Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

Shell corporations may be attractive for investors interested in capitalizing on the intangible value associated with the existing corporate shell. This could include name recognition; licenses, patents, and other forms of intellectual properties; and underutilized assets such as warehouse space and fully depreciated equipment with some economic life remaining.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (23)

(23)

What are common reasons for a private firm to go public? What are the advantages and disadvantages or doing so? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Shell Game: Going Public through Reverse Mergers

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Key Points

Reverse mergers represent an alternative to an initial public offering (IPO) for a private company wanting to “go public.”

The challenge with reverse mergers often is gaining access to accurate financial statements and quantifying current or potential liabilities.

Performing adequate due diligence may be difficult, but it is the key to reducing risk.

______________________________________________________________________________

The highly liquid U.S. equity markets have proven to be an attractive way of gaining access to capital for both privately owned domestic and foreign firms. Common ways of doing so have involved IPOs and reverse mergers. While both methods allow the private firm’s shares to be publicly traded, only the IPO necessarily results in raising capital, which affects the length of time and complexity of the process of “going-public.”

To undertake a reverse merger, a firm finds a shell corporation with relatively few shareholders who are interested in selling their stock. The shell corporation’s shareholders often are interested in either selling their shares for cash, owning even a relatively small portion of a financially viable company to recover their initial investments, or transferring the shell’s liabilities to new investors. Alternatively, the private firm may merge with an existing special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) already registered for public stock trading. SPACs are shell, or “blank-check,” companies that have no operations but go public with the intention of merging with or acquiring a company with the proceeds of the SPAC’s IPO.

In a merger, it is common for the surviving firm to be viewed as the acquirer, since its shareholders usually end up with a majority ownership stake in the merged firms; the other party to the merger is viewed as the target firm because its former shareholders often hold only a minority interest in the combined companies. In a reverse merger, the opposite happens. Even though the publicly traded shell company survives the merger, with the private firm becoming its wholly owned subsidiary, the former shareholders of the private firm end up with a majority ownership stake in the combined firms. While conventional IPOs can take months to complete, reverse mergers can take only a few weeks. Moreover, as the reverse merger is solely a mechanism to convert a private company into a public entity, the process is less dependent on financial market conditions because the company often is not proposing to raise capital.

The speed with which a firm can “go public” as compared to an IPO often is attractive to foreign firms desirous of entering U.S. capital markets quickly. In recent years, private equity investors have found the comparative ease of the reverse merger process convenient, because it has enabled them to take public their investments in both domestic and foreign firms. In recent years the story of the rapid growth of Chinese firms has held considerable allure for investors, prompting a flurry of reverse mergers involving Chinese-based firms. With speed comes additional risk. Shell company shareholders may simply be looking for investors to take over their liabilities, such as pending litigation, safety hazards, environmental problems, and unpaid tax liabilities. To prevent the public shell’s shareholders from dumping their shares immediately following the merger, investors are required to hold their shares for a specific period of time. The recent entry of Chinese firms into the U.S. public equity markets illustrates the potential for fraud. Of the 159 Chinese-based firms that have been listed since 2006 via a reverse merger, 36 have been suspended or have halted trading in the United States after auditors found significant accounting issues. Eleven more firms have been delisted from major U.S. stock exchanges.

Huiheng Medical (Huiheng) is one such firm that came under SEC scrutiny, having first listed its shares on the over-the-counter (OTC) market in early 2008. The firm claimed it was China’s leading provider of gamma-ray technology, a cancer-fighting technology, and boasted of having a strong order backlog and access to Western management expertise through a joint venture. What follows is a discussion of how the firm went public and the participants in that process. The firms involved in the reverse merger process included Mill Basin Technologies (Mill), a Nevada incorporated and publicly listed shell corporation, and Allied Moral Holdings (Allied), a privately owned Virgin Islands company with subsidiaries, including Huiheng Medical, primarily in China. Mill was the successor firm to Pinewood Imports (Pinewood), a Nevada-based corporation, formed in November 2002 to import pine molding. Ceasing operations in September 2006 to become a shell corporation, Pinewood changed its name to Mill Basin Technologies. The firm began to search for a merger partner and registered shares for public trading in 2006 in anticipation of raising funds.

The reverse merger process employed by Allied, the privately owned operating company and owner of Huiheng, to merge with Mill, the public shell corporation, early in 2008 to become a publicly listed firm is described in the following steps. Allied is the target firm, and Mill is the acquiring firm.

Step 1. Negotiate terms and conditions: Premerger, Mill and Allied had 10,150,000 and 13,000,000 common shares outstanding, respectively. Mill also had 266,666 preferred shares outstanding. Mill and Allied agreed to a merger in which each Allied shareholder would receive one share of Mill stock for each Allied share they held. With Mill as the surviving entity, former Allied shareholders would own 96.65% of Mill’s shares, and Mill’s former shareholders would own the rest.

Step 2. Recapitalize the acquiring firm: Prior to the share exchange, shareholders in Mill, the shell corporation, recapitalized the firm by contributing 9,700,000 of the shares they owned prior to the merger to Treasury stock, effectively reducing the number of Mill common shares outstanding to 450,000 (10,150,000 – 9,700,000). The objective of the recapitalization was to limit the total number of common shares outstanding postmerger in order to support the price of the new firm’s shares. Such recapitalizations often are undertaken to reduce the number of shares outstanding following closing in order to support the combined firms’ share price once it begins to trade on a public exchange. The firm’s earnings per share are increased for a given level of earnings by reducing the number of common shares outstanding.

Step 3. Close the deal: The terms of the merger called for Mill (the acquirer) to purchase 100% of the outstanding Allied (the target) common and preferred shares, which required Mill to issue 13,000,000 new common shares and 266,666 new preferred shares. All premerger Allied shares were cancelled. Mill Basin Technologies was renamed Huiheng Medical, reflecting potential investor interest at that time in both Chinese firms and in the healthcare

Without the reduction in Mill’s premerger shares outstanding, total shares outstanding postmerger would have been 23,150,000 [10,150,000 (Mill shares premerger) + 13,000,000 (Allied shares premerger)] rather than the 13,450,000 after the recapitalization.

industry. See Exhibit 10.4 for an illustration of the premerger recapitalization of Mill, the postmerger equity structure of the combined firms, and the resulting ownership distribution.

While Huiheng traded as high as $13 in late 2008, it plummeted to $1.60 in early 2012, reflecting the failure of the firm to achieve any significant revenue and income in the cancer market, an inability to get an auditing firm to approve their financial statements, and the absence of any significant order backlog. Having reported net income as high as $9 million in 2007, just prior to completing the reverse merger, the firm was losing money and burning through its remaining cash. The firm was left looking at alternative applications for its technology, such as preserving food with radiation.

Huiheng’s SEC filings state that the firm designs, develops, and markets radiation therapy systems used to treat cancer and acknowledge that the firm had experienced delays selling its technology in China and had no international sales in 2009 or 2010. The filings also show the reverse merger was directed by Richard Propper, a venture capitalist and CEO of Chardan Capital, a San Diego merchant bank with expertise in helping Chinese firms enter the U.S. equity markets. Chardan Capital invested $10 million in Huiheng in exchange for more than 52,000 shares of the firm’s preferred stock. Chardan and Roth Capital Partners, a California investment bank, were co-underwriters for a planned 2008 Huiheng stock offering that was later withdrawn. Chardan had been fined $40,000 for three violations of short-selling rules from 2005 to 2009. Roth is a defendant in alleged securities’ fraud lawsuits involving other Chinese reverse merger firms.

Exhibit 10.4 Mill Basin Technologies (Mill)

Pre-Merger Equity Structure:

Common 10,150,000

Series A Preferred 266,666

Recapitalized Equity Structure

Common 450,000a

Series A Preferred 266,666

New Mill Shares Issued to Acquire 100% of Allied shares

Common 13,000,000

Series A Preferred 266,666

Post-Merger Equity Structure:

Common 13,450,000b

Series A Preferred 266,666

Post-Merger Ownership Distribution of Common Shares:

Former Allied Shareholders: 96.65% c

Former Mill Shareholders: 3.35%

aMill shareholders contributed 9,700,000 shares of their pre-merger holdings to treasury stock cutting the number of Mill shares outstanding to 450,000 in order to reduce the total number of shares outstanding postmerger, which would equal Mill’s premerger shares outstanding plus the newly issued shares. This also could have been achieved by the Mill shareholders agreeing to a reverse stock split. The 10,150,000 pre-merger Mill shares outstanding could be reduced to 450,000 through a reverse split in which Mill shareholders receive 1 new Mill share for each 22.555 outstanding prior to the merger.

bPost-Merger Mill Basin Technologies’ capital structure equals the 450,000 premerger Mill common shares resulting from the recapitalization plus the 13,000,000 newly issued common shares plus 266,666 Series A preferred shares.

c(13,000,000/13,450,000)

Huiheng ran into legal problems soon after its reverse merger. Harborview Master Fund, Diverse Trading Ltd., and Monarch Capital Fund, institutional investors having a controlling interest in Huiheng, approved the reverse merger and invested $1.25 million in exchange for stock. However, they sued Huiheng and Chardan Capital in 2009 as Huiheng’s promise of orders failed to materialize. The lawsuit charged that Huiheng bribed Chinese hospital officials to win purchasing deals. The firm’s initial investors forced the firm to buy back their shares as a result of a legal settlement of their lawsuit in which they argued that the firm had committed fraud when it “went public.” The lawsuit alleged that the firm’s public statements about the efficacy of its technology and order backlog were highly inflated. Huiheng and its codefendants settled out of court in 2010 with no admission of liability by buying back some of its stock. In 2011, the firm had difficulty in collecting receivables and generating cash. That same year, Huiheng’s operations in China were struggling and were on the verge of ceasing production.

-Who are the key participants in the

(Essay)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

Employee benefit levels in private firms are almost always mandated by state or federal law and

therefore cannot be changed.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

It is rare that the owner or a family member is either an investor in or an owner of a vendor supplying products or services to the family owned firm.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (28)

(28)

An investor in a small company generally has little difficulty in selling their shares because of the high demand for small businesses.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

What is the marketability discount and what are common ways of estimating this discount?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (45)

(45)

An investor is interested in making a minority equity investment in a small privately held firm. Because of the nature of the business, she concludes that it would be difficult to sell her interest in the business quickly. Therefore, she believes that the discount for the lack of marketability to be 25%. She also estimates that if she were to acquire a controlling interest in the business, the control premium would be 15%. Based on this information, what should be the discount rate for making a minority investment in this firm? What should she pay for 20% of the business if she believes the value of the entire business to be $1 million.

(Essay)

4.7/5  (38)

(38)

Empirical evidence suggests that discounts have declined in recent years.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Taking Advantage of a “Cupcake Bubble”

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Key Points

Financing growth represents a common challenge for most small businesses.

Selling a portion of the business either to private investors or in a public offering represents a common way for small businesses to finance major expansion plans.

____________________________________________________________________________

When Crumbs first opened in 2003 on the upper west side of Manhattan, the bakery offered three varieties of cupcakes among 150 other items. When the cupcakes became increasingly popular, the bakery began introducing cupcakes with different toppings and decorations. The firm’s founders, Jason and Mia Bauer, followed a straightforward business model: Hold costs down, and minimize investment in equipment. Although all of Crumbs’ cupcake recipes are Mia Bauer’s, there are no kitchens or ovens on the premises. Instead, Crumbs outsources all of the baking activities to commercial facilities. The firm avoids advertising, preferring to give away free cupcakes when it opens a new store and to rely on “word of mouth.” By keeping costs low, the firm has expanded without adding debt. The firm targets locations with high daytime “foot traffic,” such as urban markets. In 2010, the firm sold 13 million cupcakes through 34 locations, accounting for $31 million in revenue and $2.5 million in earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation. Crumbs’ success spawned a desire to accelerate growth by opening up as many as 200 new locations by 2014. The challenge was how to finance such a rapid expansion.

The Bauers were no strangers to raising capital to finance the ongoing growth of their business, having sold one-half of the firm to Edwin Lewis, former CEO of Tommy Hilfiger, for $10 million in 2008. This enabled them to reinvest a portion in the business to sustain growth as well as to draw cash out of the business for their personal use. However, this time the magnitude of their financing requirements proved daunting. The couple was reluctant to burden the business with excessive debt, well aware that this had contributed to the demise of so many other rapidly growing businesses. Equity could be sold directly in the private placement market or to the public. Private placements could be expensive and may not provide the amount of financing needed; tapping the public markets directly through an IPO required dealing with underwriters and a level of financial expertise they lacked. Selling to another firm seemed to satisfy best their primary objectives: Get access to capital, retain their top management positions, and utilize the financial expertise of others to tap the public capital markets and to share in any future value creation.

The 57th Street General Acquisition Corporation (57th Street), a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, appeared to meet their needs. In May 2010, 57th Street raised $54.5 million through an IPO, with the proceeds placed in a trust pending the completion of planned acquisitions. One year later, 57th Street announced it had acquired Crumbs for $27 million in cash and $39 million in 57th Street stock. On June 30, 2011, 57th announced that NASDAQ had approved the listing of its common stock, giving Crumbs a market value of nearly $60 million.

Panda Ethanol Goes Public in a Shell Corporation

In early 2007, Panda Ethanol, owner of ethanol plants in west Texas, decided to explore the possibility of taking its ethanol production business public to take advantage of the high valuations placed on ethanol-related companies in the public market at that time. The firm was confronted with the choice of taking the company public through an initial public offering or by combining with a publicly traded shell corporation through a reverse merger.

After enlisting the services of a local investment banker, Grove Street Investors, Panda chose to "go public" through a reverse merger. This process entailed finding a shell corporation with relatively few shareholders who were interested in selling their stock. The investment banker identified Cirracor Inc. as a potential merger partner. Cirracor was formed on October 12, 2001, to provide website development services and was traded on the over-the-counter bulletin board market (i.e., a market for very low-priced stocks). The website business was not profitable, and the company had only ten shareholders. As of June 30, 2006, Cirracor listed $4,856 in assets and a negative shareholders' equity of $(259,976). Given the poor financial condition of Cirracor, the firm's shareholders were interested in either selling their shares for cash or owning even a relatively small portion of a financially viable company to recover their initial investments in Cirracor. Acting on behalf of Panda, Grove Street formed a limited liability company, called Grove Panda, and purchased 2.73 million Cirracor common shares, or 78 percent of the company, for about $475,000.

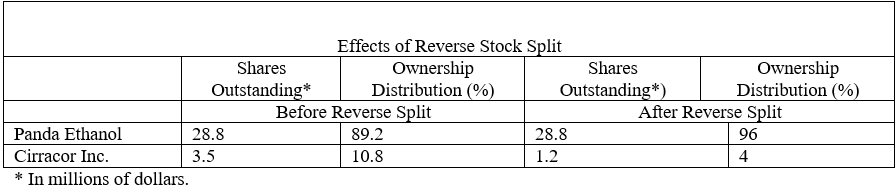

The merger proposal provided for one share of Cirracor common stock to be exchanged for each share of Panda Ethanol common outstanding stock and for Cirracor shareholders to own 4 percent of the newly issued and outstanding common stock of the surviving company. Panda Ethanol shareholders would own the remaining 96 percent. At the end of 2005, Panda had 13.8 million shares outstanding. On June 7, 2007, the merger agreement was amended to permit Panda Ethanol to issue 15 million new shares through a private placement to raise $90 million. This brought the total Panda shares outstanding to 28.8 million. Cirracor common shares outstanding at that time totaled 3.5 million. However, to achieve the agreed-on ownership distribution, the number of Cirracor shares outstanding had to be reduced. This would be accomplished by an approximate three-for-one reverse stock split immediately prior to the completion of the reverse merger (i.e., each Cirracor common share would be converted into 0.340885 shares of Cirracor common stock). As a consequence of the merger, the previous shareholders of Panda Ethanol were issued 28.8 million new shares of Cirracor common stock. The combined firm now has 30 million shares outstanding, with the Cirracor shareholders owning 1.2 million shares. The following table illustrates the effect of the reverse stock split.

A special Cirracor shareholders' meeting was required by Nevada law (i.e., the state in which Cirracor was incorporated) in view of the substantial number of new shares that were to be issued as a result of the merger. The proxy statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission and distributed to Cirracor shareholders indicated that Grove Panda, a 78 percent owner of Cirracor common stock, had already indicated that it would vote its shares for the merger and the reverse stock split. Since Cirracor's articles of incorporation required only a simple majority to approve such matters, it was evident to all that approval was imminent.

On November 7, 2007, Panda completed its merger with Cirracor Inc. As a result of the merger, all shares of Panda Ethanol common stock (other than Panda Ethanol shareholders who had executed their dissenters' rights under Delaware law) would cease to have any rights as a shareholder except the right to receive one share of Cirracor common stock per share of Panda Ethanol common. Panda Ethanol shareholders choosing to exercise their right to dissent would receive a cash payment for the fair value of their stock on the day immediately before closing. Cirracor shareholders had similar dissenting rights under Nevada law. While Cirracor is the surviving corporation, Panda is viewed for accounting purposes as the acquirer. Accordingly, the financial statements shown for the surviving corporation are those of Panda Ethanol.

-Who were Panda Ethanol, Grove Street Investors, Grove Panda, and Cirracor? What were their roles in the case study? Be specific.

A special Cirracor shareholders' meeting was required by Nevada law (i.e., the state in which Cirracor was incorporated) in view of the substantial number of new shares that were to be issued as a result of the merger. The proxy statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission and distributed to Cirracor shareholders indicated that Grove Panda, a 78 percent owner of Cirracor common stock, had already indicated that it would vote its shares for the merger and the reverse stock split. Since Cirracor's articles of incorporation required only a simple majority to approve such matters, it was evident to all that approval was imminent.

On November 7, 2007, Panda completed its merger with Cirracor Inc. As a result of the merger, all shares of Panda Ethanol common stock (other than Panda Ethanol shareholders who had executed their dissenters' rights under Delaware law) would cease to have any rights as a shareholder except the right to receive one share of Cirracor common stock per share of Panda Ethanol common. Panda Ethanol shareholders choosing to exercise their right to dissent would receive a cash payment for the fair value of their stock on the day immediately before closing. Cirracor shareholders had similar dissenting rights under Nevada law. While Cirracor is the surviving corporation, Panda is viewed for accounting purposes as the acquirer. Accordingly, the financial statements shown for the surviving corporation are those of Panda Ethanol.

-Who were Panda Ethanol, Grove Street Investors, Grove Panda, and Cirracor? What were their roles in the case study? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

Despite the lack of public exchanges for privately held firms, Wall Street analysts have ample incentive to analyze such firms in search of emerging companies.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Private firms must file quarterly earnings reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (43)

(43)

Shell Game: Going Public through Reverse Mergers

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Key Points

Reverse mergers represent an alternative to an initial public offering (IPO) for a private company wanting to “go public.”

The challenge with reverse mergers often is gaining access to accurate financial statements and quantifying current or potential liabilities.

Performing adequate due diligence may be difficult, but it is the key to reducing risk.

______________________________________________________________________________

The highly liquid U.S. equity markets have proven to be an attractive way of gaining access to capital for both privately owned domestic and foreign firms. Common ways of doing so have involved IPOs and reverse mergers. While both methods allow the private firm’s shares to be publicly traded, only the IPO necessarily results in raising capital, which affects the length of time and complexity of the process of “going-public.”

To undertake a reverse merger, a firm finds a shell corporation with relatively few shareholders who are interested in selling their stock. The shell corporation’s shareholders often are interested in either selling their shares for cash, owning even a relatively small portion of a financially viable company to recover their initial investments, or transferring the shell’s liabilities to new investors. Alternatively, the private firm may merge with an existing special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) already registered for public stock trading. SPACs are shell, or “blank-check,” companies that have no operations but go public with the intention of merging with or acquiring a company with the proceeds of the SPAC’s IPO.

In a merger, it is common for the surviving firm to be viewed as the acquirer, since its shareholders usually end up with a majority ownership stake in the merged firms; the other party to the merger is viewed as the target firm because its former shareholders often hold only a minority interest in the combined companies. In a reverse merger, the opposite happens. Even though the publicly traded shell company survives the merger, with the private firm becoming its wholly owned subsidiary, the former shareholders of the private firm end up with a majority ownership stake in the combined firms. While conventional IPOs can take months to complete, reverse mergers can take only a few weeks. Moreover, as the reverse merger is solely a mechanism to convert a private company into a public entity, the process is less dependent on financial market conditions because the company often is not proposing to raise capital.

The speed with which a firm can “go public” as compared to an IPO often is attractive to foreign firms desirous of entering U.S. capital markets quickly. In recent years, private equity investors have found the comparative ease of the reverse merger process convenient, because it has enabled them to take public their investments in both domestic and foreign firms. In recent years the story of the rapid growth of Chinese firms has held considerable allure for investors, prompting a flurry of reverse mergers involving Chinese-based firms. With speed comes additional risk. Shell company shareholders may simply be looking for investors to take over their liabilities, such as pending litigation, safety hazards, environmental problems, and unpaid tax liabilities. To prevent the public shell’s shareholders from dumping their shares immediately following the merger, investors are required to hold their shares for a specific period of time. The recent entry of Chinese firms into the U.S. public equity markets illustrates the potential for fraud. Of the 159 Chinese-based firms that have been listed since 2006 via a reverse merger, 36 have been suspended or have halted trading in the United States after auditors found significant accounting issues. Eleven more firms have been delisted from major U.S. stock exchanges.

Huiheng Medical (Huiheng) is one such firm that came under SEC scrutiny, having first listed its shares on the over-the-counter (OTC) market in early 2008. The firm claimed it was China’s leading provider of gamma-ray technology, a cancer-fighting technology, and boasted of having a strong order backlog and access to Western management expertise through a joint venture. What follows is a discussion of how the firm went public and the participants in that process. The firms involved in the reverse merger process included Mill Basin Technologies (Mill), a Nevada incorporated and publicly listed shell corporation, and Allied Moral Holdings (Allied), a privately owned Virgin Islands company with subsidiaries, including Huiheng Medical, primarily in China. Mill was the successor firm to Pinewood Imports (Pinewood), a Nevada-based corporation, formed in November 2002 to import pine molding. Ceasing operations in September 2006 to become a shell corporation, Pinewood changed its name to Mill Basin Technologies. The firm began to search for a merger partner and registered shares for public trading in 2006 in anticipation of raising funds.

The reverse merger process employed by Allied, the privately owned operating company and owner of Huiheng, to merge with Mill, the public shell corporation, early in 2008 to become a publicly listed firm is described in the following steps. Allied is the target firm, and Mill is the acquiring firm.

Step 1. Negotiate terms and conditions: Premerger, Mill and Allied had 10,150,000 and 13,000,000 common shares outstanding, respectively. Mill also had 266,666 preferred shares outstanding. Mill and Allied agreed to a merger in which each Allied shareholder would receive one share of Mill stock for each Allied share they held. With Mill as the surviving entity, former Allied shareholders would own 96.65% of Mill’s shares, and Mill’s former shareholders would own the rest.

Step 2. Recapitalize the acquiring firm: Prior to the share exchange, shareholders in Mill, the shell corporation, recapitalized the firm by contributing 9,700,000 of the shares they owned prior to the merger to Treasury stock, effectively reducing the number of Mill common shares outstanding to 450,000 (10,150,000 – 9,700,000). The objective of the recapitalization was to limit the total number of common shares outstanding postmerger in order to support the price of the new firm’s shares. Such recapitalizations often are undertaken to reduce the number of shares outstanding following closing in order to support the combined firms’ share price once it begins to trade on a public exchange. The firm’s earnings per share are increased for a given level of earnings by reducing the number of common shares outstanding.

Step 3. Close the deal: The terms of the merger called for Mill (the acquirer) to purchase 100% of the outstanding Allied (the target) common and preferred shares, which required Mill to issue 13,000,000 new common shares and 266,666 new preferred shares. All premerger Allied shares were cancelled. Mill Basin Technologies was renamed Huiheng Medical, reflecting potential investor interest at that time in both Chinese firms and in the healthcare

Without the reduction in Mill’s premerger shares outstanding, total shares outstanding postmerger would have been 23,150,000 [10,150,000 (Mill shares premerger) + 13,000,000 (Allied shares premerger)] rather than the 13,450,000 after the recapitalization.

industry. See Exhibit 10.4 for an illustration of the premerger recapitalization of Mill, the postmerger equity structure of the combined firms, and the resulting ownership distribution.

While Huiheng traded as high as $13 in late 2008, it plummeted to $1.60 in early 2012, reflecting the failure of the firm to achieve any significant revenue and income in the cancer market, an inability to get an auditing firm to approve their financial statements, and the absence of any significant order backlog. Having reported net income as high as $9 million in 2007, just prior to completing the reverse merger, the firm was losing money and burning through its remaining cash. The firm was left looking at alternative applications for its technology, such as preserving food with radiation.

Huiheng’s SEC filings state that the firm designs, develops, and markets radiation therapy systems used to treat cancer and acknowledge that the firm had experienced delays selling its technology in China and had no international sales in 2009 or 2010. The filings also show the reverse merger was directed by Richard Propper, a venture capitalist and CEO of Chardan Capital, a San Diego merchant bank with expertise in helping Chinese firms enter the U.S. equity markets. Chardan Capital invested $10 million in Huiheng in exchange for more than 52,000 shares of the firm’s preferred stock. Chardan and Roth Capital Partners, a California investment bank, were co-underwriters for a planned 2008 Huiheng stock offering that was later withdrawn. Chardan had been fined $40,000 for three violations of short-selling rules from 2005 to 2009. Roth is a defendant in alleged securities’ fraud lawsuits involving other Chinese reverse merger firms.

Exhibit 10.4 Mill Basin Technologies (Mill)

Pre-Merger Equity Structure:

Common 10,150,000

Series A Preferred 266,666

Recapitalized Equity Structure

Common 450,000a

Series A Preferred 266,666

New Mill Shares Issued to Acquire 100% of Allied shares

Common 13,000,000

Series A Preferred 266,666

Post-Merger Equity Structure:

Common 13,450,000b

Series A Preferred 266,666

Post-Merger Ownership Distribution of Common Shares:

Former Allied Shareholders: 96.65% c

Former Mill Shareholders: 3.35%

aMill shareholders contributed 9,700,000 shares of their pre-merger holdings to treasury stock cutting the number of Mill shares outstanding to 450,000 in order to reduce the total number of shares outstanding postmerger, which would equal Mill’s premerger shares outstanding plus the newly issued shares. This also could have been achieved by the Mill shareholders agreeing to a reverse stock split. The 10,150,000 pre-merger Mill shares outstanding could be reduced to 450,000 through a reverse split in which Mill shareholders receive 1 new Mill share for each 22.555 outstanding prior to the merger.

bPost-Merger Mill Basin Technologies’ capital structure equals the 450,000 premerger Mill common shares resulting from the recapitalization plus the 13,000,000 newly issued common shares plus 266,666 Series A preferred shares.

c(13,000,000/13,450,000)

Huiheng ran into legal problems soon after its reverse merger. Harborview Master Fund, Diverse Trading Ltd., and Monarch Capital Fund, institutional investors having a controlling interest in Huiheng, approved the reverse merger and invested $1.25 million in exchange for stock. However, they sued Huiheng and Chardan Capital in 2009 as Huiheng’s promise of orders failed to materialize. The lawsuit charged that Huiheng bribed Chinese hospital officials to win purchasing deals. The firm’s initial investors forced the firm to buy back their shares as a result of a legal settlement of their lawsuit in which they argued that the firm had committed fraud when it “went public.” The lawsuit alleged that the firm’s public statements about the efficacy of its technology and order backlog were highly inflated. Huiheng and its codefendants settled out of court in 2010 with no admission of liability by buying back some of its stock. In 2011, the firm had difficulty in collecting receivables and generating cash. That same year, Huiheng’s operations in China were struggling and were on the verge of ceasing production.

-What is a corporate shell and how can they create value?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (40)

(40)

Why is it likely that shares trade at a discount from their value when issued if investors attempted to sell such shares within one year following closing of the reverse merger?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (40)

(40)

Financial information for both public and private firms is equally reliable because their statements are audited by outside accounting firms to ensure that are developed in a manner consistent with GAAP.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

In many countries, family owned firms have been successful because of their shared interests and because investors place a higher value on short-term performance than on the long-term health of the business.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (32)

(32)

A sudden improvement in operating profits in the year in which the business is being offered for sale may suggest that both revenue and expenses had been overstated during the historical period.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

The discount rate may be estimated using all but the one of the following:

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (40)

(40)

Showing 41 - 60 of 127

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)