Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

Chapter 11 reorganization often enables creditors to recover relatively more of their claims than under liquidation.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (34)

(34)

Delta Airlines Rises from the Ashes

-Once in Chapter 11, a firm may be able to negotiate significant contract concessions with unions as well as its creditors.

-A restructured firm emerging from Chapter 11 often is a much smaller but more efficient operation than prior to its entry into bankruptcy.

______________________________________________________________________________________

On April 30, 2007, Delta Airlines emerged from bankruptcy leaner but still an independent carrier after a 19-month reorganization during which it successfully fought off a $10 billion hostile takeover attempt by US Airways. The challenge facing Delta's management was to convince creditors that it would become more valuable as an independent carrier than it would be as part of US Airways.

Ravaged by escalating jet fuel prices and intensified competition from low-fare, low-cost carriers, Delta had lost $6.1 billion since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. The final crisis occurred in early August 2005 when the bank that was processing the airline's Visa and MasterCard ticket purchases started holding back money until passengers had completed their trips as protection in case of a bankruptcy filing. The bank was concerned that it would have to refund the passengers' ticket prices if the airline curtailed flights and the bank had to be reimbursed by the airline. This move by the bank cost the airline $650 million, further straining the carrier's already limited cash reserves. Delta's creditors were becoming increasingly concerned about the airline's ability to meet its financial obligations. Running out of cash and unable to borrow to satisfy current working capital requirements, the airline felt compelled to seek the protection of the bankruptcy court in late August 2005.

Delta's decision to declare bankruptcy occurred about the same time as a similar decision by Northwest Airlines. United Airlines and US Airways were already in bankruptcy. United had been in bankruptcy almost three years at the time Delta entered Chapter 11, and US Airways had been in bankruptcy court twice since the 9/11 terrorist attacks shook the airline industry. At the time Delta declared bankruptcy, about one-half of the domestic carrier capacity was operating under bankruptcy court oversight.

Delta underwent substantial restructuring of its operations. An important component of the restructuring effort involved turning over its underfunded pilot's pension plans to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), a federal pension insurance agency, while winning concessions on wages and work rules from its pilots. The agreement with the pilot's union would save the airline $280 million annually, and the pilots would be paid 14 percent less than they were before the airline declared bankruptcy. To achieve an agreement with its pilots to transfer control of their pension plan to the PBGC, Delta agreed to give the union a $650 million interest-bearing note upon terminating and transferring the pension plans to the PBGC. The union would then use the airline's payments on the note to provide supplemental payments to members who would lose retirement benefits due to the PBGC limits on the amount of Delta's pension obligations it would be willing to pay. The pact covers more than 6,000 pilots.

The overhaul of Delta, the nation's third largest airline, left it a much smaller carrier than the one that sought protection of the bankruptcy court. Delta shed about one jet in six used by its mainline operations at the time of the bankruptcy filing, and it cut more than 20 percent of the 60,000 employees it had just prior to entering Chapter 11. Delta's domestic carrying capacity fell by about 10 percent since it petitioned for Chapter 11 reorganization, allowing it to fill about 84 percent of its seats on U.S. routes. This compared to only 72 percent when it filed for bankruptcy. The much higher utilization of its planes boosted revenue per mile flown by 15 percent since it entered bankruptcy, enabling the airline to better cover its fixed expenses. Delta also sold one of its "feeder" airlines, Atlantic Southeast Airlines, for $425 million.

Delta would have $2.5 billion in exit financing to fund operations and a cost structure of about $3 billion a year less than when it went into bankruptcy. The purpose of the exit financing facility is to repay the company's $2.1 billion debtor-in-possession credit facilities provided by GE Capital and American Express, make other payments required on exiting bankruptcy, and increase its liquidity position. With ten financial institutions providing the loans, the exit facility consisted of a $1.6 billion first-lien revolving credit line, secured by virtually all of the airline's unencumbered assets, and a $900 million second-lien term loan.

As required by the Plan of Reorganization approved by the Bankruptcy Court, Delta cancelled its preplan common stock on April 30, 2007. Holders of preplan common stock did not receive a distribution of any kind under the Plan of Reorganization. The company issued new shares of Delta common stock as payment of bankruptcy claims and as part of a postbankruptcy compensation program for Delta employees. Issued in May 2007, the new shares were listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

-In view of the substantial loss of jobs, as well as wage and benefit reductions, do you believe that firms should be allowed to reorganize in bankruptcy? Explain your answer.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

Calpine Emerges from the Protection of Bankruptcy Court

Following approval of its sixth Plan of Reorganization by the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, Calpine Corporation was able to emerge from Chapter 11 bankruptcy on January 31, 2008. Burdened by excessive debt and court battles with creditors on how to use its cash, the electric utility had sought Chapter 11 protection by petitioning the bankruptcy court in December 2005. After settlements with certain stakeholders, all classes of creditors voted to approve the Plan of Reorganization, which provided for the discharge of claims through the issuance of reorganized Calpine Corporation common stock, cash, or a combination of cash and stock to its creditors.

Shortly after exiting bankruptcy, Calpine cancelled all of its then outstanding common stock and authorized the issuance of 485 million shares of reorganized Calpine Corporation common stock for distribution to holders of unsecured claims. In addition, the firm issued warrants (i.e., securities) to purchase 48.5 million shares of reorganized Calpine Corporation common stock to the holders of the cancelled (i.e., previously outstanding) common stock. The warrants were issued on a pro rata basis reflecting the number of shares of “old common stock” held at the time of cancellation. These warrants carried an exercise price of $23.88 per share and expired on August 25, 2008. Relisted on the New York Stock Exchange, the reorganized Calpine Corporation common stock began trading under the symbol CPN on February 7, 2008, at about $18 per share.

The firm had improved its capital structure while in bankruptcy. On entering bankruptcy, Calpine carried $17.4 billion of debt with an average interest rate of 10.3 percent. By retiring unsecured debt with reorganized Calpine Corporation common stock and selling certain assets, Calpine was able to repay or refinance certain project debt, thereby reducing the prebankruptcy petition debt by approximately $7 billion. On exiting bankruptcy, Calpine negotiated approximately $7.3 billion of secured “exit facilities” (i.e., credit lines) from Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, and Morgan Stanley. About $6.4 billion of these funds were used to satisfy cash payment obligations under the Plan of Reorganization. These obligations included the repayment of a portion of unsecured creditor claims and administrative claims, such as legal and consulting fees, as well as expenses incurred in connection with the “exit facilities” and immediate working capital requirements. On emerging from Chapter 11, the firm carried $10.4 billion of debt with an average interest rate of 8.1 percent.

The Enron Shuffle—A Scandal to Remember

What started in the mid-1980s as essentially a staid "old-economy" business became the poster child in the late 1990s for companies wanting to remake themselves into "new-economy" powerhouses. Unfortunately, what may have started with the best of intentions emerged as one of the biggest business scandals in U.S. history. Enron was created in 1985 as a result of a merger between Houston Natural Gas and Internorth Natural Gas. In 1989, Enron started trading natural gas commodities and eventually became the world's largest buyer and seller of natural gas. In the early 1990s, Enron became the nation's premier electricity marketer and pioneered the development of trading in such commodities as weather derivatives, bandwidth, pulp, paper, and plastics. Enron invested billions in its broadband unit and water and wastewater system management unit and in hard assets overseas. In 2000, Enron reported $101 billion in revenue and a market capitalization of $63 billion.

The Virtual Company

Enron was essentially a company whose trading and risk management business strategy was built on assets largely owned by others. The complex financial maneuvering and off-balance-sheet partnerships that former CEO Jeffrey K. Skilling and chief financial officer Andrew S. Fastow implemented were intended to remove everything from telecommunications fiber to water companies from the firm's balance sheet and into partnerships. What distinguished Enron's partnerships from those commonly used to share risks were their lack of independence from Enron and the use of Enron's stock as collateral to leverage the partnerships. If Enron's stock fell in value, the firm was obligated to issue more shares to the partnership to restore the value of the collateral underlying the debt or immediately repay the debt. Lenders in effect had direct recourse to Enron stock if at any time the partnerships could not repay their loans in full. Rather than limiting risk, Enron was assuming total risk by guaranteeing the loans with its stock.

Enron also engaged in transactions that inflated its earnings, such as selling time on its broadband system to a partnership at inflated prices at a time when the demand for broadband was plummeting. Enron then recorded a substantial profit on such transactions. The partnerships agreed to such transactions because Enron management seems to have exerted disproportionate influence in some instances over partnership decisions, although its ownership interests were very small, often less than 3 percent. Curiously, Enron's outside auditor, Arthur Andersen, had a dual role in these partnerships, collecting fees for helping to set them up and auditing them.

Time to Pay the Piper

At the time the firm filed for bankruptcy on December 2, 2001, it had $13.1 billion in debt on the books of the parent company and another $18.1 billion on the balance sheets of affiliated companies and partnerships. In addition to the partnerships created by Enron, a number of bad investments both in the United States and abroad contributed to the firm's malaise. Meanwhile, Enron's core energy distribution business was deteriorating. Enron was attempting to gain share in a maturing market by paring selling prices. Margins also suffered from poor cost containment.

Dynegy Corp. agreed to buy Enron for $10 billion on November 2, 2001. On November 8, Enron announced that its net income would have to be restated back to 1997, resulting in a $586 million reduction in reported profits. On November 15, chairman Kenneth Lay admitted that the firm had made billions of dollars in bad investments. Four days later, Enron said it would have to repay a $690 million note by mid-December and it might have to take an additional $700 million pretax charge. At the end of the month, Dynegy withdrew its offer and Enron's credit rating was reduced to junk bond status. Enron was responsible for another $3.9 billion owed by its partnerships. Enron had less than $2 billion in cash on hand.

The end came quickly as investors and customers completely lost faith in the energy behemoth as a result of its secrecy and complex financial maneuvers, forcing the firm into bankruptcy in early December. Enron's stock, which had reached a high of $90 per share on August 17, 2001, was trading at less than $1 by December 5, 2001.

In addition to its angry creditors, Enron faced class-action lawsuits by shareholders and employees, whose pensions were invested heavily in Enron stock. Enron also faced intense scrutiny from congressional committees and the U.S. Department of Justice. By the end of 2001, shareholders had lost more than $63 billion from its previous 52-week high, bondholders lost $2.6 billion in the face value of their debt, and banks appeared to be at risk on at least $15 billion of credit they had extended to Enron. In addition, potential losses on uncollateralized derivative contracts totaled $4 billion. Such contracts involved Enron commitments to buy various types of commodities at some point in the future.

Questions remain as to why Wall Street analysts, Arthur Andersen, federal or state regulatory authorities, the credit rating agencies, and the firm's board of directors did not sound the alarm sooner. It is surprising that the audit committee of the Enron board seems to have somehow been unaware of the firm's highly questionable financial maneuvers. Inquiries following the bankruptcy declaration seem to suggest that the audit committee followed all the rules stipulated by federal regulators and stock exchanges regarding director pay, independence, disclosure, and financial expertise. Enron seems to have collapsed in part because such rules did not do what they were supposed to do. For example, paying directors with stock may have aligned their interests with shareholders, but it also is possible to have been a disincentive to question aggressively senior management about their financial dealings.

The Lessons of Enron

Enron may be the best recent example of a complete breakdown in corporate governance, a system intended to protect shareholders. Inside Enron, the board of directors, management, and the audit function failed to do the job. Similarly, the firm's outside auditors, regulators, credit rating agencies, and Wall Street analysts also failed to alert investors. What seems to be apparent is that if the auditors fail to identify incompetence or fraud, the system of safeguards is likely to break down. The cost of failure to those charged with protecting the shareholders, including outside auditors, analysts, credit-rating agencies, and regulators, was simply not high enough to ensure adequate scrutiny.

What may have transpired is that company managers simply undertook aggressive interpretations of accounting principles then challenged auditors to demonstrate that such practices were not in accordance with GAAP accounting rules (Weil, 2002). This type of practice has been going on since the early 1980s and may account for the proliferation of specific accounting rules applicable only to certain transactions to insulate both the firm engaging in the transaction and the auditor reviewing the transaction from subsequent litigation. In one sense, the Enron debacle represents a failure of the free market system and its current shareholder protection mechanisms, in that it took so long for the dramatic Enron shell game to be revealed to the public. However, this incident highlights the remarkable resilience of the free market system. The free market system worked quite effectively in its rapid imposition of discipline in bringing down the Enron house of cards, without any noticeable disruption in energy distribution nationwide.

Epilogue

Due to the complexity of dealing with so many types of creditors, Enron filed its plan with the federal bankruptcy court to reorganize one and a half years after seeking bankruptcy protection on December 2, 2001. The resulting reorganization has been one of the most costly and complex on record, with total legal and consulting fees exceeding $500 million by the end of 2003. More than 350 classes of creditors, including banks, bondholders, and other energy companies that traded with Enron said they were owed about $67 billion.

Under the reorganization plan, unsecured creditors received an estimated 14 cents for each dollar of claims against Enron Corp., while those with claims against Enron North America received an estimated 18.3 cents on the dollar. The money came in cash payments and stock in two holding companies, CrossCountry containing the firm's North American pipeline assets and Prisma Energy International containing the firm's South American operations.

After losing its auditing license in 2004, Arthur Andersen, formerly among the largest auditing firms in the world, ceased operation. In 2006, Andrew Fastow, former Enron chief financial officer, and Lea Fastow plead guilty to several charges of conspiracy to commit fraud. Andrew Fastow received a sentence of 10 years in prison without the possibility of parole. His wife received a much shorter sentence. Also in 2006, Enron chairman Kenneth Lay died while awaiting sentencing, and Enron president Jeffery Skilling received a sentence of 24 years in prison.

Citigroup agreed in early 2008 to pay $1.66 billion to Enron creditors who lost money following the collapse of the firm. Citigroup was the last remaining defendant in what was known as the Mega Claims lawsuit, a bankruptcy lawsuit filed in 2003 against 11 banks and brokerages. The suit alleged that, with the help of banks, Enron kept creditors in the dark about the firm's financial problems through misleading accounting practices. Because of the Mega Claims suit, creditors recovered a total of $5 billion or about 37.4 cents on each dollar owed to them. This lawsuit followed the settlement of a $40 billion class action lawsuit by shareholders, which Citicorp settled in June 2005 for $2 billion.

-In your judgment, what were the major factors contributing to the demise of Enron? Of these factors, which were the most important?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (25)

(25)

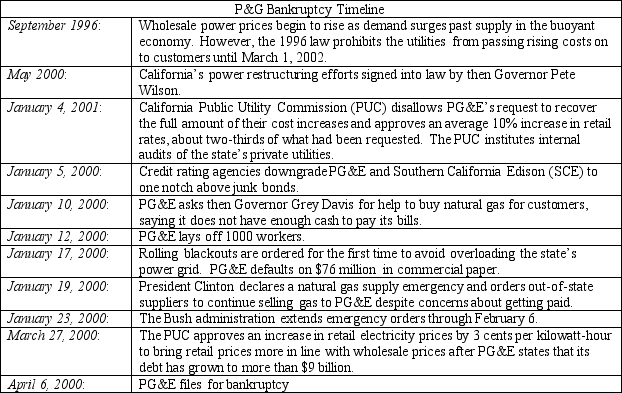

PG&E SEEKS BANKRUPTCY PROTECTION

Pacific, Gas, and Electric (PG&E), the San Francisco-based utility, filed for bankruptcy on April 7, 2001, citing nearly $9 billion in debt and un-reimbursed energy costs. The utility, one of three privately owned utilities in California, serves northern and central California. The intention of the Chapter 11 reorganization was to make the utility solvent again by protecting the firm from lawsuits or any other action by those who are owed money by the utility. The bankruptcy will also allow the utility to deal with all of the firm's debts in a single forum rather than with individual debtors in what had become a highly politicized venue. The following time line outlines the firm's road to bankruptcy.

.

Utility industry analysts saw PG&E's move as largely an effort to escape the political paralysis that had befallen the state's regulatory apparatus. The bankruptcy filing came one day after Governor Davis dropped his opposition to raising retail rates. However, the Governor's reversal came after five month's of negotiations with the state's privately owned utilities on a rescue plan.

PG&E's common shares fell 37 percent on the day the firm filed for reorganization. Fearing a similar fate for San Diego Gas and Electric, the shares of Sempra Energy, SDG&E's parent corporation, also dropped by 35 percent

In an attempt to insulate California ratepayers from escalating wholesale electricity prices, the state entered into a series of 5-to-10 year contracts with electricity power generators that account for more than two-thirds of the state's projected power needs. The last contracts were signed by the state in June 2001. By September, a slowing economy pushed the wholesale price of electricity well below the level the state was required to pay in the "take or pay" contracts the state had just signed. Estimates suggest that California taxpayers will have to pay between $40 and $45 billion in power costs over the next decade depending on what happens to future energy costs. PG&E has continued to supply its customers without disruption or blackout while being under the protection of the bankruptcy court.

Southern California Edison, nearing bankruptcy for reasons similar to those that drove PG&E to seek protection from its creditors, reached agreement with the Public Utility Commission to pay off $3.3 billion in debt owed to power generators from customer revenues. Previously, the PUC had forbid the utility to use monies generated from two previous rate increases for this purpose. The U.S. District Court judge approved the plan on October 5, 2001. While some creditors complained that the settlement was not reassuring because it did not include a timetable for repayment of outstanding debt, others viewed the agreement as a voluntary reorganization plan without going through the expensive process of filing for bankruptcy with the federal court.

-In your judgment, did regulators attenuate or exacerbate the situation? Explain your answer.

.

Utility industry analysts saw PG&E's move as largely an effort to escape the political paralysis that had befallen the state's regulatory apparatus. The bankruptcy filing came one day after Governor Davis dropped his opposition to raising retail rates. However, the Governor's reversal came after five month's of negotiations with the state's privately owned utilities on a rescue plan.

PG&E's common shares fell 37 percent on the day the firm filed for reorganization. Fearing a similar fate for San Diego Gas and Electric, the shares of Sempra Energy, SDG&E's parent corporation, also dropped by 35 percent

In an attempt to insulate California ratepayers from escalating wholesale electricity prices, the state entered into a series of 5-to-10 year contracts with electricity power generators that account for more than two-thirds of the state's projected power needs. The last contracts were signed by the state in June 2001. By September, a slowing economy pushed the wholesale price of electricity well below the level the state was required to pay in the "take or pay" contracts the state had just signed. Estimates suggest that California taxpayers will have to pay between $40 and $45 billion in power costs over the next decade depending on what happens to future energy costs. PG&E has continued to supply its customers without disruption or blackout while being under the protection of the bankruptcy court.

Southern California Edison, nearing bankruptcy for reasons similar to those that drove PG&E to seek protection from its creditors, reached agreement with the Public Utility Commission to pay off $3.3 billion in debt owed to power generators from customer revenues. Previously, the PUC had forbid the utility to use monies generated from two previous rate increases for this purpose. The U.S. District Court judge approved the plan on October 5, 2001. While some creditors complained that the settlement was not reassuring because it did not include a timetable for repayment of outstanding debt, others viewed the agreement as a voluntary reorganization plan without going through the expensive process of filing for bankruptcy with the federal court.

-In your judgment, did regulators attenuate or exacerbate the situation? Explain your answer.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

The debtor firm often initiates the voluntary settlement process, because it generally offers the best chance for the current owners to recover a portion of their investments either by continuing to operate the firm or through a planned liquidation of the firm.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

What types of businesses are most appropriate for Chapter 11 reorganization, Chapter 7 liquidation, or a Section 363 sale?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (31)

(31)

A Reorganized Dana Corporation

Emerges from Bankruptcy Court

Dana Corporation, an automotive parts manufacturer, announced on February 1, 2008, that it had emerged from bankruptcy court with an exit financing facility of $2 billion. The firm had entered Chapter 11 reorganization on March 3, 2006. During the ensuing 21 months, the firm and its constituents identified, agreed on, and won court approval for approximately $440 million to $475 million in annual cost savings and the elimination of unprofitable products. These annual savings resulted from achieving better plant utilization due to changes in union work rules, wage and benefit reductions, the reduction of ongoing obligations for retiree health and welfare costs, and streamlining administrative expenses.

The plan of reorganization accepted by the court, creditors, and investors included a $750 million equity investment provided by Centerbridge Capital Partners to fund a portion of the firm's health-care and pension obligations. Under the plan, shareholders received no payout. Bondholders of some $1.62 billion in various maturities and holders of $1.63 billion in unsecured claims recovered about 60-90 percent of their claims. Centerbridge would acquire $250 million of convertible preferred stock in the reorganized Dana operation, and creditors, who had agreed to support the reorganization plan, could acquire up to $500 million of the convertible preferred shares. The preferred shares were issued as an inducement to get creditors to support the plan of reorganization. Under the reorganization plan, Dana sold some businesses, cut plants in the United States and Canada, reduced its hourly and salaried workforce, and sought price increases on parts from customers.

-Dose the process outlined in this business case seem equitable for all parties to the bankruptcy proceedings? Why? Why not? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

To determine which strategy to pursue, the failing firm's management needs to estimate which of the following:

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (37)

(37)

All of the following are conditions most favorable for reaching settlement outside of bankruptcy court except for

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Prior to the Bankruptcy Abuse Protection and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA), commercial enterprises used Chapter 11 Reorganization to continue operating a business and to repay creditors through a court-approved plan of reorganization.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

Sales within the protection of Chapter 11 reorganization may be accomplished either by a negotiated private sale to a particular purchaser or through a public auction.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (34)

(34)

In liquidation, bankruptcy professionals, including attorneys, accountants, and trustees, often end up with the majority of the proceeds generated by selling the assets of the failing firm.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (40)

(40)

The types of businesses are most appropriate for Chapter 11 reorganization, Chapter 7 liquidation, or a Section 363 sale? What factor(s) drove Hostess into a Section 363 sale?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (33)

(33)

Financially distressed firms also affect communities in which they are located in terms of increasing unemployment and eroding the tax base.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (41)

(41)

The Blockbuster case study illustrates the options available to the creditors and owners of a failing firm. How do you believe creditors and owners might choose among the range of available options?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

All of the following are true about voluntary liquidations except for

(Multiple Choice)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

Chapter 11 reorganization may involve a corporation, sole proprietorship, or partnership.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (33)

(33)

Bankruptcy is a state-level legal proceeding designed to protect the technically or legally insolvent firm from lawsuits by its creditors until a decision can be made to shut down or to continue to operate the firm.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (37)

(37)

Speculate as to why Blockbuster filed a motion with the Court to initiate a Section 363 auction rather than to continue to negotiate a reorganization plan with its creditors to exit Chapter 11.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Photography Icon Kodak Declares Bankruptcy, A Victim of Creative Destruction

Having invented the digital camera, Kodak knew that the longevity of its traditional film business was problematic.

Concerned about protecting its core film business, Kodak was unable to reposition itself fast enough to stave off failure.

Chapter 11 reorganization offers an opportunity to emerge as a viable business, save jobs, minimize creditor losses, and limit the impact on communities.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Economic historian Joseph Schumpeter described the free market process by which new technologies and deregulation create new industries, often at the expense of existing ones, as "creative destruction." In the short run, this process can have a highly disruptive impact on current employees whose skills are made obsolete, investors and business owners whose businesses are no longer competitive, and communities that are ravaged by increasing unemployment and diminished tax revenues. However, in the long run, the process tends to raise living standards by boosting worker productivity and increasing real income and leisure time, stimulating innovation, expanding the range of products and services offered, often at a lower price, to consumers, and to increase tax revenues. Kodak is a recent illustration of this process.

Founded in 1880 by George Eastman, Kodak became the latest giant to fall in the face of advancing technology, announcing that it had filed for the protection of the bankruptcy court early in 2012. Kodak had established the market for camera film and then dominated the marketplace before suffering a series of setbacks over the last 40 years. First foreign competitors, most notably Fujifilm of Japan, undercut Kodak's film prices. Then the increased popularity of digital photography eroded demand for traditional film, eventually causing the firm to cease investment in its traditional film product in 2003. Although it had invented the digital camera, Kodak had failed to develop it further, announcing on February 12, 2012, that it would discontinue its production of such cameras. Kodak's failure to move aggressively into the digital world may have reflected its concern about cannibalizing its core film business. This concern may have ultimately destined the firm for failure.

Kodak closed 13 manufacturing plants and 130 processing labs and had reduced its workforce to 17,000 in 2011 from 63,000 in 2003. In recent years, the firm has undertaken a two-pronged strategy: expanding into the inkjet printer market and initiating patent lawsuits to generate royalty payments from firms allegedly violating Kodak digital patents. Kodak technologies are found in virtually all modern digital cameras, smartphones, and tablet computers. Kodak had raised $3 billion between 2003 and 2010 by reaching settlements with alleged patent infringement companies. But the revenue from litigation dried up in 2011.

With only one profitable year since 2004, the firm eventually ran out of cash. Its market value on the day it announced its bankruptcy filing had slumped to $150 million, compared to $31 billion in 1995. Kodak said it had $5.1 billion in assets and $6.8 billion in debt, rendering the firm insolvent. The Chapter 11 filing was made in the U.S. bankruptcy court in lower New York City and excluded the firm's non-U.S. subsidiaries. The objectives of the bankruptcy filing were to buy time to find buyers for some of its 1,100 digital patents, to continue to shrink its current employment, to reduce significantly its healthcare and pension obligations, and to renegotiate more favorable payment terms on its outstanding debt. Kodak had put the patents up for sale in August 2011 but did not receive any bids, since potential buyers were concerned that they would be required to return the assets by creditors if Kodak filed for bankruptcy protection. While the firm's pension obligations are well funded, the firm owes health benefits to 38,000 U.S. retirees, which in 2011 cost the firm $240 million.

Kodak also announced that it had obtained a $950 million loan from Citibank to keep operating during the bankruptcy process. Moreover, the firm filed new patent infringement suits in March 2012 against a number of competitors, including Fujifilm, Research in Motion (RIM), and Apple, in order to increase the value of its patent portfolios. However, a court ruled in mid-2012 that neither Apple nor RIM had infringed on Kodak patents. In early 2013, Kodak announced that it would put additional assets up for sale (including its camera film business and heavy-duty commercial scanners and software businesses) since the sale of its remaining digital imaging patents raised only $525 million, much less than the nearly $2 billion the firm had expected. The sale of these businesses would cement Kodak's departure from its roots. In late September 2012, Kodak announced that it would suspend the production and sale of consumer inkjet printers. Kodak also received permission from the bankruptcy court judge to terminate the payment of retiree medical, dental, and life insurance benefits for 56,000 retirees at the end of 2012.

Kodak has to demonstrate viability to emerge from Chapter 11 as a reorganized firm or be acquired by another firm. The firm has pinned its remaining hopes for survival on selling commercial printing equipment and services, a business that generated about $2 billion in revenue in 2012 but that may lack the scale to sustain profitability. If it cannot demonstrate viability, Kodak will face liquidation. In either case, the outcome is a sad ending to a photography icon.

-Comment on the fairness of this transaction to the various stakeholders involved. How would you apportion the responsibility for the eventual bankruptcy of Tribune among Sam Zell and his advisors, the Tribune board, and the largely unforeseen collapse of the credit markets in late 2008? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (31)

(31)

Showing 61 - 80 of 118

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)