Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies

Exam 1: Introduction to Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities139 Questions

Exam 2: The Regulatory Environment129 Questions

Exam 3: The Corporate Takeover Market:152 Questions

Exam 4: Planning: Developing Business and Acquisition Plans: Phases 1 and 2 of the Acquisition Process137 Questions

Exam 5: Implementation: Search Through Closing: Phases 310 of the Acquisition Process131 Questions

Exam 6: Postclosing Integration: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Business Alliances138 Questions

Exam 7: Merger and Acquisition Cash Flow Valuation Basics108 Questions

Exam 8: Relative, Asset-Oriented, and Real Option109 Questions

Exam 9: Financial Modeling Basics:97 Questions

Exam 10: Analysis and Valuation127 Questions

Exam 11: Structuring the Deal:138 Questions

Exam 12: Structuring the Deal:125 Questions

Exam 13: Financing the Deal149 Questions

Exam 14: Applying Financial Modeling116 Questions

Exam 15: Business Alliances: Joint Ventures, Partnerships, Strategic Alliances, and Licensing138 Questions

Exam 16: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies152 Questions

Exam 17: Alternative Exit and Restructuring Strategies:118 Questions

Exam 18: Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:120 Questions

Select questions type

A split-up involves carving out a portion of the equity of each of the parent's operating subsidiaries and selling the shares to the public.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (35)

(35)

In a public solicitation, a firm can announce publicly that it is putting itself, a subsidiary, or a product line up for sale. Either potential buyers contact the seller or the seller actively solicits bids from potential buyers or both.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (39)

(39)

The reasons for selecting a divestiture, carve-out, or spin-off strategy are basically the same.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (36)

(36)

Viacom to Spin Off Blockbuster

After months of trying to sell its 81% stake in Blockbuster Inc. undertook a tax-free spin-off in mid 2004. Viacom shareholders will have the option to swap their Viacom shares for Blockbuster shares and a special cash payout. Blockbuster had been hurt by competition from low-priced rivals and the erosion of video rentals by accelerating DVD sales. Despite Blockbuster's steady contribution to Viacom's overall cash flow, Viacom believed that the growth prospects for the unit were severely limited. In preparation for the spin-off, Viacom had reported a $1.3 billion charge to earnings in the fourth quarter of 2003 in writing down goodwill associated with its acquisition of Blockbuster. By spinning off Blockbuster, Viacom Chairman and ECO Sumner Redstone statd that the firm would now be able to focus on its core TV (i.e., CBS and MTV) and movie (i.e., Paramount Studios) businesses. Blockbuster shares fell by 4% and Viacom shares rose by 1% on the day of the announcement.

-In your opinion, why did Viacom and Blockbuster share prices react the way they did to the announcement of the spin-off?

(Essay)

4.7/5  (30)

(30)

Equity carve-outs are similar to divestitures and spin-offs in that they provide a cash infusion to the parent.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (42)

(42)

The Anatomy of a Spin-Off-Northrop Grumman Exits the Shipbuilding Business

There are many ways a firm can choose to separate itself from one of its operations.

Which restructuring method is used reflects the firm's objectives and circumstances.

______________________________________________________________________________

In an effort to focus on more attractive growth markets, Northrop Grumman Corporation (NGC), a global leader in aerospace, communications, defense, and security systems, announced that it would exit its mature shipbuilding business on October 15, 2010. Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), the largest military U.S. shipbuilder and a wholly owned subsidiary of NGC, had been under pressure to cut costs amidst increased competition from competitors such as General Dynamics and a slowdown in orders from the U.S. Navy. Nor did the outlook for the shipbuilding industry look like it would improve any time soon.

Given the limited synergy between shipbuilding and HII's other businesses, HII's operations were largely independent of NGC's other units. NGC's management and board argued that their decision to separate from the shipbuilding business would enable both NGC and HII to focus on those areas they knew best. Moreover, given the shipbuilding business's greater ongoing capital requirements, HII would find it easier to tap capital markets directly rather than to compete with other NGC operations for financing. Finally, investors would be better able to value businesses (NGC and HII) whose operations were more focused.

After reviewing a range of options, NGC pursued a spin-off as the most efficient way to separate itself from its shipbuilding operations. If properly structured, spin-offs are tax free to shareholders. Furthermore, management argued that they could be completed in a timelier manner and were less disruptive to current operations than an outright sale of the business. The spin-off represented about one-sixth of NGC's $36 billion in 2010 revenue. Effective March 31, 2011, all of the outstanding stock of HII was spun off to NGC shareholders through a pro rata distribution to shareholders of record on March 30, 2011. Each NGC shareholder received one HII common share for every six shares of NGC common stock held.

The share-exchange ratio of one share of HII common for each six shares of NGC common was calculated by dividing HII's 48.8 million common shares (having a par value of $.01) by the 298 million NGC shares outstanding. Since fractional shares were created, shareholders owning 100 shares would be entitled to 16.6667 shares-100/6. In this instance, the shareholder would receive 16 HII shares and the cash equivalent of 0.6667 shares. The cash to pay for fractional shares came from the aggregation of all fractional shares, which were subsequently sold in the public market. The cash proceeds were then distributed to NGC shareholders on a pro rata basis and were taxable to the extent a taxable gain is incurred by the shareholder.

The spin-off process involved an internal reorganization of NGC businesses, a Separation and Distribution Agreement, and finally the actual distribution of HII shares to NGC shareholders. The internal reorganization and subsequent spin-off is illustrated in Figure 16.4. NGC (referred to as Current Northrop Grumman Corporation) first reorganized its businesses such that the firm would become a holding company whose primary investments would include Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) and Northrop Grumman Systems Corporation (i.e., all other non-shipbuilding operations). HII was formed in anticipation of the spin-off as a holding company for NGC's shipbuilding business, which had been previously known as Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding (NGSB). NGSB was changed to Huntington Ingalls Industries Company following the spin-off. Reflecting the new organizational structure, Current Northrop Grumman common stock was exchanged for stock in New Northrop Grumman Corporation. This internal reorganization was followed by the distribution of HII stock to NGC's common shareholders.

Following the spin-off, HII became a separate company from NGC, with NGC having no ownership interest in HII. Renamed Titan II, Current NGC became a direct, wholly owned subsidiary of HII and held no material assets or liabilities other than Current NGC's guarantees of HII performance under certain HII shipbuilding contracts (under way prior to the spin-off and guaranteed by NGC) and HII's obligations to repay intercompany loans owed to NGC. New NGC changed its name to Northrop Grumman Corporation. The board of directors remained the same following the reorganization.

No gain or loss was incurred by common shareholders because the exchange of stock between the Current and New Northrop Grumman corporations did not change the shareholders' tax basis in the stock. Similarly, no gain or loss was incurred by shareholders with the distribution of HII's stock, since there was no change in the total value of their investment. That is, the value of the HII shares were offset by a corresponding reduction in the value of NGC shares, reflecting the loss of HII's cash flows.

Before the spin-off, HII entered into a Separation and Distribution Agreement with NGC that governed the relationship between HII and NGC after completion of the spin-off and provided for the allocation between the two firms of assets, liabilities, and obligations (e.g., employee benefits, intellectual property, information technology, insurance, and tax-related assets and liabilities). The agreement also provided that NGC and HII each would indemnify (compensate) the other against any liabilities arising out of their respective businesses. As part of the agreement, HII agreed not to engage in any transactions, such as mergers or acquisitions, involving share-for-share exchanges that would change the ownership of the firm by more than 50% for at least two years following the transaction. A change in control could violate the IRS's "continuity of interest" requirement and jeopardize the tax-free status of the spin-off. Consequently, HII put in place certain takeover defenses to make takeovers difficult.

-What is the likely impact of the spin-off on Northrop Grumman's share price immediately following the spin-off of Huntington Ingalls assuming no other factors offset it?

(Essay)

5.0/5  (40)

(40)

Bristol-Myers Squibb Splits Off Rest of Mead Johnson

Facing the loss of patent protection for its blockbuster drug Plavix, a blood thinner, in 2012, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company decided to split off its 83% ownership stake in Mead Johnson Nutrition Company in late 2009 through an offer to its shareholders to exchange their Bristol-Myers shares for Mead Johnson shares. The decision was part of a longer-term restructuring strategy that included the sale of assets to raise money for acquisitions of biotechnology drug companies and the elimination of jobs to reduce annual operating expenses by $2.5 billion by the end of 2012.

Bristol-Myers anticipated a significant decline in operating profit following the loss of patent protection as increased competition from lower-priced generics would force sizeable reductions in the price of Plavix. Furthermore, Bristol-Myers considered Mead Johnson, a baby formula manufacturer, as a noncore business that was pursuing a focus on biotechnology drugs. Bristol-Myers shareholders greeted the announcement positively, with the firm's shares showing the largest one-day increase in eight months.

In the exchange offer, Bristol-Myers shareholders were able to exchange some, none, or all of their shares of Bristol-Myers common stock for shares of Mead Johnson common stock at a discount. The discount was intended to provide an incentive for Bristol-Myers shareholders to tender their shares. Also, the rapid appreciation of the Mead Johnson shares in the months leading up to the announced split-off suggested that these shares could have attractive long-term appreciation potential.

While the transaction did not provide any cash directly to the firm, it did indirectly augment Bristol-Myer's operating cash flow by $214 million annually. This represented the difference between the $350 million that Bristol-Myers paid in dividends to Mead Johnson shareholders and the $136 million it received in dividends from Mead Johnson each year. By reducing the number of Bristol-Myers shares outstanding, the transaction also improved Bristol-Myers' earnings per share by 4% in 2011. Finally, by splitting-off a noncore business, Bristol-Myers was increasing its attractiveness to investors interested in a "pure play" in biotechnology pharmaceuticals.

The exchange was tax free to Bristol-Myers shareholders participating in the exchange offer, who also stood to gain if the now independent Mead Johnson Corporation were acquired at a later date. The newly independent Mead Johnson had a poison pill in place to discourage any takeover within six months to a year following the split-off. The tax-free status of the transaction could have been disallowed by the IRS if the transaction were viewed as a "disguised sale" intended to allow Bristol-Myers to avoid paying taxes on gains incurred if it had chosen to sell Mead Johnson.

British Petroleum Sells Oil and Gas Assets to Apache Corporation

In the months that followed the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, British Petroleum agreed to create a $20 billion fund to help cover the damages and cleanup costs associated with the spill. The firm had agreed to contribute $5 billion to the fund before the end of 2010. To help meet this obligation and to help finance the more than $4 billion already spent on the spill, the firm announced on July 20, 2010, that it had reached an agreement to sell Apache Corporation its oil and gas fields in Texas and southeast New Mexico worth $3.1 billion; gas fields in Western Canada for $3.25 billion; and oil and gas properties in Egypt for $650 million. All of these properties had been in production for years, and their output rates were declining.

Apache is a Houston, Texas-based independent oil and gas exploration firm with a reputation for being able to extract additional oil and gas from older properties. Also, Apache had operations near each of the BP properties, enabling them to take control of the acquired assets with existing personnel.

In what appears to have been a premature move, Apache agreed to acquire Mariner Energy and Devon Energy's offshore assets in the Gulf of Mexico for a total of $3.75 billion just days before the BP oil rig explosion in the Gulf. The acquisitions made Apache a major player in the Gulf just weeks before the United States banned temporarily deep-water drilling exploration in federal waters.

The announcement of the sale of these properties came as a surprise because BP had been rumored to be attempting to sell its stake in the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. The sale had been expected to fetch as much as $10 billion. The sale failed to materialize because of lingering concerns that BP might at some point seek bankruptcy protection and because the firm's creditors could seek to reverse an out-of-court asset sale as a fraudulent conveyance of assets. Fraudulent conveyance refers to the illegal transfer of assets to another party in order to defer, hinder, or defraud creditors. Under U.S. bankruptcy laws, courts might order that any asset sold by a company in distress, such as BP, must be encumbered with some of the liabilities of the seller if it can be shown that the distressed firm undertook the sale with the full knowledge that it would be filing for bankruptcy protection at a later date.

Ideally, buyers would like to purchase assets "free and clear" of the environmental liabilities associated with the Gulf oil spill. Consequently, a buyer of BP assets would have to incorporate such risks in determining the purchase price for such assets. In some instances, buyers will buy assets only after the seller has gone through the bankruptcy process in order to limit fraudulent conveyance risks.

-How could Apache have protected itself from risks that they might be required at some point in the future to be liable

for some portion of the BP Gulf-related liabilities? What are some of the ways Apache could have estimated the potential costs of such liabilities? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (34)

(34)

In general, a voluntary bust-up or liquidation has the advantage over mergers of deferring the recognition of a gain by the stockholders of the selling company until they eventually sell the stock.

(True/False)

4.9/5  (40)

(40)

For financial reporting purposes, a distribution of tracking stock splits the parent firm's equity structure into separate classes of stock without a legal split-up of the firm.

(True/False)

4.8/5  (44)

(44)

AT&T (1984 - 2005)-A POSTER CHILD

FOR RESTRUCTURING GONE AWRY

Between 1984 and 2000, AT&T underwent four major restructuring programs. These included the government-mandated breakup in 1984, the 1996 effort to eliminate customer conflicts, the 1998 plan to become a broadband powerhouse, and the most recent restructuring program announced in 2000 to correct past mistakes. It is difficult to identify another major corporation that has undergone as much sustained trauma as AT&T. Ironically, a former AT&T operating unit acquired its former parent in 2005.

The 1984 Restructure: Changed the Organization But Not the Culture

The genesis of Ma Bell's problems may have begun with the consent decree signed with the Department of Justice in 1984, which resulted in the spin-off of its local telephone operations to its shareholders. AT&T retained its long-distance and telecommunications equipment manufacturing operations. Although the breadth of the firm's product offering changed dramatically, little else seems to have changed. The firm remained highly bureaucratic, risk averse, and inward looking. However, substantial market share in the lucrative long-distance market continued to generate huge cash flow for the company, thereby enabling the company to be slow to react to the changing competitive dynamics of the marketplace.

The 1996 Restructure: Lack of a Coherent Strategy

Cash accumulated from the long-distance business was spent on a variety of ill-conceived strategies such as the firm's foray into the personal computer business. After years of unsuccessfully attempting to redefine the company's strategy, AT&T once again resorted to a major restructure of the firm. In 1996, AT&T spun-off Lucent Technologies (its telecommunications equipment business) and NCR (a computer services business) to shareholders to facilitate Lucent equipment sales to former AT&T operations and to eliminate the non-core NCR computer business. However, this had little impact on the AT&T share price.

The 1998 Restructure: Vision Exceeds Ability to Execute

In its third major restructure since 1984, AT&T CEO Michael Armstrong passionately unveiled in June of 1998 a daring strategy to transform AT&T from a struggling long-distance telephone company into a broadband internet access and local phone services company. To accomplish this end, he outlined his intentions to acquire cable companies MediaOne Group and Telecommunications Inc. for $58 billion and $48 billion, respectively. The plan was to use cable-TV networks to deliver the first fully integrated package of broadband internet access and local phone service via the cable-TV network.

AT&T Could Not Handle Its Early Success

During the next several years, Armstrong seemed to be up to the task, cutting sales, general, and administrative expense's share of revenue from 28 percent to 20 percent, giving AT&T a cost structure comparable to its competitors. He attempted to change the bureaucratic culture to one able to compete effectively in the deregulated environment of the post-1996 Telecommunications Act by issuing stock options to all employees, tying compensation to performance, and reducing layers of managers. He used AT&T's stock, as well as cash, to buy the cable companies before the decline in AT&T's long-distance business pushed the stock into a free fall. He also transformed AT&T Wireless from a collection of local businesses into a national business.

Notwithstanding these achievements, AT&T experienced major missteps. Employee turnover became a big problem, especially among senior managers. Armstrong also bought Telecommunications and MediaOne when valuations for cable-television assets were near their peak. He paid about $106 billion in 2000, when they were worth about $80 billion. His failure to cut enough deals with other cable operators (e.g., Time Warner) to sell AT&T's local phone service meant that AT&T could market its services only in regional markets rather than on a national basis. In addition, AT&T moved large corporate customers to its Concert joint venture with British Telecom, alienating many AT&T salespeople, who subsequently quit. As a result, customer service deteriorated rapidly and major customers defected. Finally, Armstrong seriously underestimated the pace of erosion in AT&T's long-distance revenue base.

AT&T May Have Become Overwhelmed by the Rate of Change

What happened? Perhaps AT&T fell victim to the same problems many other acquisitive companies have. AT&T is a company capable of exceptional vision but incapable of effective execution. Effective execution involves buying or building assets at a reasonable cost. Its substantial overpayment for its cable acquisitions meant that it would be unable to earn the returns required by investors in what they would consider a reasonable period. Moreover, Armstrong's efforts to shift from the firm's historical business by buying into the cable-TV business through acquisition had saddled the firm with $62 billion in debt.

AT&T tried to do too much too quickly. New initiatives such as high-speed internet access and local telephone services over cable-television network were too small to pick up the slack. Much time and energy seems to have gone into planning and acquiring what were viewed as key building blocks to the strategy. However, there appears to have been insufficient focus and realism in terms of the time and resources required to make all the pieces of the strategy fit together. Some parts of the overall strategy were at odds with other parts. For example, AT&T undercut its core long-distance wired telephone business by offers of free long-distance wireless to attract new subscribers. Despite aggressive efforts to change the culture, AT&T continued to suffer from a culture that evolved in the years before 1996 during which the industry was heavily regulated. That atmosphere bred a culture based on consensus building, ponderously slow decision-making, and a low tolerance for risk. Consequently, the AT&T culture was unprepared for the fiercely competitive deregulated environment of the late 1990s (Truitt, 2001).

Furthermore, AT&T created individual tracking stocks for AT&T Wireless and for Liberty Media. The intention of the tracking stocks was to link the unit's stock to its individual performance, create a currency for the unit to make acquisitions, and to provide a new means of motivating the unit's management by giving them stock in their own operation. Unlike a spin-off, AT&T's board continued to exert direct control over these units. In an IPO in April 2000, AT&T sold 14 percent of AT&T's Wireless tracking stock to the public to raise funds and to focus investor attention on the true value of the Wireless operations.

Investors Lose Patience

Although all of these actions created a sense that grandiose change was imminent, investor patience was wearing thin. Profitability foundered. The market share loss in its long-distance business accelerated. Although cash flow remained strong, it was clear that a cash machine so dependent on the deteriorating long-distance telephone business soon could grind to a halt. Investors' loss of faith was manifested in the sharp decline in AT&T stock that occurred in 2000.

The 2000 Restructure: Correcting the Mistakes of the Past

Pushed by investor impatience and a growing realization that achieving AT&T's vision would be more time and resource consuming than originally believed, Armstrong announced on October 25, 2000 the breakup of the business for the fourth time. The plan involved the creation of four new independent companies including AT&T Wireless, AT&T Consumer, AT&T Broadband, and Liberty Media.

By breaking the company into specific segments, AT&T believed that individual units could operate more efficiently and aggressively. AT&T's consumer long-distance business would be able to enter the digital subscriber line (DSL) market. DSL is a broadband technology based on the telephone wires that connect individual homes with the telephone network. AT&T's cable operations could continue to sell their own fast internet connections and compete directly against AT&T's long-distance telephone business. Moreover, the four individual businesses would create "pure-play" investor opportunities. Specifically, AT&T proposed splitting off in early 2001 AT&T Wireless and issuing tracking stocks to the public in late 2001 for AT&T's Consumer operations, including long-distance and Worldnet Internet service, and AT&T's Broadband (cable) operations. The tracking shares would later be converted to regular AT&T common shares as if issued by AT&T Broadband, making it an independent entity. AT&T would retain AT&T Business Services (i.e., AT&T Lab and Telecommunications Network) with the surviving AT&T entity. Investor reaction was swift and negative. Not swayed by the proposal, investors caused the stock to drop 13 percent in a single day. Moreover, it ended 2000 at 17 ½, down 66 percent from the beginning of the year.

The More Things Change The More They Stay The Same

On July 10, 2001, AT&T Wireless Services became an independent company, in accordance with plans announced during the 2000 restructure program. AT&T Wireless became a separate company when AT&T converted the tracking shares of the mobile-phone business into common stock and split-off the unit from the parent. AT&T encouraged shareholders to exchange their AT&T common shares for Wireless common shares by offering AT&T shareholders 1.176 Wireless shares for each share of AT&T common. The exchange ratio represented a 6.5 percent premium over AT&T's current common share price. AT&T Wireless shares have fallen 44 percent since AT&T first sold the tracking stock in April 2000. On August 10, 2001, AT&T spun off Liberty Media.

After extended discussions, AT&T agreed on December 21, 2001 to merge its broadband unit with Comcast to create the largest cable television and high-speed internet service company in the United States. Without the future growth engine offered by Broadband and Wireless, AT&T's remaining long-distance businesses and business services operations had limited growth prospects. After a decade of tumultuous change, AT&T was back where it was at the beginning of the 1990s. At about $15 billion in late 2004, AT&T's market capitalization was about one-sixth of that of such major competitors as Verizon and SBC. SBC Communications (a former local AT&T operating company) acquired AT&T on November 18, 2005 in a $16 billion deal and promptly renamed the combined firms AT&T.

-To what extent did AT&T's ineffectual restructuring reflect factors beyond their control and to what extent was it poor implementation?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (38)

(38)

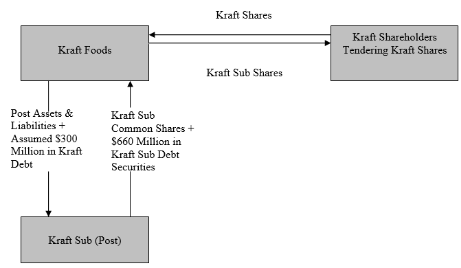

Step 1: Kraft creates a shell subsidiary (Kraft Sub) and transfers Post assets and liabilities and $300 million in Kraft debt into the shell in exchange for Kraft Sub stock plus $660 million in Kraft Sub debt securities. Kraft also implements an exchange offer of Kraft Sub for Kraft common stock.

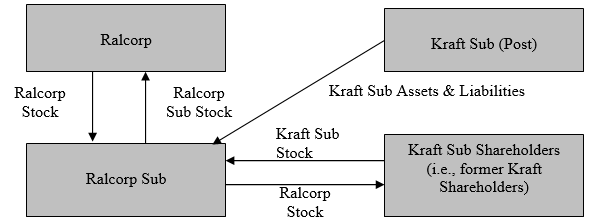

Step 2: Kraft Sub, as an independent company, is merged in a forward triangular tax-free merger with a sub of Ralcorp (Ralcorp Sub) in which Kraft Sub shares are exchanged for Ralcorp shares, with Ralcorp Sub surviving.

Step 2: Kraft Sub, as an independent company, is merged in a forward triangular tax-free merger with a sub of Ralcorp (Ralcorp Sub) in which Kraft Sub shares are exchanged for Ralcorp shares, with Ralcorp Sub surviving.

Sara Lee Attempts to Create Value through Restructuring

After spurning a series of takeover offers, Sara Lee, a global consumer goods company, announced in early 2011 its intention to split the firm into two separate publicly traded companies. The two companies would consist of the firm’s North American retail and food service division and its international beverage business. The announcement comes after a long string of restructuring efforts designed to increase shareholder value. It remains to be seen if the latest effort will be any more successful than earlier efforts.

Reflecting a flawed business strategy, Sara Lee had struggled for more than a decade to create value for its shareholders by radically restructuring its portfolio of businesses. The firm’s business strategy had evolved from one designed in the mid-1980s to market a broad array of consumer products from baked goods to coffee to underwear under the highly recognizable brand name of Sara Lee into one that was designed to refocus the firm on the faster-growing food and beverage and apparel businesses. Despite acquiring several European manufacturers of processed meats in the early 1990s, the company’s profits and share price continued to flounder.

In September 1997, Sara Lee embarked on a major restructuring effort designed to boost both profits, which had been growing by about 6% during the previous five years, and the company’s lagging share price. The restructuring program was intended to reduce the firm’s degree of vertical integration, shifting from a manufacturing and sales orientation to one focused on marketing the firm’s top brands. The firm increasingly viewed itself as more of a marketing than a manufacturing enterprise.

Sara Lee outsourced or sold 110 manufacturing and distribution facilities over the next two years. Nearly 10,000 employees, representing 7% of the workforce, were laid off. The proceeds from the sale of facilities and the cost savings from outsourcing were either reinvested in the firm’s core food businesses or used to repurchase $3 billion in company stock. 1n 1999 and 2000, the firm acquired several brands in an effort to bolster its core coffee operations, including such names as Chock Full o’Nuts, Hills Bros, and Chase & Sanborn.

Despite these restructuring efforts, the firm’s stock price continued to drift lower. In an attempt to reverse the firm’s misfortunes, the firm announced an even more ambitious restructuring plan in 2000. Sara Lee would focus on three main areas: food and beverages, underwear, and household products. The restructuring efforts resulted in the shutdown of a number of meat packing plants and a number of small divestitures, resulting in a 10% reduction (about 13,000 people) in the firm’s workforce. Sara Lee also completed the largest acquisition in its history, purchasing The Earthgrains Company for $1.9 billion plus the assumption of $0.9 billion in debt. With annual revenue of $2.6 billion, Earthgrains specialized in fresh packaged bread and refrigerated dough. However, despite ongoing restructuring activities, Sara Lee continued to underperform the broader stock market indices.

In February 2005, Sara Lee executed its most ambitious plan to transform the firm into a company focused on the global food, beverage, and household and body care businesses. To this end, the firm announced plans to dispose of 40% of its revenues, totaling more than $8 billion, including its apparel, European packaged meats, U.S. retail coffee, and direct sales businesses.

In 2006, the firm announced that it had completed the sale of its branded apparel business in Europe, Global Body Care and European Detergents units, and its European meat processing operations. Furthermore, the firm spun off its U.S. Branded Apparel unit into a separate publicly traded firm called HanesBrands Inc. The firm raised more than $3.7 billion in cash from the divestitures. The firm was now focused on its core businesses: food, beverages, and household and body care.

In late 2008, Sara Lee announced that it would close its kosher meat processing business and sold its retail coffee business. In 2009, the firm sold its Household and Body Care business to Unilever for $1.6 billion and its hair care business to Procter & Gamble for $0.4 billion.

In 2010, the proceeds of the divestitures made the prior year were used to repurchase $1.3 billion of Sara Lee’s outstanding shares. The firm also announced its intention to repurchase another $3 billion of its shares during the next three years. If completed, this would amount to about one-third of its approximate $10 billion market capitalization at the end of 2010.

What remains of the firm are food brands in North America, including Hillshire Farm, Ball Park, and Jimmy Dean processed meats and Sara Lee baked goods and Earthgrains. A food distribution unit will also remain in North America, as will its beverage and bakery operations. Sara Lee is rapidly moving to become a food, beverage, and bakery firm. As it becomes more focused, it could become a takeover target.

Has the 2005 restructuring program worked? To answer this question, it is necessary to determine the percentage change in Sara Lee’s share price from the announcement date of the restructuring program to the end of 2010, as well as the percentage change in the share price of HanesBrands Inc., which was spun off on August 18, 2006. Sara Lee shareholders of record received one share of HanesBrands Inc. for every eight Sara Lee shares they held.

Sara Lee’s share price jumped by 6% on the February 21, 2004 announcement date, closing at $19.56. Six years later, the stock price ended 2010 at $14.90, an approximate 24% decline since the announcement of the restructuring program in early 2005. Immediately following the spinoff, HanesBrands’ stock traded at $22.06 per share; at the end of 2010, the stock traded at $25.99, a 17.8% increase.

A shareholder owning 100 Sara Lee shares when the spin-off was announced would have been entitled to 12.5 HanesBrands shares. However, they would have actually received 12 shares plus $11.03 for fractional shares (i.e., 0.5 × $22.06).

A shareholder of record who had 100 Sara Lee shares on the announcement date of the restructuring program and held their shares until the end of 2010 would have seen their investment decline 24% from $1,956 (100 shares × $19.56 per share) to $1,486.56 by the end of 2010. However, this would have been partially offset by the appreciation of the HanesBrands shares between 2006 and 2010. Therefore, the total value of the hypothetical shareholder’s investment would have decreased by 7.5% from $1,956 to $1,809.47 (i.e., $1,486.56 + 12 HanesBrands shares × $25.99 + $11.03). This compares to a more modest 5% loss for investors who put the same $1,956 into a Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index fund during the same period.

Why did Sara Lee underperform the broader stock market indices during this period? Despite the cumulative buyback of more than $4 billion of its outstanding stock, Sara Lee’s fully diluted earnings per share dropped from $0.90 per share in 2005 to $0.52 per share in 2009. Furthermore, the book value per share, a proxy for the breakup or liquidation value of the firm, dropped from $3.28 in 2005 to $2.93 in 2009, reflecting the ongoing divestiture program. While the HanesBrands spin-off did create value for the shareholder, the amount was far too modest to offset the decline in Sara Lee’s market value. During the same period, total revenue grew at a tepid average annual rate of about 3% to about $13 billion in 2009.

-In what sense is the Sara Lee business strategy in effect a breakup strategy? Be specific.

Sara Lee Attempts to Create Value through Restructuring

After spurning a series of takeover offers, Sara Lee, a global consumer goods company, announced in early 2011 its intention to split the firm into two separate publicly traded companies. The two companies would consist of the firm’s North American retail and food service division and its international beverage business. The announcement comes after a long string of restructuring efforts designed to increase shareholder value. It remains to be seen if the latest effort will be any more successful than earlier efforts.

Reflecting a flawed business strategy, Sara Lee had struggled for more than a decade to create value for its shareholders by radically restructuring its portfolio of businesses. The firm’s business strategy had evolved from one designed in the mid-1980s to market a broad array of consumer products from baked goods to coffee to underwear under the highly recognizable brand name of Sara Lee into one that was designed to refocus the firm on the faster-growing food and beverage and apparel businesses. Despite acquiring several European manufacturers of processed meats in the early 1990s, the company’s profits and share price continued to flounder.

In September 1997, Sara Lee embarked on a major restructuring effort designed to boost both profits, which had been growing by about 6% during the previous five years, and the company’s lagging share price. The restructuring program was intended to reduce the firm’s degree of vertical integration, shifting from a manufacturing and sales orientation to one focused on marketing the firm’s top brands. The firm increasingly viewed itself as more of a marketing than a manufacturing enterprise.

Sara Lee outsourced or sold 110 manufacturing and distribution facilities over the next two years. Nearly 10,000 employees, representing 7% of the workforce, were laid off. The proceeds from the sale of facilities and the cost savings from outsourcing were either reinvested in the firm’s core food businesses or used to repurchase $3 billion in company stock. 1n 1999 and 2000, the firm acquired several brands in an effort to bolster its core coffee operations, including such names as Chock Full o’Nuts, Hills Bros, and Chase & Sanborn.

Despite these restructuring efforts, the firm’s stock price continued to drift lower. In an attempt to reverse the firm’s misfortunes, the firm announced an even more ambitious restructuring plan in 2000. Sara Lee would focus on three main areas: food and beverages, underwear, and household products. The restructuring efforts resulted in the shutdown of a number of meat packing plants and a number of small divestitures, resulting in a 10% reduction (about 13,000 people) in the firm’s workforce. Sara Lee also completed the largest acquisition in its history, purchasing The Earthgrains Company for $1.9 billion plus the assumption of $0.9 billion in debt. With annual revenue of $2.6 billion, Earthgrains specialized in fresh packaged bread and refrigerated dough. However, despite ongoing restructuring activities, Sara Lee continued to underperform the broader stock market indices.

In February 2005, Sara Lee executed its most ambitious plan to transform the firm into a company focused on the global food, beverage, and household and body care businesses. To this end, the firm announced plans to dispose of 40% of its revenues, totaling more than $8 billion, including its apparel, European packaged meats, U.S. retail coffee, and direct sales businesses.

In 2006, the firm announced that it had completed the sale of its branded apparel business in Europe, Global Body Care and European Detergents units, and its European meat processing operations. Furthermore, the firm spun off its U.S. Branded Apparel unit into a separate publicly traded firm called HanesBrands Inc. The firm raised more than $3.7 billion in cash from the divestitures. The firm was now focused on its core businesses: food, beverages, and household and body care.

In late 2008, Sara Lee announced that it would close its kosher meat processing business and sold its retail coffee business. In 2009, the firm sold its Household and Body Care business to Unilever for $1.6 billion and its hair care business to Procter & Gamble for $0.4 billion.

In 2010, the proceeds of the divestitures made the prior year were used to repurchase $1.3 billion of Sara Lee’s outstanding shares. The firm also announced its intention to repurchase another $3 billion of its shares during the next three years. If completed, this would amount to about one-third of its approximate $10 billion market capitalization at the end of 2010.

What remains of the firm are food brands in North America, including Hillshire Farm, Ball Park, and Jimmy Dean processed meats and Sara Lee baked goods and Earthgrains. A food distribution unit will also remain in North America, as will its beverage and bakery operations. Sara Lee is rapidly moving to become a food, beverage, and bakery firm. As it becomes more focused, it could become a takeover target.

Has the 2005 restructuring program worked? To answer this question, it is necessary to determine the percentage change in Sara Lee’s share price from the announcement date of the restructuring program to the end of 2010, as well as the percentage change in the share price of HanesBrands Inc., which was spun off on August 18, 2006. Sara Lee shareholders of record received one share of HanesBrands Inc. for every eight Sara Lee shares they held.

Sara Lee’s share price jumped by 6% on the February 21, 2004 announcement date, closing at $19.56. Six years later, the stock price ended 2010 at $14.90, an approximate 24% decline since the announcement of the restructuring program in early 2005. Immediately following the spinoff, HanesBrands’ stock traded at $22.06 per share; at the end of 2010, the stock traded at $25.99, a 17.8% increase.

A shareholder owning 100 Sara Lee shares when the spin-off was announced would have been entitled to 12.5 HanesBrands shares. However, they would have actually received 12 shares plus $11.03 for fractional shares (i.e., 0.5 × $22.06).

A shareholder of record who had 100 Sara Lee shares on the announcement date of the restructuring program and held their shares until the end of 2010 would have seen their investment decline 24% from $1,956 (100 shares × $19.56 per share) to $1,486.56 by the end of 2010. However, this would have been partially offset by the appreciation of the HanesBrands shares between 2006 and 2010. Therefore, the total value of the hypothetical shareholder’s investment would have decreased by 7.5% from $1,956 to $1,809.47 (i.e., $1,486.56 + 12 HanesBrands shares × $25.99 + $11.03). This compares to a more modest 5% loss for investors who put the same $1,956 into a Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index fund during the same period.

Why did Sara Lee underperform the broader stock market indices during this period? Despite the cumulative buyback of more than $4 billion of its outstanding stock, Sara Lee’s fully diluted earnings per share dropped from $0.90 per share in 2005 to $0.52 per share in 2009. Furthermore, the book value per share, a proxy for the breakup or liquidation value of the firm, dropped from $3.28 in 2005 to $2.93 in 2009, reflecting the ongoing divestiture program. While the HanesBrands spin-off did create value for the shareholder, the amount was far too modest to offset the decline in Sara Lee’s market value. During the same period, total revenue grew at a tepid average annual rate of about 3% to about $13 billion in 2009.

-In what sense is the Sara Lee business strategy in effect a breakup strategy? Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (33)

(33)

The Anatomy of a Reverse Morris Trust Transaction:

The Pringles Potato Chip Saga

Greater shareholder value may be created by exiting rather than operating a business.

Deal structures can impose significant limitations on a firm’s future strategies and tactics.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

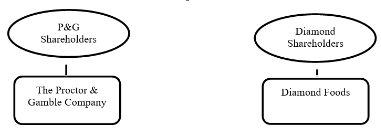

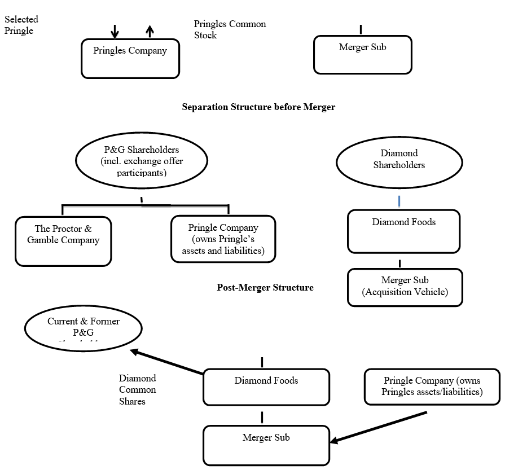

Following a rigorous portfolio review and an informal expression of interest in the Pringles brand by Diamond Foods (Diamond) in late 2009, Proctor & Gamble (P&G), the world’s leading manufacturer of household products, believed that Pringles could be worth more to its shareholders if divested than if retained. Pringles is the iconic potato chip brand, with sales in 140 countries and operations in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

Diamond’s executive management had long viewed the Pringles’ brand as an attractive fit for their strategy of building, acquiring, and energizing brands. The acquisition of Pringles would triple the size of the firm’s snack business and provide greater merchandising influence in the way in which its products are distributed. The merger would also give Diamond a substantial presence in Asia, Latin America, and Central Europe. The increased geographic diversity means the firm would derive almost one-half of its revenue from international sales.

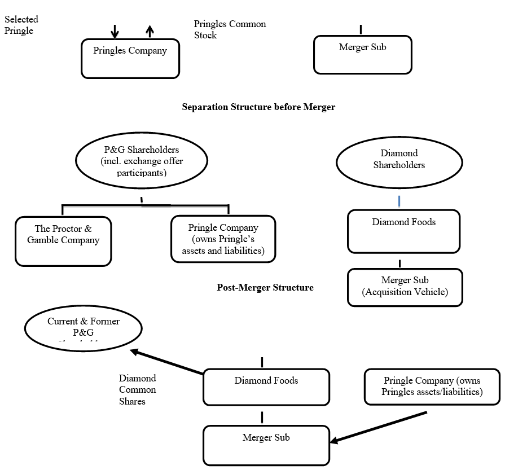

After extended negotiations, Diamond and P&G announced on April 15, 2011, their intent to merge P&G’s Pringles subsidiary into Diamond in a transaction valued at $2.35 billion. The purchase price consisted of $1.5 billion in Diamond common stock, valued at $51.47 per share, and Diamond’s assumption of $850 million in Pringles outstanding debt. The way in which the deal was structured enabled P&G shareholders to defer any gains they realize from the transaction and resulted in a one-time after-tax earnings increase for P&G of $1.5 billion due to the firm’s low tax basis in Pringles.

The offer to exchange Pringle shares for P&G shares reduced the number of outstanding P&G common shares, partially offsetting the impact on P&G’s earnings per share of the loss of Pringles earnings. Diamond agreed to issue one share of its common stock for each Pringles common share. The 29.1 million common shares issued by Diamond resulted in P&G shareholders’ participating in the exchange offer, owning a 57% stake in the combined firms, with Diamond’s shareholders owning the remainder.

The deal was structured as a reverse Morris Trust acquisition, which combines a divisive reorganization (e.g., a spin-off or a split-off) with an acquisitive reorganization (e.g., a statutory merger) to allow a tax-free transfer of a subsidiary under U.S. law. The use of a divisive reorganization results in the creation of a public company that is subsequently merged into a shell subsidiary (i.e., a privately owned company) of another firm, with the shell surviving.

The structure of the deal involved four discrete steps, outlined in separation and transaction agreements signed by P&G and Diamond. These steps included the following: (1) the creation by P&G of a wholly owned subsidiary containing Pringles’ assets and liabilities; (2) the recapitalization of the wholly owned Pringles subsidiary; (3) the separation of the wholly owned subsidiary through a split-off exchange offer; and (4) a merger with a wholly owned subsidiary of Diamond Foods. The separation agreement covered the first three steps, with the final step detailed in the transaction agreement.

Under the separation agreement, P&G contributed certain Pringles assets and liabilities to the Pringles Company, a newly formed wholly owned subsidiary of P&G. After P&G and Diamond reached a negotiated value for the Pringles Company equity of $1.5 billion, or $51.47 per share, the Pringles Company was subsequently recapitalized by issuing to P&G 29.1 million shares of Pringles Company stock. To complete the separation of Pringles from the parent firm, P&G distributed on the closing date Pringles shares to P&G shareholders participating in a share-exchange offer in which they agreed to exchange their P&G shares for Pringles shares.

In addition, the Pringles Company borrowed $850 million and used the proceeds to pay P&G a cash dividend and to acquire certain Pringles business assets held by P&G affiliates. Since P&G is the sole owner of the Pringles Company, the dividend is tax free to P&G because it is an intracompany transfer. If the exchange offer had not been fully subscribed, P&G would have distributed through a tax-free spin-off the remaining shares as a dividend to P&G shareholders.

The transaction agreement outlined the terms and conditions pertinent to completion of the merger with Diamond Foods. Immediately after the completion of the distribution, the Pringles Company merged with Merger Sub, a wholly owned shell subsidiary of Diamond, with Merger Sub’s continuing as the surviving company. The shares of Pringles Company common stock distributed in connection with the split-off exchange offer automatically converted into the right to receive shares of Diamond common stock on a one-for-one basis. After the merger, Diamond, through Merger Sub, owned and operated Pringles

Prior to the merger, Diamond already had formidable antitakeover defenses in place as part of its charter documents, including a classified board of directors, a prohibition against stockholders’ taking action by written consent (i.e., consent solicitation), and a requirement that stockholders give advance notice before raising matters at a stockholders’ meeting. Following the merger, Diamond adopted a shareholder-rights plan. The plan entitled the holder of such rights to purchase 1/100 of a share of Diamond’s Series A Junior Participating Preferred Stock if a person or group acquires 15% or more of Diamond’s outstanding common stock. Holders of this preferred stock (other than the person or group triggering their exercise) would be able to purchase Diamond common shares (flip-in poison pill) or those of any company into which Diamond is merged (flip-over poison pill) at a price of $60 per share. Such rights would expire in March 2015 unless extended by Diamond’s board of directors.

-Why was this transaction subject to the Morris Trust tax regulations?

Prior to the merger, Diamond already had formidable antitakeover defenses in place as part of its charter documents, including a classified board of directors, a prohibition against stockholders’ taking action by written consent (i.e., consent solicitation), and a requirement that stockholders give advance notice before raising matters at a stockholders’ meeting. Following the merger, Diamond adopted a shareholder-rights plan. The plan entitled the holder of such rights to purchase 1/100 of a share of Diamond’s Series A Junior Participating Preferred Stock if a person or group acquires 15% or more of Diamond’s outstanding common stock. Holders of this preferred stock (other than the person or group triggering their exercise) would be able to purchase Diamond common shares (flip-in poison pill) or those of any company into which Diamond is merged (flip-over poison pill) at a price of $60 per share. Such rights would expire in March 2015 unless extended by Diamond’s board of directors.

-Why was this transaction subject to the Morris Trust tax regulations?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (37)

(37)

The Anatomy of a Reverse Morris Trust Transaction:

The Pringles Potato Chip Saga

Greater shareholder value may be created by exiting rather than operating a business.

Deal structures can impose significant limitations on a firm’s future strategies and tactics.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Following a rigorous portfolio review and an informal expression of interest in the Pringles brand by Diamond Foods (Diamond) in late 2009, Proctor & Gamble (P&G), the world’s leading manufacturer of household products, believed that Pringles could be worth more to its shareholders if divested than if retained. Pringles is the iconic potato chip brand, with sales in 140 countries and operations in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

Diamond’s executive management had long viewed the Pringles’ brand as an attractive fit for their strategy of building, acquiring, and energizing brands. The acquisition of Pringles would triple the size of the firm’s snack business and provide greater merchandising influence in the way in which its products are distributed. The merger would also give Diamond a substantial presence in Asia, Latin America, and Central Europe. The increased geographic diversity means the firm would derive almost one-half of its revenue from international sales.

After extended negotiations, Diamond and P&G announced on April 15, 2011, their intent to merge P&G’s Pringles subsidiary into Diamond in a transaction valued at $2.35 billion. The purchase price consisted of $1.5 billion in Diamond common stock, valued at $51.47 per share, and Diamond’s assumption of $850 million in Pringles outstanding debt. The way in which the deal was structured enabled P&G shareholders to defer any gains they realize from the transaction and resulted in a one-time after-tax earnings increase for P&G of $1.5 billion due to the firm’s low tax basis in Pringles.

The offer to exchange Pringle shares for P&G shares reduced the number of outstanding P&G common shares, partially offsetting the impact on P&G’s earnings per share of the loss of Pringles earnings. Diamond agreed to issue one share of its common stock for each Pringles common share. The 29.1 million common shares issued by Diamond resulted in P&G shareholders’ participating in the exchange offer, owning a 57% stake in the combined firms, with Diamond’s shareholders owning the remainder.

The deal was structured as a reverse Morris Trust acquisition, which combines a divisive reorganization (e.g., a spin-off or a split-off) with an acquisitive reorganization (e.g., a statutory merger) to allow a tax-free transfer of a subsidiary under U.S. law. The use of a divisive reorganization results in the creation of a public company that is subsequently merged into a shell subsidiary (i.e., a privately owned company) of another firm, with the shell surviving.

The structure of the deal involved four discrete steps, outlined in separation and transaction agreements signed by P&G and Diamond. These steps included the following: (1) the creation by P&G of a wholly owned subsidiary containing Pringles’ assets and liabilities; (2) the recapitalization of the wholly owned Pringles subsidiary; (3) the separation of the wholly owned subsidiary through a split-off exchange offer; and (4) a merger with a wholly owned subsidiary of Diamond Foods. The separation agreement covered the first three steps, with the final step detailed in the transaction agreement.

Under the separation agreement, P&G contributed certain Pringles assets and liabilities to the Pringles Company, a newly formed wholly owned subsidiary of P&G. After P&G and Diamond reached a negotiated value for the Pringles Company equity of $1.5 billion, or $51.47 per share, the Pringles Company was subsequently recapitalized by issuing to P&G 29.1 million shares of Pringles Company stock. To complete the separation of Pringles from the parent firm, P&G distributed on the closing date Pringles shares to P&G shareholders participating in a share-exchange offer in which they agreed to exchange their P&G shares for Pringles shares.

In addition, the Pringles Company borrowed $850 million and used the proceeds to pay P&G a cash dividend and to acquire certain Pringles business assets held by P&G affiliates. Since P&G is the sole owner of the Pringles Company, the dividend is tax free to P&G because it is an intracompany transfer. If the exchange offer had not been fully subscribed, P&G would have distributed through a tax-free spin-off the remaining shares as a dividend to P&G shareholders.

The transaction agreement outlined the terms and conditions pertinent to completion of the merger with Diamond Foods. Immediately after the completion of the distribution, the Pringles Company merged with Merger Sub, a wholly owned shell subsidiary of Diamond, with Merger Sub’s continuing as the surviving company. The shares of Pringles Company common stock distributed in connection with the split-off exchange offer automatically converted into the right to receive shares of Diamond common stock on a one-for-one basis. After the merger, Diamond, through Merger Sub, owned and operated Pringles

Prior to the merger, Diamond already had formidable antitakeover defenses in place as part of its charter documents, including a classified board of directors, a prohibition against stockholders’ taking action by written consent (i.e., consent solicitation), and a requirement that stockholders give advance notice before raising matters at a stockholders’ meeting. Following the merger, Diamond adopted a shareholder-rights plan. The plan entitled the holder of such rights to purchase 1/100 of a share of Diamond’s Series A Junior Participating Preferred Stock if a person or group acquires 15% or more of Diamond’s outstanding common stock. Holders of this preferred stock (other than the person or group triggering their exercise) would be able to purchase Diamond common shares (flip-in poison pill) or those of any company into which Diamond is merged (flip-over poison pill) at a price of $60 per share. Such rights would expire in March 2015 unless extended by Diamond’s board of directors.

-Speculate as to why P&G chose to split-off rather than spin-off Pringles as part its plan to merge Post with Ralcorp. Be specific.

Prior to the merger, Diamond already had formidable antitakeover defenses in place as part of its charter documents, including a classified board of directors, a prohibition against stockholders’ taking action by written consent (i.e., consent solicitation), and a requirement that stockholders give advance notice before raising matters at a stockholders’ meeting. Following the merger, Diamond adopted a shareholder-rights plan. The plan entitled the holder of such rights to purchase 1/100 of a share of Diamond’s Series A Junior Participating Preferred Stock if a person or group acquires 15% or more of Diamond’s outstanding common stock. Holders of this preferred stock (other than the person or group triggering their exercise) would be able to purchase Diamond common shares (flip-in poison pill) or those of any company into which Diamond is merged (flip-over poison pill) at a price of $60 per share. Such rights would expire in March 2015 unless extended by Diamond’s board of directors.

-Speculate as to why P&G chose to split-off rather than spin-off Pringles as part its plan to merge Post with Ralcorp. Be specific.

(Essay)

4.9/5  (30)

(30)

Hughes Corporation's Dramatic Transformation

In one of the most dramatic redirections of corporate strategy in U.S. history, Hughes Corporation transformed itself from a defense industry behemoth into the world's largest digital information and communications company. Once California's largest manufacturing employer, Hughes Corporation built spacecraft, the world's first working laser, communications satellites, radar systems, and military weapons systems. However, by the late 1990s, the firm had undergone substantial gut-wrenching change to reposition the firm in what was viewed as a more attractive growth opportunity. This transformation culminated in the firm being acquired in 2004 by News Corp., a global media empire.

To accomplish this transformation, Hughes divested its communications satellite businesses and its auto electronics operation. The corporate overhaul created a firm focused on direct-to-home satellite broadcasting with its DirecTV service offering. DirecTV's introduction to nearly 12 million U.S. homes was a technology made possible by U.S. military spending during the early 1980s. Although military spending had fueled much of Hughes' growth during the decade of the 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear by 1988 that the level of defense spending of the Reagan years was coming to a close with the winding down of the cold war.

For the next several years, Hughes attempted to find profitable niches in the rapidly consolidating U.S. defense contracting industry. Hughes acquired General Dynamics' missile business and made 15 smaller defense-related acquisitions. Eventually, Hughes' parent firm, General Motors, lost enthusiasm for additional investment in defense-related businesses. GM decided that, if Hughes could not participate in the shrinking defense industry, there was no reason to retain any interests in the industry at all. In November 1995, Hughes initiated discussions with Raytheon, and two years later, it sold its aerospace and defense business to Raytheon for $9.8 billion. The firm also merged its Delco product line with GM's Delphi automotive systems. What remained was the firm's telecommunications division. Hughes had transformed itself from a $16 billion defense contractor to a svelte $4 billion telecommunications business.

Hughes' telecommunications unit was its smallest operation but, with DirecTV, its fastest growing. The transformation was to exact a huge cultural toll on Hughes' employees, most of whom had spent their careers dealing with the U.S. Department of Defense. Hughes moved to hire people aggressively from the cable and broadcast businesses. By the late 1990s, former Hughes' employees constituted only 15-20 percent of DirecTV's total employees.

Restructuring continued through the end of the 1990s. In 2000, Hughes sold its satellite manufacturing operations to Boeing for $3.75 billion. This eliminated the last component of the old Hughes and cut its workforce in half. In December 2000, Hughes paid about $180 million for Telocity, a firm that provides digital subscriber line service through phone lines. This acquisition allowed Hughes to provide high-speed Internet connections through its existing satellite service, mainly in more remote rural areas, as well as phone lines targeted at city dwellers. Hughes now could market the same combination of high-speed Internet services and video offered by cable providers, Hughes' primary competitor.

In need of cash, GM put Hughes up for sale in late 2000, expressing confidence that there would be a flood of lucrative offers. However, the faltering economy and stock market resulted in GM receiving only one serious bid, from media tycoon Rupert Murdoch of News Corp. in February 2001. But, internal discord within Hughes and GM over the possible buyer of Hughes Electronics caused GM to backpedal and seek alternative bidders. In late October 2001, GM agreed to sell its Hughes Electronics subsidiary and its DirecTV home satellite network to EchoStar Communication for $25.8 billion. However, regulators concerned about the antitrust implications of the deal disallowed this transaction. In early 2004, News Corp., General Motors, and Hughes reached a definitive agreement in which News Corp acquired GM's 19.9 percent stake in Hughes and an additional 14.1 percent of Hughes from public shareholders and GM's pension and other benefit plans. News Corp. paid about $14 per share, making the deal worth about $6.6 billion for 34.1 percent of Hughes. The implied value of 100 percent of Hughes was, at that time, $19.4 billion, about three fourths of EchoStar's valuation three years earlier.

-Speculate as to why News Corp, a major entertainment industry content provider, might have been interested in acquiring Hughes. Be specific.

(Essay)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

An equity carve-out by a parent of one of its subsidiaries is often a precursor to a

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (42)

(42)

Hughes Corporation's Dramatic Transformation

In one of the most dramatic redirections of corporate strategy in U.S. history, Hughes Corporation transformed itself from a defense industry behemoth into the world's largest digital information and communications company. Once California's largest manufacturing employer, Hughes Corporation built spacecraft, the world's first working laser, communications satellites, radar systems, and military weapons systems. However, by the late 1990s, the firm had undergone substantial gut-wrenching change to reposition the firm in what was viewed as a more attractive growth opportunity. This transformation culminated in the firm being acquired in 2004 by News Corp., a global media empire.

To accomplish this transformation, Hughes divested its communications satellite businesses and its auto electronics operation. The corporate overhaul created a firm focused on direct-to-home satellite broadcasting with its DirecTV service offering. DirecTV's introduction to nearly 12 million U.S. homes was a technology made possible by U.S. military spending during the early 1980s. Although military spending had fueled much of Hughes' growth during the decade of the 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear by 1988 that the level of defense spending of the Reagan years was coming to a close with the winding down of the cold war.

For the next several years, Hughes attempted to find profitable niches in the rapidly consolidating U.S. defense contracting industry. Hughes acquired General Dynamics' missile business and made 15 smaller defense-related acquisitions. Eventually, Hughes' parent firm, General Motors, lost enthusiasm for additional investment in defense-related businesses. GM decided that, if Hughes could not participate in the shrinking defense industry, there was no reason to retain any interests in the industry at all. In November 1995, Hughes initiated discussions with Raytheon, and two years later, it sold its aerospace and defense business to Raytheon for $9.8 billion. The firm also merged its Delco product line with GM's Delphi automotive systems. What remained was the firm's telecommunications division. Hughes had transformed itself from a $16 billion defense contractor to a svelte $4 billion telecommunications business.

Hughes' telecommunications unit was its smallest operation but, with DirecTV, its fastest growing. The transformation was to exact a huge cultural toll on Hughes' employees, most of whom had spent their careers dealing with the U.S. Department of Defense. Hughes moved to hire people aggressively from the cable and broadcast businesses. By the late 1990s, former Hughes' employees constituted only 15-20 percent of DirecTV's total employees.

Restructuring continued through the end of the 1990s. In 2000, Hughes sold its satellite manufacturing operations to Boeing for $3.75 billion. This eliminated the last component of the old Hughes and cut its workforce in half. In December 2000, Hughes paid about $180 million for Telocity, a firm that provides digital subscriber line service through phone lines. This acquisition allowed Hughes to provide high-speed Internet connections through its existing satellite service, mainly in more remote rural areas, as well as phone lines targeted at city dwellers. Hughes now could market the same combination of high-speed Internet services and video offered by cable providers, Hughes' primary competitor.

In need of cash, GM put Hughes up for sale in late 2000, expressing confidence that there would be a flood of lucrative offers. However, the faltering economy and stock market resulted in GM receiving only one serious bid, from media tycoon Rupert Murdoch of News Corp. in February 2001. But, internal discord within Hughes and GM over the possible buyer of Hughes Electronics caused GM to backpedal and seek alternative bidders. In late October 2001, GM agreed to sell its Hughes Electronics subsidiary and its DirecTV home satellite network to EchoStar Communication for $25.8 billion. However, regulators concerned about the antitrust implications of the deal disallowed this transaction. In early 2004, News Corp., General Motors, and Hughes reached a definitive agreement in which News Corp acquired GM's 19.9 percent stake in Hughes and an additional 14.1 percent of Hughes from public shareholders and GM's pension and other benefit plans. News Corp. paid about $14 per share, making the deal worth about $6.6 billion for 34.1 percent of Hughes. The implied value of 100 percent of Hughes was, at that time, $19.4 billion, about three fourths of EchoStar's valuation three years earlier.

-Why did Hughes move so aggressively to hire employees from the cable TV and broadcast industry?

(Essay)

4.9/5  (32)

(32)

Which of the following is generally considered a motive for exiting businesses?

(Multiple Choice)

4.8/5  (34)

(34)

AT&T (1984 - 2005)-A POSTER CHILD

FOR RESTRUCTURING GONE AWRY

Between 1984 and 2000, AT&T underwent four major restructuring programs. These included the government-mandated breakup in 1984, the 1996 effort to eliminate customer conflicts, the 1998 plan to become a broadband powerhouse, and the most recent restructuring program announced in 2000 to correct past mistakes. It is difficult to identify another major corporation that has undergone as much sustained trauma as AT&T. Ironically, a former AT&T operating unit acquired its former parent in 2005.

The 1984 Restructure: Changed the Organization But Not the Culture

The genesis of Ma Bell's problems may have begun with the consent decree signed with the Department of Justice in 1984, which resulted in the spin-off of its local telephone operations to its shareholders. AT&T retained its long-distance and telecommunications equipment manufacturing operations. Although the breadth of the firm's product offering changed dramatically, little else seems to have changed. The firm remained highly bureaucratic, risk averse, and inward looking. However, substantial market share in the lucrative long-distance market continued to generate huge cash flow for the company, thereby enabling the company to be slow to react to the changing competitive dynamics of the marketplace.

The 1996 Restructure: Lack of a Coherent Strategy

Cash accumulated from the long-distance business was spent on a variety of ill-conceived strategies such as the firm's foray into the personal computer business. After years of unsuccessfully attempting to redefine the company's strategy, AT&T once again resorted to a major restructure of the firm. In 1996, AT&T spun-off Lucent Technologies (its telecommunications equipment business) and NCR (a computer services business) to shareholders to facilitate Lucent equipment sales to former AT&T operations and to eliminate the non-core NCR computer business. However, this had little impact on the AT&T share price.

The 1998 Restructure: Vision Exceeds Ability to Execute

In its third major restructure since 1984, AT&T CEO Michael Armstrong passionately unveiled in June of 1998 a daring strategy to transform AT&T from a struggling long-distance telephone company into a broadband internet access and local phone services company. To accomplish this end, he outlined his intentions to acquire cable companies MediaOne Group and Telecommunications Inc. for $58 billion and $48 billion, respectively. The plan was to use cable-TV networks to deliver the first fully integrated package of broadband internet access and local phone service via the cable-TV network.

AT&T Could Not Handle Its Early Success

During the next several years, Armstrong seemed to be up to the task, cutting sales, general, and administrative expense's share of revenue from 28 percent to 20 percent, giving AT&T a cost structure comparable to its competitors. He attempted to change the bureaucratic culture to one able to compete effectively in the deregulated environment of the post-1996 Telecommunications Act by issuing stock options to all employees, tying compensation to performance, and reducing layers of managers. He used AT&T's stock, as well as cash, to buy the cable companies before the decline in AT&T's long-distance business pushed the stock into a free fall. He also transformed AT&T Wireless from a collection of local businesses into a national business.

Notwithstanding these achievements, AT&T experienced major missteps. Employee turnover became a big problem, especially among senior managers. Armstrong also bought Telecommunications and MediaOne when valuations for cable-television assets were near their peak. He paid about $106 billion in 2000, when they were worth about $80 billion. His failure to cut enough deals with other cable operators (e.g., Time Warner) to sell AT&T's local phone service meant that AT&T could market its services only in regional markets rather than on a national basis. In addition, AT&T moved large corporate customers to its Concert joint venture with British Telecom, alienating many AT&T salespeople, who subsequently quit. As a result, customer service deteriorated rapidly and major customers defected. Finally, Armstrong seriously underestimated the pace of erosion in AT&T's long-distance revenue base.

AT&T May Have Become Overwhelmed by the Rate of Change

What happened? Perhaps AT&T fell victim to the same problems many other acquisitive companies have. AT&T is a company capable of exceptional vision but incapable of effective execution. Effective execution involves buying or building assets at a reasonable cost. Its substantial overpayment for its cable acquisitions meant that it would be unable to earn the returns required by investors in what they would consider a reasonable period. Moreover, Armstrong's efforts to shift from the firm's historical business by buying into the cable-TV business through acquisition had saddled the firm with $62 billion in debt.

AT&T tried to do too much too quickly. New initiatives such as high-speed internet access and local telephone services over cable-television network were too small to pick up the slack. Much time and energy seems to have gone into planning and acquiring what were viewed as key building blocks to the strategy. However, there appears to have been insufficient focus and realism in terms of the time and resources required to make all the pieces of the strategy fit together. Some parts of the overall strategy were at odds with other parts. For example, AT&T undercut its core long-distance wired telephone business by offers of free long-distance wireless to attract new subscribers. Despite aggressive efforts to change the culture, AT&T continued to suffer from a culture that evolved in the years before 1996 during which the industry was heavily regulated. That atmosphere bred a culture based on consensus building, ponderously slow decision-making, and a low tolerance for risk. Consequently, the AT&T culture was unprepared for the fiercely competitive deregulated environment of the late 1990s (Truitt, 2001).

Furthermore, AT&T created individual tracking stocks for AT&T Wireless and for Liberty Media. The intention of the tracking stocks was to link the unit's stock to its individual performance, create a currency for the unit to make acquisitions, and to provide a new means of motivating the unit's management by giving them stock in their own operation. Unlike a spin-off, AT&T's board continued to exert direct control over these units. In an IPO in April 2000, AT&T sold 14 percent of AT&T's Wireless tracking stock to the public to raise funds and to focus investor attention on the true value of the Wireless operations.

Investors Lose Patience

Although all of these actions created a sense that grandiose change was imminent, investor patience was wearing thin. Profitability foundered. The market share loss in its long-distance business accelerated. Although cash flow remained strong, it was clear that a cash machine so dependent on the deteriorating long-distance telephone business soon could grind to a halt. Investors' loss of faith was manifested in the sharp decline in AT&T stock that occurred in 2000.

The 2000 Restructure: Correcting the Mistakes of the Past

Pushed by investor impatience and a growing realization that achieving AT&T's vision would be more time and resource consuming than originally believed, Armstrong announced on October 25, 2000 the breakup of the business for the fourth time. The plan involved the creation of four new independent companies including AT&T Wireless, AT&T Consumer, AT&T Broadband, and Liberty Media.

By breaking the company into specific segments, AT&T believed that individual units could operate more efficiently and aggressively. AT&T's consumer long-distance business would be able to enter the digital subscriber line (DSL) market. DSL is a broadband technology based on the telephone wires that connect individual homes with the telephone network. AT&T's cable operations could continue to sell their own fast internet connections and compete directly against AT&T's long-distance telephone business. Moreover, the four individual businesses would create "pure-play" investor opportunities. Specifically, AT&T proposed splitting off in early 2001 AT&T Wireless and issuing tracking stocks to the public in late 2001 for AT&T's Consumer operations, including long-distance and Worldnet Internet service, and AT&T's Broadband (cable) operations. The tracking shares would later be converted to regular AT&T common shares as if issued by AT&T Broadband, making it an independent entity. AT&T would retain AT&T Business Services (i.e., AT&T Lab and Telecommunications Network) with the surviving AT&T entity. Investor reaction was swift and negative. Not swayed by the proposal, investors caused the stock to drop 13 percent in a single day. Moreover, it ended 2000 at 17 ½, down 66 percent from the beginning of the year.

The More Things Change The More They Stay The Same

On July 10, 2001, AT&T Wireless Services became an independent company, in accordance with plans announced during the 2000 restructure program. AT&T Wireless became a separate company when AT&T converted the tracking shares of the mobile-phone business into common stock and split-off the unit from the parent. AT&T encouraged shareholders to exchange their AT&T common shares for Wireless common shares by offering AT&T shareholders 1.176 Wireless shares for each share of AT&T common. The exchange ratio represented a 6.5 percent premium over AT&T's current common share price. AT&T Wireless shares have fallen 44 percent since AT&T first sold the tracking stock in April 2000. On August 10, 2001, AT&T spun off Liberty Media.

After extended discussions, AT&T agreed on December 21, 2001 to merge its broadband unit with Comcast to create the largest cable television and high-speed internet service company in the United States. Without the future growth engine offered by Broadband and Wireless, AT&T's remaining long-distance businesses and business services operations had limited growth prospects. After a decade of tumultuous change, AT&T was back where it was at the beginning of the 1990s. At about $15 billion in late 2004, AT&T's market capitalization was about one-sixth of that of such major competitors as Verizon and SBC. SBC Communications (a former local AT&T operating company) acquired AT&T on November 18, 2005 in a $16 billion deal and promptly renamed the combined firms AT&T.

-Why do you believe that AT&T chose to split-off its wireless operations rather than to divest the unit? What might you have done differently?

(Essay)

4.8/5  (32)

(32)

Showing 101 - 120 of 152

Filters

- Essay(0)

- Multiple Choice(0)

- Short Answer(0)

- True False(0)

- Matching(0)