarious financial position at the time of the negotiation. The telecom was trying to avoid bankruptcy and needed the first stage financing to meet impending debt repayments due in late 2002. Qwest is a local phone company in 14 western states and one of the nation's largest long-distance carriers. It had amassed $26.5 billion in debt following a series of acquisitions during the 1990s.

The Carlyle Group has invested globally, mainly in defense and aerospace businesses, but it has also invested in companies in real estate, health care, bottling, and information technology. Welsh Carson focuses primarily on the communications and health care industries. While the yellow pages business is quite different from their normal areas of investment, both firms were attracted by its steady cash flow. Such cash flow could be used to trim debt over time and generate a solid return. The business' existing management team will continue to run the operation under the new ownership. Financing for the deal will come from J.P. Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Lehman Brothers, Wachovia Securities, and Deutsche Bank. The investment groups agreed to a two stage transaction to facilitate borrowing the large amounts required and to reduce the amount of equity each buyout firm had to invest. By staging the purchase, the lenders could see how well the operations acquired during the first stage could manage their debt load.

The new company will be the exclusive directory publisher for Qwest yellow page needs at the local level and will provide all of Qwest's publishing requirements under a fifty year contract. Under the arrangement, Qwest will continue to provide certain services to its former yellow pages unit, such as billing and information technology, under a variety of commercial services and transitional services agreements (Qwest: 2002).

:

-Why would it take five very large financial institutions to finance the transactions?

(Essay)

4.7/5  (29)

(29)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Financing Challenges in the Home Depot Supply Transaction

Buyout firms Bain Capital, Carlyle Group, and Clayton, Dubilier & Rice (CD&R) bid $10.3 billion in June 2007 to buy Home Depot Inc.'s HD Supply business. HD Supply represented a collection of small suppliers of construction products. Home Depot had announced earlier in the year that it planned to use the proceeds of the sale to pay for a portion of a $22.5 billion stock buyback.

Three banks, Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan Chase, and Merrill Lynch agreed to provide the firms with a $4 billion loan. The repayment of the loans was predicated on the ability of the buyout firms to improve significantly HD Supply's current cash flow. Such loans are normally made with the presumption that the they can be sold to investors, with the banks collecting fees from both the borrower and investor groups. However, by July, concern about the credit quality of subprime mortgages spread to the broader debt market and raised questions about the potential for default of loans made to finance highly leveraged transactions. The concern was particularly great for so-called "covenant-lite" loans for which the repayment terms were very lenient.

Fearing they would not be able to resell such loans to investors, the three banks involved in financing the HD Supply transaction wanted more financial protection. Additional protection, they reasoned, would make such loans more marketable to investors. They used the upheaval in the credit markets as a pretext for reopening negotiations on their previous financing commitments. Home Depot was willing to lower the selling price thereby reducing the amount of financing required by the buyout firms and was willing to guarantee payment in the event of default by the buyout firms. While Bain, Carlyle, and CD&R were willing to increase their cash investment and pay higher fees to the banks, they were unwilling to alter the original terms of the loans. Eventually the banks agreed to provide financing consisting of a $1 billion "covenant-lite" loan and a $1.3 billion "payment-in-kind" loan. Home Depot agreed to assume the loan payments on the $1 billion loan if the investor firms were to default and to lower the selling price to $8.5 billion for 87.5 percent of HD Supply, with Home Depot retaining the remaining 12.5 percent.

By the end of August, Home Depot had succeeded in raising the cash needed to help pay for its share repurchase, and the banks had reduced their original commitment of $4 billion in loans to $2.3 billion. While they had agreed to put more money into the transaction, the buyout firms had been successful in limiting the number of new restrictive covenants.

Case Study :

-Why did banks lower their lending standards in financing LBOs in 2006 and early 2007? How did the lax

standards contribute to their inability to sell the loans to investors? How did the inability to sell the loans once made curtail their future lending?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

Many analysts use the cost of capital method because of its relative simplicity.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

The DCF analysis solves for the present value of the firm,while the LBO analysis solves for the discount rate or internal rate of return.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (33)

(33)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Kinder Morgan Buyout Raises Ethical Questions

In the largest management buyout in U.S. history at that time, Kinder Morgan Inc.'s management proposed to take the oil and gas pipeline firm private in 2006 in a transaction that valued the firm's outstanding equity at $13.5 billion. Under the proposal, chief executive Richard Kinder and other senior executives would contribute shares valued at $2.8 billion to the newly private company. An additional $4.5 billion would come from private equity investors, including Goldman Sachs Capital partners, American International Group Inc., and the Carlyle Group. Including assumed debt, the transaction was valued at about $22 billion. The transaction also was notable for the governance and ethical issues it raised. Reflecting the struggles within the corporation, the deal did not close until mid-2007.

The top management of Kinder Morgan Inc. waited more than two months before informing the firm's board of its desire to take the company private. It is customary for boards governing firms whose managements are interested in buying out public shareholders to create a committee within the board consisting of independent board members to solicit other bids. While the Kinder Morgan board did eventually create such a committee, the board's lack of awareness of the pending management proposal gave management an important lead over potential bidders in structuring a proposal. By being involved early on in the process, a board has more time to negotiate terms more favorable to shareholders. The transaction also raised questions about the potential conflicts of interest in cases where investment bankers who were hired to advise management and the board on the "fairness" of the offer price also were potential investors in the buyout.

Kinder Morgan's management hired Goldman Sachs in February 2006 to explore "strategic" options for the firm to enhance shareholder value. The leveraged buyout option was proposed by Goldman Sachs on March 7, followed by their proposal to become the primary investor in the LBO on April 5. The management buyout group hired a number of law firms and other investment banks as advisors and discussed the proposed buyout with credit-rating firms to assess how much debt the firm could support without experiencing a downgrade in its credit rating.

On May 13, 2006, the full board was finally made aware of the proposal. The board immediately demanded that a standstill agreement that had been signed by Richard Kinder, CEO and leader of the buyout group, be terminated. The agreement did not permit the firm to talk to any alternative bidders for a period of 90 days. While investment banks and buyout groups often propose such an agreement to ensure that they can perform adequate due diligence, this extended period is not necessarily in the interests of the firm's shareholders because it puts alternative suitors coming in later at a distinct disadvantage. Later bidders simply lack sufficient time to make an adequate assessment of the true value of the target and structure their own proposals. In this way, the standstill agreement could discourage alternative bids for the business.

A special committee of the board was set up to negotiate with the management buyout group, and it was ultimately able to secure a $107.50 per share price for the firm, significantly higher than the initial offer. The discussions were rumored to have been very contentious due to the board's annoyance with the delay in informing them. Reflecting the strong financial performance of the firm and an improving equity market, Kinder Morgan raised $2.4 billion in early 2011 in the largest private equity-backed IPO in history. The majority of the IPO proceeds were paid out to the firm's private equity investors as a dividend.

Berman and Sender, 2006

Financing LBOs--The SunGard Transaction

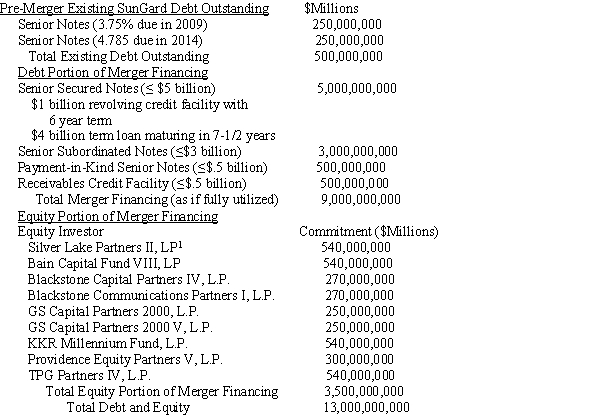

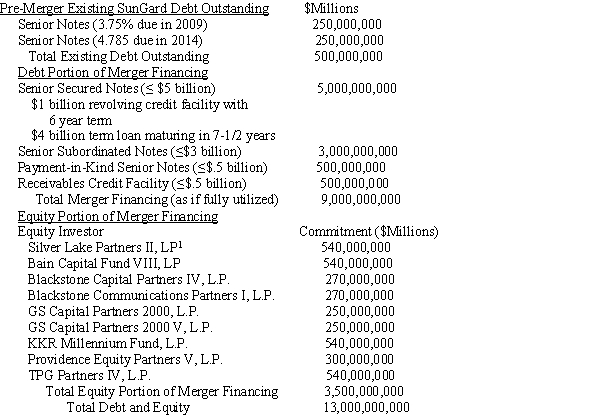

With their cash hoards accumulating at an unprecedented rate, there was little that buyout firms could do but to invest in larger firms. Consequently, the average size of LBO transactions grew significantly during 2005. In a move reminiscent of the blockbuster buyouts of the late 1980s, seven private investment firms acquired 100 percent of the outstanding stock of SunGard Data Systems Inc. (SunGard) in late 2005. SunGard is a financial software firm known for providing application and transaction software services and creating backup data systems in the event of disaster. The company's software manages 70 percent of the transactions made on the Nasdaq stock exchange, but its biggest business is creating backup data systems in case a client's main systems are disabled by a natural disaster, blackout, or terrorist attack. Its large client base for disaster recovery and back-up systems provides a substantial and predictable cash flow.

SunGard's new owners include Silver lake Partners, Bain Capital LLC, The Blackstone Group L.P., Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., Providence Equity Partners Inc. and Texas Pacific Group. Buyout firms in 2005 tended to band together to spread the risk of a deal this size and to reduce the likelihood of a bidding war. Indeed, with SunGard, there was only one bidder, the investor group consisting of these seven firms.

The software side of SunGard is believed to have significant growth potential, while the disaster-recovery side provides a large stable cash flow. Unlike many LBOs, the deal was announced as being all about growth of the financial services software side of the business. The deal is structured as a merger, since SunGard would be merged into a shell corporation created by the investor group for acquiring SunGard. Going private, allows SunGard to invest heavily in software without being punished by investors, since such investments are expensed and reduce reported earnings per share. Going private also allows the firm to eliminate the burdensome reporting requirements of being a public company.

The buyout represented potentially a significant source of fee income for the investor group. In addition to the 2 percent management fees buyout firms collect from investors in the funds they manage, they receive substantial fee income from each investment they make on behalf of their funds. For example, the buyout firms receive a 1 percent deal completion fee, which is more than $100 million in the SunGard transaction. Buyout firms also receive fees paid for by the target firm that is "going private" for arranging financing. Moreover, there are also fees for conducting due diligence and for monitoring the ongoing performance of the firm taken private. Finally, when the buyout firms exit their investments in the target firm via a sale to a strategic buyer or a secondary IPO, they receive 20 percent (i.e., so-called carry fee) of any profits.

Under the terms of the agreement, SunGard shareholders received $36 per share, a 14 percent premium over the SunGard closing price as of the announcement date of March 28, 2005, and 40 percent more than when the news first leaked about the deal a week earlier. From the SunGard shareholders' perspective, the deal is valued at $11.4 billion dollars consisting of $10.9 billion for outstanding shares and "in-the-money" options (i.e., options whose exercise price is less than the firm's market price per share) plus $500 million in debt on the balance sheet.

The seven equity investors provided $3.5 billion in capital with the remainder of the purchase price financed by commitments from a lending consortium consisting of Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., and Deutsche Bank. The purpose of the loans is to finance the merger, repay or refinance SunGard's existing debt, provide ongoing working capital, and pay fees and expenses incurred in connection with the merger. The total funds necessary to complete the merger and related fees and expenses is approximately $11.3 billion, consisting of approximately $10.9 billion to pay SunGard's stockholders and about $400.7 million to pay fees and expenses related to the merger and the financing arrangements. Note that the fees that are to be financed comprise almost 4 percent of the purchase price. Ongoing working capital needs and capital expenditures required obtaining commitments from lenders well in excess of $11.3 billion.

The merger financing consists of several tiers of debt and "credit facilities." Credit facilities are arrangements for extending credit. The senior secured debt and senior subordinated debt are intended to provide "permanent" or long-term financing. Senior debt covenants included restrictions on new borrowing, investments, sales of assets, mergers and consolidations, prepayments of subordinated indebtedness, capital expenditures, liens and dividends and other distributions, as well as a minimum interest coverage ratio and a maximum total leverage ratio.

If the offering of notes is not completed on or prior to the closing, the banks providing the financing have committed to provide up to $3 billion in loans under a senior subordinated bridge credit facility. The bridge loans are intended as a form of temporary financing to satisfy immediate cash requirements until permanent financing can be arranged. A special purpose SunGard subsidiary will purchase receivables from SunGard, with the purchases financed through the sale of the receivables to the lending consortium. The lenders subsequently finance the purchase of the receivables by issuing commercial paper, which is repaid as the receivables are collected. The special purpose subsidiary is not shown on the SunGard balance sheet. Based on the value of receivables at closing, the subsidiary could provide up to $500 million. The obligation of the lending consortium to buy the receivables will expire on the sixth anniversary of the closing of the merger.

The following table provides SunGard's post-merger proforma capital structure. Note that the proforma capital structure is portrayed as if SunGard uses 100 percent of bank lending commitments. Also, note that individual LBO investors may invest monies from more than one fund they manage. This may be due to the perceived attractiveness of the opportunity or the limited availability of money in any single fund. Of the $9 billion in debt financing, bank loans constitute 56 percent and subordinated or mezzanine debt comprises represents 44 percent.

SunGard Proforma Capital Structure  1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-Under what circumstances would SunGard refinance the existing $500 million in outstanding senior debt after the merger? Be specific.

1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-Under what circumstances would SunGard refinance the existing $500 million in outstanding senior debt after the merger? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.7/5  (33)

(33)

The riskiness of highly leveraged transactions declines overtime due to which of the following factors?

(Multiple Choice)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

While the DCF approach often is more theoretically sound than the IRR approach (which can have multiple solutions),IRR is more widely used in LBO analyses since investors often find it more intuitively appealing,that is,the higher an investment's IRR,the better the investment's return relative to its cost The IRR is the discount rate that equates the projected cash flows and terminal value with the initial equity investment.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Kinder Morgan Buyout Raises Ethical Questions

In the largest management buyout in U.S. history at that time, Kinder Morgan Inc.'s management proposed to take the oil and gas pipeline firm private in 2006 in a transaction that valued the firm's outstanding equity at $13.5 billion. Under the proposal, chief executive Richard Kinder and other senior executives would contribute shares valued at $2.8 billion to the newly private company. An additional $4.5 billion would come from private equity investors, including Goldman Sachs Capital partners, American International Group Inc., and the Carlyle Group. Including assumed debt, the transaction was valued at about $22 billion. The transaction also was notable for the governance and ethical issues it raised. Reflecting the struggles within the corporation, the deal did not close until mid-2007.

The top management of Kinder Morgan Inc. waited more than two months before informing the firm's board of its desire to take the company private. It is customary for boards governing firms whose managements are interested in buying out public shareholders to create a committee within the board consisting of independent board members to solicit other bids. While the Kinder Morgan board did eventually create such a committee, the board's lack of awareness of the pending management proposal gave management an important lead over potential bidders in structuring a proposal. By being involved early on in the process, a board has more time to negotiate terms more favorable to shareholders. The transaction also raised questions about the potential conflicts of interest in cases where investment bankers who were hired to advise management and the board on the "fairness" of the offer price also were potential investors in the buyout.

Kinder Morgan's management hired Goldman Sachs in February 2006 to explore "strategic" options for the firm to enhance shareholder value. The leveraged buyout option was proposed by Goldman Sachs on March 7, followed by their proposal to become the primary investor in the LBO on April 5. The management buyout group hired a number of law firms and other investment banks as advisors and discussed the proposed buyout with credit-rating firms to assess how much debt the firm could support without experiencing a downgrade in its credit rating.

On May 13, 2006, the full board was finally made aware of the proposal. The board immediately demanded that a standstill agreement that had been signed by Richard Kinder, CEO and leader of the buyout group, be terminated. The agreement did not permit the firm to talk to any alternative bidders for a period of 90 days. While investment banks and buyout groups often propose such an agreement to ensure that they can perform adequate due diligence, this extended period is not necessarily in the interests of the firm's shareholders because it puts alternative suitors coming in later at a distinct disadvantage. Later bidders simply lack sufficient time to make an adequate assessment of the true value of the target and structure their own proposals. In this way, the standstill agreement could discourage alternative bids for the business.

A special committee of the board was set up to negotiate with the management buyout group, and it was ultimately able to secure a $107.50 per share price for the firm, significantly higher than the initial offer. The discussions were rumored to have been very contentious due to the board's annoyance with the delay in informing them. Reflecting the strong financial performance of the firm and an improving equity market, Kinder Morgan raised $2.4 billion in early 2011 in the largest private equity-backed IPO in history. The majority of the IPO proceeds were paid out to the firm's private equity investors as a dividend.

Berman and Sender, 2006

Financing LBOs--The SunGard Transaction

With their cash hoards accumulating at an unprecedented rate, there was little that buyout firms could do but to invest in larger firms. Consequently, the average size of LBO transactions grew significantly during 2005. In a move reminiscent of the blockbuster buyouts of the late 1980s, seven private investment firms acquired 100 percent of the outstanding stock of SunGard Data Systems Inc. (SunGard) in late 2005. SunGard is a financial software firm known for providing application and transaction software services and creating backup data systems in the event of disaster. The company's software manages 70 percent of the transactions made on the Nasdaq stock exchange, but its biggest business is creating backup data systems in case a client's main systems are disabled by a natural disaster, blackout, or terrorist attack. Its large client base for disaster recovery and back-up systems provides a substantial and predictable cash flow.

SunGard's new owners include Silver lake Partners, Bain Capital LLC, The Blackstone Group L.P., Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., Providence Equity Partners Inc. and Texas Pacific Group. Buyout firms in 2005 tended to band together to spread the risk of a deal this size and to reduce the likelihood of a bidding war. Indeed, with SunGard, there was only one bidder, the investor group consisting of these seven firms.

The software side of SunGard is believed to have significant growth potential, while the disaster-recovery side provides a large stable cash flow. Unlike many LBOs, the deal was announced as being all about growth of the financial services software side of the business. The deal is structured as a merger, since SunGard would be merged into a shell corporation created by the investor group for acquiring SunGard. Going private, allows SunGard to invest heavily in software without being punished by investors, since such investments are expensed and reduce reported earnings per share. Going private also allows the firm to eliminate the burdensome reporting requirements of being a public company.

The buyout represented potentially a significant source of fee income for the investor group. In addition to the 2 percent management fees buyout firms collect from investors in the funds they manage, they receive substantial fee income from each investment they make on behalf of their funds. For example, the buyout firms receive a 1 percent deal completion fee, which is more than $100 million in the SunGard transaction. Buyout firms also receive fees paid for by the target firm that is "going private" for arranging financing. Moreover, there are also fees for conducting due diligence and for monitoring the ongoing performance of the firm taken private. Finally, when the buyout firms exit their investments in the target firm via a sale to a strategic buyer or a secondary IPO, they receive 20 percent (i.e., so-called carry fee) of any profits.

Under the terms of the agreement, SunGard shareholders received $36 per share, a 14 percent premium over the SunGard closing price as of the announcement date of March 28, 2005, and 40 percent more than when the news first leaked about the deal a week earlier. From the SunGard shareholders' perspective, the deal is valued at $11.4 billion dollars consisting of $10.9 billion for outstanding shares and "in-the-money" options (i.e., options whose exercise price is less than the firm's market price per share) plus $500 million in debt on the balance sheet.

The seven equity investors provided $3.5 billion in capital with the remainder of the purchase price financed by commitments from a lending consortium consisting of Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., and Deutsche Bank. The purpose of the loans is to finance the merger, repay or refinance SunGard's existing debt, provide ongoing working capital, and pay fees and expenses incurred in connection with the merger. The total funds necessary to complete the merger and related fees and expenses is approximately $11.3 billion, consisting of approximately $10.9 billion to pay SunGard's stockholders and about $400.7 million to pay fees and expenses related to the merger and the financing arrangements. Note that the fees that are to be financed comprise almost 4 percent of the purchase price. Ongoing working capital needs and capital expenditures required obtaining commitments from lenders well in excess of $11.3 billion.

The merger financing consists of several tiers of debt and "credit facilities." Credit facilities are arrangements for extending credit. The senior secured debt and senior subordinated debt are intended to provide "permanent" or long-term financing. Senior debt covenants included restrictions on new borrowing, investments, sales of assets, mergers and consolidations, prepayments of subordinated indebtedness, capital expenditures, liens and dividends and other distributions, as well as a minimum interest coverage ratio and a maximum total leverage ratio.

If the offering of notes is not completed on or prior to the closing, the banks providing the financing have committed to provide up to $3 billion in loans under a senior subordinated bridge credit facility. The bridge loans are intended as a form of temporary financing to satisfy immediate cash requirements until permanent financing can be arranged. A special purpose SunGard subsidiary will purchase receivables from SunGard, with the purchases financed through the sale of the receivables to the lending consortium. The lenders subsequently finance the purchase of the receivables by issuing commercial paper, which is repaid as the receivables are collected. The special purpose subsidiary is not shown on the SunGard balance sheet. Based on the value of receivables at closing, the subsidiary could provide up to $500 million. The obligation of the lending consortium to buy the receivables will expire on the sixth anniversary of the closing of the merger.

The following table provides SunGard's post-merger proforma capital structure. Note that the proforma capital structure is portrayed as if SunGard uses 100 percent of bank lending commitments. Also, note that individual LBO investors may invest monies from more than one fund they manage. This may be due to the perceived attractiveness of the opportunity or the limited availability of money in any single fund. Of the $9 billion in debt financing, bank loans constitute 56 percent and subordinated or mezzanine debt comprises represents 44 percent.

SunGard Proforma Capital Structure  1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-Explain how the way in which the LBO is financed affects the way it is operated and the timing of when equity investors choose to exit the business.Be specific.

1The roman numeral II refers to the fund providing the equity capital managed by the

partnership.

Case Study Discussion Questions:

-Explain how the way in which the LBO is financed affects the way it is operated and the timing of when equity investors choose to exit the business.Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

Once the LBO has been consummated,the firm's perceived ability to meet its obligations to current debt and preferred stockholders often deteriorates because the firm takes on a substantial amount of new debt.The firm's pre-LBO debt and preferred stock may be revalued in the market by investors to reflect this higher perceived risk,resulting in a significant reduction in the market value of both debt and preferred equity owned by pre-LBO investors.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

The cost of capital method attempts to adjust future cash flows for changes in the cost of capital as the firm reduces its outstanding debt.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (37)

(37)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

Cerberus Capital Management Acquires Chrysler Corporation

According to the terms of the transaction, Cerberus would own 80.1 percent of Chrysler's auto manufacturing and financial services businesses in exchange for $7.4 billion in cash. Daimler would continue to own 19.9 percent of the new business, Chrysler Holdings LLC. Of the $7.4 billion, Daimler would receive $1.35 billion while the remaining $6.05 billion would be invested in Chrysler (i.e., $5.0 billion is to be invested in the auto manufacturing operation and $1.05 billion in the finance unit). Daimler also agreed to pay to Cerberus $1.6 billion to cover Chrysler's long-term debt and cumulative operating losses during the four months between the signing of the merger agreement and the actual closing. In acquiring Chrysler, Cerberus assumed responsibility for an estimated $18 billion in unfunded retiree pension and medical benefits. Daimler also agreed to loan Chrysler Holdings LLC $405 million.

The transaction is atypical of those involving private equity investors, which usually take public firms private, expecting to later sell them for a profit. The private equity firm pays for the acquisition by borrowing against the firm's assets or cash flow. However, the estimated size of Chrysler's retiree health-care liabilities and the uncertainty of future cash flows make borrowing impractical. Therefore, Cerberus agreed to invest its own funds in the business to keep it running while it restructured the business.

By going private, Cerberus would be able to focus on the long-term without the disruption of meeting quarterly earnings reports. Cerberus was counting on paring retiree health-care liabilities through aggressive negotiations with the United Auto Workers (UAW). Cerberus sought a deal similar to what the UAW accepted from Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in late 2006. Under this agreement, the management of $1.2 billion in health-care liabilities was transferred to a fund managed by the UAW, with Goodyear contributing $1 billion in cash and Goodyear stock. By transferring responsibility for these liabilities to the UAW, Chrysler believed that it would be able to cut in half the $30 dollar per hour labor cost advantage enjoyed by Toyota. Cerberus also expected to benefit from melding Chrysler's financial unit with Cerberus's 51 percent ownership stake in GMAC, GM's former auto financing business. By consolidating the two businesses, Cerberus hoped to slash cost by eliminating duplicate jobs, combining overlapping operations such as data centers and field offices, and increasing the number of loans generated by combining back-office operations.

However, the 2008 credit market meltdown, severe recession, and subsequent free fall in auto sales threatened the financial viability of Chrysler, despite an infusion of U.S. government capital, and its leasing operations as well as GMAC. GMAC applied for commercial banking status to be able to borrow directly from the U.S. Federal Reserve. In late 2008, the U.S. Treasury purchased $6 billion in GMAC preferred stock to provide additional capital to the financially ailing firm. To avoid being classified as a bank holding company under direct government supervision, Cerberus reduced its ownership in 2009 to 14.9 percent of voting stock and 33 percent of total equity by distributing equity stakes to its coinvestors in GMAC. By surrendering its controlling interest in GMAC, it is less likely that Cerberus would be able to realize anticipated cost savings by combining the GMAC and Chrysler Financial operations. In early 2009, Chrysler entered into negotiations with Italian auto maker Fiat to gain access to the firm's technology in exchange for a 20 percent stake in Chrysler.

and Answers:

-The new company,Chrysler Holdings,is a limited liability company.Why do you think CCM chose this legal structure over a more conventional corporate structure?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

The primary advantage of the cost of capital method is its relative computational simplicity.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

Case Study Short Essay Examination Questions

"Grave Dancer" Takes Tribune Corporation Private in an Ill-Fated Transaction

At the closing in late December 2007, well-known real estate investor Sam Zell described the takeover of the Tribune Company as "the transaction from hell." His comments were prescient in that what had appeared to be a cleverly crafted, albeit highly leveraged, deal from a tax standpoint was unable to withstand the credit malaise of 2008. The end came swiftly when the 161-year-old Tribune filed for bankruptcy on December 8, 2008.

On April 2, 2007, the Tribune Corporation announced that the firm's publicly traded shares would be acquired in a multistage transaction valued at $8.2 billion. Tribune owned at that time 9 newspapers, 23 television stations, a 25% stake in Comcast's SportsNet Chicago, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team. Publishing accounts for 75% of the firm's total $5.5 billion annual revenue, with the remainder coming from broadcasting and entertainment. Advertising and circulation revenue had fallen by 9% at the firm's three largest newspapers (Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsday in New York) between 2004 and 2006. Despite aggressive efforts to cut costs, Tribune's stock had fallen more than 30% since 2005.

The transaction was implemented in a two-stage transaction, in which Sam Zell acquired a controlling 51% interest in the first stage followed by a backend merger in the second stage in which the remaining outstanding Tribune shares were acquired. In the first stage, Tribune initiated a cash tender offer for 126 million shares (51% of total shares) for $34 per share, totaling $4.2 billion. The tender was financed using $250 million of the $315 million provided by Sam Zell in the form of subordinated debt, plus additional borrowing to cover the balance. Stage 2 was triggered when the deal received regulatory approval. During this stage, an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) bought the rest of the shares at $34 a share (totaling about $4 billion), with Zell providing the remaining $65 million of his pledge. Most of the ESOP's 121 million shares purchased were financed by debt guaranteed by the firm on behalf of the ESOP. At that point, the ESOP held all of the remaining stock outstanding valued at about $4 billion. In exchange for his commitment of funds, Mr. Zell received a 15-year warrant to acquire 40% of the common stock (newly issued) at a price set at $500 million.

Following closing in December 2007, all company contributions to employee pension plans were funneled into the ESOP in the form of Tribune stock. Over time, the ESOP would hold all the stock. Furthermore, Tribune was converted from a C corporation to a Subchapter S corporation, allowing the firm to avoid corporate income taxes. However, it would have to pay taxes on gains resulting from the sale of assets held less than ten years after the conversion from a C to an S corporation (Figure 13.4).  Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-Is this transaction best characterized as a merger,acquisition,leveraged buyout,or spin-off? Explain your

answer.

Tribune deal structure.

The purchase of Tribune's stock was financed almost entirely with debt, with Zell's equity contribution amounting to less than 4% of the purchase price. The transaction resulted in Tribune being burdened with $13 billion in debt (including the approximate $5 billion currently owed by Tribune). At this level, the firm's debt was ten times EBITDA, more than two and a half times that of the average media company. Annual interest and principal repayments reached $800 million (almost three times their preacquisition level), about 62% of the firm's previous EBITDA cash flow of $1.3 billion. While the ESOP owned the company, it was not be liable for the debt guaranteed by Tribune.

The conversion of Tribune into a Subchapter S corporation eliminated the firm's current annual tax liability of $348 million. Such entities pay no corporate income tax but must pay all profit directly to shareholders, who then pay taxes on these distributions. Since the ESOP was the sole shareholder, Tribune was expected to be largely tax exempt, since ESOPs are not taxed.

In an effort to reduce the firm's debt burden, the Tribune Company announced in early 2008 the formation of a partnership in which Cablevision Systems Corporation would own 97% of Newsday for $650 million, with Tribune owning the remaining 3%. However, Tribune was unable to sell the Chicago Cubs (which had been expected to fetch as much as $1 billion) and the minority interest in SportsNet Chicago to help reduce the debt amid the 2008 credit crisis. The worsening of the recession, accelerated by the decline in newspaper and TV advertising revenue, as well as newspaper circulation, thereby eroded the firm's ability to meet its debt obligations.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the Tribune Company sought a reprieve from its creditors while it attempted to restructure its business. Although the extent of the losses to employees, creditors, and other stakeholders is difficult to determine, some things are clear. Any pension funds set aside prior to the closing remain with the employees, but it is likely that equity contributions made to the ESOP on behalf of the employees since the closing would be lost. The employees would become general creditors of Tribune. As a holder of subordinated debt, Mr. Zell had priority over the employees if the firm was liquidated and the proceeds distributed to the creditors.

Those benefitting from the deal included Tribune's public shareholders, including the Chandler family, which owed 12% of Tribune as a result of its prior sale of the Times Mirror to Tribune, and Dennis FitzSimons, the firm's former CEO, who received $17.7 million in severance and $23.8 million for his holdings of Tribune shares. Citigroup and Merrill Lynch received $35.8 million and $37 million, respectively, in advisory fees. Morgan Stanley received $7.5 million for writing a fairness opinion letter. Finally, Valuation Research Corporation received $1 million for providing a solvency opinion indicating that Tribune could satisfy its loan covenants.

What appeared to be one of the most complex deals of 2007, designed to reap huge tax advantages, soon became a victim of the downward-spiraling economy, the credit crunch, and its own leverage. A lawsuit filed in late 2008 on behalf of Tribune employees contended that the transaction was flawed from the outset and intended to benefit Sam Zell and his advisors and Tribune's board. Even if the employees win, they will simply have to stand in line with other Tribune creditors awaiting the resolution of the bankruptcy court proceedings.

:

-Is this transaction best characterized as a merger,acquisition,leveraged buyout,or spin-off? Explain your

answer.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

Showing 61 - 80 of 98

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)