Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

The tax status of the transaction may influence the purchase price by

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (41)

(41)

Tax-free reorganizations generally require that all or substantially all of the target company's assets or shares be acquired.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

Archer Daniel Midland (ADM) wants to acquire AgriCorp to augment its ethanol manufacturing capability. AgriCorp wants

the transaction to be tax-free for its shareholders. ADM wants to preserve AgriCorp's significant investment tax credits and tax loss carryforwards so that they transfer in the transaction. Also, ADM plans on selling certain unwanted AgriCorp assets to help finance the transaction. How would you structure the deal so that both parties' objectives could be achieved?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (23)

(23)

Johnson & Johnson Uses Financial Engineering to Acquire Synthes Corporation

While tax considerations rarely are the primary motivation for takeovers, they make transactions more attractive.

Tax considerations may impact where and when investments such as M&As are made.

Foreign cash balances give multinational corporations flexibility in financing M&As.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

United States–based Johnson & Johnson (J&J), the world’s largest healthcare products company, employed creative tax strategies in undertaking the biggest takeover in its history. When J&J first announced that it would acquire Swiss medical device maker Synthes for $19.7 million in stock and cash, the firm indicated that the deal would dilute its current shareholders due to the issuance of 204 million new shares. Investors expressed their dismay by pushing the firm’s share price down immediately following the announcement. J&J looked for a way to make the deal more attractive to investors while preserving the composition of the purchase price paid to Synthes’ shareholders (two-thirds stock and the remainder in cash). They could defer the payment of taxes on that portion of the purchase price received in J&J shares until such shares were sold; however, they would incur an immediate tax liability on any cash received.

Having found a loophole in the IRS’s guidelines for utilizing funds held in foreign subsidiaries, J&J was able to make the deal’s financing structure accretive to earnings following closing. In 2011, the IRS had ruled that cash held in foreign operations repatriated to the United States would be considered a dividend paid by the subsidiary to the parent, subject to the appropriate tax rate. Because the United States has the highest corporate tax rate among developed countries, U.S. multinational firms have an incentive to reinvest earnings of their foreign subsidiaries abroad.

With this in mind, J&J used the foreign earnings held by its Irish subsidiary to buy 204 million of its own shares, valued at $12.9 billion, held by Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, which had previously acquired J&J shares in the open market. The buyback of J&J shares held by these investment banks increased the consolidated firm’s earnings per share. These shares, along with cash, were exchanged for outstanding Synthes’ shares to fund the transaction. J&J also avoided a hefty tax payment by not repatriating these earnings to the United States, where they would have been taxed at a 35% corporate rate rather than the 12% rate in Ireland. Investors reacted favorably, boosting J&J’s share price by more than 2% in mid-2012, when the firm announced the deal would be accretive rather than dilutive. Presumably, the IRS will move to prevent future deals from being financed in a similar manner.

Merck and Schering-Plough Merger: When Form Overrides Substance

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it really a duck? That is a question Johnson & Johnson might ask about a 2009 transaction involving pharmaceutical companies Merck and Schering-Plough. On August 7, 2009, shareholders of Merck and Company (“Merck”) and Schering-Plough Corp. (Schering-Plough) voted overwhelmingly to approve a $41.1 billion merger of the two firms. With annual revenues of $42.4 billion, the new Merck will be second in size only to global pharmaceutical powerhouse Pfizer Inc.

At closing on November 3, 2009, Schering-Plough shareholders received $10.50 and 0.5767 of a share of the common stock of the combined company for each share of Schering-Plough stock they held, and Merck shareholders received one share of common stock of the combined company for each share of Merck they held. Merck shareholders voted to approve the merger agreement, and Schering-Plough shareholders voted to approve both the merger agreement and the issuance of shares of common stock in the combined firms. Immediately after the merger, the former shareholders of Merck and Schering-Plough owned approximately 68 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of the shares of the combined companies.

The motivation for the merger reflects the potential for $3.5 billion in pretax annual cost savings, with Merck reducing its workforce by about 15 percent through facility consolidations, a highly complementary product offering, and the substantial number of new drugs under development at Schering-Plough. Furthermore, the deal increases Merck’s international presence, since 70 percent of Schering-Plough’s revenues come from abroad. The combined firms both focus on biologics (i.e., drugs derived from living organisms). The new firm has a product offering that is much more diversified than either firm had separately.

The deal structure involved a reverse merger, which allowed for a tax-free exchange of shares and for Schering-Plough to argue that it was the acquirer in this transaction. The importance of the latter point is explained in the following section.

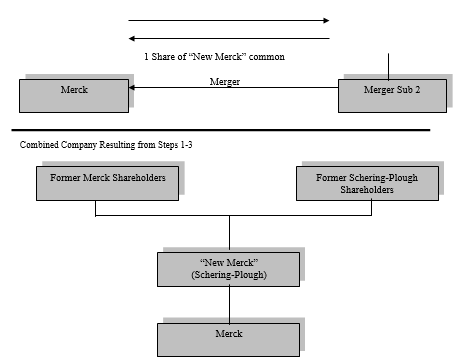

To implement the transaction, Schering-Plough created two merger subsidiaries (i.e., Merger Subs 1 and 2) and moved $10 billion in cash provided by Merck and 1.5 billion new shares (i.e., so-called “New Merck” shares approved by Schering-Plough shareholders) in the combined Schering-Plough and Merck companies into the subsidiaries. Merger Sub 1 was merged into Schering-Plough, with Schering-Plough the surviving firm. Merger Sub 2 was merged with Merck, with Merck surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Schering-Plough. The end result is the appearance that Schering-Plough (renamed Merck) acquired Merck through its wholly-owned subsidiary (Merger Sub 2). In reality, Merck acquired Schering-Plough.

Former shareholders of Schering-Plough and Merck become shareholders in the new Merck. The “New Merck” is simply Schering-Plough renamed Merck. This structure allows Schering-Plough to argue that no change in control occurred and that a termination clause in a partnership agreement with Johnson & Johnson should not be triggered. Under the agreement, J&J has the exclusive right to sell a rheumatoid arthritis drug it had developed called Remicade, and Schering-Plough has the exclusive right to sell the drug outside the United States, reflecting its stronger international distribution channel. If the change of control clause were triggered, rights to distribute the drug outside the United States would revert back to J&J. Remicade represented $2.1 billion or about 20 percent of Schering-Plough’s 2008 revenues and about 70 percent of the firm’s international revenues. Consequently, retaining these revenues following the merger was important to both Merck and Schering-Plough.

The multi-step process for implementing this transaction is illustrated in the following diagrams. From a legal perspective, all these actions occur concurrently.

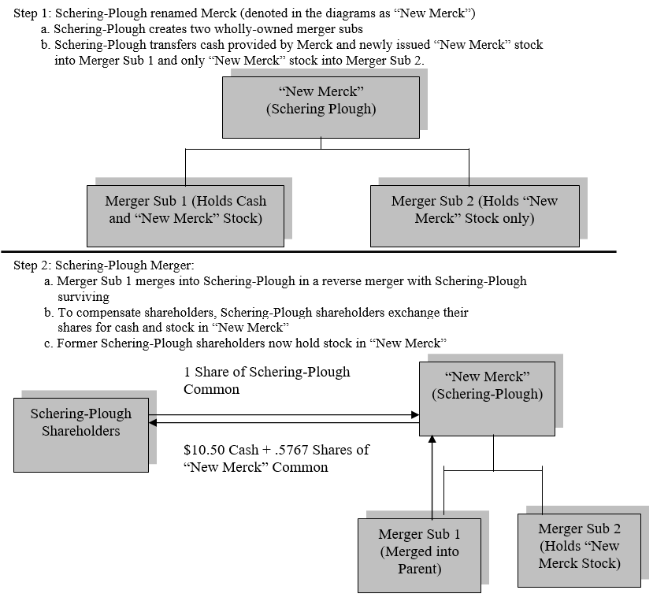

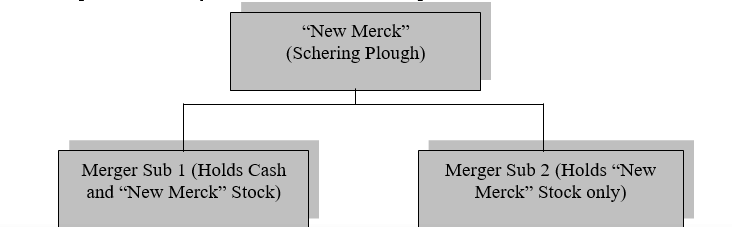

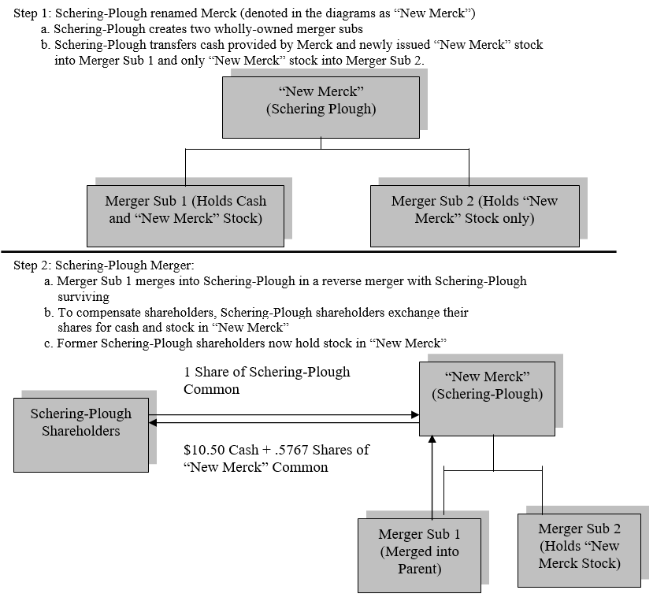

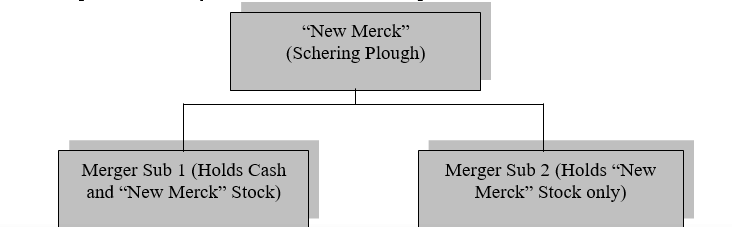

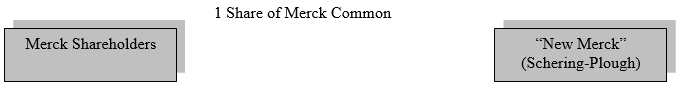

Step 1: Schering-Plough renamed Merck (denoted in the diagrams as "New Merck")

a. Schering-Plough creates two wholly-owned merger subs

b. Schering-Plough transfers cash provided by Merck and newly issued "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 1 and only "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 2.

Step 1: Schering-Plough renamed Merck (denoted in the diagrams as "New Merck")

a. Schering-Plough creates two wholly-owned merger subs

b. Schering-Plough transfers cash provided by Merck and newly issued "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 1 and only "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 2.

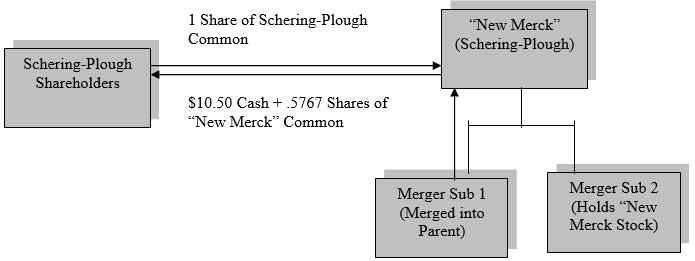

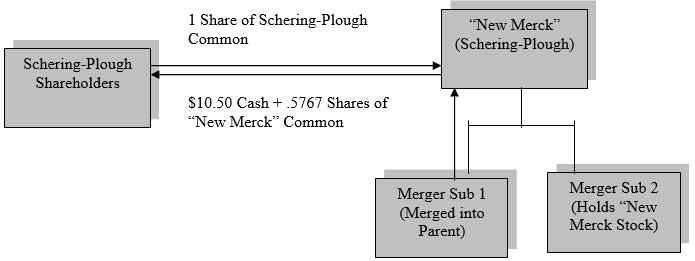

Step 2: Schering-Plough Merger:

a. Merger Sub 1 merges into Schering-Plough in a reverse merger with Schering-Plough surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Schering-Plough shareholders exchange their shares for cash and stock in "New Merck"

c. Former Schering-Plough shareholders now hold stock in "New Merck"

Step 2: Schering-Plough Merger:

a. Merger Sub 1 merges into Schering-Plough in a reverse merger with Schering-Plough surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Schering-Plough shareholders exchange their shares for cash and stock in "New Merck"

c. Former Schering-Plough shareholders now hold stock in "New Merck"

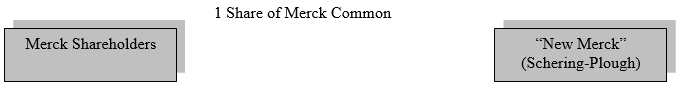

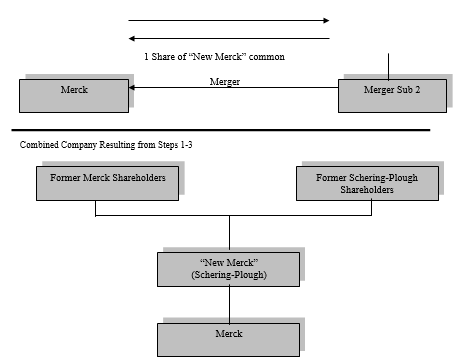

Step 3: Merck Merger:

a. Merger Sub 2 merges into Merck with Merck surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Merck shareholders exchange their shares for shares in "New Merck"

c. Former shareholders in Merck now hold shares in "New Merck" (i.e., a renamed Schering-Plough)

d, Merger Sub 2, a subsidiary of "New Merck," now owns Merck.

Step 3: Merck Merger:

a. Merger Sub 2 merges into Merck with Merck surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Merck shareholders exchange their shares for shares in "New Merck"

c. Former shareholders in Merck now hold shares in "New Merck" (i.e., a renamed Schering-Plough)

d, Merger Sub 2, a subsidiary of "New Merck," now owns Merck.

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck’s chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm’s board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough’s board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How did the use of a reverse merger facilitate the transaction?

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck’s chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm’s board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough’s board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How did the use of a reverse merger facilitate the transaction?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (39)

(39)

Consolidation in the Wireless Communications Industry:

Vodafone Acquires AirTouch

.

Deregulation of the telecommunications industry has resulted in increased consolidation. In Europe, rising competition is the catalyst driving mergers. In the United States, the break up of AT&T in the mid-1980s and the subsequent deregulation of the industry has led to key alliances, JVs, and mergers, which have created cellular powerhouses capable of providing nationwide coverage. Such coverage is being achieved by roaming agreements between carriers and acquisitions by other carriers. Although competition has been heightened as a result of deregulation, the telecommunications industry continues to be characterized by substantial barriers to entry. These include the requirement to obtain licenses and the need for an extensive network infrastructure. Wireless communications continue to grow largely at the expense of traditional landline services as cellular service pricing continues to decrease. Although the market is likely to continue to grow rapidly, success is expected to go to those with the financial muscle to satisfy increasingly sophisticated customer demands. What follows is a brief discussion of the motivations for the merger between Vodafone and AirTouch Communications. This discussion includes a description of the key elements of the deal structure that made the Vodafone offer more attractive than a competing offer from Bell Atlantic.

Vodafone

Company History

Vodafone is a wireless communications company based in the United Kingdom. The company is located in 13 countries in Europe, Africa, and Australia/New Zealand. Vodafone reaches more than 9.5 million subscribers. It has been the market leader in the United Kingdom since 1986 and as of 1998 had more than 5 million subscribers in the United Kingdom alone. The company has been very successful at marketing and selling prepaid services in Europe. Vodafone also is involved in a venture called Globalstar, LP, a limited partnership with Loral Space and Communications and Qualcomm, a phone manufacturer. "Globalstar will construct and operate a worldwide, satellite-based communications system offering global mobile voice, fax, and data communications in over 115 countries, covering over 85% of the world's population".

Strategic Intent

Vodafone's focus is on global expansion. They are expanding through partnerships and by purchasing licenses. Notably, Vodafone lacked a significant presence in the United States, the largest mobile phone market in the world. For Vodafone to be considered a truly global company, the firm needed a presence in the Unites States. Vodafone's strategy is focused on maintaining high growth levels in its markets and increasing profitability; maintaining their current customer base; accelerating innovation; and increasing their global presence through acquisitions, partnerships, or purchases of new licenses. Vodafone's current strategy calls for it to merge with a company with substantial market share in the United States and Asia, which would fill several holes in Vodafone's current geographic coverage.

Company Structure

The company is very decentralized. The responsibilities of the corporate headquarters in the United Kingdom lie in developing corporate strategic direction, compiling financial information, reporting and developing relationships with the various stock markets, and evaluating new expansion opportunities. The management of operations is left to the countries' management, assuming business plans and financial measures are being met. They have a relatively flat management structure. All of their employees are shareowners in the company. They have very low levels of employee turnover, and the workforce averages 33 years of age.

AirTouch

Company History

AirTouch Communications launched it first cellular service network in 1984 in Los Angeles during the opening ceremonies at the 1984 Olympics. The original company was run under the name PacTel Cellular, a subsidiary of Pacific Telesis. In 1994, PacTel Cellular spun off from Pacific Telesis and became AirTouch Communications, under the direction of Chair and Chief Executive Officer Sam Ginn. Ginn believed that the most exciting growth potential in telecommunications is in the wireless and not the landline services segment of the industry. In 1998, AirTouch operated in 13 countries on three continents, serving more than 12 million customers, as a worldwide carrier of cellular services, personal communication services (PCS), and paging services. AirTouch has chosen to compete on a global front through various partnerships and JVs. Recognizing the massive growth potential outside the United States, AirTouch began their global strategy immediately after the spin-off.

Strategic Intent

AirTouch has chosen to differentiate itself in its domestic regions based on the concept of "Superior Service Delivery." The company's focus is on being available to its customers 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and on delivering pricing options that meet the customer's needs. AirTouch allows customers to change pricing plans without penalty. The company also emphasizes call clarity and quality and extensive geographic coverage. The key challenges AirTouch faces on a global front is in reducing churn (i.e., the percentage of customers leaving), implementing improved digital technology, managing pressure on service pricing, and maintaining profit margins by focusing on cost reduction. Other challenges include creating a domestic national presence.

Company Structure

AirTouch is decentralized. Regions have been developed in the U.S. market and are run autonomously with respect to pricing decisions, marketing campaigns, and customer care operations. Each region is run as a profit center. Its European operations also are run independently from each other to be able to respond to the competitive issues unique to the specific countries. All employees are shareowners in the company, and the average age of the workforce is in the low to mid-30s. Both companies are comparable in terms of size and exhibit operating profit margins in the mid-to-high teens. AirTouch has substantially less leverage than Vodafone.

Merger Highlights

Vodafone began exploratory talks with AirTouch as early as 1996 on a variety of options ranging from partnerships to a merger. Merger talks continued informally until late 1998 when they were formally broken off. Bell Atlantic, interested in expanding its own mobile phone business's geographic coverage, immediately jumped into the void by proposing to AirTouch that together they form a new wireless company. In early 1999, Vodafone once again entered the fray, sparking a sharp takeover battle for AirTouch. Vodafone emerged victorious by mid-1999.

Motivation for the Merger

Shared Vision

The merger would create a more competitive, global wireless telecommunications company than either company could achieve separately. Moreover, both firms shared the same vision of the telecommunications industry. Mobile telecommunications is believed to be the among the fastest-growing segment of the telecommunications industry, and over time mobile voice will replace large amounts of telecommunications traffic carried by fixed-line networks and will serve as a major platform for voice and data communication. Both companies believe that mobile penetration will reach 50% in developed countries by 2003 and 55% and 65% in the United States and developed European countries, respectively, by 2005.

Complementary Assets

Scale, operating strength, and complementary assets were given as compelling reasons for the merger. The combination of AirTouch and Vodafone would create the largest mobile telecommunication company at the time, with significant presence in the United Kingdom, United States, continental Europe, and Asian Pacific region. The scale and scope of the operations is expected to make the combined firms the vendor of choice for business travelers and international corporations. Interests in operations in many countries will make Vodafone AirTouch more attractive as a partner for other international fixed and mobile telecommunications providers. The combined scale of the companies also is expected to enhance its ability to develop existing networks and to be in the forefront of providing technologically advanced products and services.

Synergy

Anticipated synergies include after-tax cost savings of $340 million annually by the fiscal year ending March 31, 2002. The estimated net present value of these synergies is $3.6 billion discounted at 9%. The cost savings arise from global purchasing and operating efficiencies, including volume discounts, lower leased line costs, more efficient voice and data networks, savings in development and purchase of third-generation mobile handsets, infrastructure, and software. Revenues should be enhanced through the provision of more international coverage and through the bundling of services for corporate customers that operate as multinational businesses and business travelers.

AirTouch's Board Analyzes Options

Morgan Stanley, AirTouch's investment banker, provided analyses of the current prices of the Vodafone and Bell Atlantic stocks, their historical trading ranges, and the anticipated trading prices of both companies' stock on completion of the merger and on redistribution of the stock to the general public. Both offers were structured so as to constitute essentially tax-free reorganizations. The Vodafone proposal would qualify as a Type A reorganization under the Internal Revenue Service Code; hence, it would be tax-free, except for the cash portion of the offer, for U.S. holders of AirTouch common and holders of preferred who converted their shares before the merger. The Bell Atlantic offer would qualify as a Type B tax-free reorganization. Table 1 highlights the primary characteristics of the form of payment (total consideration) of the two competing offers.

Table 1. Camparis an of Farm of PaymentTotal Consideration Vodafone Bell Atlantic 5 shares of Vodafone common plus \ 9 for each 1.54 shares of Bell Atlantic for each share of AirTouch common share of AirTouch common subject to the transaction being treated as a pooling of interest under U.S. GAAP. Share exchange ratio adjusted upward 9 months out to reflect the payment of dividends on the Bell Atlantic stock. A share exchange ratio collar would be used to ensure that Air Touch shareholders would receive shares valued at \ 80.08 . If the average closing price of Bell Atlantic stock were less than \ 48 , the exchange ratio would be increased to 1.6683 . If the price exceeded \ 52 the exchange rate would remain at 1.54.

The collar guarantees the price of Bell Atlantic stock for the Air Touch shareholders because and both equal . Morgan Stanley's primary conclusions were as follows:

Morgan Stanley’s primary conclusions were as follows:

1. Bell Atlantic had a current market value of $83 per share of AirTouch stock based on the $53.81 closing price of Bell Atlantic common stock on January 14, 1999. The collar would maintain the price at $80.08 per share if the price of Bell Atlantic stock during a specified period before closing were between $48 and $52 per share.

2. The Vodafone proposal had a current market value of $97 per share of AirTouch stock based on Vodafone’s ordinary shares (i.e., common) on January 17, 1999.

3. Following the merger, the market value of the Vodafone American Depository Shares (ADSs) to be received by AirTouch shareholders under the Vodafone proposal could decrease.

4. Following the merger, the market value of Bell Atlantic’s stock also could decrease, particularly in light of the expectation that the proposed transaction would dilute Bell Atlantic’s EPS by more than 10% through 2002.

In addition to Vodafone’s higher value, the board tended to favor the Vodafone offer because it involved less regulatory uncertainty. As U.S. corporations, a merger between AirTouch and Bell Atlantic was likely to receive substantial scrutiny from the U.S. Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, and the FCC. Moreover, although both proposals could be completed tax-free, except for the small cash component of the Vodafone offer, the Vodafone offer was not subject to achieving any specific accounting treatment such as pooling of interests under U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

Recognizing their fiduciary responsibility to review all legitimate offers in a balanced manner, the AirTouch board also considered a number of factors that made the Vodafone proposal less attractive. The failure to do so would no doubt trigger shareholder lawsuits. The major factors that detracted from the Vodafone proposal were that it would not result in a national presence in the United States, the higher volatility of its stock, and the additional debt Vodafone would have to assume to pay the cash portion of the purchase price. Despite these concerns, the higher offer price from Vodafone (i.e., $97 to $83) won the day.

Acquisition Vehicle and Post Closing Organization

In the merger, AirTouch became a wholly owned subsidiary of Vodafone. Vodafone issued common shares valued at $52.4 billion based on the closing Vodafone ADS on April 20, 1999. In addition, Vodafone paid AirTouch shareholders $5.5 billion in cash. On completion of the merger, Vodafone changed its name to Vodafone AirTouch Public Limited Company. Vodafone created a wholly owned subsidiary, Appollo Merger Incorporated, as the acquisition vehicle. Using a reverse triangular merger, Appollo was merged into AirTouch. AirTouch constituted the surviving legal entity. AirTouch shareholders received Vodafone voting stock and cash for their AirTouch shares. Both the AirTouch and Appollo shares were canceled. After the merger, AirTouch shareholders owned slightly less than 50% of the equity of the new company, Vodafone AirTouch. By using the reverse merger to convey ownership of the AirTouch shares, Vodafone was able to ensure that all FCC licenses and AirTouch franchise rights were conveyed legally to Vodafone. However, Vodafone was unable to avoid seeking shareholder approval using this method. Vodafone ADS’s traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). Because the amount of new shares being issued exceeded 20% of Vodafone’s outstanding voting stock, the NYSE required that Vodafone solicit its shareholders for approval of the proposed merger.

Following this transaction, the highly aggressive Vodafone went on to consummate the largest merger in history in 2000 by combining with Germany’s telecommunications powerhouse, Mannesmann, for $180 billion. Including assumed debt, the total purchase price paid by Vodafone AirTouch for Mannesmann soared to $198 billion. Vodafone AirTouch was well on its way to establishing itself as a global cellular phone powerhouse.

-How valid are the reasons for the proposed merger?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (43)

(43)

Which of the following is not considered a tax-free reorganization?

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (43)

(43)

Johnson & Johnson Uses Financial Engineering to Acquire Synthes Corporation

While tax considerations rarely are the primary motivation for takeovers, they make transactions more attractive.

Tax considerations may impact where and when investments such as M&As are made.

Foreign cash balances give multinational corporations flexibility in financing M&As.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

United States–based Johnson & Johnson (J&J), the world’s largest healthcare products company, employed creative tax strategies in undertaking the biggest takeover in its history. When J&J first announced that it would acquire Swiss medical device maker Synthes for $19.7 million in stock and cash, the firm indicated that the deal would dilute its current shareholders due to the issuance of 204 million new shares. Investors expressed their dismay by pushing the firm’s share price down immediately following the announcement. J&J looked for a way to make the deal more attractive to investors while preserving the composition of the purchase price paid to Synthes’ shareholders (two-thirds stock and the remainder in cash). They could defer the payment of taxes on that portion of the purchase price received in J&J shares until such shares were sold; however, they would incur an immediate tax liability on any cash received.

Having found a loophole in the IRS’s guidelines for utilizing funds held in foreign subsidiaries, J&J was able to make the deal’s financing structure accretive to earnings following closing. In 2011, the IRS had ruled that cash held in foreign operations repatriated to the United States would be considered a dividend paid by the subsidiary to the parent, subject to the appropriate tax rate. Because the United States has the highest corporate tax rate among developed countries, U.S. multinational firms have an incentive to reinvest earnings of their foreign subsidiaries abroad.

With this in mind, J&J used the foreign earnings held by its Irish subsidiary to buy 204 million of its own shares, valued at $12.9 billion, held by Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, which had previously acquired J&J shares in the open market. The buyback of J&J shares held by these investment banks increased the consolidated firm’s earnings per share. These shares, along with cash, were exchanged for outstanding Synthes’ shares to fund the transaction. J&J also avoided a hefty tax payment by not repatriating these earnings to the United States, where they would have been taxed at a 35% corporate rate rather than the 12% rate in Ireland. Investors reacted favorably, boosting J&J’s share price by more than 2% in mid-2012, when the firm announced the deal would be accretive rather than dilutive. Presumably, the IRS will move to prevent future deals from being financed in a similar manner.

Merck and Schering-Plough Merger: When Form Overrides Substance

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it really a duck? That is a question Johnson & Johnson might ask about a 2009 transaction involving pharmaceutical companies Merck and Schering-Plough. On August 7, 2009, shareholders of Merck and Company (“Merck”) and Schering-Plough Corp. (Schering-Plough) voted overwhelmingly to approve a $41.1 billion merger of the two firms. With annual revenues of $42.4 billion, the new Merck will be second in size only to global pharmaceutical powerhouse Pfizer Inc.

At closing on November 3, 2009, Schering-Plough shareholders received $10.50 and 0.5767 of a share of the common stock of the combined company for each share of Schering-Plough stock they held, and Merck shareholders received one share of common stock of the combined company for each share of Merck they held. Merck shareholders voted to approve the merger agreement, and Schering-Plough shareholders voted to approve both the merger agreement and the issuance of shares of common stock in the combined firms. Immediately after the merger, the former shareholders of Merck and Schering-Plough owned approximately 68 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of the shares of the combined companies.

The motivation for the merger reflects the potential for $3.5 billion in pretax annual cost savings, with Merck reducing its workforce by about 15 percent through facility consolidations, a highly complementary product offering, and the substantial number of new drugs under development at Schering-Plough. Furthermore, the deal increases Merck’s international presence, since 70 percent of Schering-Plough’s revenues come from abroad. The combined firms both focus on biologics (i.e., drugs derived from living organisms). The new firm has a product offering that is much more diversified than either firm had separately.

The deal structure involved a reverse merger, which allowed for a tax-free exchange of shares and for Schering-Plough to argue that it was the acquirer in this transaction. The importance of the latter point is explained in the following section.

To implement the transaction, Schering-Plough created two merger subsidiaries (i.e., Merger Subs 1 and 2) and moved $10 billion in cash provided by Merck and 1.5 billion new shares (i.e., so-called “New Merck” shares approved by Schering-Plough shareholders) in the combined Schering-Plough and Merck companies into the subsidiaries. Merger Sub 1 was merged into Schering-Plough, with Schering-Plough the surviving firm. Merger Sub 2 was merged with Merck, with Merck surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Schering-Plough. The end result is the appearance that Schering-Plough (renamed Merck) acquired Merck through its wholly-owned subsidiary (Merger Sub 2). In reality, Merck acquired Schering-Plough.

Former shareholders of Schering-Plough and Merck become shareholders in the new Merck. The “New Merck” is simply Schering-Plough renamed Merck. This structure allows Schering-Plough to argue that no change in control occurred and that a termination clause in a partnership agreement with Johnson & Johnson should not be triggered. Under the agreement, J&J has the exclusive right to sell a rheumatoid arthritis drug it had developed called Remicade, and Schering-Plough has the exclusive right to sell the drug outside the United States, reflecting its stronger international distribution channel. If the change of control clause were triggered, rights to distribute the drug outside the United States would revert back to J&J. Remicade represented $2.1 billion or about 20 percent of Schering-Plough’s 2008 revenues and about 70 percent of the firm’s international revenues. Consequently, retaining these revenues following the merger was important to both Merck and Schering-Plough.

The multi-step process for implementing this transaction is illustrated in the following diagrams. From a legal perspective, all these actions occur concurrently.

Step 1: Schering-Plough renamed Merck (denoted in the diagrams as "New Merck")

a. Schering-Plough creates two wholly-owned merger subs

b. Schering-Plough transfers cash provided by Merck and newly issued "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 1 and only "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 2.

Step 1: Schering-Plough renamed Merck (denoted in the diagrams as "New Merck")

a. Schering-Plough creates two wholly-owned merger subs

b. Schering-Plough transfers cash provided by Merck and newly issued "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 1 and only "New Merck" stock into Merger Sub 2.

Step 2: Schering-Plough Merger:

a. Merger Sub 1 merges into Schering-Plough in a reverse merger with Schering-Plough surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Schering-Plough shareholders exchange their shares for cash and stock in "New Merck"

c. Former Schering-Plough shareholders now hold stock in "New Merck"

Step 2: Schering-Plough Merger:

a. Merger Sub 1 merges into Schering-Plough in a reverse merger with Schering-Plough surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Schering-Plough shareholders exchange their shares for cash and stock in "New Merck"

c. Former Schering-Plough shareholders now hold stock in "New Merck"

Step 3: Merck Merger:

a. Merger Sub 2 merges into Merck with Merck surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Merck shareholders exchange their shares for shares in "New Merck"

c. Former shareholders in Merck now hold shares in "New Merck" (i.e., a renamed Schering-Plough)

d, Merger Sub 2, a subsidiary of "New Merck," now owns Merck.

Step 3: Merck Merger:

a. Merger Sub 2 merges into Merck with Merck surviving

b. To compensate shareholders, Merck shareholders exchange their shares for shares in "New Merck"

c. Former shareholders in Merck now hold shares in "New Merck" (i.e., a renamed Schering-Plough)

d, Merger Sub 2, a subsidiary of "New Merck," now owns Merck.

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck’s chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm’s board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough’s board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How might allowing the form of a transaction to override the actual spirit or intent of the deal impact the cost of doing business for the parties involved in the distribution agreement? Be specific.

In reality, Merck was the acquirer. Merck provided the money to purchase Schering-Plough, and Richard Clark, Merck’s chairman and CEO, will run the newly combined firm when Fred Hassan, Schering-Plough’s CEO, steps down. The new firm has been renamed Merck to reflect its broader brand recognition. Three-fourths of the new firm’s board consists of former Merck directors, with the remainder coming from Schering-Plough’s board. These factors would give Merck effective control of the combined Merck and Schering-Plough operations. Finally, former Merck shareholders own almost 70 percent of the outstanding shares of the combined companies.

J&J initiated legal action in August 2009, arguing that the transaction was a conventional merger and, as such, triggered the change of control provision in its partnership agreement with Schering-Plough. Schering-Plough argued that the reverse merger bypasses the change of control clause in the agreement, and, consequently, J&J could not terminate the joint venture. In the past, U.S. courts have tended to focus on the form rather than the spirit of a transaction. The implications of the form of a transaction are usually relatively explicit, while determining what was actually intended (i.e., the spirit) in a deal is often more subjective.

In late 2010, an arbitration panel consisting of former federal judges indicated that a final ruling would be forthcoming in 2011. Potential outcomes could include J&J receiving rights to Remicade with damages to be paid by Merck; a finding that the merger did not constitute a change in control, which would keep the distribution agreement in force; or a ruling allowing Merck to continue to sell Remicade overseas but providing for more royalties to J&J.

-How might allowing the form of a transaction to override the actual spirit or intent of the deal impact the cost of doing business for the parties involved in the distribution agreement? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.7/5  (33)

(33)

The tax-free structure is generally not suitable for the acquisition of a division within a corporation.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (32)

(32)

The sale of stock, rather than assets, is generally preferable to the target firm shareholders to avoid double taxation, if the target firm is structured as a limited liability company.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

Under purchase accounting, the difference between the combined firm's shareholders' equity immediately following closing and the acquiring firm's shareholders' equity equals the purchase price paid for the target firm.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (44)

(44)

Consolidation in the Wireless Communications Industry:

Vodafone Acquires AirTouch

.

Deregulation of the telecommunications industry has resulted in increased consolidation. In Europe, rising competition is the catalyst driving mergers. In the United States, the break up of AT&T in the mid-1980s and the subsequent deregulation of the industry has led to key alliances, JVs, and mergers, which have created cellular powerhouses capable of providing nationwide coverage. Such coverage is being achieved by roaming agreements between carriers and acquisitions by other carriers. Although competition has been heightened as a result of deregulation, the telecommunications industry continues to be characterized by substantial barriers to entry. These include the requirement to obtain licenses and the need for an extensive network infrastructure. Wireless communications continue to grow largely at the expense of traditional landline services as cellular service pricing continues to decrease. Although the market is likely to continue to grow rapidly, success is expected to go to those with the financial muscle to satisfy increasingly sophisticated customer demands. What follows is a brief discussion of the motivations for the merger between Vodafone and AirTouch Communications. This discussion includes a description of the key elements of the deal structure that made the Vodafone offer more attractive than a competing offer from Bell Atlantic.

Vodafone

Company History

Vodafone is a wireless communications company based in the United Kingdom. The company is located in 13 countries in Europe, Africa, and Australia/New Zealand. Vodafone reaches more than 9.5 million subscribers. It has been the market leader in the United Kingdom since 1986 and as of 1998 had more than 5 million subscribers in the United Kingdom alone. The company has been very successful at marketing and selling prepaid services in Europe. Vodafone also is involved in a venture called Globalstar, LP, a limited partnership with Loral Space and Communications and Qualcomm, a phone manufacturer. "Globalstar will construct and operate a worldwide, satellite-based communications system offering global mobile voice, fax, and data communications in over 115 countries, covering over 85% of the world's population".

Strategic Intent

Vodafone's focus is on global expansion. They are expanding through partnerships and by purchasing licenses. Notably, Vodafone lacked a significant presence in the United States, the largest mobile phone market in the world. For Vodafone to be considered a truly global company, the firm needed a presence in the Unites States. Vodafone's strategy is focused on maintaining high growth levels in its markets and increasing profitability; maintaining their current customer base; accelerating innovation; and increasing their global presence through acquisitions, partnerships, or purchases of new licenses. Vodafone's current strategy calls for it to merge with a company with substantial market share in the United States and Asia, which would fill several holes in Vodafone's current geographic coverage.

Company Structure

The company is very decentralized. The responsibilities of the corporate headquarters in the United Kingdom lie in developing corporate strategic direction, compiling financial information, reporting and developing relationships with the various stock markets, and evaluating new expansion opportunities. The management of operations is left to the countries' management, assuming business plans and financial measures are being met. They have a relatively flat management structure. All of their employees are shareowners in the company. They have very low levels of employee turnover, and the workforce averages 33 years of age.

AirTouch

Company History

AirTouch Communications launched it first cellular service network in 1984 in Los Angeles during the opening ceremonies at the 1984 Olympics. The original company was run under the name PacTel Cellular, a subsidiary of Pacific Telesis. In 1994, PacTel Cellular spun off from Pacific Telesis and became AirTouch Communications, under the direction of Chair and Chief Executive Officer Sam Ginn. Ginn believed that the most exciting growth potential in telecommunications is in the wireless and not the landline services segment of the industry. In 1998, AirTouch operated in 13 countries on three continents, serving more than 12 million customers, as a worldwide carrier of cellular services, personal communication services (PCS), and paging services. AirTouch has chosen to compete on a global front through various partnerships and JVs. Recognizing the massive growth potential outside the United States, AirTouch began their global strategy immediately after the spin-off.

Strategic Intent

AirTouch has chosen to differentiate itself in its domestic regions based on the concept of "Superior Service Delivery." The company's focus is on being available to its customers 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and on delivering pricing options that meet the customer's needs. AirTouch allows customers to change pricing plans without penalty. The company also emphasizes call clarity and quality and extensive geographic coverage. The key challenges AirTouch faces on a global front is in reducing churn (i.e., the percentage of customers leaving), implementing improved digital technology, managing pressure on service pricing, and maintaining profit margins by focusing on cost reduction. Other challenges include creating a domestic national presence.

Company Structure

AirTouch is decentralized. Regions have been developed in the U.S. market and are run autonomously with respect to pricing decisions, marketing campaigns, and customer care operations. Each region is run as a profit center. Its European operations also are run independently from each other to be able to respond to the competitive issues unique to the specific countries. All employees are shareowners in the company, and the average age of the workforce is in the low to mid-30s. Both companies are comparable in terms of size and exhibit operating profit margins in the mid-to-high teens. AirTouch has substantially less leverage than Vodafone.

Merger Highlights

Vodafone began exploratory talks with AirTouch as early as 1996 on a variety of options ranging from partnerships to a merger. Merger talks continued informally until late 1998 when they were formally broken off. Bell Atlantic, interested in expanding its own mobile phone business's geographic coverage, immediately jumped into the void by proposing to AirTouch that together they form a new wireless company. In early 1999, Vodafone once again entered the fray, sparking a sharp takeover battle for AirTouch. Vodafone emerged victorious by mid-1999.

Motivation for the Merger

Shared Vision

The merger would create a more competitive, global wireless telecommunications company than either company could achieve separately. Moreover, both firms shared the same vision of the telecommunications industry. Mobile telecommunications is believed to be the among the fastest-growing segment of the telecommunications industry, and over time mobile voice will replace large amounts of telecommunications traffic carried by fixed-line networks and will serve as a major platform for voice and data communication. Both companies believe that mobile penetration will reach 50% in developed countries by 2003 and 55% and 65% in the United States and developed European countries, respectively, by 2005.

Complementary Assets

Scale, operating strength, and complementary assets were given as compelling reasons for the merger. The combination of AirTouch and Vodafone would create the largest mobile telecommunication company at the time, with significant presence in the United Kingdom, United States, continental Europe, and Asian Pacific region. The scale and scope of the operations is expected to make the combined firms the vendor of choice for business travelers and international corporations. Interests in operations in many countries will make Vodafone AirTouch more attractive as a partner for other international fixed and mobile telecommunications providers. The combined scale of the companies also is expected to enhance its ability to develop existing networks and to be in the forefront of providing technologically advanced products and services.

Synergy

Anticipated synergies include after-tax cost savings of $340 million annually by the fiscal year ending March 31, 2002. The estimated net present value of these synergies is $3.6 billion discounted at 9%. The cost savings arise from global purchasing and operating efficiencies, including volume discounts, lower leased line costs, more efficient voice and data networks, savings in development and purchase of third-generation mobile handsets, infrastructure, and software. Revenues should be enhanced through the provision of more international coverage and through the bundling of services for corporate customers that operate as multinational businesses and business travelers.

AirTouch's Board Analyzes Options

Morgan Stanley, AirTouch's investment banker, provided analyses of the current prices of the Vodafone and Bell Atlantic stocks, their historical trading ranges, and the anticipated trading prices of both companies' stock on completion of the merger and on redistribution of the stock to the general public. Both offers were structured so as to constitute essentially tax-free reorganizations. The Vodafone proposal would qualify as a Type A reorganization under the Internal Revenue Service Code; hence, it would be tax-free, except for the cash portion of the offer, for U.S. holders of AirTouch common and holders of preferred who converted their shares before the merger. The Bell Atlantic offer would qualify as a Type B tax-free reorganization. Table 1 highlights the primary characteristics of the form of payment (total consideration) of the two competing offers.

Table 1. Camparis an of Farm of PaymentTotal Consideration Vodafone Bell Atlantic 5 shares of Vodafone common plus \ 9 for each 1.54 shares of Bell Atlantic for each share of AirTouch common share of AirTouch common subject to the transaction being treated as a pooling of interest under U.S. GAAP. Share exchange ratio adjusted upward 9 months out to reflect the payment of dividends on the Bell Atlantic stock. A share exchange ratio collar would be used to ensure that Air Touch shareholders would receive shares valued at \ 80.08 . If the average closing price of Bell Atlantic stock were less than \ 48 , the exchange ratio would be increased to 1.6683 . If the price exceeded \ 52 the exchange rate would remain at 1.54.

The collar guarantees the price of Bell Atlantic stock for the Air Touch shareholders because and both equal . Morgan Stanley's primary conclusions were as follows:

Morgan Stanley’s primary conclusions were as follows:

1. Bell Atlantic had a current market value of $83 per share of AirTouch stock based on the $53.81 closing price of Bell Atlantic common stock on January 14, 1999. The collar would maintain the price at $80.08 per share if the price of Bell Atlantic stock during a specified period before closing were between $48 and $52 per share.

2. The Vodafone proposal had a current market value of $97 per share of AirTouch stock based on Vodafone’s ordinary shares (i.e., common) on January 17, 1999.

3. Following the merger, the market value of the Vodafone American Depository Shares (ADSs) to be received by AirTouch shareholders under the Vodafone proposal could decrease.

4. Following the merger, the market value of Bell Atlantic’s stock also could decrease, particularly in light of the expectation that the proposed transaction would dilute Bell Atlantic’s EPS by more than 10% through 2002.

In addition to Vodafone’s higher value, the board tended to favor the Vodafone offer because it involved less regulatory uncertainty. As U.S. corporations, a merger between AirTouch and Bell Atlantic was likely to receive substantial scrutiny from the U.S. Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, and the FCC. Moreover, although both proposals could be completed tax-free, except for the small cash component of the Vodafone offer, the Vodafone offer was not subject to achieving any specific accounting treatment such as pooling of interests under U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

Recognizing their fiduciary responsibility to review all legitimate offers in a balanced manner, the AirTouch board also considered a number of factors that made the Vodafone proposal less attractive. The failure to do so would no doubt trigger shareholder lawsuits. The major factors that detracted from the Vodafone proposal were that it would not result in a national presence in the United States, the higher volatility of its stock, and the additional debt Vodafone would have to assume to pay the cash portion of the purchase price. Despite these concerns, the higher offer price from Vodafone (i.e., $97 to $83) won the day.

Acquisition Vehicle and Post Closing Organization

In the merger, AirTouch became a wholly owned subsidiary of Vodafone. Vodafone issued common shares valued at $52.4 billion based on the closing Vodafone ADS on April 20, 1999. In addition, Vodafone paid AirTouch shareholders $5.5 billion in cash. On completion of the merger, Vodafone changed its name to Vodafone AirTouch Public Limited Company. Vodafone created a wholly owned subsidiary, Appollo Merger Incorporated, as the acquisition vehicle. Using a reverse triangular merger, Appollo was merged into AirTouch. AirTouch constituted the surviving legal entity. AirTouch shareholders received Vodafone voting stock and cash for their AirTouch shares. Both the AirTouch and Appollo shares were canceled. After the merger, AirTouch shareholders owned slightly less than 50% of the equity of the new company, Vodafone AirTouch. By using the reverse merger to convey ownership of the AirTouch shares, Vodafone was able to ensure that all FCC licenses and AirTouch franchise rights were conveyed legally to Vodafone. However, Vodafone was unable to avoid seeking shareholder approval using this method. Vodafone ADS’s traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). Because the amount of new shares being issued exceeded 20% of Vodafone’s outstanding voting stock, the NYSE required that Vodafone solicit its shareholders for approval of the proposed merger.

Following this transaction, the highly aggressive Vodafone went on to consummate the largest merger in history in 2000 by combining with Germany’s telecommunications powerhouse, Mannesmann, for $180 billion. Including assumed debt, the total purchase price paid by Vodafone AirTouch for Mannesmann soared to $198 billion. Vodafone AirTouch was well on its way to establishing itself as a global cellular phone powerhouse.

-Did the AirTouch board make the right decision? Why or why not?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (45)

(45)

The Type C reorganization is used when it is essential for the acquirer not to assume any undisclosed liabilities.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (37)

(37)

A transaction generally will be considered non-taxable to the seller or target firm's shareholder if it involves the purchase of the target's stock or assets for substantially all cash, notes, or some other nonequity consideration.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

In a forward triangular merger, the target firm's tax attributes in the form of any tax loss carry forwards or carrybacks or investment tax credits carry over to the acquirer because the target ceases to exist.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (29)

(29)

In a purchase of assets, the buyer retains the target's tax attributes.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (46)

(46)

Higher bids involving stock and cash may be less attractive than a lower all-cash bid due to the uncertain nature of the value of the acquirer’s stock.

Master limited partnerships represent an alternative means for financing a transaction in industries in which cash flows are relatively predictable.

Energy pipeline company Southern Union (Southern) offered significant synergistic opportunities for competitors Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) and The Williams Companies (Williams). Increasing interest in natural gas as a less polluting but still affordable alternative to coal and oil motivated both ETE and Williams to pursue Southern in mid-2011. Williams, already the nation’s largest pipeline company, accounting for about 12% of the nation’s natural gas distribution by volume, viewed the acquisition as a means of solidifying its premier position in the energy distribution industry. ETE saw Southern as a way of doubling its pipeline capacity and catapulting itself into the number-one position in the industry.

ETE is a publicly traded partnership and is the general partner and owns 100% of the incentive distribution rights of Energy Transfer Partners, L.P. ( ETP), consisting of approximately 50.2 million ETP limited partnership units. The firm also is the general partner and owns 100% of the distribution rights of Regency Energy Partners (REP), consisting of approximately 26.3 million REP limited partnership units. Williams manages most of its pipeline assets through its primary publicly traded master limited partnership known as Williams Partners. Southern owns and operates more than 20,000 miles of pipelines in the United States (Southeast, Midwest, and Great lakes regions as well as Texas and New Mexico). It also owns local gas distribution companies that serve more than half a million end users in Missouri and Massachusetts.

While both ETE and Williams were attracted to Southern because the firm’s shares were believed to be undervalued, the potential synergies also are significant. ETE would transform the firm by expanding its business into the Midwest and Florida and offers a very good complement to ETE’s existing Texas-focused operations. For Williams, it would create the dominant natural gas pipeline system for the Midwest and Northeast and give it ownership interests in two pipelines running into Florida.

Despite the transition of exploration and production companies to liquids for distribution, Southern continued to trade, largely as an annuity offering a steady, predictable financial return. During the six-month period prior to the start of the bidding war, Southern’s stock was caught in a trading range between $27 and $30 per share. That changed in mid-June, when a $33-per-share bid from ETE, consisting of both cash and stock valued by Southern at $4.2 billion, put Southern in “play.” The initial ETE offer was immediately followed by a series of four offers and counteroffers, resulting in an all-cash counteroffer of $44 per share from The Williams Companies, valuing Southern at $5.5 billion. This bid was later topped with an ETE offer of $44.25 per Southern share, boosting Southern’s valuation to approximately $5.6 billion.

Williams’s $44 all-cash offer did not include a financing contingency, but it did include a “hell or high water” clause that would commit the company to taking all necessary steps to obtain regulatory approval; later ETE added a similar provision to their proposal. The clause is meant to assuage Southern shareholder concerns that a deal with Williams or ETE could lead to antitrust lawsuits in states like Florida. The bidding boosted Southern’s shares from a prebid share price of $28 to a final purchase price of $44.25 per share.

Williams argued, to no avail, that its bid was superior to ETE’s, in that its value was certain, in contrast to ETE’s, which gave Southern’s shareholders a choice to receive $40 per share or 0.903 ETE common units whose value was subject to fluctuations in the demand for energy. ETE pointed out not only that their bid was higher than Williams’ but also that shareholders could choose to make their payout tax free if they are paid in stock. The final ETE bid quickly received the backing of Southern’s two biggest shareholders, the firm’s founder and chairman, George Lindemann, and its president, Eric D. Herschmann.

ETE removed any concerns about the firm’s ability to finance the cash portion of the transaction when it announced on August 5, 2011, that it had received financing commitments for $3.7 billion from a syndicate consisting of 11 U.S. and foreign banks. The firm also announced that it had received regulatory approval from the Federal Trade Commission to complete the transaction.

As part of the agreement with ETE, Southern contributed its 50% interest in Citrus Corporation to Energy Transfer Partners for $2 billion. The cash proceeds from the transfer will be used to repay a portion of the acquisition financing and to repay existing Southern Union debt in order for Southern to maintain its investment-grade credit rating. Following completion of the deal, ETE moved Southern’s pipeline assets into Energy Transfer Partners and Regency Energy Partners, eliminating their being subject to double taxation. These actions helped to offset a portion of the purchase price paid to acquire Southern Union.

In retrospect, ETE may have invited the Williams bid because of the confusing nature of its initial bid. According to the firm’s first bid, Southern shareholders would receive Series B units that would yield at least 8.25%. However, depending on the outcome of a series of subsequent events, they could end up getting a combination of cash, ETE common, and Energy Transfer Partners’ common or continuing to hold those Series B units. Some of the possible outcomes would be tax free to Southern shareholders and some taxable. In contrast, The Williams bid is a straightforward all-cash bid whose value is unambiguous and represented an 18% premium for Southern shareholders. The disadvantage of the Williams bid is that it would be taxable; furthermore, it was contingent on Williams’ completing full due diligence.

-If you were a Southern shareholder, would you have found the Williams or the Energy Transfer Equity bid more attractive? Explain your answer.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (35)

(35)

The acquirer must be careful that not too large a proportion of the purchase price be composed of cash, because this might not meet the IRS's requirement for continuity of interests of the target shareholders and disqualify the transaction as a Type A reorganization.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (34)

(34)

If the transaction is tax-free, the acquiring company is able to transfer or carry over the target's tax basis to its own financial statements.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (32)

(32)

Showing 21 - 40 of 125

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)