Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

A disadvantage of a split-off is that they tend to increase the pressure on the spun-off firm's share price, because shareholders who exchange their stock are more likely to sell the new stock.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (36)

(36)

Restructuring actions may provide tax benefits that cannot be realized without undertaking a restructuring of the business.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (42)

(42)

Unlike a spin-off or carve-out, the parent retains complete ownership of the business for which it has created a tracking stock.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (43)

(43)

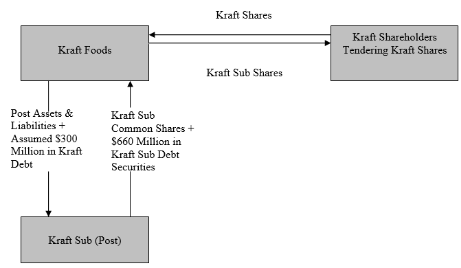

Step 1: Kraft creates a shell subsidiary (Kraft Sub) and transfers Post assets and liabilities and $300 million in Kraft debt into the shell in exchange for Kraft Sub stock plus $660 million in Kraft Sub debt securities. Kraft also implements an exchange offer of Kraft Sub for Kraft common stock.

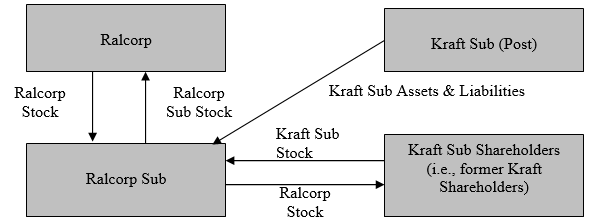

Step 2: Kraft Sub, as an independent company, is merged in a forward triangular tax-free merger with a sub of Ralcorp (Ralcorp Sub) in which Kraft Sub shares are exchanged for Ralcorp shares, with Ralcorp Sub surviving.

Step 2: Kraft Sub, as an independent company, is merged in a forward triangular tax-free merger with a sub of Ralcorp (Ralcorp Sub) in which Kraft Sub shares are exchanged for Ralcorp shares, with Ralcorp Sub surviving.

Sara Lee Attempts to Create Value through Restructuring

After spurning a series of takeover offers, Sara Lee, a global consumer goods company, announced in early 2011 its intention to split the firm into two separate publicly traded companies. The two companies would consist of the firm’s North American retail and food service division and its international beverage business. The announcement comes after a long string of restructuring efforts designed to increase shareholder value. It remains to be seen if the latest effort will be any more successful than earlier efforts.

Reflecting a flawed business strategy, Sara Lee had struggled for more than a decade to create value for its shareholders by radically restructuring its portfolio of businesses. The firm’s business strategy had evolved from one designed in the mid-1980s to market a broad array of consumer products from baked goods to coffee to underwear under the highly recognizable brand name of Sara Lee into one that was designed to refocus the firm on the faster-growing food and beverage and apparel businesses. Despite acquiring several European manufacturers of processed meats in the early 1990s, the company’s profits and share price continued to flounder.

In September 1997, Sara Lee embarked on a major restructuring effort designed to boost both profits, which had been growing by about 6% during the previous five years, and the company’s lagging share price. The restructuring program was intended to reduce the firm’s degree of vertical integration, shifting from a manufacturing and sales orientation to one focused on marketing the firm’s top brands. The firm increasingly viewed itself as more of a marketing than a manufacturing enterprise.

Sara Lee outsourced or sold 110 manufacturing and distribution facilities over the next two years. Nearly 10,000 employees, representing 7% of the workforce, were laid off. The proceeds from the sale of facilities and the cost savings from outsourcing were either reinvested in the firm’s core food businesses or used to repurchase $3 billion in company stock. 1n 1999 and 2000, the firm acquired several brands in an effort to bolster its core coffee operations, including such names as Chock Full o’Nuts, Hills Bros, and Chase & Sanborn.

Despite these restructuring efforts, the firm’s stock price continued to drift lower. In an attempt to reverse the firm’s misfortunes, the firm announced an even more ambitious restructuring plan in 2000. Sara Lee would focus on three main areas: food and beverages, underwear, and household products. The restructuring efforts resulted in the shutdown of a number of meat packing plants and a number of small divestitures, resulting in a 10% reduction (about 13,000 people) in the firm’s workforce. Sara Lee also completed the largest acquisition in its history, purchasing The Earthgrains Company for $1.9 billion plus the assumption of $0.9 billion in debt. With annual revenue of $2.6 billion, Earthgrains specialized in fresh packaged bread and refrigerated dough. However, despite ongoing restructuring activities, Sara Lee continued to underperform the broader stock market indices.

In February 2005, Sara Lee executed its most ambitious plan to transform the firm into a company focused on the global food, beverage, and household and body care businesses. To this end, the firm announced plans to dispose of 40% of its revenues, totaling more than $8 billion, including its apparel, European packaged meats, U.S. retail coffee, and direct sales businesses.

In 2006, the firm announced that it had completed the sale of its branded apparel business in Europe, Global Body Care and European Detergents units, and its European meat processing operations. Furthermore, the firm spun off its U.S. Branded Apparel unit into a separate publicly traded firm called HanesBrands Inc. The firm raised more than $3.7 billion in cash from the divestitures. The firm was now focused on its core businesses: food, beverages, and household and body care.

In late 2008, Sara Lee announced that it would close its kosher meat processing business and sold its retail coffee business. In 2009, the firm sold its Household and Body Care business to Unilever for $1.6 billion and its hair care business to Procter & Gamble for $0.4 billion.

In 2010, the proceeds of the divestitures made the prior year were used to repurchase $1.3 billion of Sara Lee’s outstanding shares. The firm also announced its intention to repurchase another $3 billion of its shares during the next three years. If completed, this would amount to about one-third of its approximate $10 billion market capitalization at the end of 2010.

What remains of the firm are food brands in North America, including Hillshire Farm, Ball Park, and Jimmy Dean processed meats and Sara Lee baked goods and Earthgrains. A food distribution unit will also remain in North America, as will its beverage and bakery operations. Sara Lee is rapidly moving to become a food, beverage, and bakery firm. As it becomes more focused, it could become a takeover target.

Has the 2005 restructuring program worked? To answer this question, it is necessary to determine the percentage change in Sara Lee’s share price from the announcement date of the restructuring program to the end of 2010, as well as the percentage change in the share price of HanesBrands Inc., which was spun off on August 18, 2006. Sara Lee shareholders of record received one share of HanesBrands Inc. for every eight Sara Lee shares they held.

Sara Lee’s share price jumped by 6% on the February 21, 2004 announcement date, closing at $19.56. Six years later, the stock price ended 2010 at $14.90, an approximate 24% decline since the announcement of the restructuring program in early 2005. Immediately following the spinoff, HanesBrands’ stock traded at $22.06 per share; at the end of 2010, the stock traded at $25.99, a 17.8% increase.

A shareholder owning 100 Sara Lee shares when the spin-off was announced would have been entitled to 12.5 HanesBrands shares. However, they would have actually received 12 shares plus $11.03 for fractional shares (i.e., 0.5 × $22.06).

A shareholder of record who had 100 Sara Lee shares on the announcement date of the restructuring program and held their shares until the end of 2010 would have seen their investment decline 24% from $1,956 (100 shares × $19.56 per share) to $1,486.56 by the end of 2010. However, this would have been partially offset by the appreciation of the HanesBrands shares between 2006 and 2010. Therefore, the total value of the hypothetical shareholder’s investment would have decreased by 7.5% from $1,956 to $1,809.47 (i.e., $1,486.56 + 12 HanesBrands shares × $25.99 + $11.03). This compares to a more modest 5% loss for investors who put the same $1,956 into a Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index fund during the same period.

Why did Sara Lee underperform the broader stock market indices during this period? Despite the cumulative buyback of more than $4 billion of its outstanding stock, Sara Lee’s fully diluted earnings per share dropped from $0.90 per share in 2005 to $0.52 per share in 2009. Furthermore, the book value per share, a proxy for the breakup or liquidation value of the firm, dropped from $3.28 in 2005 to $2.93 in 2009, reflecting the ongoing divestiture program. While the HanesBrands spin-off did create value for the shareholder, the amount was far too modest to offset the decline in Sara Lee’s market value. During the same period, total revenue grew at a tepid average annual rate of about 3% to about $13 billion in 2009.

-Explain why Sara Lee may have chosen to spin-off rather than to divest HanesBrands Inc.? Be specific.

Sara Lee Attempts to Create Value through Restructuring

After spurning a series of takeover offers, Sara Lee, a global consumer goods company, announced in early 2011 its intention to split the firm into two separate publicly traded companies. The two companies would consist of the firm’s North American retail and food service division and its international beverage business. The announcement comes after a long string of restructuring efforts designed to increase shareholder value. It remains to be seen if the latest effort will be any more successful than earlier efforts.

Reflecting a flawed business strategy, Sara Lee had struggled for more than a decade to create value for its shareholders by radically restructuring its portfolio of businesses. The firm’s business strategy had evolved from one designed in the mid-1980s to market a broad array of consumer products from baked goods to coffee to underwear under the highly recognizable brand name of Sara Lee into one that was designed to refocus the firm on the faster-growing food and beverage and apparel businesses. Despite acquiring several European manufacturers of processed meats in the early 1990s, the company’s profits and share price continued to flounder.

In September 1997, Sara Lee embarked on a major restructuring effort designed to boost both profits, which had been growing by about 6% during the previous five years, and the company’s lagging share price. The restructuring program was intended to reduce the firm’s degree of vertical integration, shifting from a manufacturing and sales orientation to one focused on marketing the firm’s top brands. The firm increasingly viewed itself as more of a marketing than a manufacturing enterprise.

Sara Lee outsourced or sold 110 manufacturing and distribution facilities over the next two years. Nearly 10,000 employees, representing 7% of the workforce, were laid off. The proceeds from the sale of facilities and the cost savings from outsourcing were either reinvested in the firm’s core food businesses or used to repurchase $3 billion in company stock. 1n 1999 and 2000, the firm acquired several brands in an effort to bolster its core coffee operations, including such names as Chock Full o’Nuts, Hills Bros, and Chase & Sanborn.

Despite these restructuring efforts, the firm’s stock price continued to drift lower. In an attempt to reverse the firm’s misfortunes, the firm announced an even more ambitious restructuring plan in 2000. Sara Lee would focus on three main areas: food and beverages, underwear, and household products. The restructuring efforts resulted in the shutdown of a number of meat packing plants and a number of small divestitures, resulting in a 10% reduction (about 13,000 people) in the firm’s workforce. Sara Lee also completed the largest acquisition in its history, purchasing The Earthgrains Company for $1.9 billion plus the assumption of $0.9 billion in debt. With annual revenue of $2.6 billion, Earthgrains specialized in fresh packaged bread and refrigerated dough. However, despite ongoing restructuring activities, Sara Lee continued to underperform the broader stock market indices.

In February 2005, Sara Lee executed its most ambitious plan to transform the firm into a company focused on the global food, beverage, and household and body care businesses. To this end, the firm announced plans to dispose of 40% of its revenues, totaling more than $8 billion, including its apparel, European packaged meats, U.S. retail coffee, and direct sales businesses.

In 2006, the firm announced that it had completed the sale of its branded apparel business in Europe, Global Body Care and European Detergents units, and its European meat processing operations. Furthermore, the firm spun off its U.S. Branded Apparel unit into a separate publicly traded firm called HanesBrands Inc. The firm raised more than $3.7 billion in cash from the divestitures. The firm was now focused on its core businesses: food, beverages, and household and body care.

In late 2008, Sara Lee announced that it would close its kosher meat processing business and sold its retail coffee business. In 2009, the firm sold its Household and Body Care business to Unilever for $1.6 billion and its hair care business to Procter & Gamble for $0.4 billion.

In 2010, the proceeds of the divestitures made the prior year were used to repurchase $1.3 billion of Sara Lee’s outstanding shares. The firm also announced its intention to repurchase another $3 billion of its shares during the next three years. If completed, this would amount to about one-third of its approximate $10 billion market capitalization at the end of 2010.

What remains of the firm are food brands in North America, including Hillshire Farm, Ball Park, and Jimmy Dean processed meats and Sara Lee baked goods and Earthgrains. A food distribution unit will also remain in North America, as will its beverage and bakery operations. Sara Lee is rapidly moving to become a food, beverage, and bakery firm. As it becomes more focused, it could become a takeover target.

Has the 2005 restructuring program worked? To answer this question, it is necessary to determine the percentage change in Sara Lee’s share price from the announcement date of the restructuring program to the end of 2010, as well as the percentage change in the share price of HanesBrands Inc., which was spun off on August 18, 2006. Sara Lee shareholders of record received one share of HanesBrands Inc. for every eight Sara Lee shares they held.

Sara Lee’s share price jumped by 6% on the February 21, 2004 announcement date, closing at $19.56. Six years later, the stock price ended 2010 at $14.90, an approximate 24% decline since the announcement of the restructuring program in early 2005. Immediately following the spinoff, HanesBrands’ stock traded at $22.06 per share; at the end of 2010, the stock traded at $25.99, a 17.8% increase.

A shareholder owning 100 Sara Lee shares when the spin-off was announced would have been entitled to 12.5 HanesBrands shares. However, they would have actually received 12 shares plus $11.03 for fractional shares (i.e., 0.5 × $22.06).

A shareholder of record who had 100 Sara Lee shares on the announcement date of the restructuring program and held their shares until the end of 2010 would have seen their investment decline 24% from $1,956 (100 shares × $19.56 per share) to $1,486.56 by the end of 2010. However, this would have been partially offset by the appreciation of the HanesBrands shares between 2006 and 2010. Therefore, the total value of the hypothetical shareholder’s investment would have decreased by 7.5% from $1,956 to $1,809.47 (i.e., $1,486.56 + 12 HanesBrands shares × $25.99 + $11.03). This compares to a more modest 5% loss for investors who put the same $1,956 into a Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index fund during the same period.

Why did Sara Lee underperform the broader stock market indices during this period? Despite the cumulative buyback of more than $4 billion of its outstanding stock, Sara Lee’s fully diluted earnings per share dropped from $0.90 per share in 2005 to $0.52 per share in 2009. Furthermore, the book value per share, a proxy for the breakup or liquidation value of the firm, dropped from $3.28 in 2005 to $2.93 in 2009, reflecting the ongoing divestiture program. While the HanesBrands spin-off did create value for the shareholder, the amount was far too modest to offset the decline in Sara Lee’s market value. During the same period, total revenue grew at a tepid average annual rate of about 3% to about $13 billion in 2009.

-Explain why Sara Lee may have chosen to spin-off rather than to divest HanesBrands Inc.? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.7/5  (44)

(44)

In an equity carve-out, the cash raised by the subsidiary in this manner may be transferred to the parent as a dividend or as an inter-company loan.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (32)

(32)

In a private solicitation, the parent firm may hire an investment banker or undertake on its own to identify potential buyers to be contacted.

(True/False)

4.7/5  (42)

(42)

The Anatomy of a Spin-Off-Northrop Grumman Exits the Shipbuilding Business

There are many ways a firm can choose to separate itself from one of its operations.

Which restructuring method is used reflects the firm's objectives and circumstances.

______________________________________________________________________________

In an effort to focus on more attractive growth markets, Northrop Grumman Corporation (NGC), a global leader in aerospace, communications, defense, and security systems, announced that it would exit its mature shipbuilding business on October 15, 2010. Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), the largest military U.S. shipbuilder and a wholly owned subsidiary of NGC, had been under pressure to cut costs amidst increased competition from competitors such as General Dynamics and a slowdown in orders from the U.S. Navy. Nor did the outlook for the shipbuilding industry look like it would improve any time soon.

Given the limited synergy between shipbuilding and HII's other businesses, HII's operations were largely independent of NGC's other units. NGC's management and board argued that their decision to separate from the shipbuilding business would enable both NGC and HII to focus on those areas they knew best. Moreover, given the shipbuilding business's greater ongoing capital requirements, HII would find it easier to tap capital markets directly rather than to compete with other NGC operations for financing. Finally, investors would be better able to value businesses (NGC and HII) whose operations were more focused.

After reviewing a range of options, NGC pursued a spin-off as the most efficient way to separate itself from its shipbuilding operations. If properly structured, spin-offs are tax free to shareholders. Furthermore, management argued that they could be completed in a timelier manner and were less disruptive to current operations than an outright sale of the business. The spin-off represented about one-sixth of NGC's $36 billion in 2010 revenue. Effective March 31, 2011, all of the outstanding stock of HII was spun off to NGC shareholders through a pro rata distribution to shareholders of record on March 30, 2011. Each NGC shareholder received one HII common share for every six shares of NGC common stock held.

The share-exchange ratio of one share of HII common for each six shares of NGC common was calculated by dividing HII's 48.8 million common shares (having a par value of $.01) by the 298 million NGC shares outstanding. Since fractional shares were created, shareholders owning 100 shares would be entitled to 16.6667 shares-100/6. In this instance, the shareholder would receive 16 HII shares and the cash equivalent of 0.6667 shares. The cash to pay for fractional shares came from the aggregation of all fractional shares, which were subsequently sold in the public market. The cash proceeds were then distributed to NGC shareholders on a pro rata basis and were taxable to the extent a taxable gain is incurred by the shareholder.

The spin-off process involved an internal reorganization of NGC businesses, a Separation and Distribution Agreement, and finally the actual distribution of HII shares to NGC shareholders. The internal reorganization and subsequent spin-off is illustrated in Figure 16.4. NGC (referred to as Current Northrop Grumman Corporation) first reorganized its businesses such that the firm would become a holding company whose primary investments would include Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) and Northrop Grumman Systems Corporation (i.e., all other non-shipbuilding operations). HII was formed in anticipation of the spin-off as a holding company for NGC's shipbuilding business, which had been previously known as Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding (NGSB). NGSB was changed to Huntington Ingalls Industries Company following the spin-off. Reflecting the new organizational structure, Current Northrop Grumman common stock was exchanged for stock in New Northrop Grumman Corporation. This internal reorganization was followed by the distribution of HII stock to NGC's common shareholders.

Following the spin-off, HII became a separate company from NGC, with NGC having no ownership interest in HII. Renamed Titan II, Current NGC became a direct, wholly owned subsidiary of HII and held no material assets or liabilities other than Current NGC's guarantees of HII performance under certain HII shipbuilding contracts (under way prior to the spin-off and guaranteed by NGC) and HII's obligations to repay intercompany loans owed to NGC. New NGC changed its name to Northrop Grumman Corporation. The board of directors remained the same following the reorganization.

No gain or loss was incurred by common shareholders because the exchange of stock between the Current and New Northrop Grumman corporations did not change the shareholders' tax basis in the stock. Similarly, no gain or loss was incurred by shareholders with the distribution of HII's stock, since there was no change in the total value of their investment. That is, the value of the HII shares were offset by a corresponding reduction in the value of NGC shares, reflecting the loss of HII's cash flows.

Before the spin-off, HII entered into a Separation and Distribution Agreement with NGC that governed the relationship between HII and NGC after completion of the spin-off and provided for the allocation between the two firms of assets, liabilities, and obligations (e.g., employee benefits, intellectual property, information technology, insurance, and tax-related assets and liabilities). The agreement also provided that NGC and HII each would indemnify (compensate) the other against any liabilities arising out of their respective businesses. As part of the agreement, HII agreed not to engage in any transactions, such as mergers or acquisitions, involving share-for-share exchanges that would change the ownership of the firm by more than 50% for at least two years following the transaction. A change in control could violate the IRS's "continuity of interest" requirement and jeopardize the tax-free status of the spin-off. Consequently, HII put in place certain takeover defenses to make takeovers difficult.

-Why do businesses that have been spun off from their parent often immediately put antitakeover defenses in place?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (42)

(42)

As part of its restructuring plan, a holding company plans to undertake an IPO for 35 percent of the shares it owns in a subsidiary. The sale of these shares would be called a

(Multiple Choice)

4.9/5  (30)

(30)

The Warner Music Group is Sold at Auction

In selling a business, a firm may choose either to negotiate with a single potential buyer, to control the number of potential bidders, or to engage in a public auction.

The auction process often is viewed as the most effective way to get the highest price for a business to be sold; however, far from simple, an auction can be both a chaotic and a time-consuming procedure.

Auctions may be most suitable for businesses whose value is largely intangible or for “hard-to-value” businesses.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

In early 2011, the Warner Music Group (WMG), the third largest of the “big four” recorded-music companies, consisted of two separate businesses: one showing high growth potential and the other with declining revenues. Of WMG’s $3 billion in annual revenue, 82% came from sales of recorded music, with the remainder attributed to royalty payments for the use of music owned by the firm. Of the two, only recorded music has suffered revenue declines, due to piracy, aggressive pricing of online music sales, and the bankruptcy of many record retailers and wholesalers. In contrast, music publishing has grown as a result of diverse revenue streams from radio, television, advertising, and other sources. Music publishing also is benefiting from digital music downloads and the proliferation of cellphone ringtones.

In 2004, Warner Music’s parent at the time, Time Warner Inc., agreed to sell the business to a consortium led by THL Partners for $2.6 billion in cash. The group also included Edward Bronfman, Jr. (the Seagram’s heir, who also became the CEO of WMG), Bain Capital, and Providence Equity Partners. Having held the firm for seven years, a long time for private equity investors, its primary investors were seeking a way to cash out of the business, whose long-term fortunes appeared problematic. WMG’s investors were also in a race with Terra Firma Capital Partners, owner of the venerable British record company EMI, which was expected to take EMI public or to sell the business to a strategic buyer. WMG’s investors were concerned that, if EMI were to be sold before WMG, the firm’s exit strategy would be compromised, because there was much speculation that the only logical buyer for WMG was EMI.

By the end of January 2011, WMG had solicited about 70 potential bidders and attracted unsolicited indications of interest from at least 20 others. As this group winnowed through the auction’s three rounds, alliances among the bidders continually changed. In the ensuing auction, WMG’s stock price jumped by 75% from $4.72 per share on January 20 to $8.25 per share, for a total market value of $3.3 billion on May 6, 2011.

In view of the differences between these two businesses, WMG was open to selling the firm in total or in pieces, contributing to the extensive bidder interest. Risk takers were betting on an eventual recovery in recorded-music sales, while risk-averse investors were more likely to focus on music publishing. Prior to the auction, WMG distributed confidentiality agreements to 37 suitors, with 10 actually submitting a preliminary bid by the deadline of February 22, 2011. Of the preliminary bids, four were for the entire company, three for recorded music, and three for music publishing. For the entire firm, prices ranged from a low bid of $6 per share to a high bid of $8.25 per share. For recorded music, bids ranged from a low of $700 million to a high of $1.1 billion. Music publishing bids were almost twice that of recorded music, ranging from a low of $1.45 billion to a high of $2 billion.

For bidders, the objective is to make it to the next round in the auction; for sellers, the objective is less about prices offered during the initial round and more about determining who is committed to the process and who has the financial wherewithal to consummate the deal. According to the firm’s proxy pertaining to the sale, released on May 20, 2011, the subsequent bidding was characterized as a series of ever-changing alliances among bidders, with Access Industries submitting the winning bid. The sale appears to have been a success from the investors’ standpoint, with some speculating that THL alone earned an internal rate of return (including dividends) of 34%.

Motorola Bows to Activist Pressure

Under pressure from activist investor Carl Icahn, Motorola felt compelled to make a dramatic move before its May 2008 shareholders' meeting. Icahn had submitted a slate of four directors to replace those up for reelection and demanded that the wireless handset and network manufacturer take actions to improve profitability. Shares of Motorola, which had a market value of $22 billion, had fallen more than 60% since October 2006, making the firm’s board vulnerable in the proxy contest over director reelections.

Signaling its willingness to take dramatic action, Motorola announced on March 26, 2008, its intention to create two independent, publicly traded companies. The two new companies would consist of the firm's former Mobile Devices operation (including its Home Devices businesses consisting of modems and set-top boxes) and its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business. In addition to the planned spin-off, Motorola agreed to nominate two people supported by Carl Icahn to the firm’s board. Originally scheduled for 2009, the breakup was postponed due to the upheaval in the financial markets that year. The breakup would result in a tax-free distribution to Motorola's shareholders, with shareholders receiving shares of the two independent and publicly traded firms.

The Mobile Devices business designs, manufactures, and sells mobile handsets globally, and it has lost more than $5 billion during the last three years. The Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business manufactures, designs, and services public safety radios, handheld scanners and telecommunications network gear for businesses and government agencies and generates nearly all of the Motorola’s current cash flow. This business also makes network equipment for wireless carriers such as Spring Nextel and Verizon Wireless.

By dividing the company in this manner, Motorola would separate its loss-generating Mobility Devices division from its other businesses. Although the third largest handset manufacturer globally, the handset business had been losing market share to Nokia and Samsung Electronics for years. Following the breakup, the Mobility Devices unit would be renamed Motorola Mobility, and the Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Networks operation would be called Motorola Solutions.

Motorola’s board is seeking to ensure the financial viability of Motorola Mobility by eliminating its outstanding debt and through a cash infusion. To do so, Motorola intends to buy back nearly all of its outstanding $3.9 billion debt and to transfer as much as $4 billion in cash to Motorola Mobility. Furthermore, Motorola Solutions would assume responsibility for the pension obligations of Motorola Mobility. If Motorola Mobility were to be forced into bankruptcy shortly after the breakup, Motorola Solutions may be held legally responsible for some of the business’s liabilities. The court would have to prove that Motorola had conveyed the Mobility Devices unit (renamed Motorola Mobility following the breakup) to its shareholders, fraudulently knowing that the unit’s financial viability was problematic.

Once free of debt and other obligations and flush with cash, Motorola Mobility would be in a better position to make acquisitions and to develop new phones. It would also be more attractive as a takeover target. A stand-alone firm is unencumbered by intercompany relationships, including such things as administrative support or parts and services supplied by other areas of Motorola. Moreover, all liabilities and assets associated with the handset business already would have been identified, making it easier for a potential partner to value the business.

In mid-2010, Motorola Inc. announced that it had reached an agreement with Nokia Siemens Networks, a Finnish-German joint venture, to buy the wireless networks operations, formerly part of its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Network Devices business for $1.2 billion. On January 4, 2011, Motorola Inc. spun off the common shares of Motorola Mobility it held as a tax-free dividend to its shareholders and renamed the firm Motorola Solutions. Each shareholder of record as of December 21, 2010, would receive one share of Motorola Mobility common for every eight shares of Motorola Inc. common stock they held. Table 15.3 shows the timeline of Motorola’s restructuring effort.

Discussion Questions

1. In your judgment, did the breakup of Motorola make sense? Explain your answer.

2. What other restructuring alternatives could Motorola have pursued to increase shareholder value? Why do you believe it pursued this breakup strategy rather than some other option?

Motorola (Beginning 2010) Motorola (Mid-2010) Motorola (Beginning 2011) Mobility Devices Mobility Devices Motorola Mobility spin-off Enterprise Mobility Solutions \& Wireless Networks Enterprise Mobility Solutions* Motorola Inc. renamed Motorola Solutions

Kraft Foods Undertakes Split-Off of Post Cereals in Merger-Related Transaction

In August 2008, Kraft Foods announced an exchange offer related to the split-off of its Post Cereals unit and the closing of the merger of its Post Cereals business into a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ralcorp Holdings. Kraft is a major manufacturer and distributor of foods and beverages; Post is a leading manufacturer of breakfast cereals; and Ralcorp manufactures and distributes brand-name products in grocery and mass merchandise food outlets. The objective of the transaction was to allow Kraft shareholders participating in the exchange offer for Kraft Sub stock to become shareholders in Ralcorp and Kraft to receive almost $1 billion in cash or cash equivalents on a tax-free basis.

Prior to the transaction, Kraft borrowed $300 million from outside lenders and established Kraft Sub, a shell corporation wholly owned by Kraft. Kraft subsequently transferred the Post assets and associated liabilities, along with the liability Kraft incurred in raising $300 million, to Kraft Sub in exchange for all of Kraft Sub’s stock and $660 million in debt securities issued by Kraft Sub to be paid to Kraft at the end of ten years. In effect, Post was conveyed to Kraft Sub in exchange for assuming Kraft’s $300 million liability, 100% of Kraft Sub’s stock, and Kraft Sub debt securities with a principal amount of $660 million. The consideration that Kraft received, consisting of the debt assumption by Kraft Sub, the debt securities from Kraft Sub, and the Kraft Sub stock, is considered tax free to Kraft, since it is viewed simply as an internal reorganization rather than a sale. Kraft later converted to cash the securities received from Kraft Sub by selling them to a consortium of banks.

In the related split-off transaction, Kraft shareholders had the option to exchange their shares of Kraft common stock for shares of Kraft Sub, which owned the assets and liabilities of Post. If Kraft was unable to exchange all of the Kraft Sub common shares, Kraft would distribute the remaining shares as a dividend (i.e., spin-off) on a pro rata basis to Kraft shareholders.

With the completion of the merger of Kraft Sub with Ralcorp Sub (a Ralcorp wholly-owned subsidiary), the common shares of Kraft Sub were exchanged for shares of Ralcorp stock on a one for one basis. Consequently, Kraft shareholders tendering their Kraft shares in the exchange offer owned 0.6606 of a share of Ralcorp stock for each Kraft share exchanged as part of the split-off.

Concurrent with the exchange offer, Kraft closed the merger of Post with Ralcorp. Kraft shareholders received Ralcorp stock valued at $1.6 billion, resulting in their owning 54% of the merged firm. By satisfying the Morris Trust tax code regulations, the transaction was tax free to Kraft shareholders. Ralcorp Sub was later merged into Ralcorp. As such, Ralcorp assumed the liabilities of Ralcorp Sub, including the $660 million owed to Kraft.

The purchase price for Post equaled $2.56 billion. This price consisted of $1.6 billion in Ralcorp stock received by Kraft shareholders and $960 million in cash equivalents received by Kraft. The $960 million included the assumption of the $300 million liability by Kraft Sub and the $660 million in debt securities received from Kraft Sub. The steps involved in the transaction are described

-How might a spin-off create shareholder value for Kraft Foods shareholders?

(Essay)

4.7/5  (38)

(38)

What is the likely impact of the spin-off on Northrop Grumman's share price immediately following the spin-off of Huntington Ingalls assuming no other factors offset it?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (37)

(37)

Since 2001, GE, the world's largest conglomerate, had been underperforming the S&P 500 stock index. In late 2008,

the firm announced that it was considering spinning off its consumer and industrial unit. What do you believe are

GE's motives for their proposed restructuring? Why do you believe they chose a spin-off rather than an alternative

restructuring strategy?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (28)

(28)

The Warner Music Group is Sold at Auction

In selling a business, a firm may choose either to negotiate with a single potential buyer, to control the number of potential bidders, or to engage in a public auction.

The auction process often is viewed as the most effective way to get the highest price for a business to be sold; however, far from simple, an auction can be both a chaotic and a time-consuming procedure.

Auctions may be most suitable for businesses whose value is largely intangible or for “hard-to-value” businesses.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

In early 2011, the Warner Music Group (WMG), the third largest of the “big four” recorded-music companies, consisted of two separate businesses: one showing high growth potential and the other with declining revenues. Of WMG’s $3 billion in annual revenue, 82% came from sales of recorded music, with the remainder attributed to royalty payments for the use of music owned by the firm. Of the two, only recorded music has suffered revenue declines, due to piracy, aggressive pricing of online music sales, and the bankruptcy of many record retailers and wholesalers. In contrast, music publishing has grown as a result of diverse revenue streams from radio, television, advertising, and other sources. Music publishing also is benefiting from digital music downloads and the proliferation of cellphone ringtones.

In 2004, Warner Music’s parent at the time, Time Warner Inc., agreed to sell the business to a consortium led by THL Partners for $2.6 billion in cash. The group also included Edward Bronfman, Jr. (the Seagram’s heir, who also became the CEO of WMG), Bain Capital, and Providence Equity Partners. Having held the firm for seven years, a long time for private equity investors, its primary investors were seeking a way to cash out of the business, whose long-term fortunes appeared problematic. WMG’s investors were also in a race with Terra Firma Capital Partners, owner of the venerable British record company EMI, which was expected to take EMI public or to sell the business to a strategic buyer. WMG’s investors were concerned that, if EMI were to be sold before WMG, the firm’s exit strategy would be compromised, because there was much speculation that the only logical buyer for WMG was EMI.

By the end of January 2011, WMG had solicited about 70 potential bidders and attracted unsolicited indications of interest from at least 20 others. As this group winnowed through the auction’s three rounds, alliances among the bidders continually changed. In the ensuing auction, WMG’s stock price jumped by 75% from $4.72 per share on January 20 to $8.25 per share, for a total market value of $3.3 billion on May 6, 2011.

In view of the differences between these two businesses, WMG was open to selling the firm in total or in pieces, contributing to the extensive bidder interest. Risk takers were betting on an eventual recovery in recorded-music sales, while risk-averse investors were more likely to focus on music publishing. Prior to the auction, WMG distributed confidentiality agreements to 37 suitors, with 10 actually submitting a preliminary bid by the deadline of February 22, 2011. Of the preliminary bids, four were for the entire company, three for recorded music, and three for music publishing. For the entire firm, prices ranged from a low bid of $6 per share to a high bid of $8.25 per share. For recorded music, bids ranged from a low of $700 million to a high of $1.1 billion. Music publishing bids were almost twice that of recorded music, ranging from a low of $1.45 billion to a high of $2 billion.

For bidders, the objective is to make it to the next round in the auction; for sellers, the objective is less about prices offered during the initial round and more about determining who is committed to the process and who has the financial wherewithal to consummate the deal. According to the firm’s proxy pertaining to the sale, released on May 20, 2011, the subsequent bidding was characterized as a series of ever-changing alliances among bidders, with Access Industries submitting the winning bid. The sale appears to have been a success from the investors’ standpoint, with some speculating that THL alone earned an internal rate of return (including dividends) of 34%.

Motorola Bows to Activist Pressure

Under pressure from activist investor Carl Icahn, Motorola felt compelled to make a dramatic move before its May 2008 shareholders' meeting. Icahn had submitted a slate of four directors to replace those up for reelection and demanded that the wireless handset and network manufacturer take actions to improve profitability. Shares of Motorola, which had a market value of $22 billion, had fallen more than 60% since October 2006, making the firm’s board vulnerable in the proxy contest over director reelections.

Signaling its willingness to take dramatic action, Motorola announced on March 26, 2008, its intention to create two independent, publicly traded companies. The two new companies would consist of the firm's former Mobile Devices operation (including its Home Devices businesses consisting of modems and set-top boxes) and its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business. In addition to the planned spin-off, Motorola agreed to nominate two people supported by Carl Icahn to the firm’s board. Originally scheduled for 2009, the breakup was postponed due to the upheaval in the financial markets that year. The breakup would result in a tax-free distribution to Motorola's shareholders, with shareholders receiving shares of the two independent and publicly traded firms.

The Mobile Devices business designs, manufactures, and sells mobile handsets globally, and it has lost more than $5 billion during the last three years. The Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business manufactures, designs, and services public safety radios, handheld scanners and telecommunications network gear for businesses and government agencies and generates nearly all of the Motorola’s current cash flow. This business also makes network equipment for wireless carriers such as Spring Nextel and Verizon Wireless.

By dividing the company in this manner, Motorola would separate its loss-generating Mobility Devices division from its other businesses. Although the third largest handset manufacturer globally, the handset business had been losing market share to Nokia and Samsung Electronics for years. Following the breakup, the Mobility Devices unit would be renamed Motorola Mobility, and the Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Networks operation would be called Motorola Solutions.

Motorola’s board is seeking to ensure the financial viability of Motorola Mobility by eliminating its outstanding debt and through a cash infusion. To do so, Motorola intends to buy back nearly all of its outstanding $3.9 billion debt and to transfer as much as $4 billion in cash to Motorola Mobility. Furthermore, Motorola Solutions would assume responsibility for the pension obligations of Motorola Mobility. If Motorola Mobility were to be forced into bankruptcy shortly after the breakup, Motorola Solutions may be held legally responsible for some of the business’s liabilities. The court would have to prove that Motorola had conveyed the Mobility Devices unit (renamed Motorola Mobility following the breakup) to its shareholders, fraudulently knowing that the unit’s financial viability was problematic.

Once free of debt and other obligations and flush with cash, Motorola Mobility would be in a better position to make acquisitions and to develop new phones. It would also be more attractive as a takeover target. A stand-alone firm is unencumbered by intercompany relationships, including such things as administrative support or parts and services supplied by other areas of Motorola. Moreover, all liabilities and assets associated with the handset business already would have been identified, making it easier for a potential partner to value the business.

In mid-2010, Motorola Inc. announced that it had reached an agreement with Nokia Siemens Networks, a Finnish-German joint venture, to buy the wireless networks operations, formerly part of its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Network Devices business for $1.2 billion. On January 4, 2011, Motorola Inc. spun off the common shares of Motorola Mobility it held as a tax-free dividend to its shareholders and renamed the firm Motorola Solutions. Each shareholder of record as of December 21, 2010, would receive one share of Motorola Mobility common for every eight shares of Motorola Inc. common stock they held. Table 15.3 shows the timeline of Motorola’s restructuring effort.

Discussion Questions

1. In your judgment, did the breakup of Motorola make sense? Explain your answer.

2. What other restructuring alternatives could Motorola have pursued to increase shareholder value? Why do you believe it pursued this breakup strategy rather than some other option?

Motorola (Beginning 2010) Motorola (Mid-2010) Motorola (Beginning 2011) Mobility Devices Mobility Devices Motorola Mobility spin-off Enterprise Mobility Solutions \& Wireless Networks Enterprise Mobility Solutions* Motorola Inc. renamed Motorola Solutions

Kraft Foods Undertakes Split-Off of Post Cereals in Merger-Related Transaction

In August 2008, Kraft Foods announced an exchange offer related to the split-off of its Post Cereals unit and the closing of the merger of its Post Cereals business into a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ralcorp Holdings. Kraft is a major manufacturer and distributor of foods and beverages; Post is a leading manufacturer of breakfast cereals; and Ralcorp manufactures and distributes brand-name products in grocery and mass merchandise food outlets. The objective of the transaction was to allow Kraft shareholders participating in the exchange offer for Kraft Sub stock to become shareholders in Ralcorp and Kraft to receive almost $1 billion in cash or cash equivalents on a tax-free basis.

Prior to the transaction, Kraft borrowed $300 million from outside lenders and established Kraft Sub, a shell corporation wholly owned by Kraft. Kraft subsequently transferred the Post assets and associated liabilities, along with the liability Kraft incurred in raising $300 million, to Kraft Sub in exchange for all of Kraft Sub’s stock and $660 million in debt securities issued by Kraft Sub to be paid to Kraft at the end of ten years. In effect, Post was conveyed to Kraft Sub in exchange for assuming Kraft’s $300 million liability, 100% of Kraft Sub’s stock, and Kraft Sub debt securities with a principal amount of $660 million. The consideration that Kraft received, consisting of the debt assumption by Kraft Sub, the debt securities from Kraft Sub, and the Kraft Sub stock, is considered tax free to Kraft, since it is viewed simply as an internal reorganization rather than a sale. Kraft later converted to cash the securities received from Kraft Sub by selling them to a consortium of banks.

In the related split-off transaction, Kraft shareholders had the option to exchange their shares of Kraft common stock for shares of Kraft Sub, which owned the assets and liabilities of Post. If Kraft was unable to exchange all of the Kraft Sub common shares, Kraft would distribute the remaining shares as a dividend (i.e., spin-off) on a pro rata basis to Kraft shareholders.

With the completion of the merger of Kraft Sub with Ralcorp Sub (a Ralcorp wholly-owned subsidiary), the common shares of Kraft Sub were exchanged for shares of Ralcorp stock on a one for one basis. Consequently, Kraft shareholders tendering their Kraft shares in the exchange offer owned 0.6606 of a share of Ralcorp stock for each Kraft share exchanged as part of the split-off.

Concurrent with the exchange offer, Kraft closed the merger of Post with Ralcorp. Kraft shareholders received Ralcorp stock valued at $1.6 billion, resulting in their owning 54% of the merged firm. By satisfying the Morris Trust tax code regulations, the transaction was tax free to Kraft shareholders. Ralcorp Sub was later merged into Ralcorp. As such, Ralcorp assumed the liabilities of Ralcorp Sub, including the $660 million owed to Kraft.

The purchase price for Post equaled $2.56 billion. This price consisted of $1.6 billion in Ralcorp stock received by Kraft shareholders and $960 million in cash equivalents received by Kraft. The $960 million included the assumption of the $300 million liability by Kraft Sub and the $660 million in debt securities received from Kraft Sub. The steps involved in the transaction are described

-What does the decision to split up the firm say about Kraft's decision to buy Cadbury in 2010?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (37)

(37)

USX Bows to Shareholder Pressure to Split Up the Company

As one of the first firms to issue tracking stocks in the mid-1980s, USX relented to ongoing shareholder pressure to divide the firm into two pieces. After experiencing a sharp "boom/bust" cycle throughout the 1970s, U.S. Steel had acquired Marathon Oil, a profitable oil and gas company, in 1982 in what was at the time the second largest merger in U.S. history. Marathon had shown steady growth in sales and earnings throughout the 1970s. USX Corp. was formed in 1986 as the holding company for both U.S. Steel and Marathon Oil. In 1991, USX issued its tracking stocks to create "pure plays" in its primary businesses-steel and oil-and to utilize USX's steel losses, which could be used to reduce Marathon's taxable income. Marathon shareholders have long complained that Marathon's stock was selling at a discount to its peers because of its association with USX. The campaign to split Marathon from U.S. Steel began in earnest in early 2000.

On April 25, 2001, USX announced its intention to split U.S. Steel and Marathon Oil into two separately traded companies. The breakup gives holders of Marathon Oil stock an opportunity to participate in the ongoing consolidation within the global oil and gas industry. Holders of USX-U.S. Steel Group common stock (target stock) would become holders of newly formed Pittsburgh-based United States Steel Corporation, a return to the original name of the firm formed in 1901. Under the reorganization plan, U.S. Steel and Marathon would retain the same assets and liabilities already associated with each business. However, Marathon will assume $900 million in debt from U.S. Steel, leaving the steelmaker with $1.3 billion of debt. This assumption of debt by Marathon is an attempt to make U.S. Steel, which continued to lose money until 2004, able to stand on its own financially.

The investor community expressed mixed reactions, believing that Marathon would be likely to benefit from a possible takeover attempt, whereas U.S. Steel would not fare as well. Despite the initial investor pessimism, investors in both Marathon and U.S. Steel saw their shares appreciate significantly in the years immediately following the breakup.:

-Why do you believe USX shareholders were not content to continue to hold tracking stocks in Marathon Oil and U.S.

Steel?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (39)

(39)

The Warner Music Group is Sold at Auction

In selling a business, a firm may choose either to negotiate with a single potential buyer, to control the number of potential bidders, or to engage in a public auction.

The auction process often is viewed as the most effective way to get the highest price for a business to be sold; however, far from simple, an auction can be both a chaotic and a time-consuming procedure.

Auctions may be most suitable for businesses whose value is largely intangible or for “hard-to-value” businesses.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

In early 2011, the Warner Music Group (WMG), the third largest of the “big four” recorded-music companies, consisted of two separate businesses: one showing high growth potential and the other with declining revenues. Of WMG’s $3 billion in annual revenue, 82% came from sales of recorded music, with the remainder attributed to royalty payments for the use of music owned by the firm. Of the two, only recorded music has suffered revenue declines, due to piracy, aggressive pricing of online music sales, and the bankruptcy of many record retailers and wholesalers. In contrast, music publishing has grown as a result of diverse revenue streams from radio, television, advertising, and other sources. Music publishing also is benefiting from digital music downloads and the proliferation of cellphone ringtones.

In 2004, Warner Music’s parent at the time, Time Warner Inc., agreed to sell the business to a consortium led by THL Partners for $2.6 billion in cash. The group also included Edward Bronfman, Jr. (the Seagram’s heir, who also became the CEO of WMG), Bain Capital, and Providence Equity Partners. Having held the firm for seven years, a long time for private equity investors, its primary investors were seeking a way to cash out of the business, whose long-term fortunes appeared problematic. WMG’s investors were also in a race with Terra Firma Capital Partners, owner of the venerable British record company EMI, which was expected to take EMI public or to sell the business to a strategic buyer. WMG’s investors were concerned that, if EMI were to be sold before WMG, the firm’s exit strategy would be compromised, because there was much speculation that the only logical buyer for WMG was EMI.

By the end of January 2011, WMG had solicited about 70 potential bidders and attracted unsolicited indications of interest from at least 20 others. As this group winnowed through the auction’s three rounds, alliances among the bidders continually changed. In the ensuing auction, WMG’s stock price jumped by 75% from $4.72 per share on January 20 to $8.25 per share, for a total market value of $3.3 billion on May 6, 2011.

In view of the differences between these two businesses, WMG was open to selling the firm in total or in pieces, contributing to the extensive bidder interest. Risk takers were betting on an eventual recovery in recorded-music sales, while risk-averse investors were more likely to focus on music publishing. Prior to the auction, WMG distributed confidentiality agreements to 37 suitors, with 10 actually submitting a preliminary bid by the deadline of February 22, 2011. Of the preliminary bids, four were for the entire company, three for recorded music, and three for music publishing. For the entire firm, prices ranged from a low bid of $6 per share to a high bid of $8.25 per share. For recorded music, bids ranged from a low of $700 million to a high of $1.1 billion. Music publishing bids were almost twice that of recorded music, ranging from a low of $1.45 billion to a high of $2 billion.

For bidders, the objective is to make it to the next round in the auction; for sellers, the objective is less about prices offered during the initial round and more about determining who is committed to the process and who has the financial wherewithal to consummate the deal. According to the firm’s proxy pertaining to the sale, released on May 20, 2011, the subsequent bidding was characterized as a series of ever-changing alliances among bidders, with Access Industries submitting the winning bid. The sale appears to have been a success from the investors’ standpoint, with some speculating that THL alone earned an internal rate of return (including dividends) of 34%.

Motorola Bows to Activist Pressure

Under pressure from activist investor Carl Icahn, Motorola felt compelled to make a dramatic move before its May 2008 shareholders' meeting. Icahn had submitted a slate of four directors to replace those up for reelection and demanded that the wireless handset and network manufacturer take actions to improve profitability. Shares of Motorola, which had a market value of $22 billion, had fallen more than 60% since October 2006, making the firm’s board vulnerable in the proxy contest over director reelections.

Signaling its willingness to take dramatic action, Motorola announced on March 26, 2008, its intention to create two independent, publicly traded companies. The two new companies would consist of the firm's former Mobile Devices operation (including its Home Devices businesses consisting of modems and set-top boxes) and its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business. In addition to the planned spin-off, Motorola agreed to nominate two people supported by Carl Icahn to the firm’s board. Originally scheduled for 2009, the breakup was postponed due to the upheaval in the financial markets that year. The breakup would result in a tax-free distribution to Motorola's shareholders, with shareholders receiving shares of the two independent and publicly traded firms.

The Mobile Devices business designs, manufactures, and sells mobile handsets globally, and it has lost more than $5 billion during the last three years. The Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Networks business manufactures, designs, and services public safety radios, handheld scanners and telecommunications network gear for businesses and government agencies and generates nearly all of the Motorola’s current cash flow. This business also makes network equipment for wireless carriers such as Spring Nextel and Verizon Wireless.

By dividing the company in this manner, Motorola would separate its loss-generating Mobility Devices division from its other businesses. Although the third largest handset manufacturer globally, the handset business had been losing market share to Nokia and Samsung Electronics for years. Following the breakup, the Mobility Devices unit would be renamed Motorola Mobility, and the Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Networks operation would be called Motorola Solutions.

Motorola’s board is seeking to ensure the financial viability of Motorola Mobility by eliminating its outstanding debt and through a cash infusion. To do so, Motorola intends to buy back nearly all of its outstanding $3.9 billion debt and to transfer as much as $4 billion in cash to Motorola Mobility. Furthermore, Motorola Solutions would assume responsibility for the pension obligations of Motorola Mobility. If Motorola Mobility were to be forced into bankruptcy shortly after the breakup, Motorola Solutions may be held legally responsible for some of the business’s liabilities. The court would have to prove that Motorola had conveyed the Mobility Devices unit (renamed Motorola Mobility following the breakup) to its shareholders, fraudulently knowing that the unit’s financial viability was problematic.

Once free of debt and other obligations and flush with cash, Motorola Mobility would be in a better position to make acquisitions and to develop new phones. It would also be more attractive as a takeover target. A stand-alone firm is unencumbered by intercompany relationships, including such things as administrative support or parts and services supplied by other areas of Motorola. Moreover, all liabilities and assets associated with the handset business already would have been identified, making it easier for a potential partner to value the business.

In mid-2010, Motorola Inc. announced that it had reached an agreement with Nokia Siemens Networks, a Finnish-German joint venture, to buy the wireless networks operations, formerly part of its Enterprise Mobility Solutions & Wireless Network Devices business for $1.2 billion. On January 4, 2011, Motorola Inc. spun off the common shares of Motorola Mobility it held as a tax-free dividend to its shareholders and renamed the firm Motorola Solutions. Each shareholder of record as of December 21, 2010, would receive one share of Motorola Mobility common for every eight shares of Motorola Inc. common stock they held. Table 15.3 shows the timeline of Motorola’s restructuring effort.

Discussion Questions

1. In your judgment, did the breakup of Motorola make sense? Explain your answer.

2. What other restructuring alternatives could Motorola have pursued to increase shareholder value? Why do you believe it pursued this breakup strategy rather than some other option?

Motorola (Beginning 2010) Motorola (Mid-2010) Motorola (Beginning 2011) Mobility Devices Mobility Devices Motorola Mobility spin-off Enterprise Mobility Solutions \& Wireless Networks Enterprise Mobility Solutions* Motorola Inc. renamed Motorola Solutions

Kraft Foods Undertakes Split-Off of Post Cereals in Merger-Related Transaction

In August 2008, Kraft Foods announced an exchange offer related to the split-off of its Post Cereals unit and the closing of the merger of its Post Cereals business into a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ralcorp Holdings. Kraft is a major manufacturer and distributor of foods and beverages; Post is a leading manufacturer of breakfast cereals; and Ralcorp manufactures and distributes brand-name products in grocery and mass merchandise food outlets. The objective of the transaction was to allow Kraft shareholders participating in the exchange offer for Kraft Sub stock to become shareholders in Ralcorp and Kraft to receive almost $1 billion in cash or cash equivalents on a tax-free basis.

Prior to the transaction, Kraft borrowed $300 million from outside lenders and established Kraft Sub, a shell corporation wholly owned by Kraft. Kraft subsequently transferred the Post assets and associated liabilities, along with the liability Kraft incurred in raising $300 million, to Kraft Sub in exchange for all of Kraft Sub’s stock and $660 million in debt securities issued by Kraft Sub to be paid to Kraft at the end of ten years. In effect, Post was conveyed to Kraft Sub in exchange for assuming Kraft’s $300 million liability, 100% of Kraft Sub’s stock, and Kraft Sub debt securities with a principal amount of $660 million. The consideration that Kraft received, consisting of the debt assumption by Kraft Sub, the debt securities from Kraft Sub, and the Kraft Sub stock, is considered tax free to Kraft, since it is viewed simply as an internal reorganization rather than a sale. Kraft later converted to cash the securities received from Kraft Sub by selling them to a consortium of banks.

In the related split-off transaction, Kraft shareholders had the option to exchange their shares of Kraft common stock for shares of Kraft Sub, which owned the assets and liabilities of Post. If Kraft was unable to exchange all of the Kraft Sub common shares, Kraft would distribute the remaining shares as a dividend (i.e., spin-off) on a pro rata basis to Kraft shareholders.

With the completion of the merger of Kraft Sub with Ralcorp Sub (a Ralcorp wholly-owned subsidiary), the common shares of Kraft Sub were exchanged for shares of Ralcorp stock on a one for one basis. Consequently, Kraft shareholders tendering their Kraft shares in the exchange offer owned 0.6606 of a share of Ralcorp stock for each Kraft share exchanged as part of the split-off.

Concurrent with the exchange offer, Kraft closed the merger of Post with Ralcorp. Kraft shareholders received Ralcorp stock valued at $1.6 billion, resulting in their owning 54% of the merged firm. By satisfying the Morris Trust tax code regulations, the transaction was tax free to Kraft shareholders. Ralcorp Sub was later merged into Ralcorp. As such, Ralcorp assumed the liabilities of Ralcorp Sub, including the $660 million owed to Kraft.

The purchase price for Post equaled $2.56 billion. This price consisted of $1.6 billion in Ralcorp stock received by Kraft shareholders and $960 million in cash equivalents received by Kraft. The $960 million included the assumption of the $300 million liability by Kraft Sub and the $660 million in debt securities received from Kraft Sub. The steps involved in the transaction are described

-Why did Kraft chose not to divest its grocery business, using the proceeds to either reinvest in its faster growing snack business, to buy back its stock, or a combination of the two?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (31)

(31)

Tracking stocks are often created to give investors a pure play investment opportunity in one of the parent's subsidiaries.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

Hewlett Packard (HP) announced the spin-off of its Agilent Technologies unit to focus on its main business of computers and printers, where sales have been lagging behind such competitors as Sun Microsystems. Agilent makes test, measurement, and monitoring instruments; semiconductors; and optical components. It also supplies patient-monitoring and ultrasound-imaging equipment to the health care industry. HP will retain an 85% stake in the company. The cash raised through the 15% equity carve-out will be paid to HP as a dividend from the subsidiary to the parent. Hewlett Packard will provide Agilent with $983 million in start-up funding. HP retained a controlling interest until mid-2000, when it spun-off the rest of its shares in Agilent to HP shareholders as a tax-free transaction.

-Discuss the reasons why HP may have chosen a staged transaction rather than an outright divestiture of the business.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (38)

(38)

Acquiring companies often find themselves with certain assets and operations of the acquired company that do not fit their primary strategy. Such assets may be divested to fund future investments.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

The divesting firm is required to recognize a gain or loss for financial reporting purposes equal to the difference between the fair value of the consideration received for the divested operation and its market value.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (40)

(40)

Hughes Corporation's Dramatic Transformation

In one of the most dramatic redirections of corporate strategy in U.S. history, Hughes Corporation transformed itself from a defense industry behemoth into the world's largest digital information and communications company. Once California's largest manufacturing employer, Hughes Corporation built spacecraft, the world's first working laser, communications satellites, radar systems, and military weapons systems. However, by the late 1990s, the firm had undergone substantial gut-wrenching change to reposition the firm in what was viewed as a more attractive growth opportunity. This transformation culminated in the firm being acquired in 2004 by News Corp., a global media empire.

To accomplish this transformation, Hughes divested its communications satellite businesses and its auto electronics operation. The corporate overhaul created a firm focused on direct-to-home satellite broadcasting with its DirecTV service offering. DirecTV's introduction to nearly 12 million U.S. homes was a technology made possible by U.S. military spending during the early 1980s. Although military spending had fueled much of Hughes' growth during the decade of the 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear by 1988 that the level of defense spending of the Reagan years was coming to a close with the winding down of the cold war.

For the next several years, Hughes attempted to find profitable niches in the rapidly consolidating U.S. defense contracting industry. Hughes acquired General Dynamics' missile business and made 15 smaller defense-related acquisitions. Eventually, Hughes' parent firm, General Motors, lost enthusiasm for additional investment in defense-related businesses. GM decided that, if Hughes could not participate in the shrinking defense industry, there was no reason to retain any interests in the industry at all. In November 1995, Hughes initiated discussions with Raytheon, and two years later, it sold its aerospace and defense business to Raytheon for $9.8 billion. The firm also merged its Delco product line with GM's Delphi automotive systems. What remained was the firm's telecommunications division. Hughes had transformed itself from a $16 billion defense contractor to a svelte $4 billion telecommunications business.

Hughes' telecommunications unit was its smallest operation but, with DirecTV, its fastest growing. The transformation was to exact a huge cultural toll on Hughes' employees, most of whom had spent their careers dealing with the U.S. Department of Defense. Hughes moved to hire people aggressively from the cable and broadcast businesses. By the late 1990s, former Hughes' employees constituted only 15-20 percent of DirecTV's total employees.

Restructuring continued through the end of the 1990s. In 2000, Hughes sold its satellite manufacturing operations to Boeing for $3.75 billion. This eliminated the last component of the old Hughes and cut its workforce in half. In December 2000, Hughes paid about $180 million for Telocity, a firm that provides digital subscriber line service through phone lines. This acquisition allowed Hughes to provide high-speed Internet connections through its existing satellite service, mainly in more remote rural areas, as well as phone lines targeted at city dwellers. Hughes now could market the same combination of high-speed Internet services and video offered by cable providers, Hughes' primary competitor.

In need of cash, GM put Hughes up for sale in late 2000, expressing confidence that there would be a flood of lucrative offers. However, the faltering economy and stock market resulted in GM receiving only one serious bid, from media tycoon Rupert Murdoch of News Corp. in February 2001. But, internal discord within Hughes and GM over the possible buyer of Hughes Electronics caused GM to backpedal and seek alternative bidders. In late October 2001, GM agreed to sell its Hughes Electronics subsidiary and its DirecTV home satellite network to EchoStar Communication for $25.8 billion. However, regulators concerned about the antitrust implications of the deal disallowed this transaction. In early 2004, News Corp., General Motors, and Hughes reached a definitive agreement in which News Corp acquired GM's 19.9 percent stake in Hughes and an additional 14.1 percent of Hughes from public shareholders and GM's pension and other benefit plans. News Corp. paid about $14 per share, making the deal worth about $6.6 billion for 34.1 percent of Hughes. The implied value of 100 percent of Hughes was, at that time, $19.4 billion, about three fourths of EchoStar's valuation three years earlier.

-Why did Hughes' board and management seem to rely heavily on divestitures rather than other restructuring

strategies discussed in this chapter to achieve the radical transformation of the firm? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (45)

(45)

Anatomy of a Spin-Off

On October 18, 2006, Verizon Communication's board of directors declared a dividend to the firm's shareholders consisting of shares in a company comprising the firm's domestic print and Internet yellow pages directories publishing operations (Idearc Inc.). The dividend consisted of 1 share of Idearc stock for every 20 shares of Verizon common stock. Idearc shares were valued at $34.47 per share. On the dividend payment date, Verizon shares were valued at $36.42 per share. The 1-to-20 ratio constituted a 4.73% yield—that is, $34.47/ ($36.42 × 20)—approximately equal to Verizon's then current cash dividend yield.

Because of the spin-off, Verizon would contribute to Idearc all its ownership interest in Idearc Information Services and other assets, liabilities, businesses, and employees currently employed in these operations. In exchange for the contribution, Idearc would issue to Verizon shares of Idearc common stock to be distributed to Verizon shareholders. In addition, Idearc would issue senior unsecured notes to Verizon in an amount approximately equal to the $9 billion in debt that Verizon incurred in financing Idearc's operations historically. Idearc would also transfer $2.5 billion in excess cash to Verizon. Verizon believed it owned such cash balances, since they were generated while Idearc was part of the parent.

Verizon announced that the spin-off would enable the parent and Idearc to focus on their core businesses, which may facilitate expansion and growth of each firm. The spin-off would also allow each company to determine its own capital structure, enable Idearc to pursue an acquisition strategy using its own stock, and permit Idearc to enhance its equity-based compensation programs offered to its employees. Because of the spin-off, Idearc would become an independent public company. Moreover, no vote of Verizon shareholders was required to approve the spin-off, since it constitutes the payment of a dividend permissible by the board of directors according to the bylaws of the firm. Finally, Verizon shareholders have no appraisal rights in connection with the spin-off.

In late 2009, Idearc entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy because it was unable to meet its outstanding debt obligations. In September 2010, a trustee for Idearc’s creditors filed a lawsuit against Verizon, alleging that the firm breached its fiduciary responsibility by knowingly spinning off a business that was not financially viable. The lawsuit further contends that Verizon benefitted from the spin-off at the expense of the creditors by transferring $9 billion in debt from its books to Idearc and receiving $2.5 billion in cash from Idearc.

-How do you believe the Idearc shares were valued for purposes of the spin-off? Be specific

(Short Answer)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

Showing 81 - 100 of 152

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)