Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

The filing of a petition triggers an automatic stay once the court accepts the request, which provides a period suspending all judgments, collection activities, foreclosures, and repossessions of property by the creditors on any debt or claim that arose before the filing of the bankruptcy petition.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Do you believe that a strategic bidder like Dish Network has an inherent advantage over a financial bidder in a 363 auction? Explain your answer.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (37)

(37)

If the going concern value is less than the selling or liquidation price, the firm should seek the protection of the bankruptcy court.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (40)

(40)

In the absence of a voluntary settlement out of court, the debtor firm may seek protection from its creditors by initiating bankruptcy or may be forced into bankruptcy by its creditors.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (38)

(38)

What types of businesses are most appropriate for Chapter 11 reorganization, Chapter 7 liquidation, or a Section 363 sale?

(Short Answer)

4.9/5  (44)

(44)

While bankrupt firms generally are unable to meet the listing requirements of the major stock exchanges, their shares may trade in the over-the-counter market.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (38)

(38)

As part of a Chapter 15 proceeding, the U.S. bankruptcy court may authorize a trustee to act in a foreign country on behalf of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (30)

(30)

The purpose of Chapter 15 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code is to prioritize the payment of creditors.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (37)

(37)

Increasingly, distressed companies are choosing to restructure inside of bankruptcy court, rather than reaching a general agreement with creditors before seeking Chapter 11 protection.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

If a creditor is owed a large amount of money, it could become a major or even the controlling shareholder in the reorganized firm.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (34)

(34)

Photography Icon Kodak Declares Bankruptcy, A Victim of Creative Destruction

Having invented the digital camera, Kodak knew that the longevity of its traditional film business was problematic.

Concerned about protecting its core film business, Kodak was unable to reposition itself fast enough to stave off failure.

Chapter 11 reorganization offers an opportunity to emerge as a viable business, save jobs, minimize creditor losses, and limit the impact on communities.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Economic historian Joseph Schumpeter described the free market process by which new technologies and deregulation create new industries, often at the expense of existing ones, as "creative destruction." In the short run, this process can have a highly disruptive impact on current employees whose skills are made obsolete, investors and business owners whose businesses are no longer competitive, and communities that are ravaged by increasing unemployment and diminished tax revenues. However, in the long run, the process tends to raise living standards by boosting worker productivity and increasing real income and leisure time, stimulating innovation, expanding the range of products and services offered, often at a lower price, to consumers, and to increase tax revenues. Kodak is a recent illustration of this process.

Founded in 1880 by George Eastman, Kodak became the latest giant to fall in the face of advancing technology, announcing that it had filed for the protection of the bankruptcy court early in 2012. Kodak had established the market for camera film and then dominated the marketplace before suffering a series of setbacks over the last 40 years. First foreign competitors, most notably Fujifilm of Japan, undercut Kodak's film prices. Then the increased popularity of digital photography eroded demand for traditional film, eventually causing the firm to cease investment in its traditional film product in 2003. Although it had invented the digital camera, Kodak had failed to develop it further, announcing on February 12, 2012, that it would discontinue its production of such cameras. Kodak's failure to move aggressively into the digital world may have reflected its concern about cannibalizing its core film business. This concern may have ultimately destined the firm for failure.

Kodak closed 13 manufacturing plants and 130 processing labs and had reduced its workforce to 17,000 in 2011 from 63,000 in 2003. In recent years, the firm has undertaken a two-pronged strategy: expanding into the inkjet printer market and initiating patent lawsuits to generate royalty payments from firms allegedly violating Kodak digital patents. Kodak technologies are found in virtually all modern digital cameras, smartphones, and tablet computers. Kodak had raised $3 billion between 2003 and 2010 by reaching settlements with alleged patent infringement companies. But the revenue from litigation dried up in 2011.

With only one profitable year since 2004, the firm eventually ran out of cash. Its market value on the day it announced its bankruptcy filing had slumped to $150 million, compared to $31 billion in 1995. Kodak said it had $5.1 billion in assets and $6.8 billion in debt, rendering the firm insolvent. The Chapter 11 filing was made in the U.S. bankruptcy court in lower New York City and excluded the firm's non-U.S. subsidiaries. The objectives of the bankruptcy filing were to buy time to find buyers for some of its 1,100 digital patents, to continue to shrink its current employment, to reduce significantly its healthcare and pension obligations, and to renegotiate more favorable payment terms on its outstanding debt. Kodak had put the patents up for sale in August 2011 but did not receive any bids, since potential buyers were concerned that they would be required to return the assets by creditors if Kodak filed for bankruptcy protection. While the firm's pension obligations are well funded, the firm owes health benefits to 38,000 U.S. retirees, which in 2011 cost the firm $240 million.

Kodak also announced that it had obtained a $950 million loan from Citibank to keep operating during the bankruptcy process. Moreover, the firm filed new patent infringement suits in March 2012 against a number of competitors, including Fujifilm, Research in Motion (RIM), and Apple, in order to increase the value of its patent portfolios. However, a court ruled in mid-2012 that neither Apple nor RIM had infringed on Kodak patents. In early 2013, Kodak announced that it would put additional assets up for sale (including its camera film business and heavy-duty commercial scanners and software businesses) since the sale of its remaining digital imaging patents raised only $525 million, much less than the nearly $2 billion the firm had expected. The sale of these businesses would cement Kodak's departure from its roots. In late September 2012, Kodak announced that it would suspend the production and sale of consumer inkjet printers. Kodak also received permission from the bankruptcy court judge to terminate the payment of retiree medical, dental, and life insurance benefits for 56,000 retirees at the end of 2012.

Kodak has to demonstrate viability to emerge from Chapter 11 as a reorganized firm or be acquired by another firm. The firm has pinned its remaining hopes for survival on selling commercial printing equipment and services, a business that generated about $2 billion in revenue in 2012 but that may lack the scale to sustain profitability. If it cannot demonstrate viability, Kodak will face liquidation. In either case, the outcome is a sad ending to a photography icon.

-Describe the firm's strategy to finance the transaction?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (34)

(34)

Debt restructuring of a bankrupt firm is usually accomplished in which of the following ways:

(Multiple Choice)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Photography Icon Kodak Declares Bankruptcy, A Victim of Creative Destruction

Having invented the digital camera, Kodak knew that the longevity of its traditional film business was problematic.

Concerned about protecting its core film business, Kodak was unable to reposition itself fast enough to stave off failure.

Chapter 11 reorganization offers an opportunity to emerge as a viable business, save jobs, minimize creditor losses, and limit the impact on communities.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Economic historian Joseph Schumpeter described the free market process by which new technologies and deregulation create new industries, often at the expense of existing ones, as "creative destruction." In the short run, this process can have a highly disruptive impact on current employees whose skills are made obsolete, investors and business owners whose businesses are no longer competitive, and communities that are ravaged by increasing unemployment and diminished tax revenues. However, in the long run, the process tends to raise living standards by boosting worker productivity and increasing real income and leisure time, stimulating innovation, expanding the range of products and services offered, often at a lower price, to consumers, and to increase tax revenues. Kodak is a recent illustration of this process.

Founded in 1880 by George Eastman, Kodak became the latest giant to fall in the face of advancing technology, announcing that it had filed for the protection of the bankruptcy court early in 2012. Kodak had established the market for camera film and then dominated the marketplace before suffering a series of setbacks over the last 40 years. First foreign competitors, most notably Fujifilm of Japan, undercut Kodak's film prices. Then the increased popularity of digital photography eroded demand for traditional film, eventually causing the firm to cease investment in its traditional film product in 2003. Although it had invented the digital camera, Kodak had failed to develop it further, announcing on February 12, 2012, that it would discontinue its production of such cameras. Kodak's failure to move aggressively into the digital world may have reflected its concern about cannibalizing its core film business. This concern may have ultimately destined the firm for failure.

Kodak closed 13 manufacturing plants and 130 processing labs and had reduced its workforce to 17,000 in 2011 from 63,000 in 2003. In recent years, the firm has undertaken a two-pronged strategy: expanding into the inkjet printer market and initiating patent lawsuits to generate royalty payments from firms allegedly violating Kodak digital patents. Kodak technologies are found in virtually all modern digital cameras, smartphones, and tablet computers. Kodak had raised $3 billion between 2003 and 2010 by reaching settlements with alleged patent infringement companies. But the revenue from litigation dried up in 2011.

With only one profitable year since 2004, the firm eventually ran out of cash. Its market value on the day it announced its bankruptcy filing had slumped to $150 million, compared to $31 billion in 1995. Kodak said it had $5.1 billion in assets and $6.8 billion in debt, rendering the firm insolvent. The Chapter 11 filing was made in the U.S. bankruptcy court in lower New York City and excluded the firm's non-U.S. subsidiaries. The objectives of the bankruptcy filing were to buy time to find buyers for some of its 1,100 digital patents, to continue to shrink its current employment, to reduce significantly its healthcare and pension obligations, and to renegotiate more favorable payment terms on its outstanding debt. Kodak had put the patents up for sale in August 2011 but did not receive any bids, since potential buyers were concerned that they would be required to return the assets by creditors if Kodak filed for bankruptcy protection. While the firm's pension obligations are well funded, the firm owes health benefits to 38,000 U.S. retirees, which in 2011 cost the firm $240 million.

Kodak also announced that it had obtained a $950 million loan from Citibank to keep operating during the bankruptcy process. Moreover, the firm filed new patent infringement suits in March 2012 against a number of competitors, including Fujifilm, Research in Motion (RIM), and Apple, in order to increase the value of its patent portfolios. However, a court ruled in mid-2012 that neither Apple nor RIM had infringed on Kodak patents. In early 2013, Kodak announced that it would put additional assets up for sale (including its camera film business and heavy-duty commercial scanners and software businesses) since the sale of its remaining digital imaging patents raised only $525 million, much less than the nearly $2 billion the firm had expected. The sale of these businesses would cement Kodak's departure from its roots. In late September 2012, Kodak announced that it would suspend the production and sale of consumer inkjet printers. Kodak also received permission from the bankruptcy court judge to terminate the payment of retiree medical, dental, and life insurance benefits for 56,000 retirees at the end of 2012.

Kodak has to demonstrate viability to emerge from Chapter 11 as a reorganized firm or be acquired by another firm. The firm has pinned its remaining hopes for survival on selling commercial printing equipment and services, a business that generated about $2 billion in revenue in 2012 but that may lack the scale to sustain profitability. If it cannot demonstrate viability, Kodak will face liquidation. In either case, the outcome is a sad ending to a photography icon.

-To what extent do you believe the factors contributing to Tribune's bankruptcy were beyond the control of management? To what extent do you believe past mismanagement may have contributed to the bankruptcy?

(Essay)

4.7/5  (35)

(35)

The General Motors’ Bankruptcy—The Largest Government-Sponsored Bailout in U.S. History

Rarely has a firm fallen as far and as fast as General Motors. Founded in 1908, GM dominated the car industry through the early 1950s with its share of the U.S. car market reaching 54 percent in 1954, which proved to be the firm’s high water mark. Efforts in the 1980s to cut costs by building brands on common platforms blurred their distinctiveness. Following increasing healthcare and pension benefits paid to employees, concessions made to unions in the early 1990s to pay workers even when their plants were shut down reduced the ability of the firm to adjust to changes in the cyclical car market. GM was increasingly burdened by so-called legacy costs (i.e., healthcare and pension obligations to a growing retiree population). Over time, GM’s labor costs soared compared to the firm’s major competitors. To cover these costs, GM continued to make higher margin medium to full-size cars and trucks, which in the wake of higher gas prices could only be sold with the help of highly attractive incentive programs. Forced to support an escalating array of brands, the firm was unable to provide sufficient marketing funds for any one of its brands.

With the onset of one of the worst global recessions in the post–World War II years, auto sales worldwide collapsed by the end of 2008. All automakers’ sales and cash flows plummeted. Unlike Ford, GM and Chrysler were unable to satisfy their financial obligations. The U.S. government, in an unprecedented move, agreed to lend GM and Chrysler $13 billion and $4 billion, respectively. The intent was to buy time to develop an appropriate restructuring plan.

Having essentially ruled out liquidation of GM and Chrysler, continued government financing was contingent on gaining major concessions from all major stakeholders such as lenders, suppliers, and labor unions. With car sales continuing to show harrowing double-digit year over year declines during the first half of 2009, the threat of bankruptcy was used to motivate the disparate parties to come to an agreement. With available cash running perilously low, Chrysler entered bankruptcy in early May and GM on June 1, with the government providing debtor in possession financing during their time in bankruptcy. In its bankruptcy filing for its U.S. and Canadian operations only, GM listed $82.3 billion in assets and $172.8 billion in liabilities. In less than 45 days each, both GM and Chrysler emerged from government-sponsored sales in bankruptcy court, a feat that many thought impossible.

Judge Robert E. Gerber of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court of New York approved the sale in view of the absence of alternatives considered more favorable to the government’s option. GM emerged from the protection of the court on July 10, 2009, in an economic environment characterized by escalating unemployment and eroding consumer income and confidence. Even with less debt and liabilities, fewer employees, the elimination of most “legacy costs,” and a reduced number of dealerships and brands, GM found itself operating in an environment in 2009 in which U.S. vehicle sales totaled an anemic 10.4 million units. This compared to more than 16 million in 2008. GM’s 2009 market share slipped to a post–World War II low of about 19 percent.

While the bankruptcy option had been under consideration for several months, its attraction grew as it became increasingly apparent that time was running out for the cash-strapped firm. Having determined from the outset that liquidation of GM either inside or outside of the protection of bankruptcy would not be considered, the government initially considered a prepackaged bankruptcy in which agreement is obtained among major stakeholders prior to filing for bankruptcy. The presumption is that since agreement with many parties had already been obtained, developing a plan of reorganization to emerge from Chapter 11 would move more quickly. However, this option was not pursued because of the concern that the public would simply view the post–Chapter 11 GM as simply a smaller version of its former self. The government in particular was seeking to position GM as an entirely new firm capable of profitably designing and building cars that the public wanted.

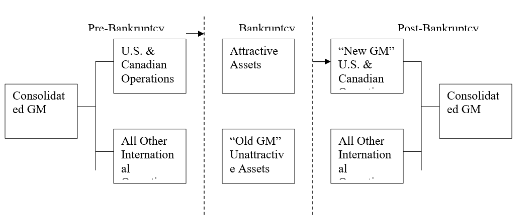

Time was of the essence. The concern was that consumers would not buy GM vehicles while the firm was in bankruptcy. Consequently, a strategy was devised in which GM would be divided into two firms: “old GM,” which would contain the firm’s unwanted assets, and “new GM,” which would own the most attractive assets. “New GM” would then emerge from bankruptcy in a sale to a new company owned by various stakeholder groups, including the U.S. and Canadian governments, a union trust fund, and bondholders. Only GM’s U.S. and Canadian operations were included in the bankruptcy filing. Figure 16.2 illustrates the GM bankruptcy process.

Buying distressed assets can be accomplished through a Chapter 11 plan of reorganization or a post-confirmation trustee. Alternatively, a 363 sale transfers the acquired assets free and clear of any liens, claims, and encumbrances. The sale of GM’s attractive assets to the “new GM” was ultimately completed under Section 363 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Historically, firms used this tactic to sell failing plants and redundant equipment. In recent years, so-called 363 sales have been used to completely restructure businesses, including the 363 sales of entire companies. A 363 sale requires only the approval of the bankruptcy judge, while a plan of reorganization in Chapter 11 must be approved by a substantial number of creditors and meet certain other requirements to be approved. A plan of reorganization is much more comprehensive than a 363 sale in addressing the overall financial situation of the debtor and how its exit strategy from bankruptcy will affect creditors. Once a 363 sale has been consummated and the purchase price paid, the bankruptcy court decides how the proceeds of sale are allocated among secured creditors with liens on the assets sold.

Total financing provided by the U.S. and Canadian (including the province of Ontario) governments amounted to $69.5 billion. U.S. taxpayer-provided financing totaled $60 billion, which consisted of $10 billion in loans and the remainder in equity. The government decided to contribute $50 billion in the form of equity to reduce the burden on GM of paying interest and principal on its outstanding debt. Nearly $20 billion was provided prior to the bankruptcy, $11 billion to finance the firm during the bankruptcy proceedings, and an additional $19 billion in late 2009. In exchange for these funds, the U.S. government owns 60.8 percent of the “new GM’s common shares, while the Canadian and Ontario governments own 11.7 percent in exchange for their investment of $9.5 billion. The United Auto Workers’ new voluntary employee beneficiary association (VEBA) received a 17.5 percent stake in exchange for assuming responsibility for retiree medical and pension obligations. Bondholders and other unsecured creditors received a 10 percent ownership position. The U.S. Treasury and the VEBA also received $2.1 billion and $6.5 billion in preferred shares, respectively.

The new firm, which employs 244,000 workers in 34 countries, intends to further reduce its head count of salaried employees to 27,200 by 2012. The firm will also have shed 21,000 union workers from the 54,000 UAW workers it employed prior to declaring bankruptcy in the United States and close 12 to 20 plants. GM did not include its foreign operations in Europe, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, or Asia Pacific in the Chapter 11 filing. Annual vehicle production capacity for the firm will decline to 10 million vehicles in 2012, compared with 15 to 17 million in 1995. The firm exited bankruptcy with consolidated debt at $17 billion and $9 billion in 9 percent preferred stock, which is payable on a quarterly basis. GM has a new board, with Canada and the UAW healthcare trust each having a seat on the board.

Following bankruptcy, GM has four core brands—Chevrolet, Cadillac, Buick, and GMC—that are sold through 3,600 dealerships, down from its existing 5,969-dealer network. The business plan calls for an IPO whose timing will depend on the firm’s return to sufficient profitability and stock market conditions.

By offloading worker healthcare liabilities to the VEBA trust and seeding it mostly with stock instead of cash, GM has eliminated the need to pay more than $4 billion annually in medical costs. Concessions made by the UAW before GM entered bankruptcy have made GM more competitive in terms of labor costs with Toyota.

Assets to be liquidated by Motors Liquidation Company (i.e., “old GM) were split into four trusts, including one financed by $536 million in existing loans from the federal government. These funds were set aside to clean up 50 million square feet of industrial manufacturing space at 127 locations spread across 14 states. Another $300 million was set aside for property taxes, plant security, and other shutdown expenses. A second trust will handle claims of the owners of GM’s prebankruptcy debt, who are expected to get 10 percent of the equity in General Motors when the firm goes public and warrants to buy additional shares at a later date. The remaining two trusts are intended to process litigation such as asbestos-related claims. The eventual sale of the remaining assets could take four years, with most of the environmental cleanup activities completed within a decade.

Reflecting the overall improvement in the U.S. economy and in its operating performance, GM repaid $10 billion in loans to the U.S. government in April 2010. Seventeen months after emerging from bankruptcy, the firm completed successfully the largest IPO in history on November 17, 2010, raising $23.1 billion. The IPO was intended to raise cash for the firm and to reduce the government’s ownership in the firm, reflecting the firm’s concern that ongoing government ownership hurt sales. Following completion of the IPO, government ownership of GM remained at 33 percent, with the government continuing to have three board representatives.

GM is likely to continue to receive government support for years to come. In an unusual move, GM was allowed to retain $45 billion in tax loss carryforwards, which will eliminate the firm’s tax payments for years to come. Normally, tax losses are preserved following bankruptcy only if the equity in the reorganized company goes to creditors who have been in place for at least 18 months. Despite not meeting this criterion, the Treasury simply overlooked these regulatory requirements in allowing these tax benefits to accrue to GM. Having repaid its outstanding debt to the government, GM continued to owe the U.S. government $36.4 billion ($50 billion less $13.6 billion received from the IPO) at the end of 2010. Assuming a corporate marginal tax rate of 35 percent, the government would lose another $15.75 in future tax payments as a result of the loss carryforward. The government also is providing $7,500 tax credits to buyers of GM’s new all-electric car, the Chevrolet Volt.

-Discuss the relative fairness to the various stakeholders in a bankruptcy of a

more traditional Chapter 11 bankruptcy in which a firm emerges from the protection of the bankruptcy court following the development of a plan of reorganization versus an expedited sale under Section 363 of the federal bankruptcy law. Be specific.

-Discuss the relative fairness to the various stakeholders in a bankruptcy of a

more traditional Chapter 11 bankruptcy in which a firm emerges from the protection of the bankruptcy court following the development of a plan of reorganization versus an expedited sale under Section 363 of the federal bankruptcy law. Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

PG&E SEEKS BANKRUPTCY PROTECTION

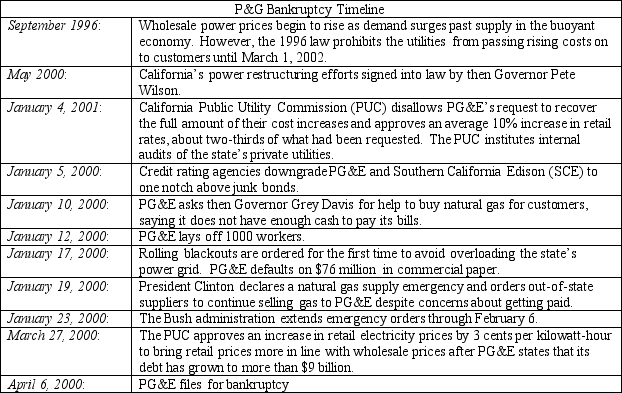

Pacific, Gas, and Electric (PG&E), the San Francisco-based utility, filed for bankruptcy on April 7, 2001, citing nearly $9 billion in debt and un-reimbursed energy costs. The utility, one of three privately owned utilities in California, serves northern and central California. The intention of the Chapter 11 reorganization was to make the utility solvent again by protecting the firm from lawsuits or any other action by those who are owed money by the utility. The bankruptcy will also allow the utility to deal with all of the firm's debts in a single forum rather than with individual debtors in what had become a highly politicized venue. The following time line outlines the firm's road to bankruptcy.

.

Utility industry analysts saw PG&E's move as largely an effort to escape the political paralysis that had befallen the state's regulatory apparatus. The bankruptcy filing came one day after Governor Davis dropped his opposition to raising retail rates. However, the Governor's reversal came after five month's of negotiations with the state's privately owned utilities on a rescue plan.

PG&E's common shares fell 37 percent on the day the firm filed for reorganization. Fearing a similar fate for San Diego Gas and Electric, the shares of Sempra Energy, SDG&E's parent corporation, also dropped by 35 percent

In an attempt to insulate California ratepayers from escalating wholesale electricity prices, the state entered into a series of 5-to-10 year contracts with electricity power generators that account for more than two-thirds of the state's projected power needs. The last contracts were signed by the state in June 2001. By September, a slowing economy pushed the wholesale price of electricity well below the level the state was required to pay in the "take or pay" contracts the state had just signed. Estimates suggest that California taxpayers will have to pay between $40 and $45 billion in power costs over the next decade depending on what happens to future energy costs. PG&E has continued to supply its customers without disruption or blackout while being under the protection of the bankruptcy court.

Southern California Edison, nearing bankruptcy for reasons similar to those that drove PG&E to seek protection from its creditors, reached agreement with the Public Utility Commission to pay off $3.3 billion in debt owed to power generators from customer revenues. Previously, the PUC had forbid the utility to use monies generated from two previous rate increases for this purpose. The U.S. District Court judge approved the plan on October 5, 2001. While some creditors complained that the settlement was not reassuring because it did not include a timetable for repayment of outstanding debt, others viewed the agreement as a voluntary reorganization plan without going through the expensive process of filing for bankruptcy with the federal court.

-PG&E pursued bankruptcy protection, while Southern California Edison did not. What could PG&E have been done differently to avoid bankruptcy?

.

Utility industry analysts saw PG&E's move as largely an effort to escape the political paralysis that had befallen the state's regulatory apparatus. The bankruptcy filing came one day after Governor Davis dropped his opposition to raising retail rates. However, the Governor's reversal came after five month's of negotiations with the state's privately owned utilities on a rescue plan.

PG&E's common shares fell 37 percent on the day the firm filed for reorganization. Fearing a similar fate for San Diego Gas and Electric, the shares of Sempra Energy, SDG&E's parent corporation, also dropped by 35 percent

In an attempt to insulate California ratepayers from escalating wholesale electricity prices, the state entered into a series of 5-to-10 year contracts with electricity power generators that account for more than two-thirds of the state's projected power needs. The last contracts were signed by the state in June 2001. By September, a slowing economy pushed the wholesale price of electricity well below the level the state was required to pay in the "take or pay" contracts the state had just signed. Estimates suggest that California taxpayers will have to pay between $40 and $45 billion in power costs over the next decade depending on what happens to future energy costs. PG&E has continued to supply its customers without disruption or blackout while being under the protection of the bankruptcy court.

Southern California Edison, nearing bankruptcy for reasons similar to those that drove PG&E to seek protection from its creditors, reached agreement with the Public Utility Commission to pay off $3.3 billion in debt owed to power generators from customer revenues. Previously, the PUC had forbid the utility to use monies generated from two previous rate increases for this purpose. The U.S. District Court judge approved the plan on October 5, 2001. While some creditors complained that the settlement was not reassuring because it did not include a timetable for repayment of outstanding debt, others viewed the agreement as a voluntary reorganization plan without going through the expensive process of filing for bankruptcy with the federal court.

-PG&E pursued bankruptcy protection, while Southern California Edison did not. What could PG&E have been done differently to avoid bankruptcy?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (33)

(33)

Delta Airlines Rises from the Ashes

-Once in Chapter 11, a firm may be able to negotiate significant contract concessions with unions as well as its creditors.

-A restructured firm emerging from Chapter 11 often is a much smaller but more efficient operation than prior to its entry into bankruptcy.

______________________________________________________________________________________

On April 30, 2007, Delta Airlines emerged from bankruptcy leaner but still an independent carrier after a 19-month reorganization during which it successfully fought off a $10 billion hostile takeover attempt by US Airways. The challenge facing Delta's management was to convince creditors that it would become more valuable as an independent carrier than it would be as part of US Airways.

Ravaged by escalating jet fuel prices and intensified competition from low-fare, low-cost carriers, Delta had lost $6.1 billion since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. The final crisis occurred in early August 2005 when the bank that was processing the airline's Visa and MasterCard ticket purchases started holding back money until passengers had completed their trips as protection in case of a bankruptcy filing. The bank was concerned that it would have to refund the passengers' ticket prices if the airline curtailed flights and the bank had to be reimbursed by the airline. This move by the bank cost the airline $650 million, further straining the carrier's already limited cash reserves. Delta's creditors were becoming increasingly concerned about the airline's ability to meet its financial obligations. Running out of cash and unable to borrow to satisfy current working capital requirements, the airline felt compelled to seek the protection of the bankruptcy court in late August 2005.

Delta's decision to declare bankruptcy occurred about the same time as a similar decision by Northwest Airlines. United Airlines and US Airways were already in bankruptcy. United had been in bankruptcy almost three years at the time Delta entered Chapter 11, and US Airways had been in bankruptcy court twice since the 9/11 terrorist attacks shook the airline industry. At the time Delta declared bankruptcy, about one-half of the domestic carrier capacity was operating under bankruptcy court oversight.

Delta underwent substantial restructuring of its operations. An important component of the restructuring effort involved turning over its underfunded pilot's pension plans to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), a federal pension insurance agency, while winning concessions on wages and work rules from its pilots. The agreement with the pilot's union would save the airline $280 million annually, and the pilots would be paid 14 percent less than they were before the airline declared bankruptcy. To achieve an agreement with its pilots to transfer control of their pension plan to the PBGC, Delta agreed to give the union a $650 million interest-bearing note upon terminating and transferring the pension plans to the PBGC. The union would then use the airline's payments on the note to provide supplemental payments to members who would lose retirement benefits due to the PBGC limits on the amount of Delta's pension obligations it would be willing to pay. The pact covers more than 6,000 pilots.

The overhaul of Delta, the nation's third largest airline, left it a much smaller carrier than the one that sought protection of the bankruptcy court. Delta shed about one jet in six used by its mainline operations at the time of the bankruptcy filing, and it cut more than 20 percent of the 60,000 employees it had just prior to entering Chapter 11. Delta's domestic carrying capacity fell by about 10 percent since it petitioned for Chapter 11 reorganization, allowing it to fill about 84 percent of its seats on U.S. routes. This compared to only 72 percent when it filed for bankruptcy. The much higher utilization of its planes boosted revenue per mile flown by 15 percent since it entered bankruptcy, enabling the airline to better cover its fixed expenses. Delta also sold one of its "feeder" airlines, Atlantic Southeast Airlines, for $425 million.

Delta would have $2.5 billion in exit financing to fund operations and a cost structure of about $3 billion a year less than when it went into bankruptcy. The purpose of the exit financing facility is to repay the company's $2.1 billion debtor-in-possession credit facilities provided by GE Capital and American Express, make other payments required on exiting bankruptcy, and increase its liquidity position. With ten financial institutions providing the loans, the exit facility consisted of a $1.6 billion first-lien revolving credit line, secured by virtually all of the airline's unencumbered assets, and a $900 million second-lien term loan.

As required by the Plan of Reorganization approved by the Bankruptcy Court, Delta cancelled its preplan common stock on April 30, 2007. Holders of preplan common stock did not receive a distribution of any kind under the Plan of Reorganization. The company issued new shares of Delta common stock as payment of bankruptcy claims and as part of a postbankruptcy compensation program for Delta employees. Issued in May 2007, the new shares were listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

-Comment on the fairness of the bankruptcy process to shareholders, lenders, employees, communities, government, etc. Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (32)

(32)

All of the following are true of the bankruptcy process except for

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

Large companies often have a difficult time achieving out-of-court settlements because they usually have hundreds of creditors.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (33)

(33)

Showing 101 - 118 of 118

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)